When it comes to optimising metabolic health and blood sugar management, there are many similarities between how to approach Type-1 Diabetes, Type-2 Diabetes, or other conditions related to poor metabolic health.

Because people with Type-1 Diabetes must constantly measure and actively manage their blood glucose and insulin, we can learn a lot from how their bodies respond to the food they eat.

Recently, many people have asked for tips on how to optimise their Type-1 Diabetes management. So, I created this guide to unpack how we do it as a family with two people living with T1D. This approach has helped my wife Monica and my 16-year-old son optimise their nutrition, insulin and blood glucose to thrive with Type-1 Diabetes.

This article includes:

- a high-level overview of Type-1 Diabetes,

- learnings from my family’s experience and

- the best way to optimise your blood glucose and insulin management.

If you or a loved one are managing Type-1 Diabetes, this information may be especially useful to you. But even if you are part of the 99.95% of the population blessed with a functioning pancreas, this information will be valuable to help you improve your metabolic health.

- What Is Type-1 Diabetes?

- What Causes Type-1 Diabetes?

- Is Diabetes Type-1 Diabetes Genetic or Hereditary?

- When Does Type-1 Diabetes Occur?

- What is Latent Autoimmune Diabetes (LADA)

- How is Type-1 Diabetes Diagnosed?

- How Prevalent is Type-1 Diabetes?

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis vs Nutritional Ketosis

- Our Son’s Type-1 Diagnosis

- What is the Difference Between Type-1 Diabetes and Type-2 Diabetes?

- Insulin Resistance and Double Diabetes

- What Are the Risks of Type-1 Diabetes?

- Life Expectancy of People with Type 1 Diabetes

- The Upsides of Type-1 Diabetes

- What Are Normal Healthy Blood Glucose Levels?

- Dr Bernstein’s Law of Small Numbers

- Injected Insulin is Different

- What Happens When Blood Glucose Rises Too High?

- What are the Risks of Running Blood Glucose Too Low?

- What Happens to Glucose and Insulin Levels After Eating?

- What Is the Difference Between Bolus vs Basal Insulin?

- Factors that Impact Total Insulin Requirement

- Energy Toxicity is The Root Cause of Insulin Toxicity

- Insulin Dosing for People with Type-1 Diabetes

- How to Optimise Basal Insulin

- Technology for Type-1 Diabetes Management

- How Does the Menstrual Cycle Affect Type-1 Diabetes?

- Is a Low-Carb or Low-Fat Diet Optimal for Type 1 Diabetes Management?

- How to Not Lose Your Mind

- What Are the Best Foods for Type-1 Diabetics to Eat?

- Summary

- More

What Is Type-1 Diabetes?

Type-1 Diabetes is a chronic condition where the pancreas produces little or no insulin.

What Causes Type-1 Diabetes?

A healthy and regulated immune system fights off antigens that the body recognises as foreign. However, sometimes the body is prone to a misguided immune response where it cannot distinguish itself from an antigen. This is known as ‘autoimmunity’ where the body attacks a part of itself.

If this misdirected autoimmune reaction is directed towards the pancreas, it can destroy pancreatic beta cells that produce insulin. This autoimmune process can go on for months or years before symptoms appear, and you are eventually diagnosed with Type-1 Diabetes.

Is Diabetes Type-1 Diabetes Genetic or Hereditary?

Type-1 Diabetes usually has a genetic component, and children whose parents have Type-1 Diabetes or another autoimmune condition(s) are more likely to be diagnosed with it.

Most Caucasians with Type-1 Diabetes have the HLA-DR3 or HLA-DR4 genes, which are both linked to autoimmune tendencies and conditions.

If you’re interested in learning if your child is at risk of developing T1D, an antibody test can be done for children who have siblings with Type-1 Diabetes to measure the antibodies they have to insulin or to an enzyme called glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). High GAD antibodies indicate that a child has a higher risk of developing T1D.

While there is no surefire way to reverse the autoimmune attack on the pancreas, it can be slowed. Early detection of Type-1 Diabetes enables early intervention with insulin and dietary modification that can reduce the burden on the pancreas so beta cell function can be preserved for longer.

When Does Type-1 Diabetes Occur?

Type-1 Diabetes is usually diagnosed in adolescence and during periods of rapid growth when the body’s demand for insulin is higher. According to the CDC, Type-1 Diabetes is most often diagnosed between ages 13 and 14. However, a T1D diagnosis can occur at any age.

What is Latent Autoimmune Diabetes (LADA)

Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults (LADA) is a slower progressing form of autoimmune diabetes that occurs in older people.

Because it happens later in life, LADA is often mistaken for Type-2 Diabetes but can be diagnosed by confirming low insulin production, low C-peptide, and elevated blood glucose.

Starting insulin therapy and dietary modification sooner rather than later can give the beta cells in the pancreas a break, slow the autoimmune destruction and hence extend insulin production.

While LADA and Type-1 Diabetes are both autoimmune conditions primarily influenced by genetics, it appears that the autoimmune response is accelerated if the pancreas is constantly stressed (e.g., due to rapid growth, obesity or a high glycemic diet).

How is Type-1 Diabetes Diagnosed?

Type 1 Diabetes is often diagnosed based on symptoms and bloodwork. Symptoms of Type-1 Diabetes can include:

- excessive thirst and urination as the body attempts to flush the excess glucose it cannot process from the system;

- extreme hunger as the body cannot utilise carbohydrates;

- unexplained weight loss due to low insulin that prompts the body to release stored energy rapidly;

- feeling tired and weak as the body cannot use energy from food; and

- blurry vision, spaciness, irritability, and fatigue from uncontrolled blood glucose levels.

How Prevalent is Type-1 Diabetes?

According to Prevalence and incidence of type-1 diabetes in the world: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 15 in 100,000 (or 0.015%) have Type-1 Diabetes.

A recent paper in the Lancet, there were approximately 8.4 million people in 2021 living with Type-1 Diabetes worldwide. However, this number is predicted to increase 60 to 107% by 2040.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis vs Nutritional Ketosis

Insulin helps the body keep stored energy locked away. Without insulin, energy is free to float around the bloodstream. Because of insufficient insulin, excessive amounts of glucose, ketones, and free fatty acids are released into the blood in the instance of T1D. Hence, many people experience diabetic ketoacidosis when they are in the process of being diagnosed with Type-1 Diabetes.

While many people fear the process of ketosis due to its association with diabetic ketoacidosis, it is a normal and healthy occurrence for people who consume fewer carbohydrates. For reference:

- Someone in ‘nutritional ketosis’ will see lower blood glucose levels alongside ketones up to 0.6 mmol/L.

- In contrast, someone in diabetic ketoacidosis will see significantly elevated blood sugars (e.g., >200 mg/dL, or 11.1 mmol/L) and high blood ketone values above 3.0 mmol/L.

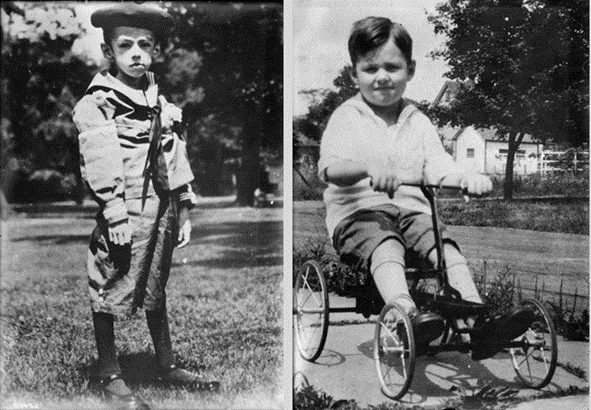

Without insulin treatment, diabetic ketoacidosis can be very dangerous and cause rapid fat and muscle loss. Fortunately, Frederick Banting and Charles Best discovered how to isolate the hormone insulin over a century ago so it could be injected into people with Type-1 Diabetes. As a result, someone diagnosed with untreated T1D can quickly regain precious fat and muscle.

To put into perspective how important insulin is, the photo below shows the same child before and after insulin therapy. Today, while often expensive, insulin is readily available and can be administered as soon as Type 1 Diabetes is diagnosed.

Our Son’s Type-1 Diagnosis

In late 2021, our son Mike was eating a LOT more than usual, and his carb cravings were high. He is super active, plays rugby, and trains in the gym regularly. He was getting lean, but we chalked it up to his high activity levels.

In hindsight, we now realise the muscle cramps he was experiencing may have been early warning signs of low insulin, as this can trigger sodium loss. But because he had made it to 16 without developing T1D, we didn’t suspect it.

But one day, he wanted to check his blood sugar after some heavy squats. It was 23.3 mmol/L (420 mg/dL)! We checked his blood and urine ketones, which were normal; he was not in ketoacidosis.

The following day I took him to the doctor to get his insulin, c-peptide, and HbA1c tested.

The tests confirm what we feared: Type-1 Diabetes.

His HbA1c came back at 14.5%! For reference, 6.5% is considered diabetic, and <5.7% is normal.

Additionally, his insulin and C-peptide test showed that his pancreas was producing a minimal amount of insulin; C-peptide is made in the pancreas along with insulin. Therefore, concurrent low insulin levels and low C-peptide confirm that the pancreas is producing inadequate insulin.

Later that day, we headed off to the hospital, and he started insulin.

The photo on the left shows him in the hospital with his JDRF bear, Rufus, that they give every ‘child’ at diagnosis in the paediatric hospital. He had gotten down to 77 kg on the day of diagnosis.

The photo on the right shows him after he competed in his first powerlifting competition, only five weeks after starting insulin. In that short period, he’d gained 13 kg and added 40kg to his deadlift! Only a year after diagnosis, he’s running an HbA1c of 5.2 – 5.6%.

He’s now training to hit an under-18 deadlift world record in December to celebrate his one-year diaversary.

What is the Difference Between Type-1 Diabetes and Type-2 Diabetes?

People with Type-1 and Type-2 both have inadequate insulin to maintain normal blood glucose levels.

People with Type-1 Diabetes cannot make enough insulin. Meanwhile, people with T2D produce insulin, but their cells are no longer sensitive to it.

People with both types of diabetes cannot maintain blood glucose levels in the normal healthy range without medications like insulin.

People with Type-2 Diabetes often accumulate their condition after years of metabolic assault with processed foods, poor lifestyle choices, and lack of movement.

Although these people still produce insulin, it’s not enough to keep their excess stored energy from overflowing into their bloodstream. People with T2D often require hundreds of units of injected (exogenous) insulin to control their blood glucose levels on top of the insulin their pancreas produces.

In contrast, someone with Type-1 Diabetes often does not have control over whether they will end up with T1D or when it will happen. For example, someone with well-controlled Type-1 Diabetes with healthy body fat levels may only require 15-50 daily insulin units to keep their blood glucose levels in the optimal range.

Insulin Resistance and Double Diabetes

Because someone with T2D’s pancreas has to produce substantial amounts of insulin constantly, they can experience ‘pancreatic burnout’.

Conversely, people with Type-1 Diabetes can also become insulin resistant from accumulating excess body fat if they inject insulin to manage their standard western diet. Both occurrences are commonly referred to as ‘Double Diabetes’.

Hence, it is crucial for people with either form of diabetes to work to achieve more optimal body composition and metabolic health. For more details, see

- What Is Insulin Resistance (and How to Reverse It)?

- The Real Reason You’re Insulin Resistant and The Macros to Reverse It, and

- Personal Fat Threshold Model of Insulin Resistance, Diabetes and Obesity vs the Carbohydrate Insulin Model.

What Are the Risks of Type-1 Diabetes?

The risks and complications of Type-1 and Type-2 diabetes are similar. However, because people with Type-1 tend to have much higher blood glucose levels, those associated with T1D tend to be more extreme. These include:

- heart and blood vessel disease,

- nerve damage (neuropathy),

- kidney damage (nephropathy),

- eye damage (retinopathy),

- foot damage,

- chronic infection and resulting loss of limbs,

- skin and mouth conditions, and

- pregnancy complications.

Shortly after we married, my wife Monica and I started thinking about having kids. It was the pregnancy complications that motivated us to improve her Type-1 Diabetes management to try to get off the glucose-insulin rollercoaster.

Life Expectancy of People with Type 1 Diabetes

A recent paper in the Lancet showed that people with Type 1 Diabetes have a reduced life expectancy of 24 years. In high-income countries with better access to insulin and health care, this differential is only 11 years. However, in low-income counties, this differential is a massive 47 years!

The good news is that this differential can be reduced significantly if someone uses diet and lifestyle changes to keep their blood sugars in the normal healthy range.

When my wife was diagnosed at 10, they told her family that her quality of life would decrease dramatically after 30, and she may live to 40. Instead, now at 46, she’s thriving and has beaten those odds!

The Upsides of Type-1 Diabetes

Although it’s a serious condition, Type-1 Diabetes isn’t a death sentence.

Because it can motivate someone to take their health and nutrition seriously, many people with Type-1 Diabetes are often significantly healthier than the general population.

One notable example is 27-year-old T1D Jessica Buettner, a recent IPF powerlifting championship gold medallist in the 72 kg class. Her mother taught her how to manage her nutrition at a young age to help manage her diabetes.

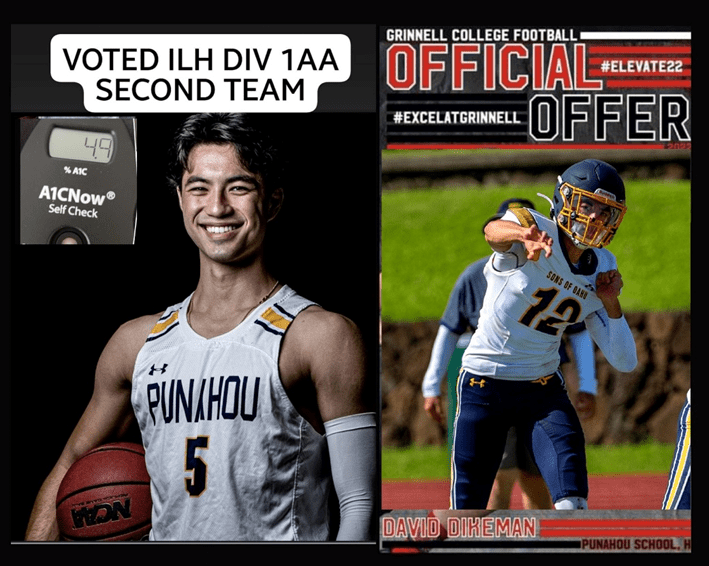

Another inspirational example is Dave Dikeman, a mentoree of Dr Richard Bernstein.

Dave’s father, RD Dikeman, is one of the Type 1 Grit Facebook Group founders. He has inspired and influenced our family in many ways. You can see my interview with RD here.

Dave himself recently shared an excellent overview explaining how he manages his T1D.

Another notable example is engineer-turned-doctor Richard K Bernstein. After being diagnosed with T1D at age 12, left engineering to study medicine in the hopes of progressing T1D treatment. He still helps people optimise their diabetes at the young age of 88!

Bernstein got his hands on an early blood sugar meter (shown below) and started testing his blood glucose to understand how different foods affected his blood glucose.

Modern insulin pumps now use Bernstein’s calculations based on his learnings and understanding from quantifying his own blood glucose to compute users’ basal (insulin in between meals) and bolus (insulin taken with food).

His lower-carbohydrate, protein-focussed approach has also helped thousands of T1Ds regain control over their blood glucose.

Bernstein and the Dikemans created Dr Bernstein’s Diabetes University YouTube Channel to share Dr B’s wisdom and insights on normalising blood sugars and thriving with Type-1 Diabetes.

What Are Normal Healthy Blood Glucose Levels?

Several markers are used to evaluate metabolic in the medical world, like Hb1Ac and fasting blood glucose. HbA1c measures someone’s average blood glucose over the past three months.

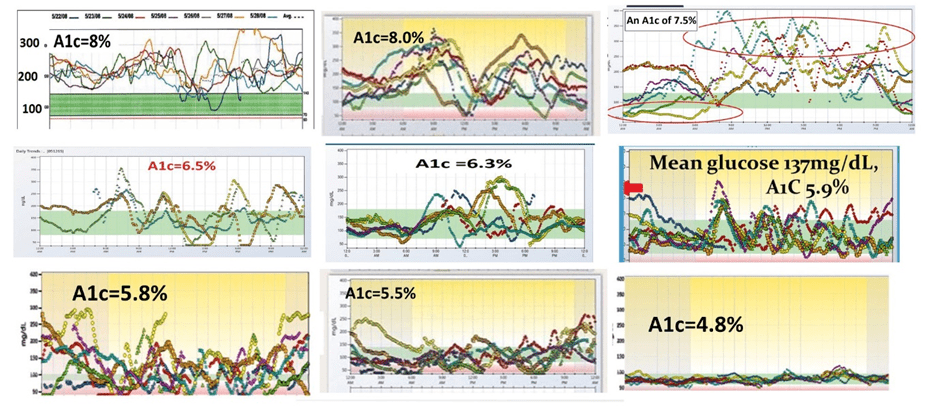

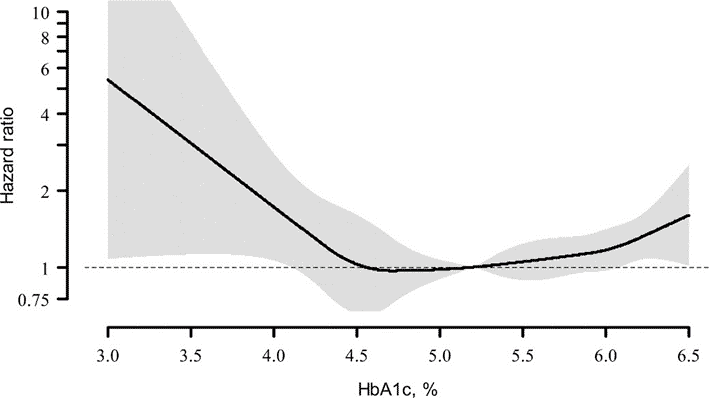

Although people with Type-1 Diabetes are encouraged to keep their Hb1Ac below 7.0%, this is still considered well into the diabetic range. As we can see from the chart below taken from this paper discussing Hb1Ac and cardiovascular risk, the overall hazard ratio rises once HbA1c is above 6.0%. A more optimal Hb1Ac is between 4.5 and 5.4%.

We’ve included the table below to show the generally accepted ‘normal’ blood glucose levels and the range for pre-diabetes and Type-2 Diabetes.

While these numbers might seem far from reach if you’re trying to manage your T1D o T2D on a standard western diet, making more intelligent food choices is potentially the most crucial factor for controlling the amount your glucose rises after eating. This is especially true for someone with Type-1 Diabetes.

The following chart shows the average rise in glucose for the 3,725 total Data-Driven Fasting app users.

In this relatively healthy group of people without Type-1 Diabetes, the average rise after meals is 16 mg/dL (0.9 mmol/L). In our Data-Driven Fasting Challenge and Macros Masterclass, we suggest Optimisers reduce their intake of carbohydrates if their glucose rises by more than 30 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) after meals.

However, we find that many people from a low-carb or keto background already have their carbohydrates low enough. Therefore, we guide these people to reduce their fat intake while optimising their protein and nutrients.

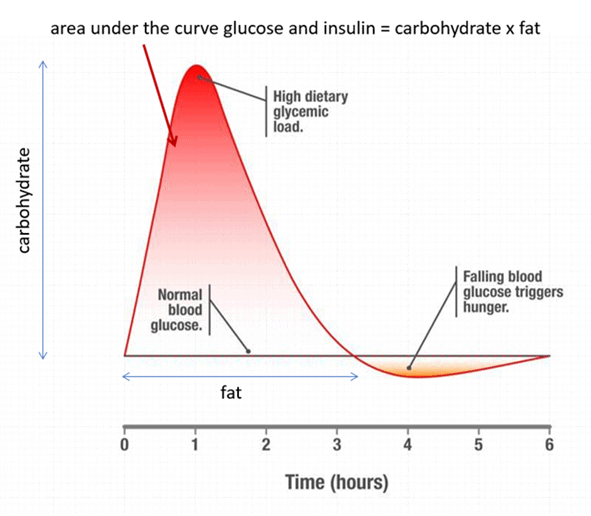

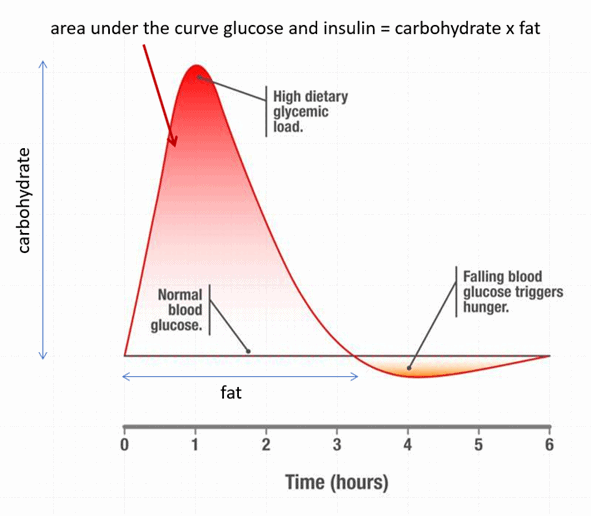

As we will see later, all food impacts blood glucose. People with a working pancreas (i.e., those without T1D) will see some glucose variation after eating. Carbohydrates raise glucose and insulin sharply, while fat keeps them both elevated for longer.

If you inject insulin, you need to be even more intentional with your food choices to manage the glucose rise after you eat.

For more details, see What are Normal, Healthy, Non-Diabetic Blood Sugar Levels?

Dr Bernstein’s Law of Small Numbers

Dr Bernstein’s Law of Small Numbers is the most elegant and powerful concept we’ve encountered for optimising Type-1 Diabetes management.

Your metabolism is complex and has many variables. Hence, it’s impossible to calculate perfectly how much insulin a certain amount of carbohydrate requires. As the image below illustrates, you can reduce your insulin dosage requirements and minimise dosing errors if you reduce your fast-acting refined carbohydrate intake at meals.

It’s not that carbs are necessarily better or worse than fat. However, it tends to be more of a ‘shot in the dark’ when someone tries to match their large carbohydrate intakes with large bolus insulin doses.

Injected Insulin is Different

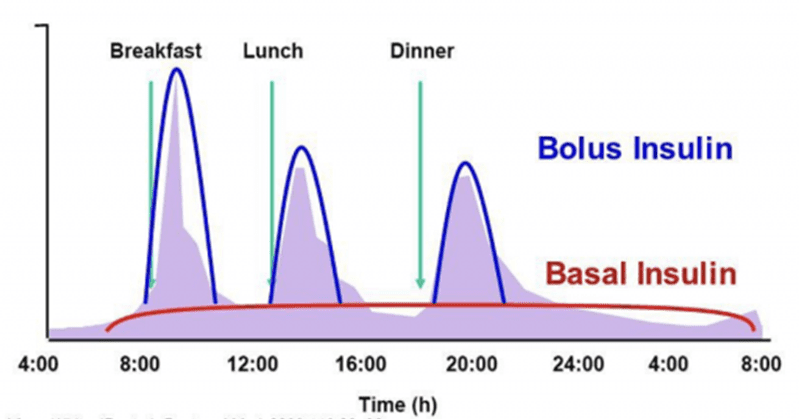

The biological half-life of insulin produced naturally in a healthy pancreas is between 3 and 10 minutes. However, as shown below, synthetic exogenous insulin works over a more extended period. Even the ‘rapid acting’ insulin will take five hours to clear from the system, while long-acting insulin works for up to 24 hours.

Additionally, smaller insulin doses are absorbed more quickly and work predictably. Meanwhile, larger insulin doses hang around in the body for much longer and lead to ‘overlapping’ insulin doses or ‘insulin stacking’! So next time you eat and try to calculate your bolus insulin, you have no idea how much insulin is still floating around in your system.

What Happens When Blood Glucose Rises Too High?

High blood glucose levels are dangerous and toxic to the body. When blood glucose levels are too high for too long, it can result in a condition known as glucotoxicity, which can contribute to increased oxidative stress. This is why nerve, eye, and cardiovascular damage are some of the top long-term side effects of poorly controlled diabetes.

In a healthy person, the pancreas maintains normal blood glucose levels. If your glucose rises higher than usual, your pancreas will produce and release more insulin to slow the release of liver glycogen until your body uses up the glucose in your blood.

There is a lot of confusion and fear around insulin. For more on how insulin works, check out What Does Insulin Do in Your Body?

If glucose levels are chronically elevated, the body can convert the excess glucose to fat—particularly saturated fat—in a process known as de novo lipogenesis. While this isn’t a concern for someone lean and metabolically healthy who occasionally has high glucose levels, someone who experiences high blood sugars and energy excess regularly can end up with fatty liver and fat deposition in the muscles.

In the short term, significant rises in glucose can lead to sudden drops in glucose in a condition known as reactive hypoglycaemia. Even for someone not injecting insulin, this can contribute to the ‘blood sugar rollercoaster’ or the increased cravings someone experiences when blood glucose falls below someone’s normal.

No matter how closely you track your carbohydrate intake or calculate your insulin dosing, there will always be errors and over-corrections due to influences outside your control.

Everyone with Type-1 Diabetes has horror stories of dosing too much insulin, which resulted in them mindlessly demolishing everything in the fridge and cupboard until they felt OK.

When our blood glucose drops due to excess insulin after excessive amounts of carbohydrates, we consume more nutrient-poor, low-satiety, energy-dense foods until we feel OK. This perpetual cycle of erratic blood sugar and insulin swings quickly leads to obesity and insulin resistance.

Many people simplistically view insulin as the hormone that makes us fat. However, the reality is that inaccuracies in insulin dosing can lead to crashing glucose levels, excessive hunger, which leads us to eat more than we otherwise need to. Obviously, in time, this makes us fat.

What are the Risks of Running Blood Glucose Too Low?

Most medical professionals don’t advise that people with Type-1 Diabetes aim for an HBA1c below 7% due to the risk of hypoglycaemia. However, once our glucose levels are more stable, we can shoot for a lower target and gradually reduce someone’s overall average to normal healthy levels.

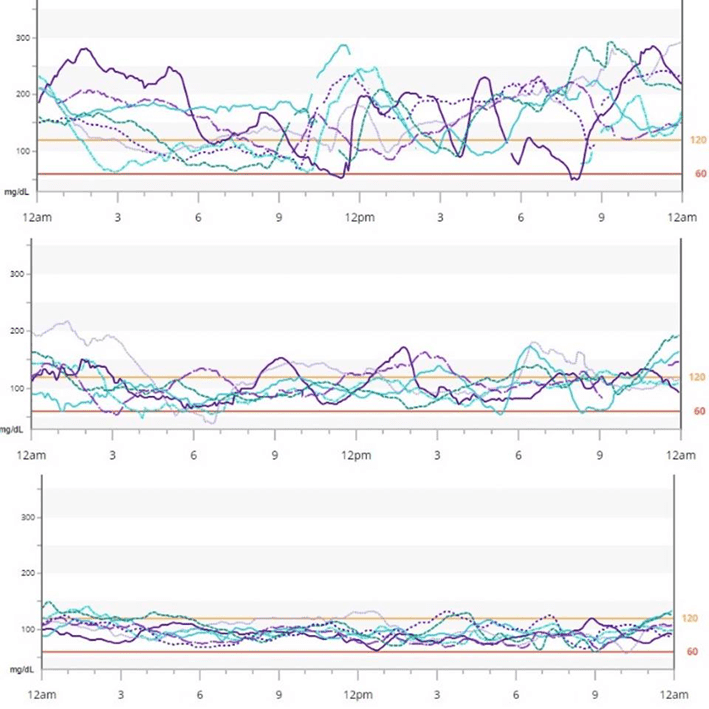

The image below shows typical glucose variability at various HbA1c levels. While achieving a healthy HbA1c is impossible if your blood glucose swings wildly, it’s much easier to accomplish when glucose levels are more stable.

Once you remove the variability, it’s safer to target normal healthy blood glucose levels. Have a look at the three charts below. Which one looks safer and less nerve-wracking to you?

What Happens to Glucose and Insulin Levels After Eating?

To some extent, all food affects insulin and blood glucose.

While most people know insulin as the anabolic hormone that forces glucose into cells, I find it more beneficial to consider the anti-catabolic role of insulin. That is, insulin works as the brake pedal that slows the release of stored energy into your bloodstream via your liver. Meanwhile, glucagon is the opposing ‘accelerator’ hormone that tells your liver to release stored energy when your blood sugar is low.

Carbohydrate

When you eat carbohydrates, your blood glucose levels rise rapidly. However, because your body can only store around 500 grams of glucose in the liver, muscles, and blood at any one time, the glucose must be used before other macronutrients like fat can be used for energy.

Thus, a healthy pancreas will rapidly increase insulin to slow the release of stored energy until you use up the excess glucose in your blood. Excess glucose not used by your body in the first two hours or so can be converted to saturated fat via de novo lipogenesis.

To mimic the action of a normal pancreas, someone with Type-1 Diabetes must inject enough insulin to match their carbohydrate intake.

Fructose

Carbohydrates are made of single (mono-) or multiple strings (di- and poly-) sugars (saccharides). There are three types of monosaccharides: fructose, glucose, and galactose. Fructose is commonly found in fruit.

Common table sugar is half glucose and half fructose. Pure glucose—which people with diabetes take to raise their glucose quickly—tastes quite bland. However, glucose becomes sweet and pleasurable when paired with fructose.

However, my analysis of the food insulin index data suggests that only 10% of the fructose in food impacts glucose, and only 30% elicits a rise in insulin over the first three hours after eating.

Fat

In contrast to carbs or protein, your body has a much greater storage capacity for fat. So, when you eat fat, your insulin levels rise less. Therefore, there is no emergency need to burn it off rapidly like there is with carbohydrates.

Your body loves to store fat and use it as an everyday fuel; fat fuels your body when you go for longer periods without food. Hence, it’s welcomed aboard as storage depots on your bum and belly.

However, as you increase your body fat reserves and exceed your Personal Fat Threshold, your pancreas must work harder to produce more insulin and keep that fat in storage. Although the fat in your diet may not increase insulin or blood glucose much after you eat, it will impact the basal insulin you require across the day.

Protein

Protein is perhaps the most interesting macronutrient. Metabolically healthy people who produce adequate insulin don’t tend to see their glucose rise after a higher protein meal; instead, they often see it fall.

In our Data-Driven Fasting Challenge, we use this as a hack to help people reduce their glucose which can be high in the morning due to the dawn phenomenon. If they are hungry and their glucose is higher, we encourage them to prioritise protein (with less fat and carbs) at their first meal. This improves satiety and lowers their glucose so they can eat another meal or two later in the day.

The body requires this insulin to use protein to repair and grow muscles and organs and to prevent excessive gluconeogenesis. While protein can be used to make glucose if carbohydrate intake is low, protein doesn’t turn to chocolate cake in your bloodstream or raise blood glucose if someone produces enough insulin.

My Food Insulin Index data analysis shows that protein requires about half as much insulin per gram as non-fibre carbohydrates over the first three hours. For example, my wife Monica doses insulin over the long term by setting an extended bolus in her pump for 50 g of ‘carbs’ she has a steak.

People eating a high-carb diet with diabetes usually don’t worry about injecting insulin for their protein because insulin for their carbohydrates dominates their insulin dosing. However, people on a lower-carb diet find it crucial to ‘cover’ their protein with insulin over the longer term.

Fibre

Humans lack the enzymes to break fibre down, absorb it, and convert it into usable energy. Hence, fibre generally has a minimal effect on blood glucose and insulin requirements. Consequently, most people with Type-1 Diabetes find it more beneficial to manage net carbohydrates, or the difference between total carbs, sugar alcohols, and fibre.

Net Carbs = Total Carbs – Carbs from Fibre – Carbs from Sugar Alcohols

Alcohol

Alcohol is like rocket fuel for your metabolism. Because of the principle known as oxidative priority, the body must utilise it before metabolising any other source of energy (i.e., protein, carbs, or fat).

Interestingly, alcohol doesn’t raise blood sugars or insulin; it actually lowers both in the short term. This is because your body slows the release of glucose into the bloodstream until it uses up the alcohol. Hence, people with T1D must lower their insulin after alcohol to stop their glucose levels from dropping too low.

Summary

The table below summarises our insulin and glucose response to each macronutrient.

| Insulin Response | Glucose Response | |

| Non-fibre carbohydrate | Large, short-term requirement. | Large short-term rise. |

| Fructose | 30% insulin requirement of starch and glucose. | 10% of the impact of starch and glucose. |

| Fibre | Negligible | Negligible. |

| Fat | Smaller, long-term requirement. | Slight, long-term rise. It tends to keep glucose from returning to baseline. |

| Protein | Requires 50% of the insulin that carbohydrates do in the first three hours. | Negligible glucose response. |

| Alcohol | Lowers. | Lowers. |

While it’s interesting to understand how your body typically responds to food, it’s impossible to accurately calculate the amount of insulin required to cover a meal like a burger, fries, and beer that’s a conglomerate of macronutrients.

Per Dr Bernstein’s Law of Small Numbers, you’ll never be able to accurately calculate the insulin dose for large amounts of foods that require a rapid insulin response. But we can control the largest inputs to minimise those errors so they can be easily corrected.

For more detail, see:

- Making Sense of the Food Insulin Index

- What Foods Raise Your Blood Sugar and Insulin Levels?

- Insulin Dosage Calculator for Type 1 Diabetes (including Protein and Fiber)

- Oxidative Priority: The Key to Unlocking Your Body Fat Stores

What Is the Difference Between Bolus vs Basal Insulin?

People injecting insulin split their dosing up into bolus and basal insulin doses.

- Bolus insulin is a substantial dose taken with food to ‘cover’ meals.

- Basal insulin is the ‘background’ dose required to maintain stable sugars throughout the day, regardless of whether someone eats.

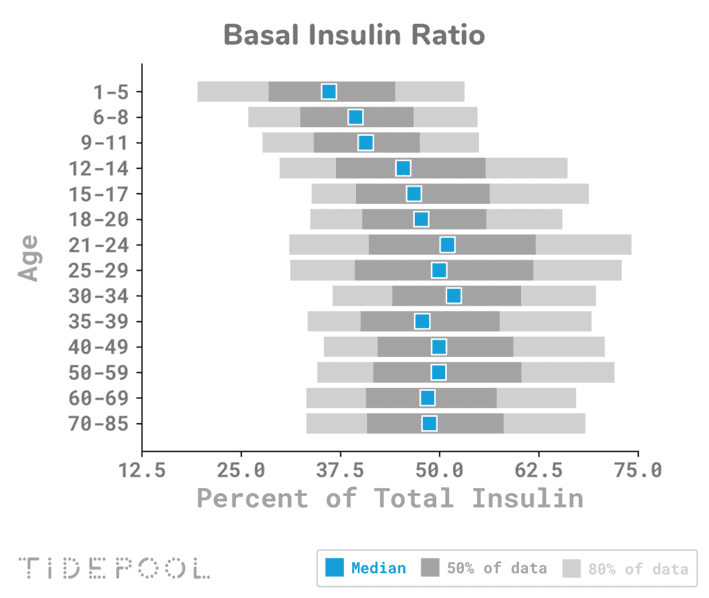

The chart below was taken from Tidepool’s collection of insulin pump data from Type-1 Diabetes users. Here, we can see that people on a standard western diet usually see a 50:50 split between basal and bolus insulin.

However, people on a lower-carb diet, like my wife and son, tend to see 70–90% of their total daily insulin administered as basal insulin, with much smaller correction doses required for their meals.

Factors that Impact Total Insulin Requirement

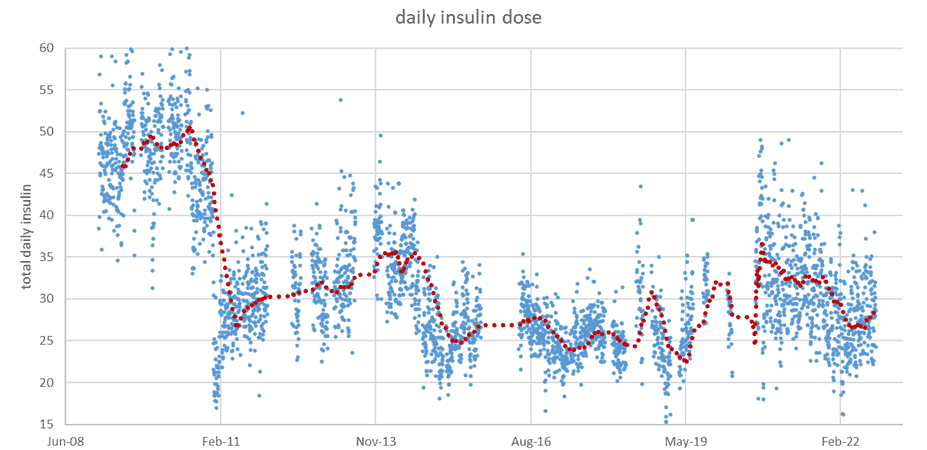

The chart below shows my wife Monica’s total daily insulin requirements since using an insulin pump in 2009. When we switched to a lower-carb diet in early 2011, you can see that her total daily insulin dose halved from around 50 to 25 units per day.

This photo of us is from before we reduced our refined carbohydrate intake. In the months that followed our transition to a diet with less refined grains and sugar and more meat, fish and vegetables, we both lost a lot of weight!

This next set of photos is of us before and after the first Nutrient Optimiser Masterclass in January 2019, a predecessor to the Macros Masterclass. Similar to our present Macros Masterclass, it also focused on high-protein %, nutrient-dense meals. During the challenge, Moni lost 7.5 kg or 10.7% of her starting body weight. Yes, she can be competitive, and yes, she lost more weight than me in my own challenge!

This chart illustrates a zoom-in of her insulin requirements during this period, which shows that her daily insulin requirements plummeted to 13 units per day during rapid weight loss!

To summarise, we can see that:

- a lower-carbohydrate diet requires less insulin,

- prioritising protein doesn’t increase insulin demand as many people fear,

- insulin requirements drop when there is an energy deficit, and

- total insulin requirements are lower if body weight is lower.

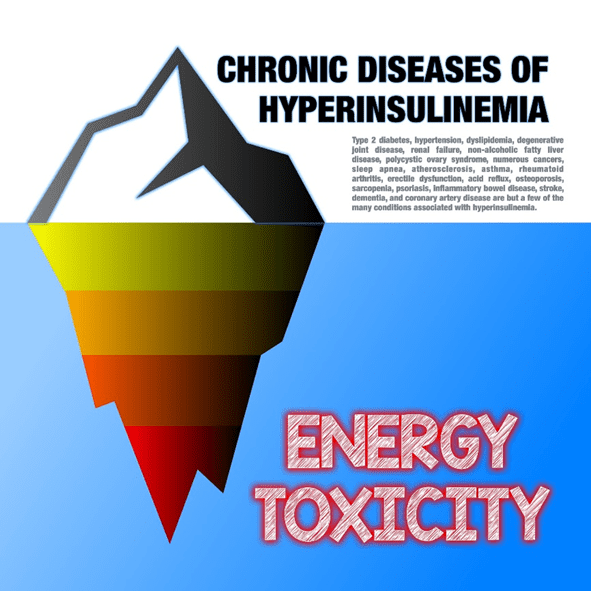

Energy Toxicity is The Root Cause of Insulin Toxicity

Many people these days are talking about hyperinsulinemia, ‘ insulin toxicity’, and insulin resistance as the root cause of metabolic disease. However, we can see from Moni’s insulin requirements through weight loss that energy toxicity, being too fat and exceeding someone’s Personal Fat Threshold is the real root cause of insulin resistance!

If you’re already eating lower-carb, your pancreas mostly produces basal insulin to keep your body fat in storage so you can use up the food coming in via your mouth. Like a dam trying to hold off floodwaters upstream, it requires more reinforcements (i.e., insulin) to hold more water back (i.e., more body fat).

While dietary carbohydrates are a factor, the most important thing you can do to reduce your insulin requirements is to eat a high-satiety, low-insulin-load diet that enables you to lose weight.

Whether or not you have Type 1 Diabetes, the key to reducing the total amount of insulin you require is not so much a matter of micromanaging what you eat to reduce insulin after your meal. Instead, it’s more a matter of eating in a way that provides greater satiety and allows you to lose weight sustainably. For more details on this, see

- The Real Reason You’re Insulin Resistant and The Macros to Reverse It, and

- Keto Lie #8: Insulin Toxicity is Enemy #1.

Insulin Dosing for People with Type-1 Diabetes

To some extent, optimal insulin dosing is a matter of trial and error based on the individual. Keep in mind that insulin requirements differ based on macronutrient intake, gender, age, stress levels, sleep, hydration, and a long list of other factors. Hence, a lot of tweaking and testing is standard in the early days as you find what works for you!

Total Daily Insulin Dose

Patients with Type-1 diabetes typically require a total daily insulin dose (TDD) of 0.5 to 1.0 units per kg per day. However, newly diagnosed patients may have lower initial requirements because they are still producing endogenous insulin. Someone recently diagnosed with T1D is given a conservative insulin dosing regimen that’s slowly increased if there are no low blood glucose levels.

After initial diagnosis and starting insulin, some T1Ds experience a ‘honeymoon period’ as their pancreas regains some function. Effectively, the beta cells get to rest and recuperate thanks to the exogenous insulin. However, this phase is unfortunately short-lived.

Insulin:Carbohydrate Ratio

The insulin:carbohydrate ratio (ICR) is the amount of insulin required to cover a certain amount of carbohydrates.

The ‘450 rule’ is often used to calculate an initial ICR. For example, if Total Daily Dose (TDD) = 50 units, the ICR = 450 / 50, which equals nine grams of carbohydrate per unit of insulin. Someone can then apply this to the foods they consume and adjust their insulin dose based on their carb intake.

This ratio is then tested and fine-tuned. If it’s not enough, the ICR is lowered to give more insulin per gram of carbs. In contrast, the ICR is increased to provide less insulin per gram of carbohydrates if their glucose falls too low.

Insulin Sensitivity Factor

The Insulin Sensitivity Factor (ISF) is used to calculate bolus corrections when glucose is above target without food.

The ‘120 rule’ is often used to calculate an initial ISF. For example, if TDD = 50, then ISF = 120 / 50 = 2.4, meaning every unit of insulin will decrease blood glucose by 2.4 mmol/L. Again, this ratio is an estimate that’s adjusted using trial and error.

How to Optimise Basal Insulin

While your ICR and ISF are important, basal insulin is the most critical element to get right. Basal insulin makes up around 50–90% of insulin dosing for someone with Type-1 Diabetes. Once you’ve fine-tuned your basal insulin rates, dosing for food is much easier.

Multiple Daily Injections

Previously, long-acting insulin like Lantus or Levemir was administered twice daily for basal insulin dosing.

If you wake up with high blood glucose, you will increase your night-time long-acting insulin—and vice versa—if you go low through the night.

Similarly, you’d increase your morning long-acting insulin if you’re higher throughout the day or reduce it if you’re going low. To check your basal doses, you would ideally fast for a period and adjust your basal dose based on how your body responds without food. However, this isn’t easy for most people, so it is not often done.

The most crucial factor here, and the most important takeaway to remember, is to make incremental steps to see the average effect over several days.

Insulin Pumps

Insulin pumps drip short-acting insulin (e.g., NovoRapid) in small doses throughout the day. One of the significant advantages of modern insulin pumps is that you can adjust the insulin dose every hour, which gives you much finer control.

Another key advantage is that you can reduce the rate at which basal insulin is released if your blood glucose is heading below target rather than having to eat something to raise your glucose levels.

Small changes can be made to remove insulin where glucose is going low or add insulin to keep it from getting too high. To manage this for my wife and my son, I created a spreadsheet that checks and tweaks their basal rates every week or two.

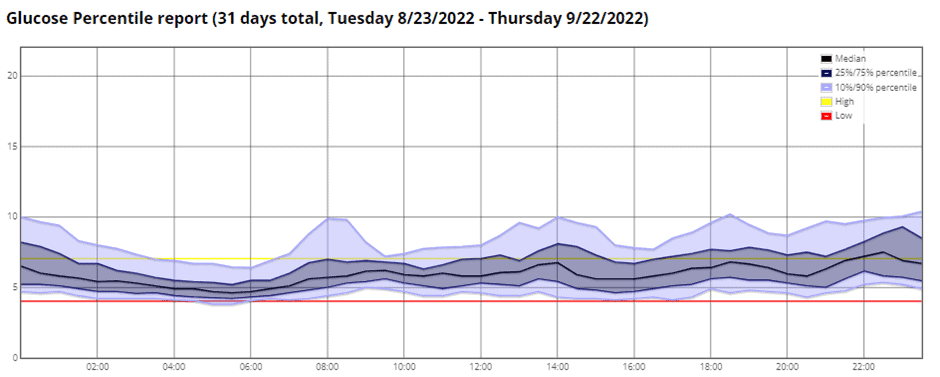

The Nighscout CGM percentile chart below shows that my son Mike has been a little low in the mornings. The red ‘danger’ line is set at 4.0 mmol/L, and I don’t want to see his 25th percentile blood sugar below this.

In the chart below, the new basal rate (blue line) drops two hours before he has been lower than what is desired. Conversely, the spreadsheet adds more insulin two hours before he’s typically exceeding the set threshold if he’s going high at specific times.

When tweaking basal rates, it’s critical to look at the long-term trends in blood glucose; I use a combination of two and four weeks. Incremental changes with regular reviews are better than occasional significant changes.

Technology for Type-1 Diabetes Management

Every few years, there is a promise in the media of a ‘cure’ for T1D. Unfortunately, nothing has yet materialised, and there’s nothing viable on the foreseeable horizon. However, some technologies, like the closed-loop insulin pump—have made a massive impact to help people with Type 1 Diabetes achieve normal healthy blood glucose levels.

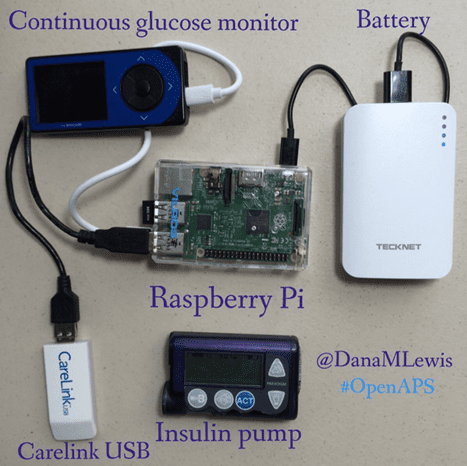

The DIY T1D community is way ahead of large medical device manufacturers in this area. Because they can experiment and iterate quickly on themselves and their families, they can create something that works brilliantly.

Dana Lewis and her OpenAPS collaborators have done just that and have been innovating this space for some time! We initially experimented with a closed loop system in 2018 and found it too complex and unreliable with all the DIY parts.

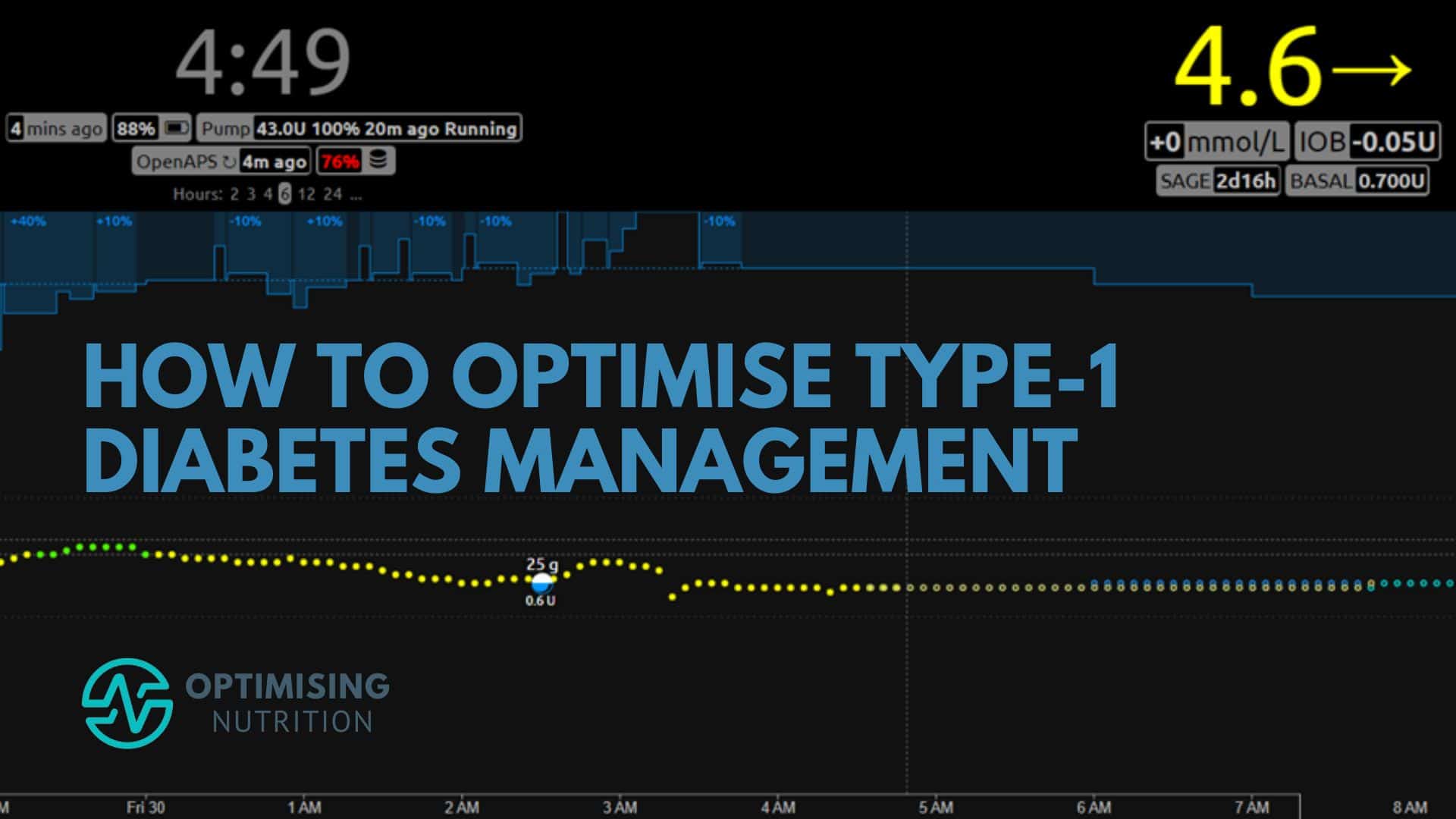

But a couple of years ago, Moni ‘upgraded’ to the AccuChek Combo pump with AndridAPS. It’s been an absolute game-changer! We copied David Burren’s set-up (shown below) that uses an Android phone and AndridAPS. If you’re interested in looping, I recommend checking out David’s Bionic Wookie blog for the latest developments in diabetes biotech.

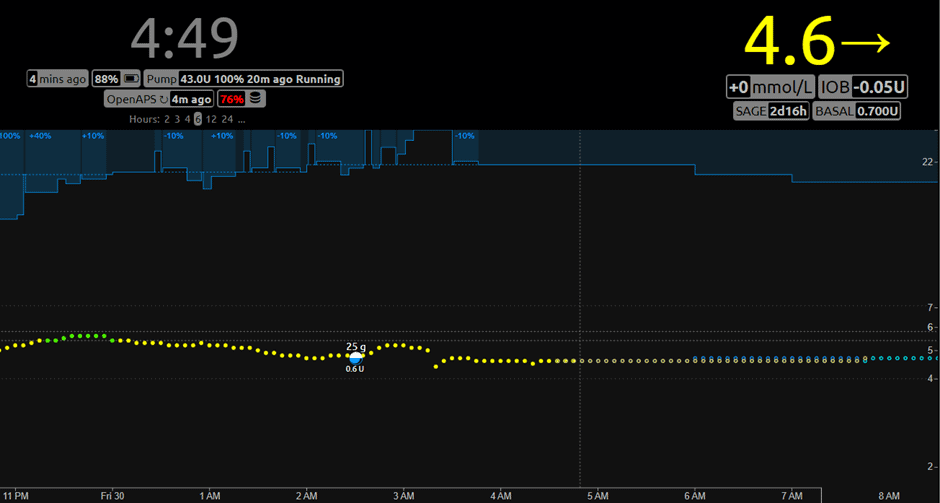

The NightScout screenshot below shows the closed-loop system in action. It adjusts the basal rates every five minutes based on where it predicts her blood sugars will be over the next six hours!

The blue bar at the top is her basal rate, which adjusts to ensure she stays within a normal healthy range. When she eats, and her glucose rises, the system releases small insulin doses through her pump to bring her glucose back into the target range. In addition, the autosense function constantly evaluates how she responds to insulin and adjusts her insulin sensitivity factor to nudge her basal rates up or down a little.

When Mike was diagnosed with T1D, we learned that Medtronic had bought the rights to the AccuChek Combo pump and had shut down production. Medtronic realised that everyone bought the Combo to loop, not their pump! Sadly, the Medtronic pump doesn’t allow you to target normal healthy blood glucose levels to achieve optimal control.

In March 2022, we settled on the YpsoPump for Mike, which is a great little pump. YpsoMed is currently rolling out a long-awaited update allowing closed looping using CamFX software, which seems like an excellent system for people who don’t want to delve into the detail. However, we’re looking forward to syncing Mike’s YpsoPump with AndroidAPS for greater control and fine-tuning.

While food choices are still the most critical input, a closed-loop insulin pump makes a massive difference. For example, a recent trial with the OpenAPS closed loop system showed a time-in-range increase from 61.2% to 71.2%. Another test run showed an Hb1Ac reduction of 0.3% with closed looping.

Many people find they needn’t announce meals with the Super Micro Bolus function and still get great control, especially if they consume fewer refined carbohydrates. Closed looping tends to make T1D safer, with fewer extreme highs and lows, but it’s still not a magic cure. But the most sophisticated algorithms and modern synthetic insulin still can’t deal with massive inputs of refined carbohydrates.

Again, managing the inputs that create the most variability is still critical.

How Does the Menstrual Cycle Affect Type-1 Diabetes?

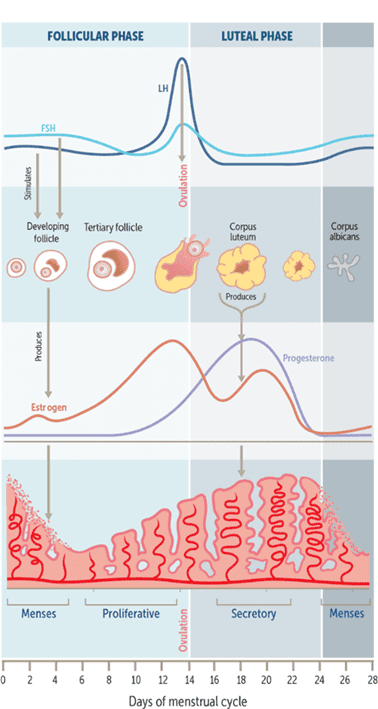

Another factor females with T1D must consider is the changes in insulin resistance and cravings throughout their monthly hormonal cycle. The figure below shows the hormone fluctuations across the monthly cycle.

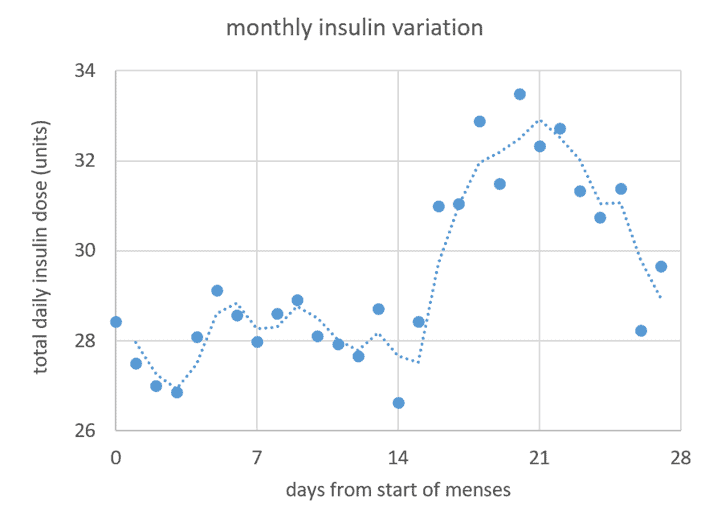

The following graphic shows Moni’s average total daily insulin dose across 23 cycles.

As we can see, her total daily insulin drops a little at the start of menses and on the day of ovulation. However, these are relatively minor changes compared to the increase between ovulation and menses. As we can see, her total daily insulin requirements largely follow the variations in progesterone across the month.

After ovulation, a woman’s body goes into building mode to grow a baby in case the egg she released is fertilised, and she becomes pregnant). Cravings for protein and energy increase to get the body the raw ingredients it requires. Additionally, she has become more insulin-resistant, so she will eat a little more.

To account for this each month, we bump up Moni’s basal insulin profile in AndroidAPS by 10% between days 16 and 26 of her cycle. From there, the autosens function and constantly adjusting basal rates take care of the rest.

For more, see Blood Sugar, Insulin and What to Eat for Each Phase of Your Monthly Menstrual Cycle.

Is a Low-Carb or Low-Fat Diet Optimal for Type 1 Diabetes Management?

The low-fat vs low-carb debate rages inside and outside the Type-1 Diabetes community.

Low-Fat

On one end of the spectrum, we have the Mastering Diabetes guy advocating for a low-fat plant-based diet with lots of fruit for energy. They correctly highlight that high-fat intakes cause insulin resistance and hence increased insulin requirements.

High-Fat

A few years back, keto was all the rage. Many people—including myself—fell into the trap of chasing ‘magical’ ketones by consuming a LOT of dietary fat. My friend and Type-1 Grit co-founder Allison Herschede found her total insulin dose doubled on a 90% fat, keto-style ‘diet’.

Allison said, ‘Taking my insulin was like injecting water. I realised I only had high ketone levels when I was insulin resistant! The only time I ever had high ketones was when I ate 90% fat’.

Allison’s HbA1c went up to 8.0% during her high-fat keto experimentation phase due to increased weight gain and the resulting insulin resistance! Thankfully, her Hb1Ac has returned to 4.8% after our Macros Masterclass and using our nutrient-dense, high-satiety meals.

For more detail, see Keto Lie #5: Fat is a ‘Free Food’ because it Doesn’t Elicit an Insulin Response.

Protein-Focussed Lower-Carb

The Type-1s—and non-T1Ds—I know with the best HbA1c, blood glucose levels, and metabolic health follow a protein-centric, carb-conscious diet.

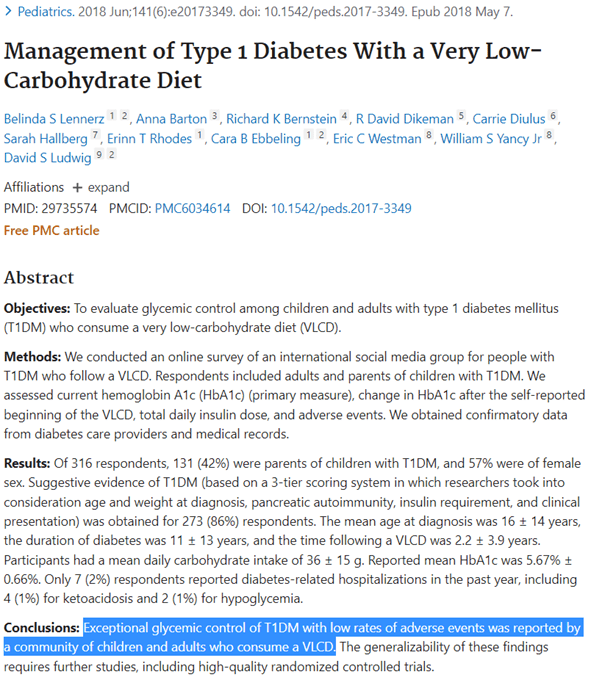

A 2018 study surveying 316 members of the Type-1 Grit Facebook found ‘exceptional glycemic control with low adverse events’ and a mean HbA1c of 5.67%.

Low-Fat vs Low-Carbohydrate

To some extent, the low-carb and the low-fat extremes both work because they avoid the hyper-palatable blend of carbs and fat that is commonplace in a standard western diet.

If you recall from our section on the effects of macronutrients, carbs spike blood sugars high over the short term, whereas fats raise blood sugars slightly over the longer term. Together, fats and carbs keep blood glucose high for long periods. The blend of fat and carbs with low protein is the signature of modern ultra-processed junk food that leads us all to overeat.

The official advice of dieticians and hospitals isn’t constructive, as they often recommend eating just like everyone else and compensating with insulin. Unfortunately, this is the same mainstream diet that has made even people with healthy pancreases fat, hungry, and sick. Adding exogenous insulin only accelerates the damage!

If you eat a pizza, carbonara or other hyperpalatable fat+carb combo foods, a closed-loop artificial pancreas will just ramp up insulin for many hours, and even days, to ensure all that energy is stored in your body.

For more detail, see Low-Carb vs Low-Fat: What’s Best for Weight Loss, Satiety, Nutrient Density, and Long-Term Adherence?

The Role of Carbohydrates

While they are sometimes demonised and feared, carbohydrates will always play a critical role for people with Type-1 Diabetes.

If blood glucose is low, some glucose tabs or fast-acting starchy carbs are the best way to bring glucose back to normal. Smart and experienced Type-1s know precisely how much glucose they need to bring their glucose up to target without overshooting.

Bringing blood glucose up in a controlled manner is the same approach we walk our Optimisers through in our Data-Driven Fasting challenges. If blood glucose levels are below average, someone’s first instinct is to reach for energy-dense, nutrient-poor comfort foods.

However, most people overconsume these high-glycemic index foods, which usually end up in sky-high blood sugars that someone must use insulin or medication to correct. Subsequently, someone is less likely to accurately correct higher blood sugars, meaning they are more likely to overdose with insulin.

If your blood sugar is high and you want to stabilise your glycemic variability, it makes sense to prioritise protein, get more of your energy from fat and reduce your current carb intake until you can control your blood glucose enough so that you can sleep at night.

This process of dialling up your protein and dialling back your fat and carbs to find the macronutrient ratio that fits your goals and preferences is the exact method we teach in our Macros Masterclass.

For more detail, see High Protein vs High Fat: What’s Ideal for YOU?

How to Find the Ideal Macros Balance for Your Type-1 Diabetes

In the end, everyone has their preferences, but from my analysis and experience, I believe it comes down to simply:

- Ensure adequate protein intake,

- Moderate carbohydrate intake to achieve healthy blood glucose variability (e.g., a rise of less than 30 mg/dL or 1.6 mmol/L after meals, and

- Moderate fat intake (i.e., less fat if your goal is weight loss or more fat to fuel activity levels if you are lean and want to grow).

For more details, see:

- What Are Macros in Your Diet (and How to Manage Them)?

- Protein – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR),

- Carbohydrates – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR), and

- Fat – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR).

How to Not Lose Your Mind

Type-1 Diabetes is hard; you just have to choose your hard.

Changing how you eat is not easy. But neither are the symptoms related to being on an endless blood sugar rollercoaster (i.e., hormonal imbalance, unpredictable energy, poor sleep, lethargy, reduced lifespan etc.) or the numerous complications that often result from poor glycemic control.

This article has highlighted the benefits of achieving optimal blood sugars and how to do it. However, you should be prepared to take your time getting there. Most people don’t manage to make radical changes overnight and stick to them. Hence, we constantly advocate for small, consistent, and constant changes that slowly build self-reinforcing habits throughout our challenges.

Moving towards your optimal takes progressive self-reflection and iteration. Gaining optimal control takes a level of dedication and focus that not everyone can muster, but we believe everyone can move in that direction! Once you achieve more stable blood glucose values, you can slowly lower your target glucose.

Start by taking notice of the foods and meals that boost your blood glucose the most vs the least. Try to eat more of the ones that keep your blood glucose in the normal range and require less insulin.

In time, you’ll find a short list of foods and meals that work for you and your family.

What Are the Best Foods for Type-1 Diabetics to Eat?

Ten years ago, I started creating food lists suitable for different goals.

My initial motivation was to find foods and meals to help my wife stabilise her sugars while still getting the necessary nutrients. To date, I’ve created more than seventy nutrient-focussed food lists for different goals and preferences that you can access here in our Optimising Nutrition Community.

If your blood sugars rise by more than 30 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) after meals, you’ll find the Low-Carb and Blood Sugar food lists helpful. The Blood Sugar and Fat Loss list would be even more ideal if you are also trying to lose some fat.

In addition to our food lists, we have created a suite of NutriBooster recipe books tailored toward various goals. Again, the Low-Carb & Blood Sugar book helps stabilise your blood sugars. Meanwhile, the Blood Sugar & Fat Loss book is more useful if you also have body fat to lose. You can learn more about our optimised NutriBooster recipes here.

Finally, if you need extra help and guidance dialling in your macros to achieve healthy, stable blood glucose levels, you may be interested in our four-week Macros Masterclass. In these four-week challenges, we guide our Optimisers to understand their current diet and progressively tweak it to move toward their optimal.

Summary

- Type-1 Diabetes is a complex and challenging condition. But people with Type-1 Diabetes can achieve normal blood sugars and live healthy lives with intelligent food choices.

- Due to numerous factors beyond our control, it’s impossible to accurately match insulin dosing with food. The most effective approach is prioritising foods and meals that cause less aggressive rises in blood sugars and cause minor errors that can easily be corrected.

- More stable blood sugars can be achieved by:

- Ensuring adequate protein intake,

- Reducing intake of refined carbohydrates to reduce the rise after eating to normal healthy levels (e.g., an increase of less than 30 mg/d or 1.6 mmol/L), and

- Leveraging dietary fat by dialling fat up if you need more energy to support activity levels or growth for lean people or down if fat loss is a goal.

More

- What Are Macros in Your Diet (and How to Manage Them)?

- Low-Carb vs Low-Fat: What’s Best for Weight Loss, Satiety, Nutrient Density, and Long-Term Adherence?

- High Protein vs High Fat: What’s Ideal for YOU?

- Carbohydrates – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR)

- Macros Masterclass

Thank you Marty for such a comprehensive article and references. 3 comments: 1) my diabetes control as a T1D for 56 years has recently been compromised by sciatic nerve pain. So stresses can upset the bsl ‘applecart’ and need attention – i am lining up for an operation to get this sorted – somehow i have still managed a recent HBA1C of 5.5% on mdi but gained some weight in the process. Whatever is causing insulin resistance get it sorted. 2) i agree that fat-heavy diets play havoc with my bsl control and i wonder if part of the issues is a late post-prandial sirge of glucagon after a fatty meal , something a person with T2D and working pancreas can better deal with automatically compared to a T1D? 3) i have yet to receive a good answer to the following: i have heard Stephen Phinney opine that eating a meal heavy in carbs and saturated fat is deleterious as high blood fats can result. So does this mean that T1Ds and many T2Ds who have say a high bsl before a meal ( say > 10 mmol/l) should avoid eating fat, particularly saturated fat, until their bsl normalises ( e.g. to say < 6.7 mmol/l?

Thanks Anthony. Sciatica seems to be one of the many conditions common for people with T1D. My wife Moni had a lot of sciatica pain and carpel tunnel. She actually had her carpel tunnel syndrome operated on maybe 15 years ago when she was taking a LOT more insulin and heavier than she is now. Thankkfully she now has no symptoms.

Despite the high-fat keto fad, I don’t think anyone handles an extremely fat-heavy diet well. I discussed this a bit more in part 5 of BFKL – https://optimisingnutrition.com/too-much-fat-keto/

In our DDF Challenges we see that ton’s of fat at night tends to lead to more elevated waking BGs. People also have to wait a lot longer for their blood sugar to drop below normal before needing to refuel. When T1Ds don’t dose with insulin for a fat bolus they tend to see a rise in BG 3-9 hours after eating.

Fat+carb is the signature for hyerpalatable modern processed junk food. The form of fat makes a small difference, but I generally focus on total fat intake. Saturated and monounsaturated fat behave slightly differently, but they’ll both make you fat and insulin resistant if you eat them in excess. See https://optimisingnutrition.com/does-eating-fat-make-you-fat/

Thank you Marty for sending me this well done article, even the title had me smiling! After dealing with T1D for 42 years I can so relate to what your family has gone through. I especially appreciated your upside to T1D, something I’ve never seen mentioned elsewhere. I have found that to be true in my case as well, which is truly amazing. Thank you for sharing!

Thanks Lori! It’s been great to see you dialing in your T1D control in the Macros and Micros classes!

So much of the right information packed into one article. Thank you Marty!

I have few friends living with Type 1 diabetes the wrong way!

thanks so much. I’ve had a number of people ask for something more specific around T1D so I thought it would be good to do a thorough brain dump of all the protips we’ve picked up. I hope our journey and learnings can help others. we’re so grateful to all the people who have taught us so much!