It’s common knowledge that vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and essential fatty acids are good for us.

We are continually told we eat a nutrient-poor diet, so we need more nutrients.

Bruce Ames’ Triage Theory shows us that we will not just survive for the short term if we get more of all the essential nutrients, but we will thrive over the longer term.

But the all-too-common ‘solution’ recommended and usually advertised to us is to simply:

- ‘Buy my new supplement X that will cure ailment Y’—that you didn’t know you had; or

- Add a heap of synthetic vitamins to whatever ultra-processed food you prefer to make the label look better.

But, when it comes to nutrients, it’s critical to ask and know,

- How much is too much?

- At what point are we wasting our valuable time, money, and finite amounts of focus on chasing more nutrients with supplements?

- Could the ‘more-is-better’ approach to supplementation and fortification be detrimental to our health and waistlines?

- Despite the cost, and the marketing that goes into commercial supplements, are the nutrients they contain equal to those found in foods, or do they provide us with inadequate levels of supplementation that aren’t absorbed or utilised as well compared to whole foods?

In this article, we’ll dig into the data to answer these important questions.

Your body quickly excretes any excess supplements you consume, creating brightly coloured, expensive pee. But as you will see, we have distinct cravings for each nutrient.

As a result, obtaining your nutrients from supplements and fortified foods could decrease your appetite for whole foods that elicit greater satiety.

- The Data

- How Much Is Too Much?

- Nutrient Leverage

- What Happens If You Overdo Your Mineral Supplements?

- The Optimal Nutrient Intakes

- What Happens When We Consume Too Much a Nutrient?

- What Nutrients Are Supplemented Most Frequently?

- Nutrients That Have Decreased While Obesity Has Increased

- Nutrients that Correlate with Rising Obesity Rates

- Nutrients that We See a Rebound Satiety Response To

- Pros and Cons of Fortification

- Why Is There a Greater Calorie Intake with Supplementation and Fortification?

- We’re Being Fed Fortified Pig Slop!

- Could Supplements and Fortification be Bad for You?

- Should You Take Supplements?

- Summary

- More

The Data

We now gathered one hundred and fifty thousand days of food logging data from forty thousand people who have used Nutrient Optimiser over the past five years in our four-week Macros Masterclass and Micros Masterclass, as well as those who have taken our free 7-Day Nutrient Clarity Challenge to assess their typical diet without doing a class.

As you will see, this enormous data set provides powerful insight into how we respond to the nutrients in our food at excess and deficiency extremes.

How Much Is Too Much?

In our Micros Masterclass, we encourage people to dial back their supplementation and intake of fortified foods—which tend to be ultra-processed—once they can obtain the DRI from whole foods alone.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to eliminate fortified foods and supplements from our Optimiser dataset. However, while supplementation tends to dilute the quality of the data analysis, we can also use it to analyse the effects of synthetic nutrition to understand whether it helps or hurts satiety and how many calories we consume.

Nutrient Leverage

Generally, people who obtain more of each essential nutrient per calorie tend to eat less, at least when they are getting normal ranges of nutrients only from whole foods.

Our analysis shows we have a unique satiety response to foods containing more of each essential nutrient, and we appear to crave more of these foods until we get what we need.

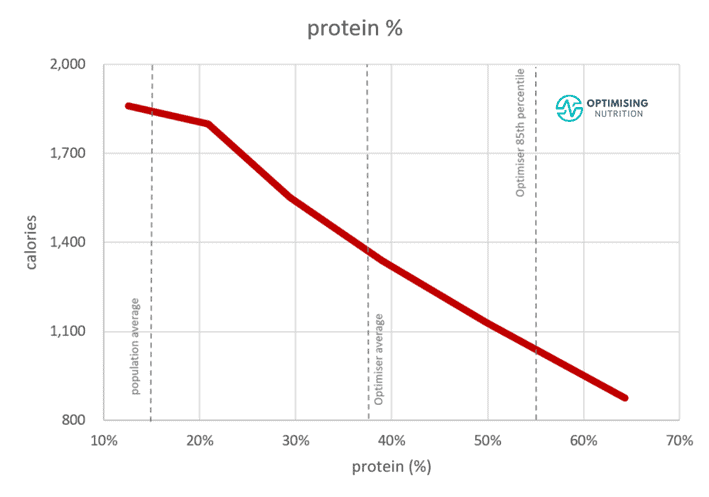

If you’ve been following the Optimising Nutrition blog, you may know I’m a big believer in the Protein Leverage Hypothesis. The Protein Leverage Hypothesis states that all organisms, including humans, continue to eat until they consume adequate amounts of protein. Hence, consuming low-protein, processed, fat-and-carb combo foods (i.e., modern-day ‘junk’ food) will have you eating a LOT of calories without feeling very satiated. As shown in the chart below from our analysis, a higher protein % aligns with a significantly lower overall energy intake.

But rather than just protein leverage, we see a more general nutrient leverage effect from all the vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and essential fatty acids. So, like a nutrient-seeking monster, your appetite will keep you munching through as you must consume to get the nutrients you need.

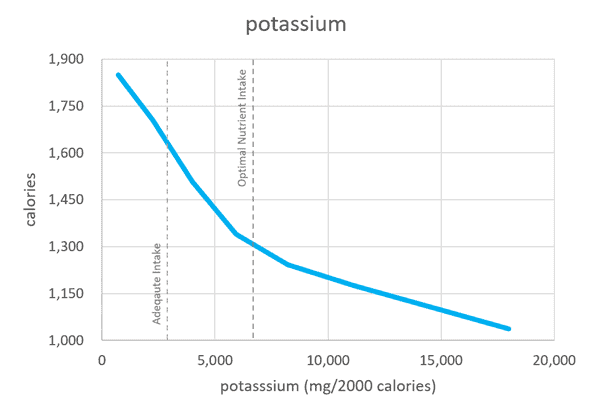

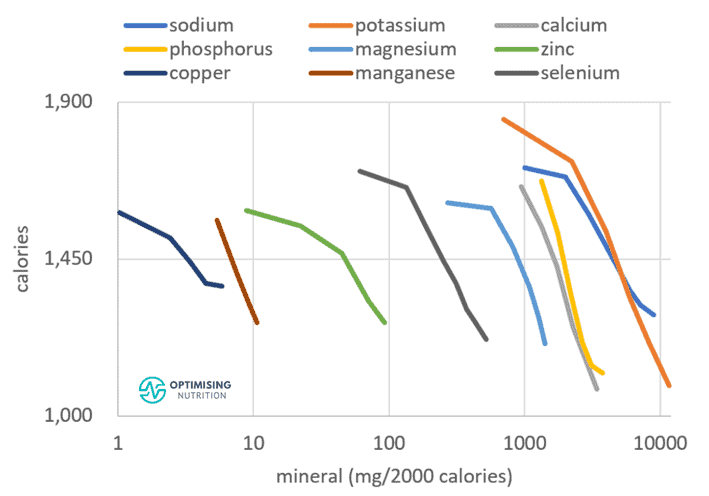

As you can see from the charts below, we have a strong satiety response that just ‘keeps on giving’ for some of the larger macro minerals like potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sodium.

What Happens If You Overdo Your Mineral Supplements?

As we get more of those nutrients per calorie (i.e., we increase our nutrient density), our overall energy intake decreases. So, we often reach a point where more is not better for these macro minerals. However, we don’t see a rebound satiety effect with the larger minerals (i.e., more = worse).

This doesn’t mean you should go out of your way to supplement with these unless there is absolutely no way you can get them from food.

- Your gut will quickly tell you when you’ve overdone it on potassium, magnesium, and sodium; you’ll be on the toilet and drinking heaps of water in an attempt to clear them!

- Potassium supplementation is typically advised against because it can interfere with blood pressure medications, which help you retain potassium.

- Studies have shown that calcium supplementation tends to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. When calcium is consumed without adequate amounts of other cofactors—like vitamin D, K, magnesium, manganese, and potassium—naturally found in calcium-rich whole foods, calcium can deposit in the arteries, muscles, and brain.

- All of the macro minerals are synergists (nutrients that work together) and antagonists (nutrients that decrease one another) of each other. Hence, taking extremely high amounts of one micromineral can increase your demands and create a deficiency in another.

The Optimal Nutrient Intakes

Nutrients are critical. But as you will see, more is not always better!

Much like the Law of Diminishing Returns in economics, there is a limit to the benefit of many nutrients, particularly when they come from synthetic sources.

The data from Optimisers has enabled us to develop our new satiety index, which uses a particular food or meal’s nutrient profile to estimate how much of it you’ll eat. These ‘cheat codes for nutrition’ enable us to quiet the noise of the ongoing low-carb vs low-fat, plants vs animals, or protein vs no-protein debates to ensure we’re simply giving our bodies what they need from the food we choose to eat.

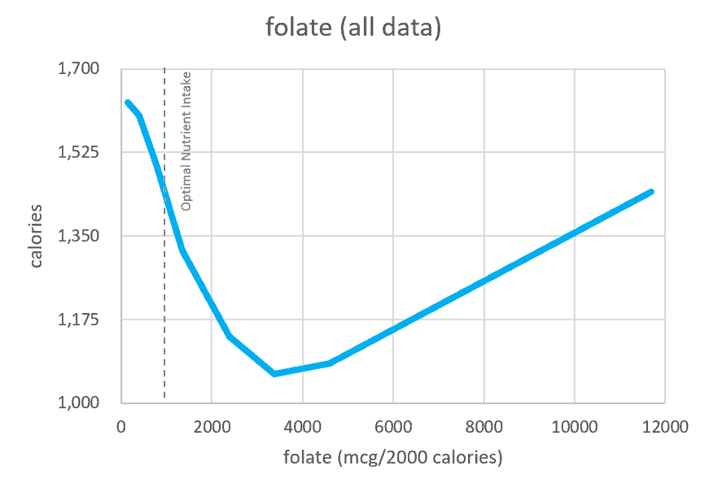

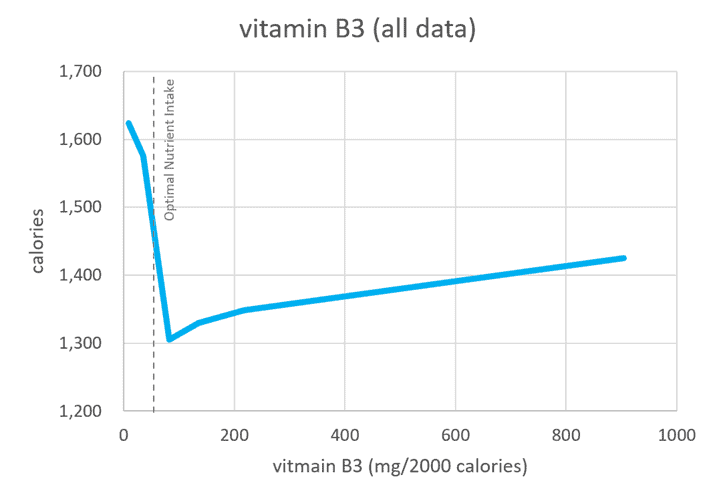

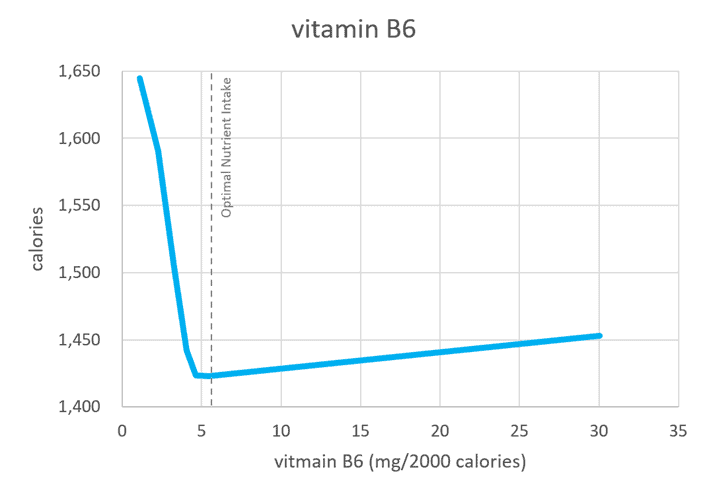

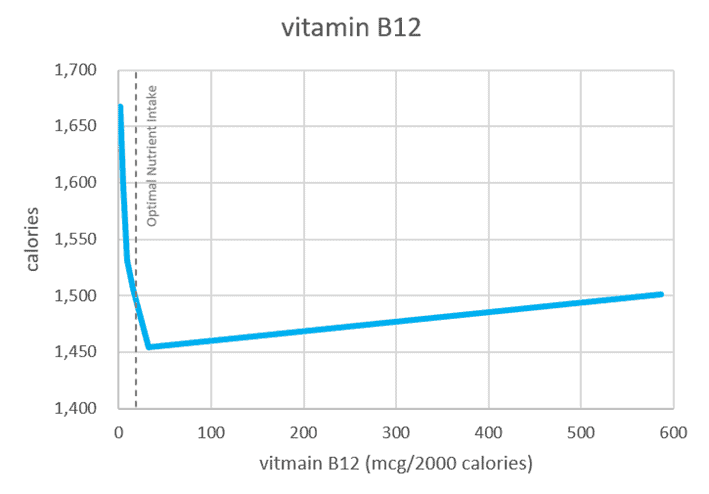

Our detailed satiety analysis has enabled us to identify an Optimal Nutrient Intake for each essential nutrient that can be entirely obtained from food without having to use supplements. These Optimal Nutrient Intakes (or ONIs for short) have been set based on the 85th percentile intake of each essential nutrient or the point at which the satiety response tapers off (whichever is the lesser).

So, although these Optimal Nutrient Intakes are challenging, it is perfectly possible to achieve them from whole foods that will provide you with a complete profile of synergistic nutrients.

Once we get enough of each nutrient from foods, our appetite settles down—at least for food that contains more of that particular nutrient. Subsequently, our appetite sends us in search of foods and meals containing other high-priority nutrients we will still need more of.

What Happens When We Consume Too Much a Nutrient?

As you will see, we often see a ‘rebound satiety response’ when we consume large amounts of nutrients that whole foods cannot provide. The analysis also gives us a fascinating insight into what happens when we consume more essential nutrients than we require from sources like supplements and fortification.

To summarise our findings, you can’t expect to experience the same satiety response from simply adding handfuls of supplements as you will get from eating whole foods that naturally contain the nutrients in the forms and ratios your body understands, can absorb, and utilise.

As we’ll discuss later, supplements and fortification appear to confuse your healthy appetite signals. So, rather than seeking healthy foods that naturally contain the essential nutrients, you’ll be content with continuing to chow down on fortified junk foods.

What Nutrients Are Supplemented Most Frequently?

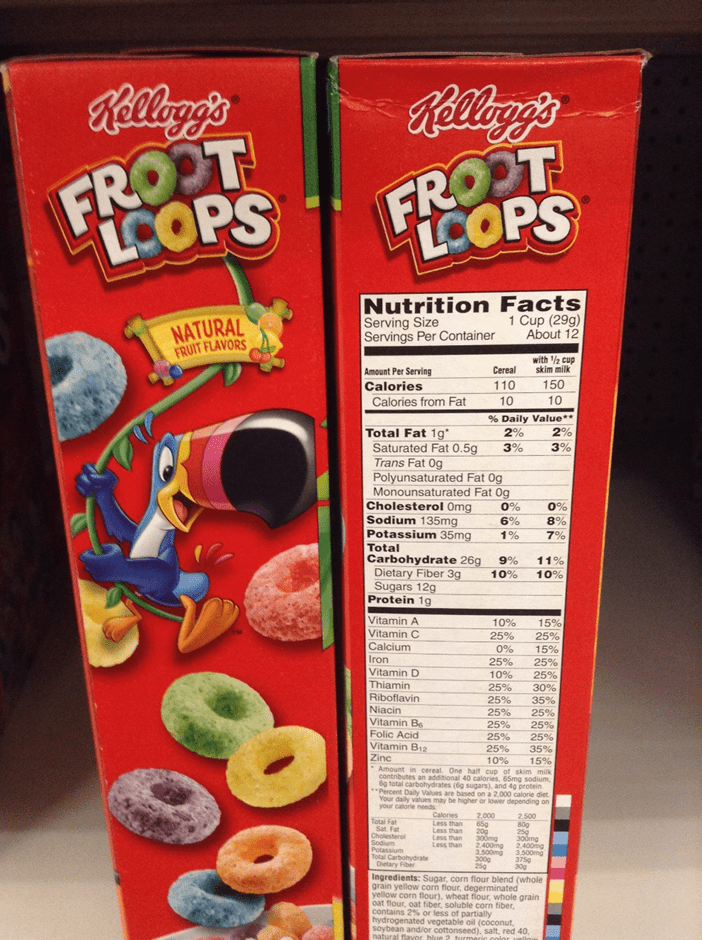

Because of size considerations and cost constraints, vitamins and micro minerals are the nutrients most frequently used to make supplements. Meanwhile, larger macro minerals like sodium, potassium, and calcium that tend to elicit the most significant satiety response are not commonly included in supplements or food fortification.

They just can’t fit enough of the macro minerals into your multivitamin or breakfast cereal. It would also be expensive. So smaller vitamins and microminerals are included in supplements and fortification while the larger macro minerals are neglected.

Vitamins

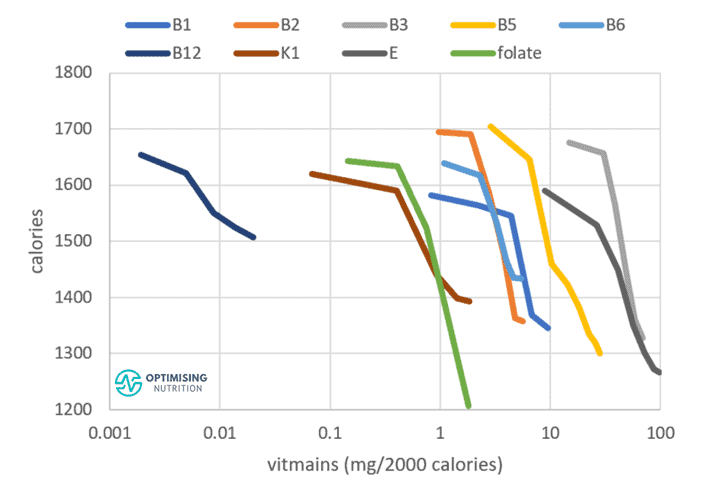

The absolute quantity of vitamins in our diet is tiny; we only require milligrams and micrograms of these nutrients. To illustrate, let’s take a quick look at the satiety response curves to show how they compare in terms of quantity needed.

To the right of the following chart, we see that we consume the largest absolute quantities of B3 (niacin) and vitamin E, despite ingesting less than 100 mg of each per day.

In contrast, vitamins like B12, folate, and K1 that we require in smaller amounts are shown toward the left of the graph. These nutrients are measured in micrograms, which are 1/1000 of a milligram!

As you can now see, it’s cheap and easy to fortify processed foods or produce multivitamin pills that people can take as ‘nutritional insurance’, hoping to compensate for a poor diet. To make things even less expensive, cheaper forms of nutrients may be used to really make a profit.

When we look at all the nutrients together in the multivariate regression analysis, we see that we have a statistically significant satiety response to some vitamins like riboflavin (B2), folate and pantothenic acid (B5) more than others. However, the magnitude of effect is much smaller.

For more details, see The Cheat Codes for Nutrition for Optimal Satiety and Health.

Minerals

Your body uses minerals for many purposes, like making enzymes, keeping your bones, muscles, heart, immune system, and brain working properly, and ridding the body of harmful substances.

In contrast to vitamins, we need greater quantities of sizably larger nutrients like the macro minerals. For example, we can consume up to 10 grams of potassium or sodium daily! This is shown in the chart below.

If someone were to rely solely on fortification to achieve daily mineral requirements, this would require a substantial volume of powders that couldn’t fit into fortified foods feasibly.

For example, you would have to consume 45 grams (about 1.5 oz) of our Optimised Electrolyte Mix recipe to hit the Optimal Nutrient Intakes for potassium, magnesium, and sodium! Substantial amounts of mineral powder tend to cause gut distress, so most people can only tolerate a little at once.

In the multivariate regression analysis, the larger macro minerals like potassium, calcium, and sodium typically absent in supplements and fortification always provide significant satiety responses. In contrast, we see a more minimal satiety response to the sizably smaller vitamins.

The table below shows the largest satiety response to a higher protein %. However, minerals like potassium, sodium and calcium still significantly impact our cravings and satiety.

| Nutrient | P-value | 15th | 85th | Calories | % |

| protein (%) | 0 | 19% | 44% | -486 | -31.6% |

| potassium | 2.18E-38 | 1931 | 5915 | -72 | -4.7% |

| fibre | 7.96E-48 | 11 | 44 | -70 | -4.5% |

| sodium | 1.14E-28 | 1480 | 5076 | -41 | -2.7% |

| calcium | 1.69E-17 | 469 | 1869 | -40 | -2.6% |

| pantothenic acid (B5) | 0.006 | 4 | 15 | -18 | -1.1% |

| folate | 0.22 | 167 | 956 | -7 | -0.4% |

| total | -47.6% |

Amino Acids

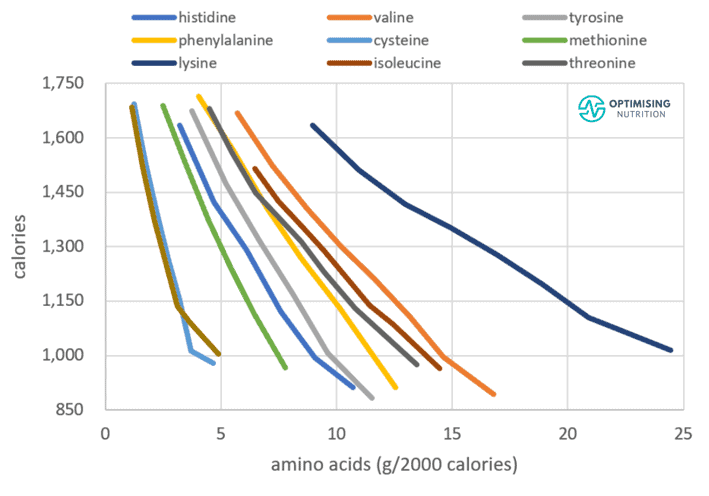

The amount of amino acids required is even more significant than vitamins and minerals! As you can see in the chart below, we can consume up to 25 grams of lysine per day. This is just one of nine essential amino acids!

While some people use protein powders and amino acid supplements like BCAAs, you have to go out of your way to do this. Thus, it’s much less frequent. It makes sense that protein, or the combination of all amino acids, has the greatest satiety response of any macro or micronutrients!

Nutrients That Have Decreased While Obesity Has Increased

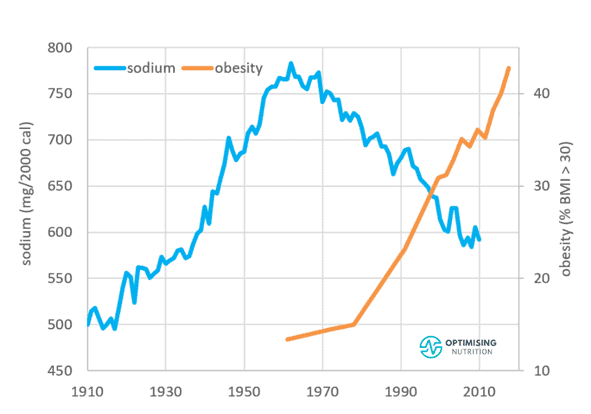

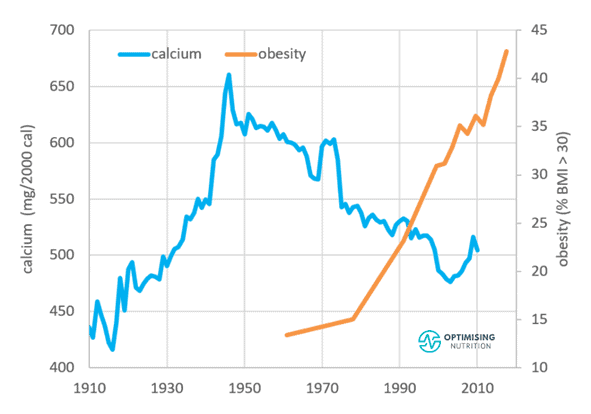

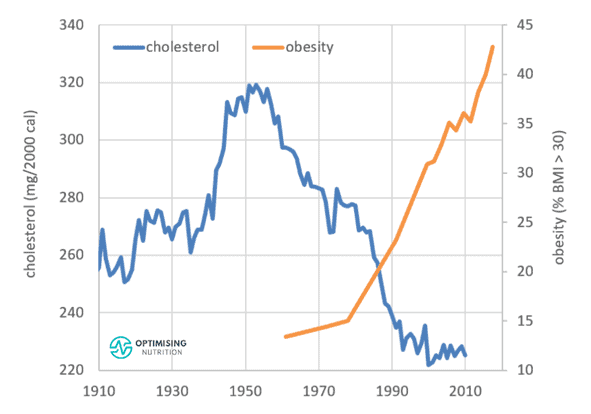

The table below shows the nutrients declining in our food system since the 1960s and their correlation with rising obesity rates.

| Nutrient | Correlation with Obesity |

| sodium | -96% |

| calcium | -96% |

| cholesterol | -96% |

| saturated fat | -92% |

| potassium | -91% |

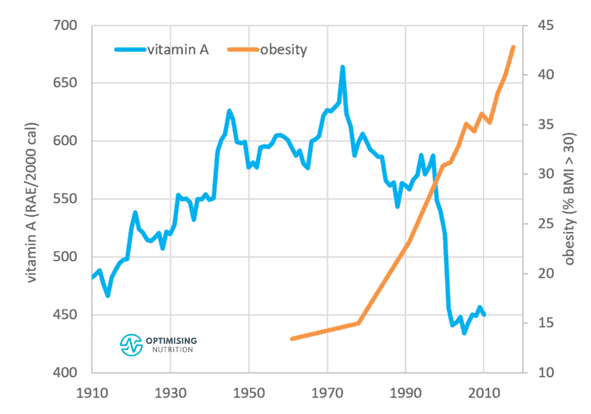

| vitamin A | -81% |

| phosphorus | -80% |

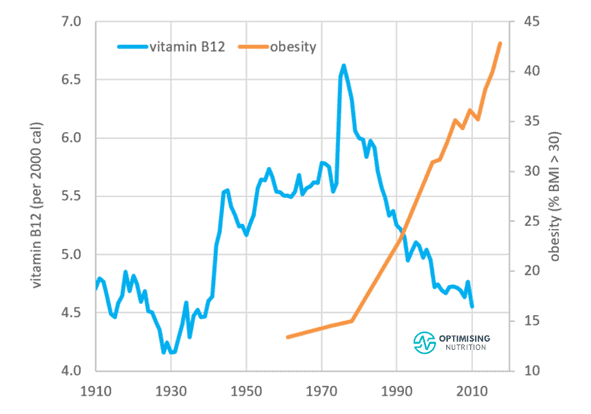

| vitamin B12 | -70% |

| magnesium | -33% |

| vitamin C | -3.4% |

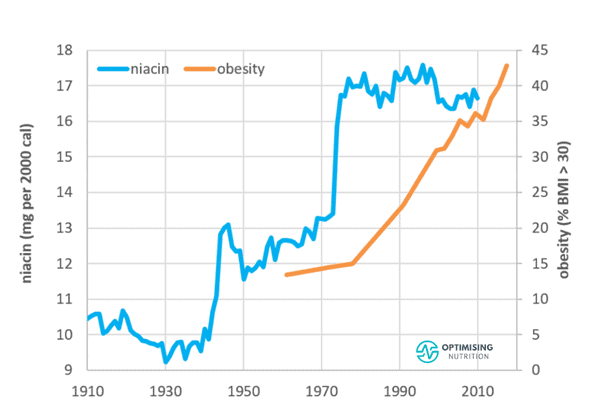

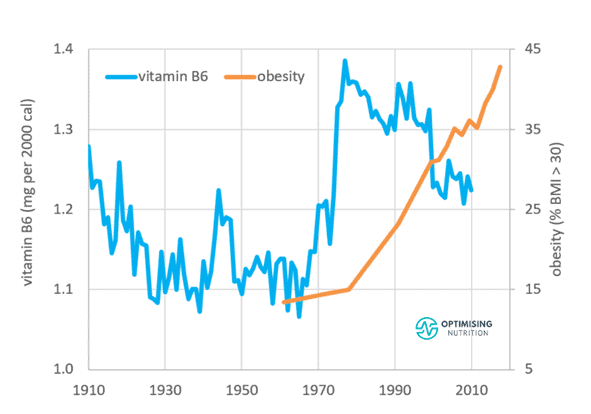

The charts below show the change in availability of various nutrients over the past century using data from the USDA’s Economic Research Service. Interestingly, our analysis showed many of the nutrients that have decreased the most were shown to elicit some of the most potent satiety responses. It appears we have the strongest cravings for many of the nutrients we can no longer get from the foods available in our food system, including from supplements and fortification.

But what about other nutrients aside from the macrominerals?

Don’t we need them too?

If nutrient leverage is a thing, shouldn’t we crave those too?

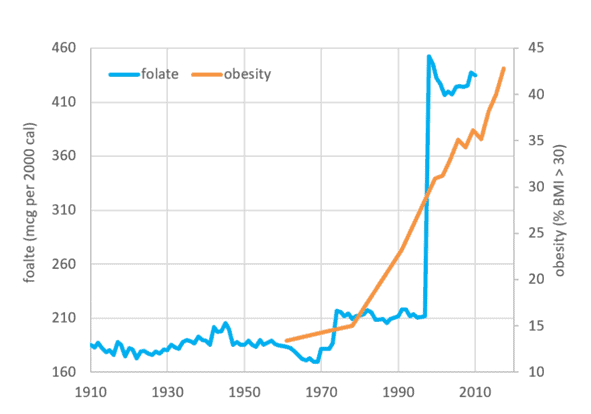

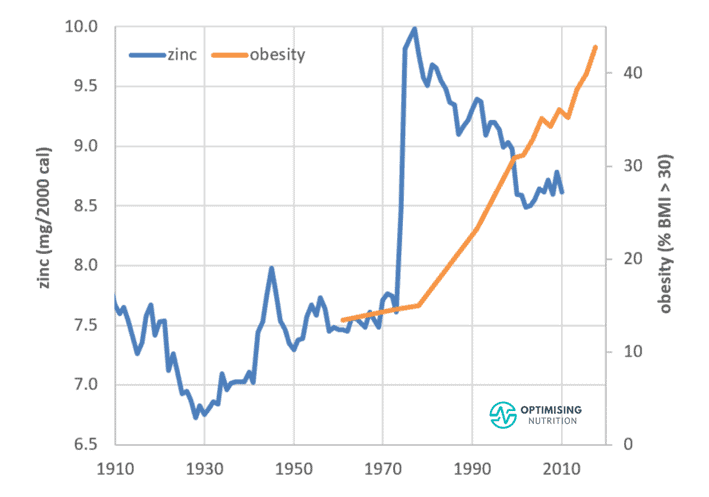

Nutrients that Correlate with Rising Obesity Rates

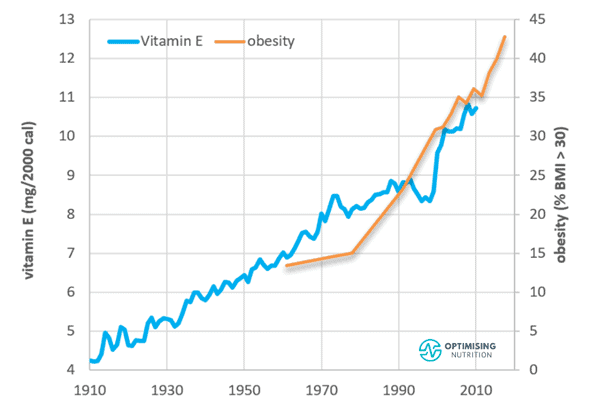

Many nutrients have declined in our food system because of degrading soil quality and the use of synthetic fertilisers to grow crops and animals rapidly. Thus, it would probably make sense that intakes of several of these nutrients are positively correlated with obesity rates that have steadily increased since the 1960s.

The table below shows some nutrients that have increased within our food system over the last sixty years. These influxes of nutrients also happen to correlate positively with the increase in obesity.

| Nutrient | Correlation with Obesity |

| folate | 96% |

| vitamin E | 91% |

| iron | 82% |

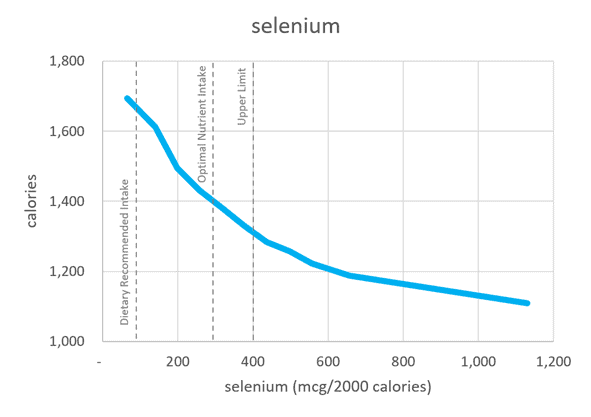

| selenium | 81% |

| thiamine (B1) | 66% |

| niacin (B3) | 44% |

| zinc | 20% |

| copper | 12% |

| vitamin B6 | 1% |

When we dig a little deeper, we find that the increase in these nutrients is due to widespread and sometimes even mandatory fortification programs. Food manufacturers realised that our food system had become so deficient that we had to fortify it out of public health concern! They now proudly brag on the packaging about the essential nutrients that ultra-processed foods contain, but only from the addition of synthetic fortification!

But now, as you’ll see in the following sections, there are many nutrients we may be getting too much of, meaning there can be ‘too much of a good thing’.

Nutrients that We See a Rebound Satiety Response To

The following section will examine the nutrients that elicit a rebound satiety response. In other words, very high intakes only achievable through supplementation or fortification tends to align with lesser satiety and a greater calorie intake.

We’ll also look at the role of fortification in our food system, for better and worse.

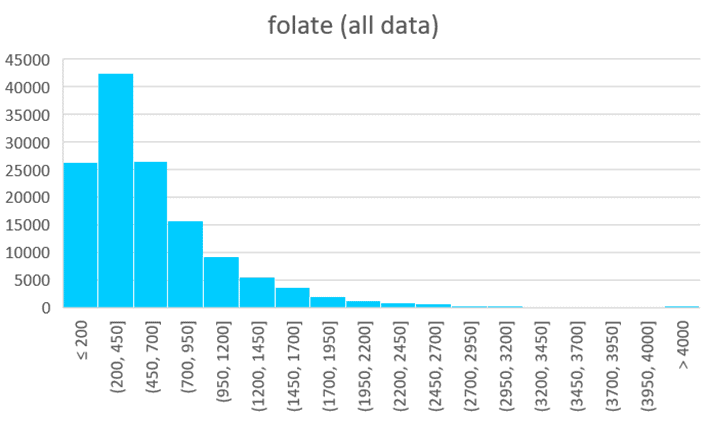

Folate (B9)

The word folate comes from the same Latin root word as foliage. Hence, it makes sense that we get most of our folate from green and leafy things. Given this fact, it’s probably not surprising that most people don’t get much folate these days!

We created the chart below using population intake data from the USDA Economic Research Service. Here, we can see that folate availability in the food system doubled in 1998 after folic acid fortification was mandated to prevent neural tube defects due to the deficiencies caused by high intakes of ultra-processed foods.

Before this time, the average population intake consumed around half the DRI of 400 mcg per day. The DRI is the intake estimated to prevent diseases associated with folate deficiency in 97.5% of the population (two standard deviations). The average intake is also much less than our folate ONI of 1000 mcg/2000 calories, which is also the tolerable upper limit from supplementation.

The median Optimiser folate intake is 444 mcg per 2000 calories, but some people are getting more than 4000 mcg per 2000 calories as shown in the distribution chart below.

Our satiety response curve shows that although it’s possible to get more folate from ultra-processed foods, people consuming these very high intakes of folate do not see the same satiety response as those obtaining moderate amounts from whole foods. So, more folate is not better once someone exceeds around 4000 mcg folate/2000 calories.

While there is no upper limit for folate in food, excess folic acid supplementation can mask a B12 deficiency (the converse is also true; excessive B12 supplementation can mask a folate deficiency).

Because of the synergistic effects of B12 and folate, large doses of folic acid consumed by an individual with an undiagnosed vitamin B12 deficiency could correct megaloblastic anaemia resulting from the lack of B12. However, it would not correct the underlying vitamin B12 deficiency, which could put the individual at risk of developing irreversible neurologic damage.

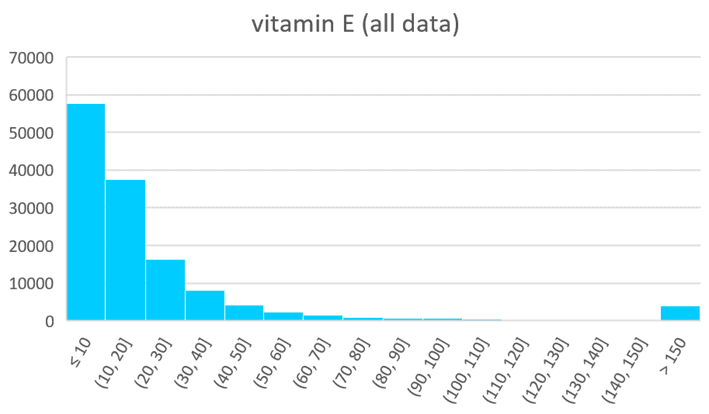

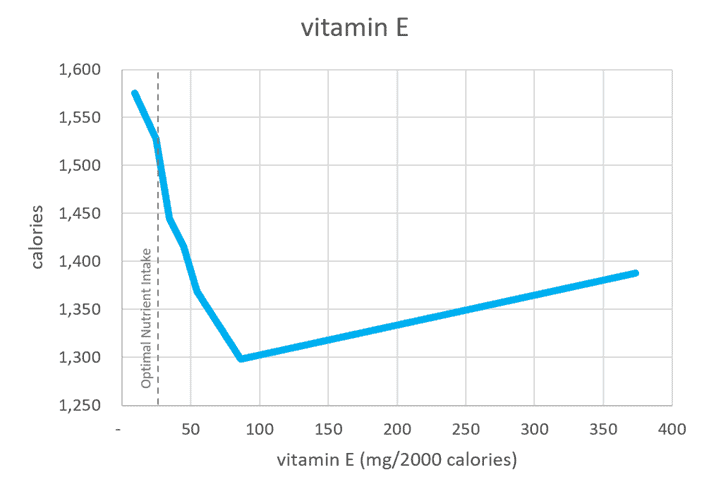

Vitamin E

Vitamin E has risen in parallel with the increased use of plant oils. Hydrogenation, or the process we use to isolate these seed oils from crops high in vitamin E, has fuelled the industrialisation of our food system.

The chart below shows that a significant amount of people exceed the ONI for vitamin E of 25 mg/2000 calories. Some are even getting more than 150 mg/2000 calories!

Whole foods like asparagus, broccoli, almonds, other nuts, and kale that naturally contain more vitamin E per calorie tend to align with a lowered caloric intake. However, people consuming more than 80 mg per 2000 calories of vitamin E from supplements or industrial seed oils tend to consume more calories per day.

It’s also worth noting that the majority of the vitamin E found in these processed seed oils is not in a form that is very bioavailable to the body.

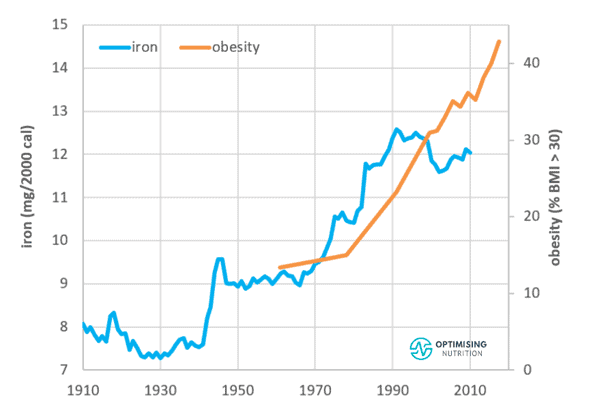

Iron

In the 1940s, iron fortification of enriched grains was mandated to combat the anaemia epidemic. Since then, iron availability in the food system has increased substantially.

Many people—like menstruating women—are at a high risk of iron deficiency. However, many take supplemental iron, overconsuming iron, and high iron levels (i.e., haemochromatosis) also can have negative health implications.

The body is highly efficient at recycling iron, making it difficult to eliminate once it builds up to toxic levels. While many try to limit meat to reduce their iron intake by avoiding animal-based foods, fortified foods like enriched grains may be a better place to start.

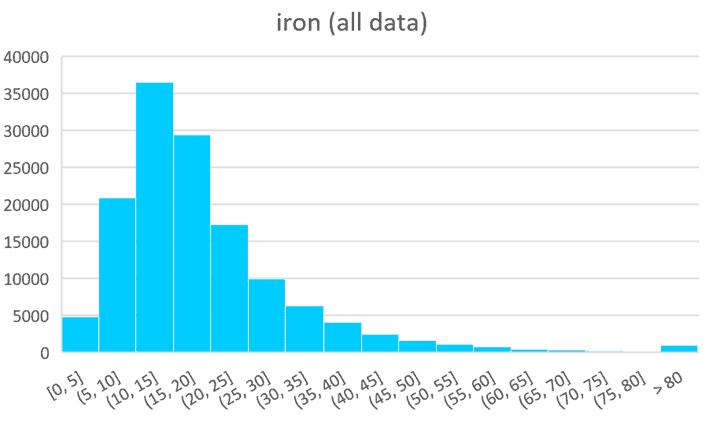

The median iron intake of our Optimiser data is 16 mg/2000 calories, which is less than the ONI of 30 mg/2000 calories. However, we can see that a small subset is getting more than 80 mg/2000 calories, likely from fortified foods or supplementation.

When we look at our satiety response to iron, we see a rebound satiety effect once we exceed around 80 mg/2000 calories.

While foods like liver, egg, beef, and vegetables that contain more iron per calorie and consuming more of them aligns with a lower calorie intake, fortification of grains or supplemental iron does not appear to have the same effects on satiety.

Thiamine (B1)

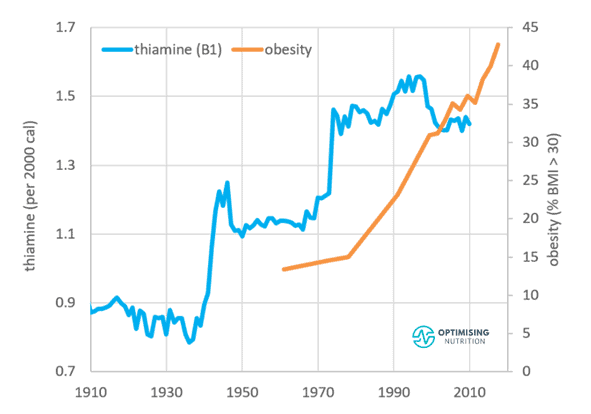

Thiamine (or vitamin B1) is a member of the B vitamin family. Thiamine deficiency results in a condition known as beriberi. Thiamine was the first B vitamin to be isolated in 1926 and manufactured synthetically in 1936. In 1939, the fortification of grain products with thiamine began to combat beriberi.

Since the 1940s, there has been a significant increase in thiamine availability in the food system. A further update of nutrient fortification standards for breakfast cereals was introduced in 1974, accounting for the second rise of thiamine shown in the graph below.

The 2014 paper, Excess vitamin intake: An unrecognised risk factor for obesity, highlights the sharp increases in infant formula and breakfast cereal fortification that correlate with sharply increasing obesity rates when it was introduced in different countries.

Because B vitamins help us access the energy in our foods, the study notes that B vitamins also promote fat synthesis. This is especially true when found synthetically in high-glycaemic foods like fortified bread, pastries, and cereals rather than meat, seafood, and vegetables.

These foods may also cause some form of hypoglycaemia (i.e., low blood sugars) in the hours after they are consumed, which can compound our increased appetite for high-glycemic, fortified foods.

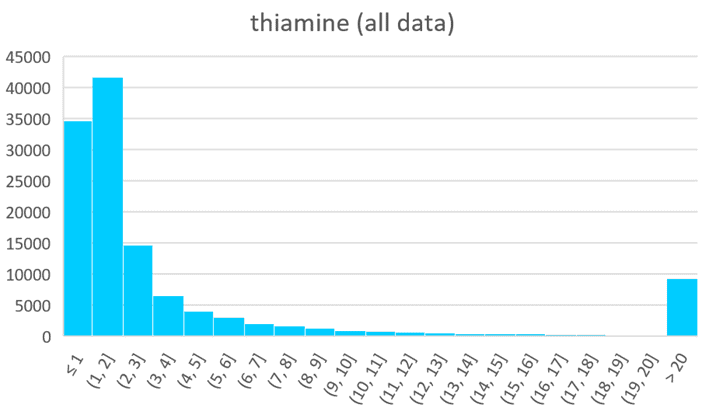

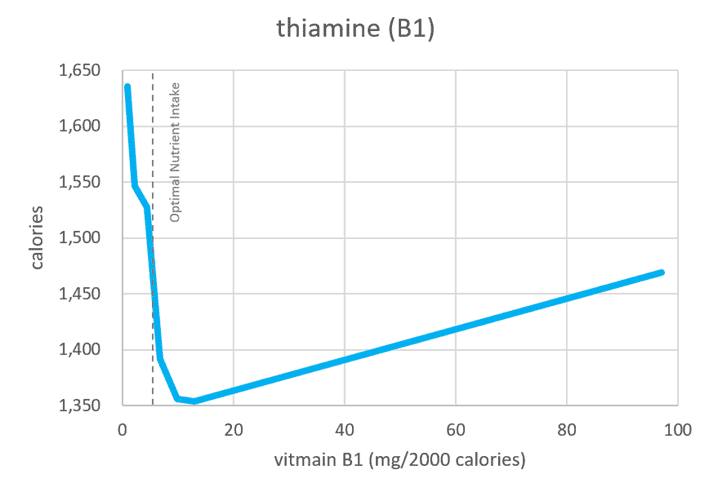

While we set our ONI for B1 at 3 mg/2000, the chart below shows that many Optimisers get more than 20 mg/2000 calories of vitamin B1.

When we look at the satiety response to thiamine, we see a significant rebound satiety effect when we consume more than 10 mg of B1/2000 calories. Hence, multivitamins and fortified foods that contain B1 do not improve satiety.

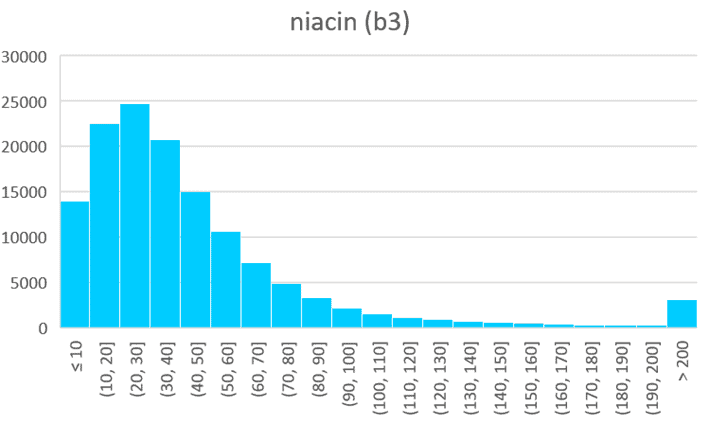

Niacin (B3)

Niacin (vitamin B3) availability follows a similar trajectory to thiamine. Since fortification was introduced in the 1930s, vitamin B3 levels have increased markedly in the food system. In 1974, similar to thiamine, when cereal fortification guidelines were revised.

The median niacin intake of our Optimiser data is 33 mg/2000 calories. However, many people consume well beyond 200 mg niacin/2000 calories.

The satiety response curve for niacin shows how intake levels exceeding what whole foods like vegetables and meat naturally provide elicit a rebound satiety effect.

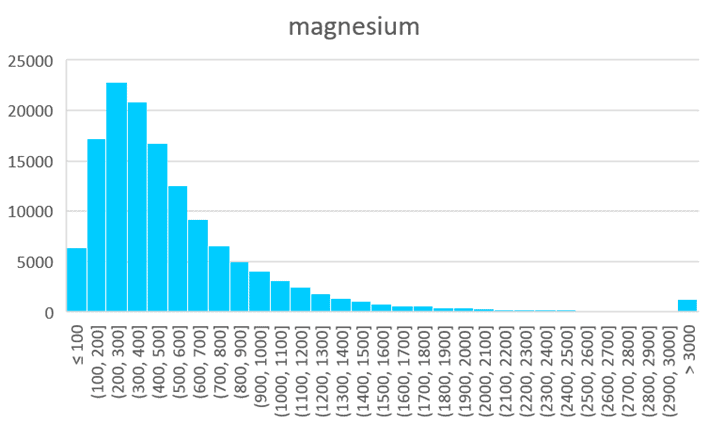

Magnesium

Magnesium is an essential macro mineral involved in thousands of bodily functions and enzymatic reactions. For this reason, it is frequently supplemented. However, most people find it hard to over-supplement magnesium because of its laxative effect.

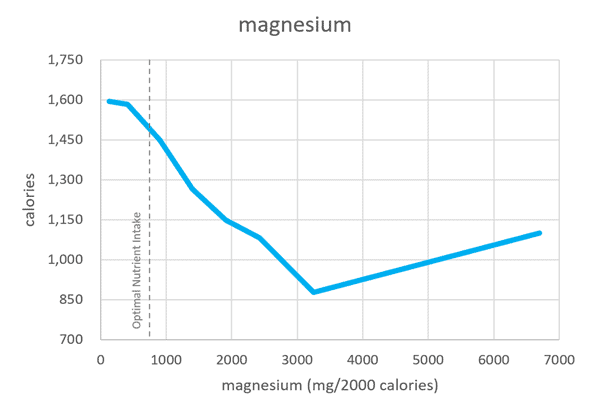

The median magnesium intake of our Optimisers is 400 mg/2000 calories, but we can see that some people get more than 3000 mg/2000 calories. Using this information and the data from our satiety analysis, we have set our ONI to 825 mg/2000 calories.

Again, we see a rebound satiety response when we exceed 3000 mg/2000 calories of magnesium.

Zinc

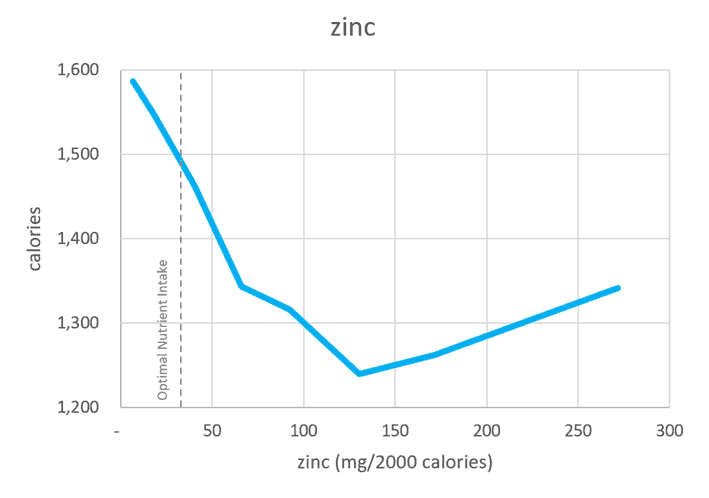

While seafood, meat, dairy, and vegetables are good sources of zinc, fortified breakfast cereals became another significant source when we began fortifying them with zinc during the 1970s.

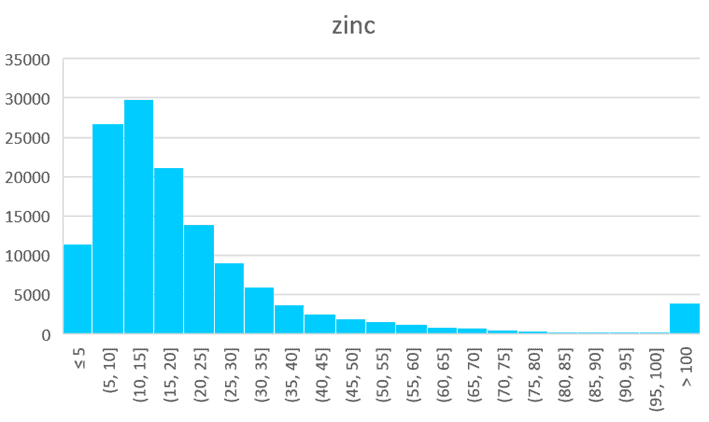

The median zinc intake of our Optimisers is 15 mg/2000 calories, which is far less than the ONI of 30 mg/2000 calories. However, many people get more than 100 mg/2000 calories due to supplementation and fortification.

Again, we see a rebound satiety response when supplementing above 130 mg/2000 calories.

Copper

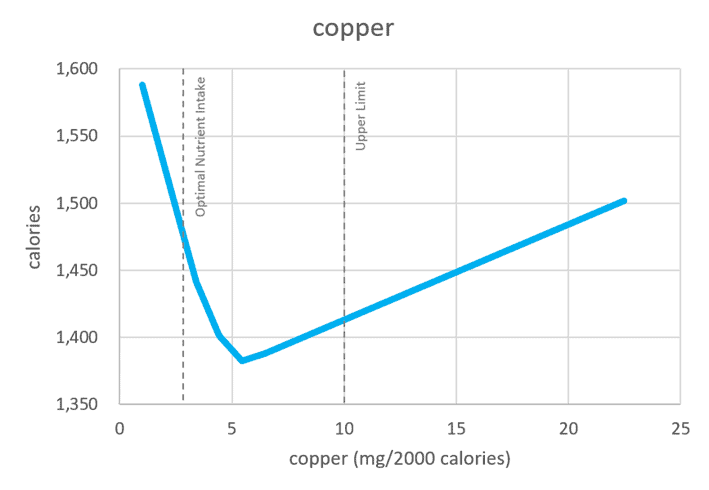

While not typical, it is possible to overconsume copper from whole foods like organ meats and develop conditions associated with toxicity. Excess copper can imbalance your copper:zinc and copper:iron ratios and deplete levels of these synergists over time. However, this should not be a cause of concern if you regularly consume proportional amounts of zinc and iron from whole foods and do not eat kilos of liver per day!

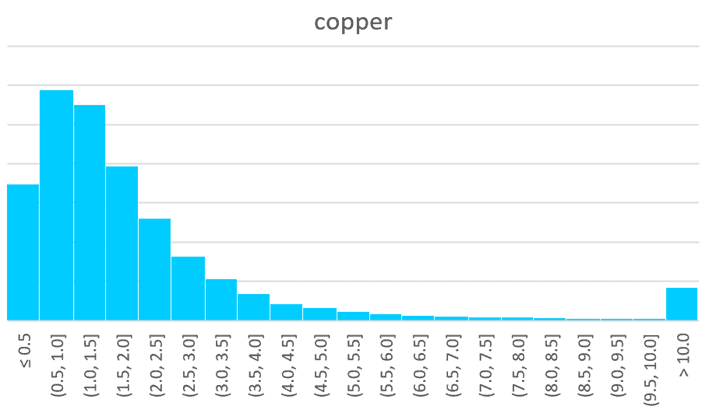

The median copper intake of our Optimisers is 1.4 mg/2000 calories, and our ONI is 3.0 mg/2000 calories. However, many people are getting more than 10 mg/2000 calories!

The satiety response curve also shows a distinct rebound satiety effect once we exceed around 5.5 mg/2000 calories of copper.

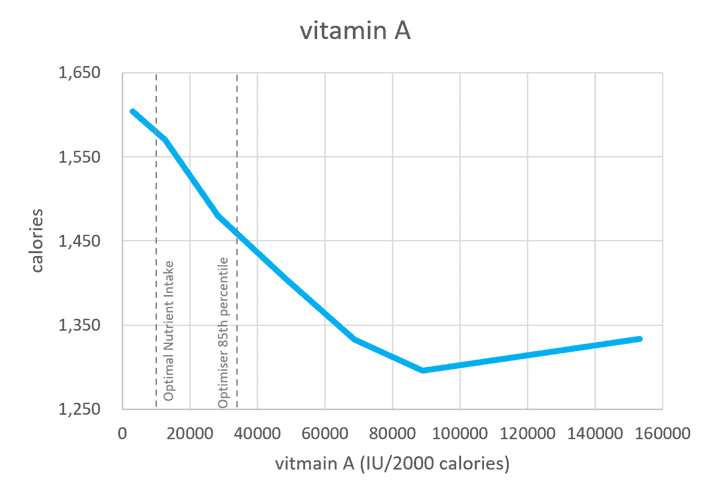

Vitamin A

Without fortification, the US intake of vitamin A has plummeted since the 1970s. Vitamin A is found readily in foods containing cholesterol and saturated fat, like liver, egg yolks, and butter, in its bioavailable retinol form. The 1977 Dietary Goals for Americans substantially limited these nutrients, which had inadvertent effects on vitamin A intake.

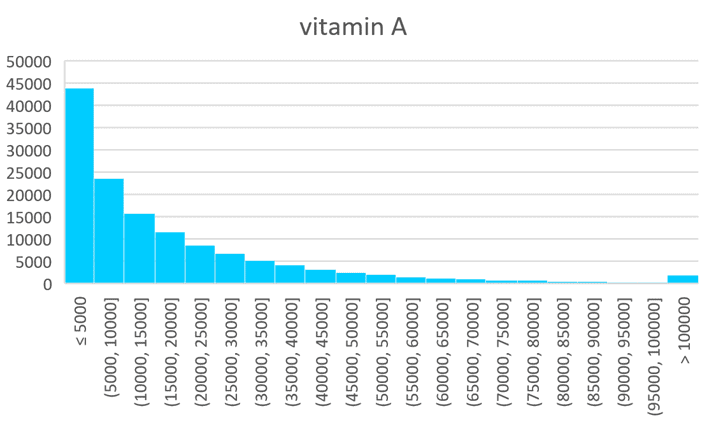

Vitamin A is one nutrient where the RDA of 900 micrograms appears to be extremely low. In comparison, the median intake of our Optimisers sits right around 10,162 micrograms/2000 calories, which is similar to the Upper Limit of 10,000 micrograms.

The 85th percentile intake of Optimisers is 35,278 micrograms per 2000 calories. The distribution chart for vitamin A shows that some people even exceed more than 100,000 micrograms per 2000 calories from a lot of organ meats or (and) supplementation.

The satiety response curve shows that we have a positive satiety response to vitamin A up until around 90 mg/2000 calories. At that point, we see a slight rebound.

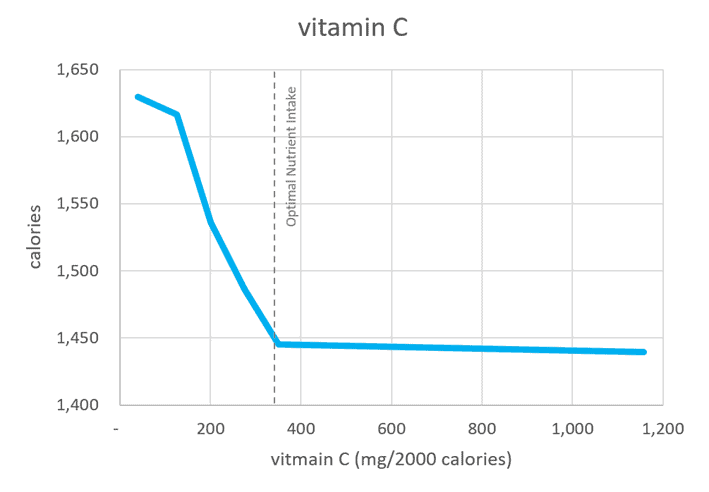

Vitamin C

Vitamin C is commonly supplemented and used as an antioxidant and anti-browning agent in processed and preserved foods.

While the median intake is only 150 mg/2000 calories and our ONI is 350 mg/2000 calories, the distribution chart below shows that many consume well beyond 2000 mg/2000 calories, likely from supplements.

However, there doesn’t appear to be much benefit in consuming more than 350 mg/2000 calories of vitamin C, at least from a satiety perspective.

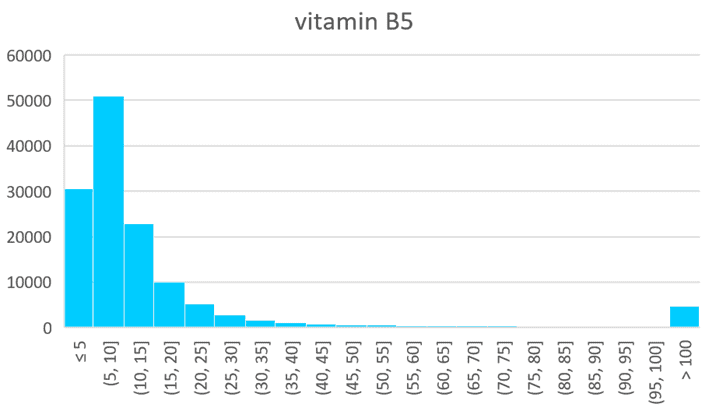

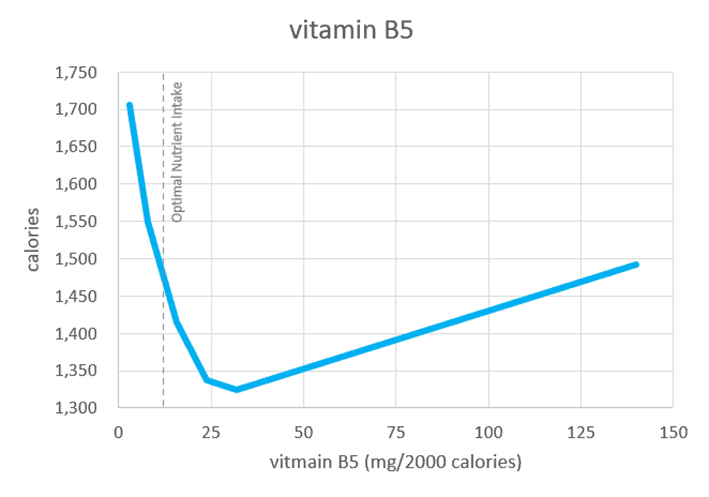

Vitamin B5

Although ‘panto’ means ‘in everything’, pantothenic acid (B5) is a nutrient commonly used in supplements and fortification. The median Optimiser intake is 8 mg/2000 calories, and the ONI is 12 mg/2000 calories. However, many people consume well beyond 100 mg/2000 calories from synthetic sources.

Consuming more B5 beyond 30 grams/2000 calories aligns with a greater energy intake, demonstrating that supplements and fortification do not increase satiety.

Vitamin B6

Like many other nutrients mentioned above, the US intake of vitamin B6 jumped in the 1970s when fortification increased.

While the median intake of vitamin B6 from our Optimiser data is 2.9 mg/2000, many people are getting more than 40 mg/2000 calories.

Again, more vitamin B6 beyond the ONI of 6 mg/2000 calories doesn’t necessarily align with greater satiety.

B12

Many people supplement with B12, especially if they follow a plant-based diet. We can see that the US intake of B12 has dropped since the Dietary Guidelines for Americans encouraged people to avoid saturated fat and cholesterol, which happens to be in many high-B12 animal foods like meat, poultry, and seafood.

While the median B12 intake is nine mcg/2000 calories, many people log more than 100 mcg/2000 calories.

However, we see a rebound satiety response with intakes exceeding intakes achievable from an omnivorous whole foods diet.

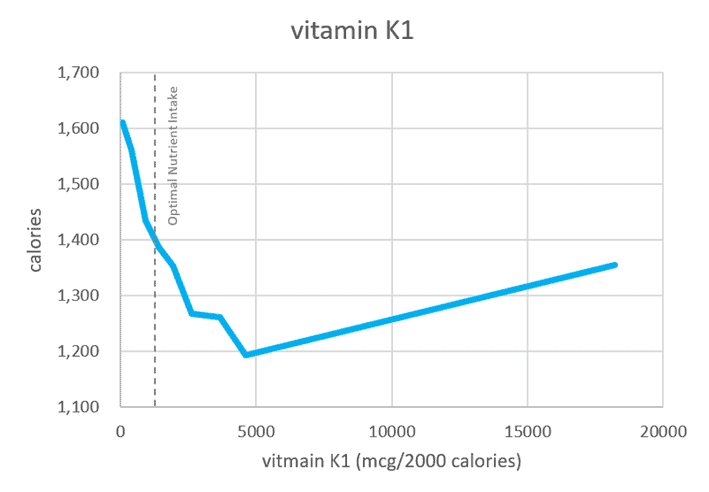

Vitamin K1

Vitamin K1 is not typically used in food fortification. However, it is sometimes supplemented.

The median K1 intake of our Optimiser data is 262 mcg/2000 calories. In comparison, the ONI for vitamin K1 ONI is 1100 mcg/200 calories, and the DRI is 90 mcg/2000 calories. Although there is no tolerable upper limit (UL) set for vitamin K1, and we only see a tiny portion of the population supplementing with large amounts of it, excessive supplementation has been known to cause blood clots.

When our K1 intake exceeds 5000 mcg/2000 calories from supplementation, we tend to see a rebound satiety response.

Pros and Cons of Fortification

We see a substantial decrease in energy intake when we increase our consumption of most nutrients from whole foods. However, substantial nutrient intakes only achievable through supplementation and fortification tend to lead to a rebound satiety response. If your body already has plenty of a certain nutrient, consuming more of that same vitamin, mineral, essential fatty acid, or amino acid will not provide greater satiety.

Nutrient leverage occurs when nutrients come in food rather than pill, powders, and fortification.

Additionally, we must consume the effects that high supplementation of one nutrient has on others. Because vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids, and amino acids work synergistically AND antagonistically with one another, taking in too much of one from fortification or supplementation could increase our demands for another.

For example, magnesium and calcium are antagonists of one another, and the estimated calcium:magnesium ratio is 2:1. Hence, taking a substantial amount of magnesium will proportionally increase your demand for calcium to scale.

Not all fortification and supplementation are bad; fortification and supplementation can be beneficial for frank deficiencies or when nutrient-dense foods are hard to obtain. For example, fortification has undoubtedly been helpful by providing folic acid to mitigate neural tube defects, vitamin B1 to prevent beriberi, and vitamin B3 to minimise pellagra in a nutrient-poor food environment that has resulted from modern farming and food manufacturing processes.

However, our data analysis suggests that supplementation and fortification of isolated nutrients in levels over and above what is naturally found in whole foods do not correlate with an overall lowered calorie intake.

Why Is There a Greater Calorie Intake with Supplementation and Fortification?

The increased calorie intake seen with very high nutrient intake levels only achievable from supplementation or fortification may be because:

- Isolated synthetic supplements do not provide the same satiety benefit as whole foods, which provide nutrients in the forms and ratios that the body understands, and (or)

- There is an increased craving for fortified foods because of their palatability or because of the synthetic nutrients they contain, but they do not provide the same satiety that we would see from nutrients in whole foods.

Research by Dana Small suggests that foods providing nutrients that do not align with their taste sends the brain into a more risk-averse behaviour.

Rather than trusting the food environment to provide nutrients reliably in-line with taste sensations, your appetite will increase to ensure adequate energy and micronutrients are obtained in an uncertain environment. Thus, ultra-processed foods and fortification may increase hunger and overconsumption beyond our biological requirements.

We’re Being Fed Fortified Pig Slop!

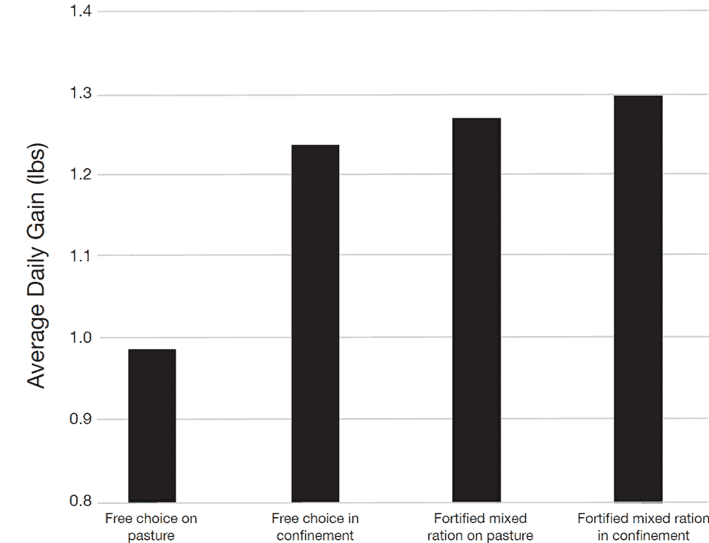

In 1959 the University of Illinois produced a landmark pamphlet titled Balancing Swine Rations, which documented their research that identified the feeding regime that optimised growth and minimised the feed ratio (i.e., maximum weight gain with minimal food and financial inputs to optimise profit).

Before vitamin supplementation, farmers had to ensure that their pigs had time on pasture or were fed alfalfa to obtain adequate vitamins so they could grow and remain healthy. They also found that pigs would predominantly choose pasture and unfortified feed if given a choice between it and fortified feed.

Farmers had observed that pigs housed in barns fed solely on grain and corn would get sick, lose their hair, and fail to thrive. However, pigs in enclosures fed only fortified feed without an alternative not only maintained a general bill of health, but they also gained weight the quickest at the lowest cost. Rather than seeking pasture or consuming alfalfa, they ate more of the cheap fortified feed.

In his book, The End of Craving, Mark Schatzker likens our modern food system to the fortified pig food designed to maximise growth while preventing deficiencies. It appears that the fortification of ultra-processed food overrides our innate drive to seek out a variety of foods that contain the full spectrum of nutrients we need to thrive so we can avoid excessive calorie intake.

Since 1959, this understanding of the role of supplementation has been used heavily in the livestock industry to maximise growth rates for meat production. The increased rates of fortification of breakfast cereals and other ultra-processed foods that occurred shortly after may have inadvertently (or perhaps intentionally?) had a similar impact.

Because ultra-processed foods now contain more nutrients we require to thrive, we are content to continue eating more of them. Unfortunately, as a result, we have a reduced appetite for food that naturally contains the nutrients that are commonly fortified.

Rather than craving vegetables, meat, and seafood, we’re more likely to be content chowing down on our heavily fortified, flavoured, and coloured breakfast cereals. Ironically, they would taste blander than the box without the extra help from the added flavours, sugars, and fortification!

In summary, we can only assume the positive impact on satiety from improving your nutrient density comes from eating whole foods that supply a broad range of essential and non-essential nutrients. Isolated synthetic nutrients found in nutritional supplements and fortification do NOT have the same influence.

Our analysis shows that we have statistically significant cravings for not just protein but many of the essential nutrients.

Hence, fortification may increase our cravings for ultra-processed foods that drown out cravings for whole foods that contain all the essential nutrients we need to thrive.

Supplementation and fortification of high doses of isolated synthetic nutrients is a bit like playing God in a game that we don’t understand all the rules.

Could Supplements and Fortification be Bad for You?

Targeted supplementation may be appropriate for someone who cannot consistently meet the DRIs and AIs for specific nutrients.

However, these levels are easily achieved by intentionally and intelligently focusing on foods that contain more of the nutrients someone needs to prioritise. This is because nutrients are synergistic with one another, and they often come packaged as an entire complex in whole foods. Additionally, they are in the most bioavailable form.

In contrast, supplements use concentrated synthetic forms of nutrients in formats and ratios unnatural to the body. Hence, supplements will not likely provide the same satiety benefit as nutrient-dense whole foods.

Not only can fortification imbalance nutrient ratios, but it may also skew cravings for foods naturally containing nutrients someone should prioritise. This could negatively impact satiety by increasing cravings for nutrient-poor fortified foods, albeit the narrow band of nutrients they’re enriched with.

Finally, the absorption and bioavailability of synthetic vitamins and minerals have also been questioned. For example, studies looking at bioavailability rates of synthetic vitamins like thiamine hydrochloride are as low as 3.7 to 5.3%.

Additionally, many forms used for fortification may require additional steps to be activated and usable by the body for biological processes. Genetic and epigenetic factors can also influence how readily available certain synthetic forms can be absorbed and utilised by the body.

Should You Take Supplements?

Supplements and fortification certainly have a role if you have a diagnosed medical deficiency. Additionally, a supplement—under the direction of a health professional—may be helpful if you consume a limited diet and repeatedly fall short of the minimum nutrient intake targets.

However, higher nutrient intakes from supplementation in the absence of a diagnosed deficiency don’t appear to provide anything other than a false sense of security and make you feel as if you do not need to put as much effort into dialling in your nutrient intake.

In our Micros Masterclass, we guide people through reducing their use of supplements and fortified foods once they can meet the DRI or AI for that nutrient with whole foods alone. Once you know you’re getting nutrients from food, they’re a waste of money and headspace.

In our Micros Masterclass, we use Nutrient Optimiser to systematically review your current diet so you can determine any significant nutrition gaps and identify the foods and meals that will provide them effectively for the fewest calories.

Rather than relying on expensive testing that is often inaccurate, the best way to identify which nutrients you require is to track your diet for several days.

To find your priority nutrients and the foods that contain them, you can take our free 7-Day Nutrient Clarity Challenge.

Summary

Our satiety analysis of one hundred and fifty thousand days of nutrient data from forty thousand people shows that we have a distinct satiety response to all the essential nutrients in food. However, we do not see this same response when we consume high intakes of nutrients that only supplements and fortification can provide.

While supplements and fortification can undoubtedly be beneficial when someone has a legitimate deficiency, it appears that mismatching nutrients in regularly nutrient-poor foods they don’t belong in could:

- Confuse our appetite and lead us to eat more and

- Keep us eating low-satiety, ultra-processed foods rather than listening to our innate cravings for whole foods that naturally contain nutrients.

Rather than relying on supplements and fortification, Nutritional Optimisation enables us to identify foods that contain the nutrients we require to maximise satiety and thrive.

The term “pig slop” is what I refer to when noticing shoppers’ carts as they check out and exit warehouse stores–large quantities of packaged junk foods with little to no nutrient value, and this is why I no longer belong as a member to any of those “farms” in spite of the fact that the per-unit prices are lower than what you’d see at a regular grocery store. Sure, the price per unit may be smaller, but the membership price, the packaging disposal cost, and the healthcare costs incurred to resolve nutrient deficiencies make up the difference. It’s a shame more people aren’t seeing this for themselves. The keto diet is what opened my eyes so many years ago. I lost weight, but gained so much insight into actually feeding my body correctly (as well as cupboard space, refrigerator space, and most importantly, time).

Then there’s the regular grocery stores during the first nine days of every month–also known as SNAP (food stamps) season. This is just a miniature version of what goes on at warehouse stores, with 6-packs of soda, a box of assorted lunch-box-sixed chips, doughnuts, boxes of rice and pasta, boxes of cereal, gallons of ice cream, sugary yogurt, and microwave meals… all of it on the taxpayers’ dime. While a government agency determines eligibility and allowance according to income and family size, SNAP pays for just about anything you can put in your mouth that isn’t heated. Are they worried about getting more nutrient bang for their buck? Nope–just about how full they can get the cart, and whether or not the junk IN it will last the entire month (because they tend to blow the entire allowance as soon as they get it). Church food banks fill in the holes later in the month. Satiety never even enters into the equation. The government agency that runs this program tries to educate people about the most effective ways to use food stamps: they have counselors, a website with printable brochures, and even a printable recipe book. Unfortunately, this seems to be all in vain–people on the food stamp program simply shop to feed their tongues and not their bodies or brains as the program intended (in other words, maximum convenience–no cooking beyond the microwave). I call this “slopping the hogs.” To avoid the onslaught of SNAP shoppers, I time my perishable forays around food stamp season just to be able to get both a parking spot and a cart. I find I’m not alone in this.

I once belonged to a warehouse store about a couple of decades ago just for non-perishables, but online shopping alleviates the view of all the overflowing carts of pure CRAP in the checkout lanes! Besides, diligent searching online can yield matching- or near-matching price savings without the cost of membership, having to drive across town just to get to the store, or jockeying for a parking spot once you get there, and sometimes even having to jockey for a shopping cart to use. Big tax refunds, big paydays, or a warehouse store that accepts SNAP payments usually mean a big shopping day, and people have been known to use more than one cart.

Sometimes I’ll see my neighbors backing their car into their driveway to more easily unload the boxes of soda, huge bags of chips, buckets of pre-barbequed pork pieces, and other village-sized portions of various junk foods from their trunk (the neighbors themselves are village-sized), and I comment to my husband that it must’ve been time to slop the hogs again. There’s just two of them–how much junk do they need? Apparently a lot…satiety and all that. Now it’s become a viewing ritual–whenever they back the car in, it means they went grocery shopping. It should be called “grossery shopping” because it’s gross to think what goes on over there in terms of health abuse.

I’ve also noticed that as far as packaging goes, what comes IN must also go OUT. Just one trash can won’t do for the consumption going on next door–they use 2 trash cans that get dumped weekly. Yes, they recycle, but it makes no difference. On occasion, they have plastic bags of excess trash out to the curb next to the cans. All that convenience packaging! I don’t think they realize all the costs associated with feeding their tongues.

Meanwhile, I tow my half-filled trash can to the curb every week to be dumped. Yes, I still cook from scratch. Yes, this means minimal processing, minimal packaging, minimal trash, and a much more adequate nutrient intake. We see a doctor once a year–that’s all that we need, and I read Marty’s website to learn all I can about health maintenance (been doing that for nearly a decade).

9/29/22 update: Now it seems we can blame our brains for obesity (or at least mice can)–https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/965474

Thank you for this great article Marty! I used to take soooo many supplements until I started your programs. Now I might even rethink those electrolytes I’m still drinking 3 to 4 times per week!