Embark on a transformative journey to unravel the enigma of insulin resistance and discover how to reverse it.

This comprehensive guide enlightens you on the core of insulin resistance, empowering you with the knowledge to identify, confront, and potentially reverse it naturally.

Dive into a realm where metabolic wellness is within reach, and join thousands who have successfully navigated the path to improved metabolic health?1?.

Join thousands who’ve transformed their metabolic health using these methods in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenge and Macros Masterclass.

- How Do I Know If I’m Insulin Resistant?

- What Happens When You Have Insulin Resistance?

- What Does Insulin Do in Your Body?

- What Would Happen If You Didn’t Have Enough Insulin?

- Does Insulin Make Me Fat?

- Reactive Hypoglycaemia

- Do Carbohydrates Cause Insulin Resistance?

- What Is the Best Way to Fix Insulin Resistance?

- Does Dietary Fat Cause Insulin Resistance?

- What Is the Main Cause of Insulin Resistance?

- What Causes Insulin Resistance?

- Your Veins Are Like a Hose…

- Can You Fix Your Insulin Resistance?

- What Is the Fastest Way to Reverse Insulin Resistance?

- How Can You Fix Your Insulin Resistance?

- More

How Do I Know If I’m Insulin Resistant?

With skyrocketing increases in obesity, diabetes, and conditions related to metabolic syndrome, you likely have some insulin resistance.

But insulin resistance is a symptom that is a key component of Type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome.’

As you will learn, insulin resistance isn’t an on/off switch. Instead, it’s a gradient from optimal metabolic health to extreme Type 2 diabetes.

Insulin resistance is fundamentally a condition where your body is trying to store more energy than it can comfortably or healthily handle.

People with insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes tend to have higher:

- body weight,

- blood glucose,

- waist circumference,

- blood pressure,

- cholesterol,

- HbA1c, and

- triglycerides.

While there are many tests that your doctor can do to confirm whether you are insulin resistant, a simple tape measure is perhaps the simplest and most effective. If your waist is more than half your height, you likely have some insulin resistance.

Your waist-to-height ratio is a super simple and cost-effective measure of your risk of dying of any cause!

If you want to dig in a little deeper to see where you fall on the insulin resistance–diabetes spectrum, you can check your blood sugar levels if you have a glucometer or continuous glucose meter.

See What Are Normal, Healthy, Non-Diabetic Blood Sugar Levels? for more detail on optimal blood glucose ranges.

What Happens When You Have Insulin Resistance?

Someone with insulin resistance is also more prone to many concerning health conditions related to poor metabolic health, including:

- depression,

- anxiety,

- cancer,

- cardiovascular disease,

- stroke,

- hormonal disruptions like loss of libido and poor fertility, and

- systemic inflammation.

Addressing insulin resistance becomes more critical.

What Does Insulin Do in Your Body?

Before we look at how to reverse insulin resistance, we must understand insulin’s role in your body. As you will see, insulin is critical for managing the dynamic energy flux in your blood at all times.

Insulin is a critical hormone produced by the beta cells of the pancreas to regulate the flow of fuel from storage to the rest of your body. Insulin ensures that your body has just enough energy in your bloodstream at any given time to fuel your day-to-day activities.

At any given time, you have only about 5 grams (20 calories worth) of glucose and 150 calories of fat buzzing around your bloodstream. So, as you burn it off, your body must continuously top up the energy it uses from storage reservoirs, like the liver—which stores glycogen—and adipose tissue—which stores body fat.

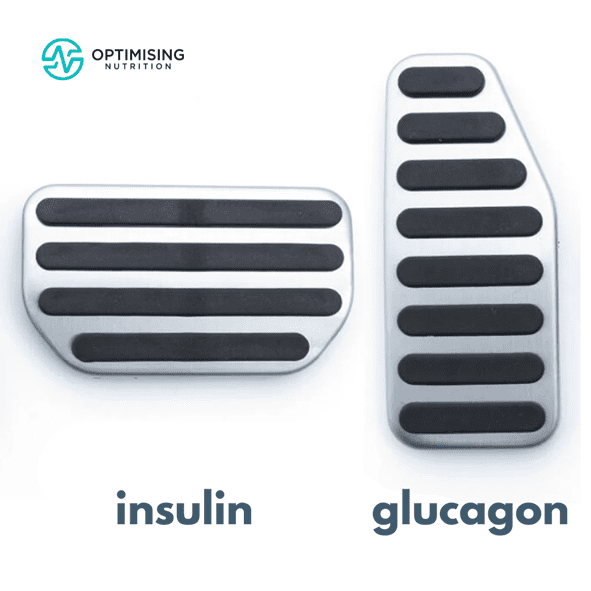

Between meals, your pancreas produces less insulin and more of the balancing hormone glucagon. Increased glucagon allows the body to release stored energy from the liver and body fat into your bloodstream to fuel your organs, brain, and muscles.

When you eat again later, the food is absorbed, and the fat and glucose levels rise in your bloodstream. As a result, your pancreas produces more insulin and less glucagon to regulate the energy in your bloodstream and focus on using the energy that just came in via your mouth.

Given what you know now about the role of insulin and glucagon in the body, you could liken them to the brake and gas pedals in your car. When someone begins eating, insulin puts the brakes on energy release so your body can use up the fuel coming in from your mouth. Likewise, when glucagon is higher between meals, it accelerates the release of stored energy.

Because your body has a limited capacity to store glucose, your body responds more rapidly to dietary carbohydrates.

In contrast, insulin rises more gradually in response to fats because it is stored more efficiently by your body and used more slowly.

To learn more, check out:

What Would Happen If You Didn’t Have Enough Insulin?

To understand what happens when you have excess insulin, it can be helpful to see what happens at the other end of the spectrum if you don’t have enough insulin.

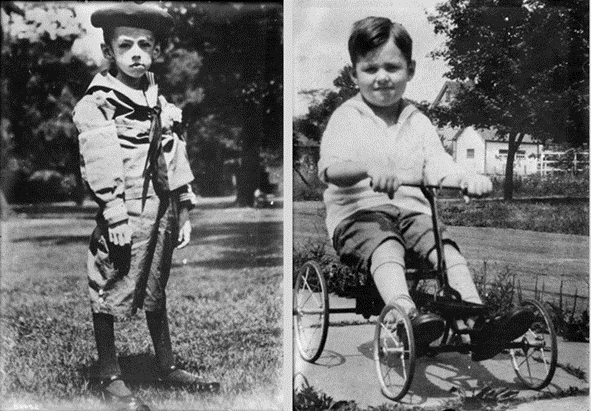

Type 1 diabetes occurs when the body develops an autoimmune response that targets the beta cells of the pancreas to the point where they cannot produce enough insulin. As a result, their stored energy floods into their bloodstream without bounds, and they see elevated blood glucose, ketones, and free fatty acids.

Before long, all their stored energy flows into their bloodstream. This flood of stored energy is not limited to body fat but also all the protein in their muscles and organs and any stored glucose they might have. Eventually, they will die without injected insulin.

The photo below shows an extreme example of what happens when people with Type 1 diabetes can’t produce enough insulin — they lose weight quickly and waste away (as shown in the photo on the left). However, they can quickly regain weight once they get enough insulin. The photo on the right is the same child after taking insulin.

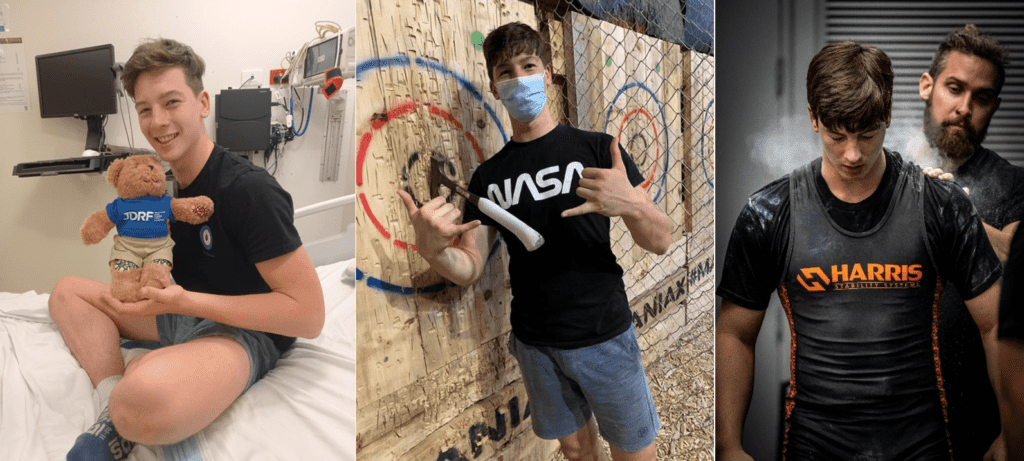

In another example, a bit closer to home, my fifteen-year-old son was recently diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. The photo on the left shows him in the hospital with a blood sugar of 23 mmol/L (or 420 mg/dL) and an HbA1c of 14.5%! The photo on the right shows him five weeks later doing some father-son axe throwing. The final photo is at his first powerlifting competition, four months after diagnosis.

He’s now 13 kg heavier than at diagnosis but much stronger, has a healthy HbA1c of 5.5 %, and is pursuing ambitious athletic goals. While insulin is often seen as a fat-storage hormone, adequate insulin and insulin sensitivity are critical for building and maintaining muscle.

Does Insulin Make Me Fat?

While insulin is critical to keep our energy reserves tucked away after we eat, the insulin you make in response to the food you eat does not make you fat.

Your body is highly efficient and does not produce more insulin than it requires to manage the fuel coming in via your mouth and the energy stored in your body.

Many people incorrectly believe that it’s the insulin that’s making them fat. However, it’s the reverse: the more body fat you have, the more insulin you must produce to keep all your extra energy stored away.

Indeed, some people who start injecting insulin when they’re diagnosed with diabetes do gain weight. This is because the insulin they take to treat their Type 2 diabetes stores the extra fuel they have floating around in their bloodstream, making them hungry, so they eat more.

Exogenous (injected) insulin can lower their blood glucose below what their body is comfortable with, stimulating appetite and often provoking less-than-optimal food choices. In both instances, they gain more fat, which requires more insulin to keep that fat in storage.

While an excessive amount of injected insulin can make you eat more, it can’t store food you don’t eat.

For more details, see

- What Does Insulin Do in Your Body? and

- The Real Reason You’re Insulin Resistant and The Macros to Reverse It

Reactive Hypoglycaemia

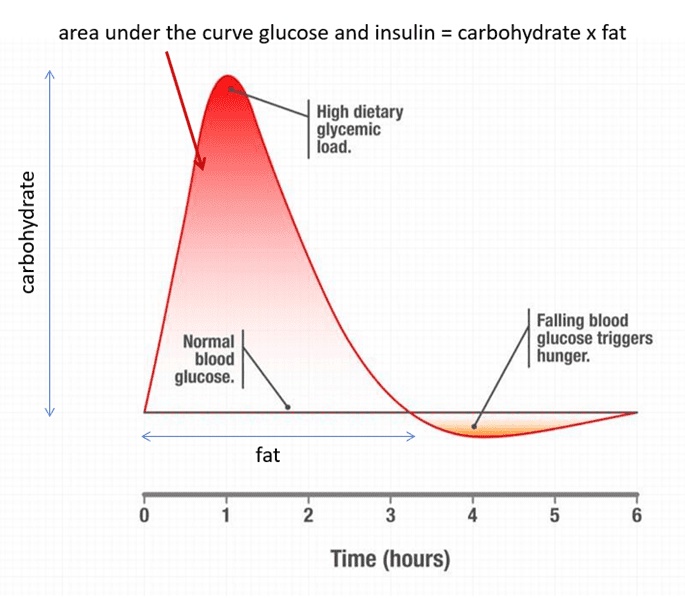

People who are insulin-resistant are also more likely to experience reactive hypoglycaemia.

With reactive hypoglycaemia, low blood sugar occurs shortly after a meal, usually within four hours after eating. This is different to low blood glucose levels, which can occur when we delay longer than usual.

When we eat carbohydrates, our blood glucose rises quickly, and our pancreas releases insulin to slow the release of stored fuel until the energy in the blood is used up.

Unfortunately, people who are insulin resistant often produce more insulin than they require to bring their blood sugars back to baseline. This causes a rapid drop in blood glucose below what is normal for them, which can cause them to feel a range of negative symptoms, like anxiety, irritability, racing heart rate, brain fog, and shakiness.

Your body doesn’t like high glucose levels. However, significant increases in glucose also lead to rapid drops below what their bodies are comfortable with. When our glucose drops below what is normal for us, we feel ravenous.

When blood sugar drops below what we feel comfortable with, our brain perceives starvation and sends us in search of energy-dense foods to bring up glucose quickly. Unfortunately, this intense hunger can lead to poorer food choices, overeating, more fat storage, and higher insulin levels.

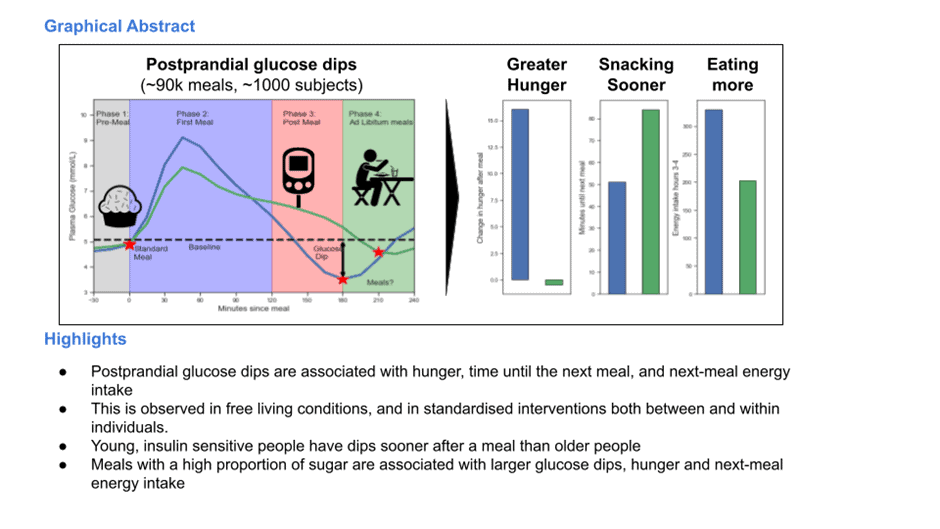

The recent PREDICT study run by ZOE comprised nearly one thousand people who wore continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and shared their readings. One of the study’s conclusions was that people who experienced more significant dips in their blood glucose after eating were more likely to feel hungrier, eat more, and gain weight.

To manage this, in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, we guide people to avoid reactive hypoglycaemia by:

- Reducing their processed carbohydrate intake if their blood glucose rises by more than 30 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) after meals,

- Eating when they are hungry and below their normal pre-meal glucose trigger and

- Targeting carbohydrates to quickly bring their glucose back into the normal range if their glucose drops significantly below normal.

Fortunately, most people in our challenges don’t need to worry too much about excessive hunger due to reactive hypoglycaemia. The chart below shows that the average glucose rise after eating across the 4,402 people using the Data-Driven Fasting app is only 16 mg/dL (or 0.9 mmol/L).

On the far right, you can see a handful of people who are insulin-resistant and need to pay attention to their intake of refined carbohydrates to avoid reactive hypoglycaemia before simply focusing on their blood sugar before eating.

Interestingly, on the left of the chart, we can see that many people experience a glucose drop after eating. This often occurs when people prioritise nutrient-dense foods and meals with a higher protein % — a technique many use to manage their blood sugars by eating nutritious meals sooner.

For more on the effect of higher protein meals on blood sugars, see:

- Reactive Hypoglycaemia: Symptoms, Causes & Dietary Solutions

- Making Sense of the Food Insulin Index

- Why Does My Blood Sugar Drop (or Rise) After Eating Protein?

Do Carbohydrates Cause Insulin Resistance?

Some people believe carbohydrates are the primary cause of insulin resistance because they raise insulin the most and the fastest.

Sadly, this logic does not consider that most of the insulin our pancreas produces daily works to hold our stored energy in storage. Having two people with Type 1 Diabetes in my household (my wife and my son) provides some fascinating insights.

Around 70–80% of the insulin we produce across the day is basal insulin, or the ‘background’ insulin required to maintain blood sugar levels and keep stored energy from flowing into the bloodstream without food. Hence, only 20–30% of their insulin demand is bolus insulin, or insulin required to manage their blood sugar around meals.

While reducing carbohydrates to stabilise blood sugars into a normal, healthy range is wise, it’s not necessary to swap all carbohydrates for fat to achieve extremely stable blood glucose levels in the belief that they can effectively turn off their pancreas.

For more details, see:

- How To Use a Continuous Glucose monitor for weight loss (and why your CGM Could Be Making You Fat)

- Glucose Revolution by Jessie Inchauspe (the Glucose Goddess): Review

- Keto Lie #10: Stable Blood Sugars Will Lead to Fat Loss

What Is the Best Way to Fix Insulin Resistance?

Reducing carbohydrates will help reduce your blood glucose and even your HbA1c. But this may only be symptom management. Unless you reduce your body fat levels, you won’t address the root cause of insulin resistance: energy toxicity.

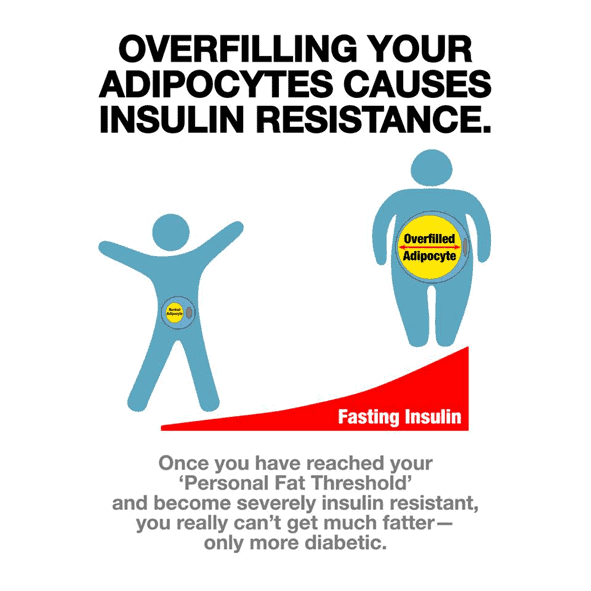

Insulin’s main role is to keep your energy reserves tucked away in storage. However, once you exceed what we know as your Personal Fat Threshold, your body struggles to produce enough insulin to do its job. As a result, excess energy overflows into your bloodstream and registers on your meter as high blood glucose, ketones, and fatty acids.

So, to fix your insulin resistance, you need to address the root cause.

Does Dietary Fat Cause Insulin Resistance?

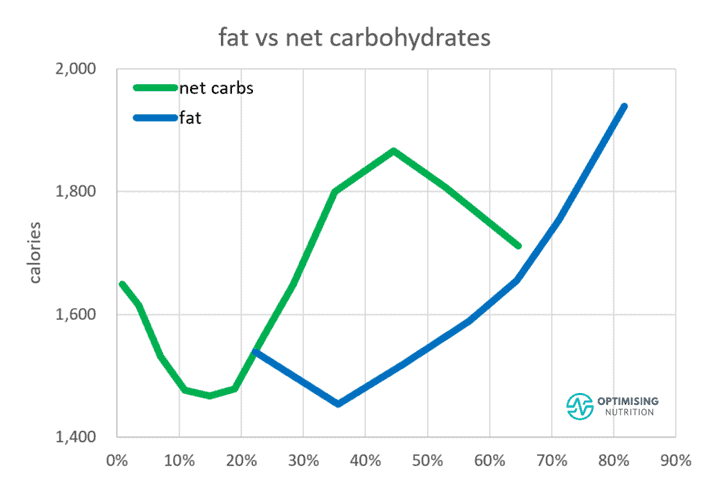

While many point the finger at carbs, believing that people with insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes are intolerant to carbohydrates, others believe that dietary fat is the primary culprit that has made us all obese and insulin resistant. This is partially true, but it’s not the whole story.

People who reduce carbs on a low-carb diet tend to increase their protein. This leads to greater satiety and often ‘effortless weight loss’. But unfortunately, the benefit of a lower-carb diet is misattributed to fat rather than protein.

It’s hard to avoid all fat if you’re getting adequate protein. The fat that comes with your protein is a great fuel source, but there’s no need to go out of your way to overconsume it or chase elevated ketones.

Fat doesn’t raise glucose and insulin much in the short term. But this is because we have more room to store fat relative to carbohydrates, so fat is welcomed aboard. Due to oxidative priority, fat is last in line to be used for fuel. So, if you’re eating more energy than you use, it’s likely to be stored as body fat. As more fat is stored, you will need more basal insulin to store all that energy.

Additionally, fat is the most calorically dense macronutrient. Because calories in always equal calories out, ‘keeping calm and ketoing on’, ‘eating fat to satiety,’ and ‘eating more fat to burn fat’ will likely contribute to your energy toxicity.

For more on finding your ideal fat intake, see Fat – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR).

What Is the Main Cause of Insulin Resistance?

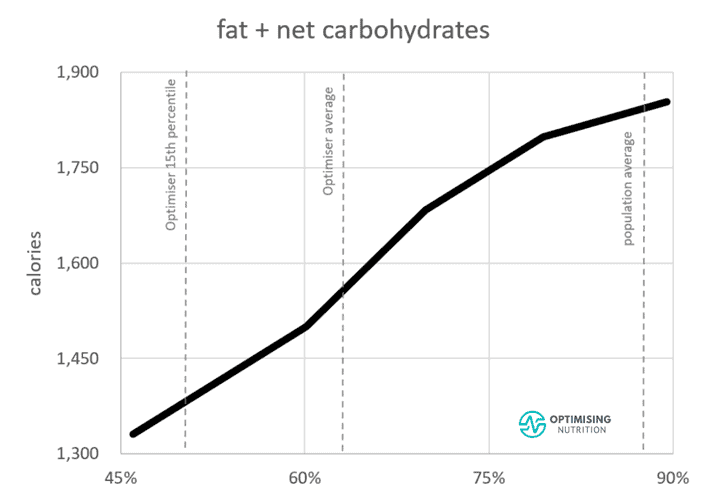

The bottom line is that to reverse insulin resistance, you need to reduce your body fat.

To reduce your body fat, you must eat in a way that increases satiety and allows you to sustain an energy deficit so you can decrease your body fat levels below your Personal Fat Threshold.

In the end, any food that causes you to store more energy will increase body fat levels and energy toxicity and worsen your insulin resistance. As the chart below from our satiety analysis shows, reducing carbohydrates or fat has similar effects on satiety.

While most people tend to swing to the low-fat or low-carb camp, reducing your intake of refined carbohydrates, fat, or both will increase the percentage of total calories you’re consuming from protein. As a result, this will improve your satiety and help you eat less. Combining refined carbs and fat and neglecting protein and fibre aligns with eating more.

Our in-depth satiety analysis indicates that the foods that provide the greatest satiety contain more nutrients and less energy. Hence, nutrient density is positively correlated to satiety. Subsequently, focusing more on high-satiety, nutrient-dense foods is critical so you can feel fuller on fewer calories and lose weight.

For more details, see:

- High-Satiety Index Foods: Which Ones Will Keep You Full With Fewer Calories?

- Highest Satiety Index Meals and Recipes

- Fat – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR)

- Carbohydrates – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR)

- Protein – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR)

What Causes Insulin Resistance?

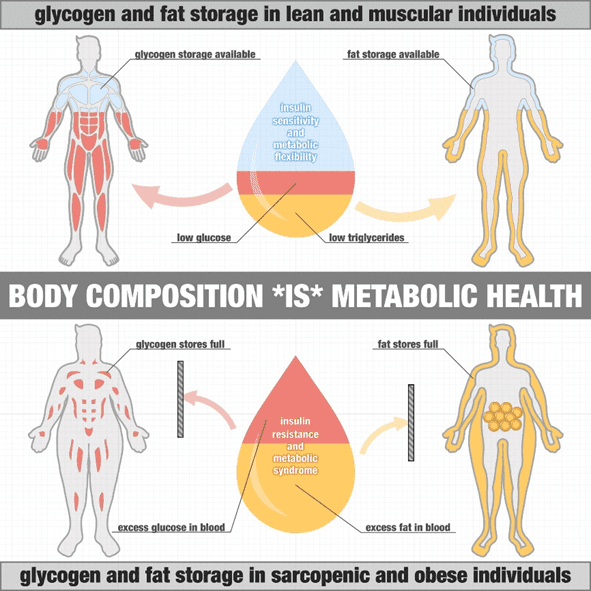

Insulin resistance occurs when the body tries to store more energy than it comfortably can.

While your appetite ensures you have enough body fat and glucose to fuel your everyday needs, there is a limit to how much your body can hold.

When you have minimal body fat, your pancreas only needs to produce a little insulin to hold your energy reserves in storage. However, as you get fatter, your pancreas must work harder and harder to produce more insulin to stop the stored fat, glucose, and stored protein (muscles and organs) from flowing into your bloodstream.

Eventually, the pressure becomes excessive, and insulin can no longer do its job effectively. At this point, you’ve exceeded your Personal Fat Threshold, you’re now insulin resistant, and the stored energy must overflow into your bloodstream.

For more on this, see:

- Personal Fat Threshold Model of Insulin Resistance, Diabetes and Obesity vs the Carbohydrate Insulin Model

- The Real Reason You’re Insulin Resistant and the Macros to Reverse It

Your Veins Are Like a Hose…

The fuel in your blood is in a constant state of flux. Energy constantly flows from storage through your liver and to your brain, muscles, and organs. Hence, you can liken your veins to a hose connected to a tank.

- Insulin is the signal that regulates the flow of fuel from the tank via the tap.

- Your liver is the tap that allows fuel to flow into your bloodstream.

- The fuller the tank, the harder your pancreas needs to work to turn off the tap and hold back the pressure. The more body fat you have, the greater the energy pressure that needs to be held back.

- On the other end, if you have large and active muscles, they will drain the energy from your bloodstream quickly. However, the energy in your veins will continue to back up if your muscles are smaller and less active.

Can You Fix Your Insulin Resistance?

Now that we’ve set the scene, you can see that the solution is twofold. The key to reversing insulin resistance requires the management of energy usage and energy input.

Use More Energy

On the energy-out end, you must increase your activity output and build stronger muscles that require more fuel. This can involve general activity, like increasing your non-activity exercise thermogenesis (NEAT) and incorporating resistance training into your regimen to grow your muscle.

See Optimising Your Exercise [Macros Masterclass FAQ #7] for more thoughts on exercise.

Drain the Tank

On the other side of the equation, you have to drain some of your energy reserves by consuming less energy — specifically from fat and carbs — while still consuming the protein your body requires to maintain your lean mass supply and the vitamins and minerals required to allow your cells to use the energy from the food you eat and on your body.

Sadly, most people fail over the long term when they try to eat less of the same foods — their hunger always wins out in the end. So, to manage how much you eat, you need to change what you eat!

What Is the Fastest Way to Reverse Insulin Resistance?

Because the root cause of insulin resistance is energy toxicity, one key to reversing it is to drain your energy stores.

While this might have you enthused to hop on the prolonged fasting train or hop right into a low-carb, low-fat, high-protein, and high-fibre protein-sparing modified fast (PSMF)-type diet, this might do you more harm than good.

However, when you jump to extremes, your body tends to notice and respond aggressively.

Because it takes more time and energy to turn the amino acids in protein into usable fuel (ATP), if you immediately try swapping out all your usual fat and carbs for meals of only protein, you are likely to experience cravings not long after eating. As a result, you might feel compelled to binge on ‘easy energy’ sources.

Additionally, throwing yourself into a long-term fast might work… initially. But as your body undergoes self-inflicted starvation for longer and longer, your body will begin to perceive it as such and respond accordingly.

When you go to refuel, you might have uncontrollable urges to binge on fat-and-carb combo junk to refill the energy stores you just fasted away. At the same time, your body might take to feasting on your metabolically active lean muscle mass to make up for the protein it’s not getting. Over time, this can decrease your metabolic rate and cause you to gain more weight over the long term.

Hence, the fastest way to reverse insulin resistance might not be the best solution in the long run! For more, see:

- Secrets of the Nutrient-Dense Protein Sparing Modified Fast (PSMF) Diet

- How Much Weight Should I Lose Per Week?

How Can You Fix Your Insulin Resistance?

To fundamentally reverse your insulin resistance, you need to find a way to reduce your body fat while preserving precious lean muscle mass over the long term.

In our Macros Masterclass, we guide people through slowly dialling back their energy intake from carbs, fat, or both while scaling up their protein and fibre consumption to promote satiety and preserve their lean mass.

In our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, we walk people through using their glucose meter as a fuel gauge to ensure they are progressively depleting the glucose in their bloodstream. When glucose drops, your body turns to stored body fat for fuel and begins to use up some of the extra energy it has stored on board.

If you already have a glucose meter, we’d love for you to try out our Data-Driven Fasting app and use it to guide what and when you eat so you can begin reversing your insulin resistance.

More

- Reactive Hypoglycaemia: Symptoms, Causes & Dietary Solutions

- The Most Nutrient-Dense Foods – Tailored to Your Goals and Preferences

- Nutrient-Dense Meals and Recipes

- Data-Driven Fasting: How to Lose Weight and Reverse Type-2 Diabetes Without Tracking Your Food

- Macros Masterclass

- Personal Fat Threshold Model of Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Obesity