Over the past few years, many people have been led to believe that:

- insulin toxicity is the root cause of the majority of our western diseases,

- insulin is public enemy No. 1, and

- reversing ‘insulin toxicity’ is the key to weight loss and health.

Contrary to popular belief, the menace isn’t insulin toxicity but rather—energy toxicity. Insulin is really just trying to do its job in the face of an onslaught of low-satiety, nutrient-poor, hyperpalatable foods that cause us to eat more than our bodies require!

Delve into the dynamics between our dietary choices, insulin levels, and the unseen peril of energy overload.

- Is Fat a ‘Free Food’ Because #Insulin?

- It’s Not Insulin Toxicity, but Energy Toxicity

- What is Diabetes?

- Net Carbs vs Total Carbs vs Processed Carbs?

- Double Diabetes

- What’s the Solution?

- How to Optimise Your Diet for Fat Loss and Reduce Insulin

- How to Optimise Your Type 1 Diabetes Management

- What the experts are saying

- Get Big Fat Keto Lies!

- More

Is Fat a ‘Free Food’ Because #Insulin?

However, the problem with thinking in terms of ‘insulin toxicity’ comes when we add the belief that carbohydrates and protein will raise insulin (i.e. the Carbohydrate Insulin Hypothesis of Obesity) and hence dietary fat is practically a free food.

The reality is we don’t have a lot of data about our insulin response to the food we eat. As shown in the example below, the data we do have (from the Food Insulin Index testing) only measures the short-term insulin response to foods over the first two hours.

Many people extrapolate this data from the measurements we have over two hours and assume fat has no insulin response and hence they can eat almost unlimited dietary fat and t that fat is effectively a ‘free food’.

While glucose will raise your insulin levels quickly, foods that contain fat and carbs together (like milk, shown by the aqua line in the chart above) will have a smaller initial impact, but insulin will stay elevated after two hours.

While we don’t know that much about the long-term insulin effect of high-fat foods, it appears they also will keep our insulin levels higher over the longer term. And because fat is stored more efficiently, you don’t need as much insulin to hold it in storage on your butt and belly.

It’s Not Insulin Toxicity, but Energy Toxicity

Once we understand that insulin just holds our stored energy back while we use up the energy coming in from our diet, we realise that ALL food will increase insulin, to some degree, over the long term.

The fundamental problem is not insulin toxicity but rather energy toxicity.

It’s the excess energy that leads to increased insulin levels. Hence, the solution to decrease insulin levels is to:

- modify our food choices to achieve healthy (but not necessarily flatline) blood sugar levels, and

- reduce the amount of stored energy that requires insulin to hold in storage.

What is Diabetes?

Fundamentally, diabetes is a condition of insulin insufficiency.

- The pancreas of someone with Type 1 Diabetes cannot produce enough insulin to maintain stable blood sugars. There is often an initial ‘honeymoon period’ where their pancreas still produces some insulin, but in time, most people with Type 1 Diabetes produce no insulin at all. Hence, they need to take injected insulin to have enough insulin to achieve stable blood sugars.

- People with Type 2 Diabetes can produce plenty of insulin. However, because they have so much energy to hold in storage, their pancreas cannot keep up (insulin production is insufficient), and they see some of their stored energy overflows into their bloodstream.

Net Carbs vs Total Carbs vs Processed Carbs?

One of the common debates in low-carb and keto circles is whether they should be worrying about net carbs, total carbs or processed carbs to manage blood sugars, ketones, and insulin.

Processed carbs

It’s often more helpful to talk about avoiding processed carbs. For most people, this is adequate. If you are trying to avoid nutrient-poor, low-satiety foods, then avoiding foods that involve refined sugars and starches is adequate.

As shown in the satiety vs nutrient density chart here, it’s typically these refined carbs that are added to ‘vegetable oils’ that end up being ‘bad carbs’ that people intuitively know that they should avoid (e.g. doughnuts, cookies, croissants, etc.).

Meanwhile, there is no need for most people to avoid non-starchy vegetables. They will be hard to overeat, and you will get plenty of the harder-to-find nutrients per calorie.

Net carbs or non-fibre carbs?

“Net carbs” refers to the total carbohydrates minus the fibre in your food.

Net Carbs = Total Carbohydrates – Carbohydrates from Fibre

It’s hard to overeat foods that naturally contain a lot of bulk and fibre. Fibre doesn’t count towards your overall calorie intake because, for the most part, it isn’t digested in your gut to provide calories or significantly raise your blood sugar.

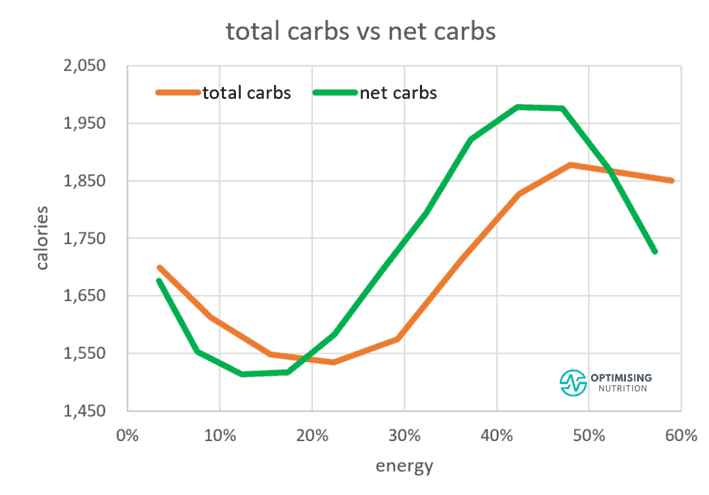

The chart below shows how thinking about net carbs can be more effective to dial in satiety. Moving from moderate to lower total carbohydrates aligns with a 21% reduction in calories. In contrast, decreasing net carbs instead gives us a more substantial 29% reduction in calories.

For the most part, fibre is not available to be used by your body for energy and hence will not raise blood sugars or insulin. It is fermented in the gut to feed gut bacteria or is excreted undigested.

Fibre is not necessarily a goal that you need to strive to get a certain minimum amount of. However, nutrient-dense, high-satiety foods tend to contain plenty of fibre.

The problem with thinking in terms of total carbs rather than net carbs is when we have people who want to lose weight, avoiding foods like lettuce, broccoli and spinach for fear they will be getting too many carbohydrates because it will kick them out of ketosis, spike their insulin and make them fat.

If you find you are insulin resistant and your blood sugars rise more than 1.6 mmol/L (or 30 mg/dL) after meals, then it can be helpful to think in terms of managing your net carbs or non-fibre carbs.

If you are working to a carbohydrate limit, we recommend that most people think about ‘net carbs without sugar alcohols’ (you can select this setting in Cronometer).

Sugar alcohols are typically contained in processed foods to make them sweeter and more palatable (hence you will likely eat more of them). Some of them will raise your blood sugars while others won’t (see the glycaemic index of sweeteners here).

Double Diabetes

The line between Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes is not always clear. Some people develop what is known as ‘Double Diabetes’.

For someone with Type 1 Diabetes, years of injecting large amounts of insulin that drive hunger and overeating mean they develop increased insulin resistance due to increased levels of body fat. As a result, they require more basal insulin to hold their stored energy in storage when not eating, and when they do eat, they will need more insulin for their meals. When people with Type 1 Diabetes lose weight, we see their basal insulin requirements plummet, and their insulin sensitivity improves, so they need less insulin for meals.

Conversely, someone with Type 2 Diabetes, after a number of years, may find their pancreas effectively burns out, and their beta cells are no longer able to produce as much insulin. At this point, they will need to take more and more insulin.

Sadly, two-thirds of the insulin produced today is used by people with Type 2 Diabetes, which could potentially be avoided with diet and exercise. People with Type 1 Diabetes may be taking 10 to 40 units of insulin per day, while someone with poorly controlled Type 2 Diabetes may be taking more than 200 units of insulin per day due to their extreme insulin resistance.

What’s the Solution?

If we want to maximise our insulin sensitivity and lose fat from our body, it’s not merely a matter of eating fewer carbs and more fat, as some people would have us believe.

Modifying our diet (i.e. reducing processed carbs) will only marginally decrease the insulin requirements in response to meals (i.e. bolus insulin).

While reducing the processed carbohydrates in your diet will help to reduce the amount of insulin required for meals, we need to keep in mind that the basal insulin (i.e. the insulin produced by our pancreas or injected to maintain stable blood sugars when we don’t eat) comprises the majority of the insulin requirements across the day.

In someone consuming a typical high-carb diet, basal insulin makes up around 50% of their insulin requirements. However, for someone following a low-carb or keto diet, basal insulin may make up 80 to 90% of their total daily insulin dose (TDD).

To reduce insulin, we need to optimise our diet for greater satiety, which will lead to a reduction in stored energy, lower blood sugars, improved insulin sensitivity and reduced basal insulin. Additionally, improvements in insulin sensitivity will lead to reduced insulin requirements for food.

How to Optimise Your Diet for Fat Loss and Reduce Insulin

Stabilise Blood Sugars with Better Food Choices

In our Macros Masterclass and Data-Driven Fasting, we encourage people to monitor their blood sugar rise after meals. If blood sugar rises by more than 1.6 mmol/L (or 30 mg/dL), then it is a great idea to look to reduce the carbohydrates (i.e. net carbs or non-fibre carbs) to the point that the blood sugars stabilise to healthy, non-diabetic levels.

However, if your blood sugars are already below this threshold, there is little value in trying to stabilise your blood sugars even further, especially if this involves swapping out carbohydrates for fat. On the other hand, if you already have healthy blood sugar levels, then you can get on with prioritising nutrient density and satiety.

Prioritise Satiety and Nutrient Density

If you still have body fat to lose, the next step is to simply prioritise foods and meals that provide greater satiety and nutrient density (they typically go together). In the Macros Masterclass, we use Nutrient Optimiser to guide you to:

- ensure you are getting adequate protein to prevent loss of lean muscle mass;

- dial back non-fibre carbohydrates (if blood sugars are still elevated);

- dial back dietary fat (to allow body fat to be used); and

- prioritise foods and meals that contain more of the nutrients you are struggling to get enough of.

This process can continue until a healthy level of body fat is achieved (i.e. waist:height ratio of less than 0.5 or less than 15% body fat for men and less than 25% body fat for women). By doing this, we will reduce both basal and bolus insulin requirements and vastly improve insulin sensitivity.

For more detail, see Macronutrients [Macros Masterclass FAQ #2].

Meal Timing

In the Data-Driven Fasting Challenge, we use pre-meal blood sugars to guide meal timing to ensure an overall energy deficit is being achieved. If blood sugars are low and stable, but weight loss is not occurring, then we encourage people to increase the protein percentage of their meals by dialling back dietary fat to allow body fat to be used.

If your blood sugars are already in the healthy range and you are not injecting insulin to manage your diabetes, rather than worrying so much about your rise in blood sugars and insulin after meals, it’s more beneficial to monitor your blood sugars before meals and delay/or skip them until they return to below your baseline.

Waiting for your blood sugars to return to baseline will ensure you are not over-fuelling. But waiting a little longer until they are a little lower empowers you to validate your hunger and ensure a long-term energy deficit that will reverse energy toxicity.

How to Optimise Your Type 1 Diabetes Management

The process is similar to the process above, with the following additional considerations if you are injecting insulin.

- Monitoring blood sugar becomes important to ensure basal insulin is titrated back to prevent low blood sugars (i.e. less than 4.0 mmol/L or 72 mg/dL). As you lose fat, you will require less basal insulin to keep your blood sugars stable when you don’t eat.

- If you are using an insulin pump, you will need to increase your Insulin Sensitivity Factor (i.e. the amount by which a certain amount of insulin will lower your blood sugar). You will also need to increase your insulin-to-carb ratio as you will need less insulin for a given amount of carbohydrates.

- Finally, once your blood sugars stabilise and there is less variability, you can target a lower average blood sugar across the day to achieve an average blood glucose level similar to a metabolically healthy person. For example, if you have not experienced a blood sugar below 4.0 mmol/L or 72 mg/dL for the past week, you can target a slightly lower blood sugar for the coming week.

What the experts are saying

Get Big Fat Keto Lies!

Get your copy of Big Fat Keto Lies.

More

- Big Fat Keto Lies: Now On Kindle

- Big Fat Keto Lies: Introduction

- A Brief History of the Low Carb and Keto Movement.

- Keto Lie #1: ‘Optimal ketosis’ is a Goal. More Ketones are Better. The Lie that Started the Keto Movement.

- Keto Lie #2: You Have to be ‘in Ketosis’ to Burn Fat.

- Keto Lie #3: You Should Eat More Fat to Burn More Body Fat.

- Keto Lie #4: Protein Should Be Avoided Due to Gluconeogenesis.

- Keto Lie #5: Fat is a ‘Free Food’ Because it Doesn’t Elicit an Insulin Response.

- Keto Lie #6: Food quality is Not Important. It’s All About Reducing Insulin and Avoiding Carbs.

- Keto Lie #7: Fasting for Longer is Better.

- Keto Lie #8: Insulin Toxicity is Enemy #1.

- Keto Lie #9: Calories Don’t Count.

- Keto Lie #10: Stable Blood Sugars Will Lead to Fat Loss.

- Keto Lie #11: You Should ‘Eat Fat to Satiety’ to Lose Body Fat.

- Keto Lie #12: If in Doubt, Keep Calm and Keto On.

- Resources

Nicely explained Marty.

Thank you!!!

Very interested by your approach , thank you for the book

thank you! so glad you enjoyed it!

I would like to gain weight. Hipertrophy. Talk about please!

Lean bulking is basically a matter of getting enough protein and then adding energy from carbs and fats to gain weight slowly, so you gain mostly muscle, not just fat. See https://optimisingnutrition.com/calculating-target-macros/

Thank you so much.

Hello from Brazil!

Cheers. Glad you found it helpful.

Good timing Marty – Craig Emmerich said exactly the same thing on Vanessa Spina’s podcast today. He didn’t mention you though, but I have a sneaky suspicion he was borrowing from your material since it was almost word for word from Keto Lies…

Seems like your intuition might be well calibrated. It’s satisfying to see the content of BFKL spreading through the keto community.