Embark on an exploration of glucagon vs. insulin—the two crucial hormones that act as the accelerator and brake pedal of your metabolism.

This article elucidates the distinct roles they play in managing your energy resources and how their balance is paramount to your health and well-being. Through a deep dive into the science and the practical implications, you will grasp the dynamics of glucagon vs. Insulin.

Understanding these hormones’ interaction and their impact on your body not only sheds light on the fundamental workings of your metabolic system but also opens avenues to better manage and potentially improve your overall health.

This isn’t merely a scientific endeavour; it’s a leap towards optimizing your metabolic health in a sustainable manner, providing you with the knowledge to make informed decisions about your nutrition and lifestyle.

- The Brake (Insulin) and the Accelerator (Glucagon)

- Glucagon and Type-1 Diabetes

- Glucagon and Type-2 Diabetes

- Glucagon is Central to Diabetes

- Energy Toxicity

- How to Optimise Your Glucagon and Insulin?

- Carbs for Fuel

- How to Ensure You Don’t Overfill Your Glucose Fuel Tank

- Fat for Fuel

- How to Recalibrate Your Hunger Signals

- Progressive Overload for Your Metabolism

- Should You Fear Gluconeogenesis?

- Too Much Gluconeogenesis Can Be Bad

- Do You Really Want to ‘Maximise Your Energy Efficiency’?

- Why You Don’t Want to Achieve Flatline Blood Glucose

- How to Balance Your Glucose Across the Day

- Look After the Fuels, and the Hormones Will Look After Themselves

The Brake (Insulin) and the Accelerator (Glucagon)

Because we can easily measure glucose in our blood, it’s easy to think that the food you eat goes directly into your bloodstream. It is a bit like:

Eat an apple -> apple goes into bloodstream -> glucose rises on CGM.

But this would be like going to the gas station and thinking you’re pouring the fuel directly into your car’s fuel lines for immediate use.

But it just doesn’t happen like that! That would be stupid and dangerous! Your car would explode into a fireball before you made it out of the driveway.

Instead, you pour the gas into the fuel tank. Then, your carburettor gradually regulates the fuel intake into the motor as required.

Similarly, the energy from the food we eat is digested and goes into storage for later use.

Your body has several fuel tanks that store the fat and glucose we get from food. Your muscles and liver can hold about 500 grams or so of glucose in its storage form, glycogen. This is the most easily accessible storage form of stored energy that your body uses to fuel intense activity.

Meanwhile, the adipose tissue on our bum, belly, hips, and thighs can hold much more energy. However, it’s not infinite and a bit harder to access if your glycogen fuel tanks are full to the brim.

Based on whether or not there is energy available in your bloodstream, the beta cells of your pancreas secrete insulin, or the alpha cells will release glucagon based on the current energy in your bloodstream.

These counterregulatory hormones work in tandem to signal to your liver to release more or less of the previously stored energy into your bloodstream as required.

- After you eat, there is lots of energy in the blood. So, insulin rises to hold back energy in storage, and glucagon drops.

- When you have gone without food for some time, there is less energy in the blood. So, insulin drops, and glucagon rises to push stored energy into the bloodstream.

Insulin is like the brake for your metabolism, while glucagon is the accelerator for your metabolism.

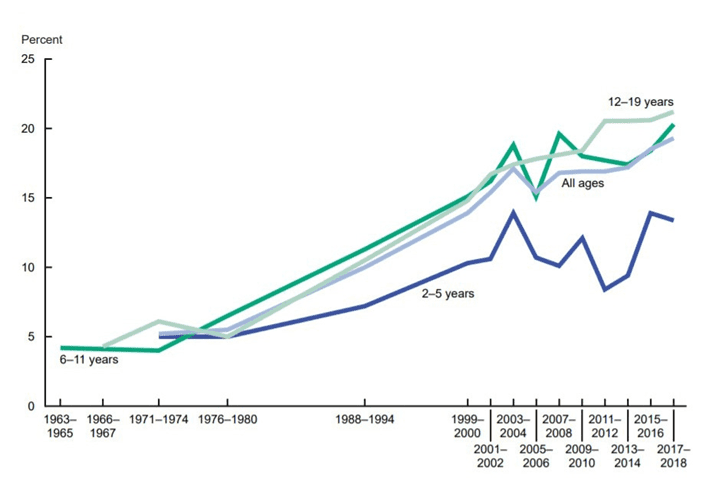

With so many of us now in the obese category, it might sound like more glucagon might be great to utilise all our stored energy quickly.

What if we could turn off insulin to allow glucagon to accelerate fat loss even faster?

The ‘good news’: It can be done.

About 0.01% of people have ‘mastered’ this.

However, the bad news is that it isn’t that cool.

It’s actually a diagnosed medical condition called Type-1 Diabetes.

Glucagon and Type-1 Diabetes

Glucagon doesn’t usually get much attention because it’s not a commonly used drug. However, understanding how people manage Type 1 Diabetes gives us some insight into how glucagon works.

People with Type-1 Diabetes usually lose the function of their beta cells because of an autoimmune response, meaning their insulin production is typically affected. Hence, their alpha cells still produce glucagon. This means your body is constantly ‘pushing’ fuel into your bloodstream with no counterregulatory insulin ‘brake’.

Without insulin, people with uncontrolled Type-1 Diabetes constantly and quickly release all their stored glucose, fat, and protein (from their muscles and organs) into their bloodstream.

While this would have been a death sentence a century ago, exogenous (injected) insulin quickly corrects this problem, as illustrated in the before and after photos below.

Thankfully, people with Type-1 Diabetes these days can lead normal healthy lives with the intelligent use of exogenous insulin and some dietary tweaks. In fact, people with Type 1 Diabetes are sometimes healthier than the general population because they must be more intentional about their eating.

We have a few boxes of insulin and a couple of glucagon syringes in the fridge at home. Fortunately, my wife, who has had Type 1 Diabetes for thirty-five years, has never had to use one. Neither has my son, who was diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes in December 2021.

However, in the case of an emergency, if they inject too much insulin, glucagon can be injected to force more glycogen from the liver to revive them.

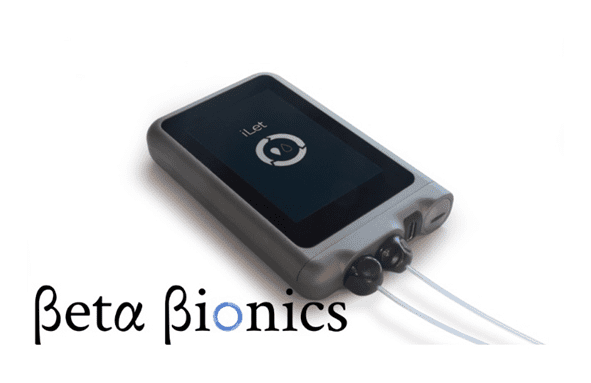

The iLet closed-loop insulin/glucagon pump system runs both insulin and glucagon to boost glucose levels if they go low automatically. However, because Type 1s still naturally produce glucagon in the alpha cells, there doesn’t appear to be a massive benefit despite the extra complexity.

For more on Type-1 Diabetes, see How to Optimise Type-1 Diabetes Management (Without Losing Your Mind).

Glucagon and Type-2 Diabetes

In Type-2 Diabetes, the balance between glucagon and insulin is critical. People with Type 2 diabetes still produce insulin and glucagon; their pancreas often works overtime to pump out extra glucagon and insulin in the early years.

Because extra weight above someone’s Personal Fat Threshold often underlies Type-2 Diabetes, someone with T2D typically has a LOT of extra stored energy. So, while we often think of Type 2 Diabetes as a problem with carbohydrate metabolism, the root cause is really overfilling our fat fuel tanks beyond what our bodies are comfortable with.

Subsequently, their alpha cells work night and day, pushing out glucagon to signal to the liver to unload some of that burden by pushing out the energy stored in their liver and fat cells.

But in Type 2 Diabetes, the beta cells are also working overtime, trying to put the ‘brakes’ on to slow the release of stored energy from flowing into their bloodstream.

Eventually, these people can experience pancreatic burnout and rapid weight loss when their beta cells give up.

But, in contrast to T1D, these people have become ‘insulin resistant’. Because their fat cells are full, their bodies have become resistant to the effects of insulin. So, while they produce enough insulin, their cells are no longer sensitive to its signalling effects that allow glucose into the cell (i.e., its anabolic role), and insulin is no longer effective at holding stored energy back.

Glucagon alone would be a very effective weight loss drug, other than the diabetic ketoacidosis, muscle loss and extremely high levels of glucose, ketones and free fatty acids in the blood that accompany it (i.e., don’t try this at home)!

For more details on Type 2 Diabetes and insulin resistance, see:

- Personal Fat Threshold Model of Insulin Resistance, Diabetes and Obesity, and

- What Is Insulin Resistance (and How to Reverse It)?

Glucagon is Central to Diabetes

On the podcast where he is defending Ray Peat’s bioenergetic views, Jay Feldman referenced studies in mice where glucagon production was turned off, which ‘fixed’ their diabetes.

This is technically correct, but if you did this to a human who kept eating the same hyper-palatable, low-satiety, nutrient-poor junk food, they would continue eating and storing more energy and not releasing any into the bloodstream.

You might have lowered your blood glucose, but you would blow up like a balloon ready to explode because you can’t release stored energy into your bloodstream!?!?

If you want an excellent deep dive into the glucagon-centric view of diabetes, check out this lecture from Roger Unger.

In summary, the key takeaways are:

- To reduce glucagon: have less stored energy that your body wants to push into the bloodstream.

- To reduce insulin: have less stored energy for your body to hold back in storage.

Energy Toxicity

In the low-carb and keto worlds, many have been fear-mongered into believing ‘insulin toxicity’ is the root cause of everything bad.

But just because many diseases and high insulin levels tend to coincide does not mean insulin itself is the root cause.

On the other side of the spectrum, people on the high-carb side fear-monger others into believing that glucagon is the root cause of everything bad.

But your body is not dumb. It’s actually highly efficient and intelligent!

Your pancreas doesn’t waste precious energy to make more insulin or glucagon than required to respond to the foods you eat and keep the energy within your blood in a tight range.

How to Optimise Your Glucagon and Insulin?

Fortunately, most of us don’t have to micromanage our insulin and glucagon like someone with Type 1 Diabetes does! Your pancreas will do it for you if you just give it the right inputs.

The solution lies upstream. To reduce insulin and glucagon, you must manage your body fat levels! If you’re overfat and exceeding your Personal Fat Threshold, you need to find a way to achieve and maintain an energy deficit.

This is not a simple matter of eating less and moving more. Sheer willpower and deprivation rarely work for long.

To do this, you must find a way to eat that controls your appetite and minimises cravings that will drive you to overeat when trashy hyper-palatable comfort foods are available!

If we draw the battle lines of insulin vs glucagon, the warring extreme camps could use this as ammo to go after their chosen enemy energy source (i.e., carbs or fat) and swing to the other extreme.

But instead of choosing an extreme side, what if we could choose a metric to manage that dictates our insulin and glucagon?

We can use our blood sugars as insight to determine whether we’ve filled the right fuel tank and which fuel we need right now.

Let me explain.

Carbs for Fuel

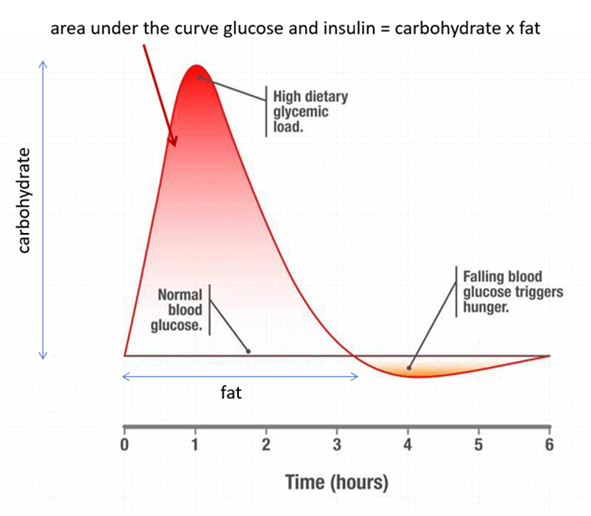

As the chart below shows, carbs raise our blood sugar in the short term. If our glucose levels rise by more than our body is comfortable with, our body releases insulin to slow the release of fuel from our liver until we use that glucose.

We start to see problems in someone who is insulin resistant. These people release a little too much insulin, and their glucose levels come crashing down to below what is normal for them. At this point, cortisol and glucagon release energy into the bloodstream to bring glucose back into range.

If your glucose levels swing too far below what your body is comfortable with, you’ll trigger a stress response as your body perceives starvation. This crash in glucose after high glucose levels is often known as reactive hypoglycaemia. This also wakes up your lizard brain, which takes over and ensures you get food NOW!

Unfortunately, Lizzy doesn’t have a sophisticated palate and points you in the direction of foods that fill all your fuel tanks and raise your blood glucose levels back to normal the fastest.

When Lizzy rages, we tend to eat more than we need to, and our glucose levels shoot up again. This ‘blood sugar rollercoaster’ cycle of highs and lows continues, particularly for those who are obese and (or) insulin-resistant.

Zoe’s ‘Big Dipper’ study (Postprandial glycaemic dips predict appetite and energy intake in healthy individuals) elegantly showed that people with larger swings in glucose tend to eat more than they need to when their glucose drops lower than they’re comfortable with.

How to Ensure You Don’t Overfill Your Glucose Fuel Tank

The simple solution here is not to overfill your glucose fuel tank. While this might sound challenging, you can use some easy and inexpensive tools to ensure you follow through.

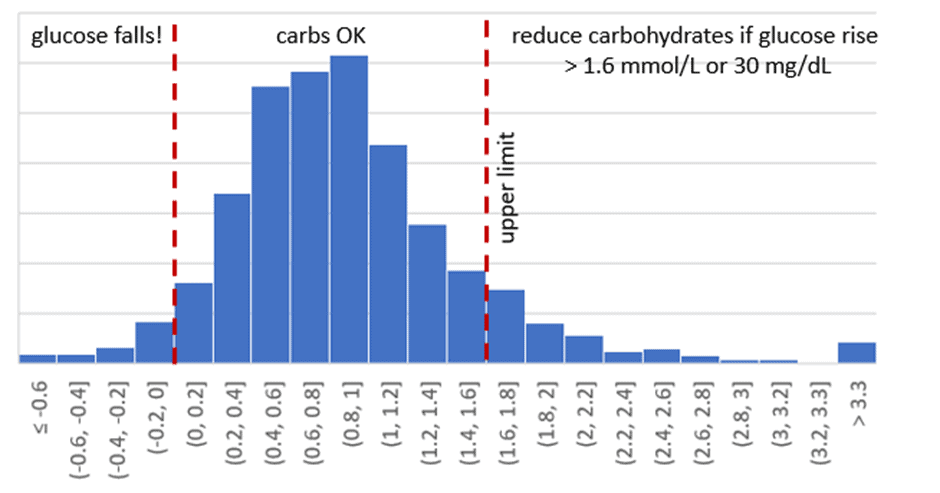

In our Macros Masterclass and Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, we guide people to reflect on their blood glucose levels and dial back their intake of carbohydrates if their glucose rises by more than 30 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) after eating.

If your glucose is within that range, you don’t need to worry about your carb intake. However, we recommend ensuring the carbs are from nutrient-dense sources that provide adequate vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids, and amino acids.

However, because you need to get your energy from somewhere, fewer carbs are not necessarily better! But if your rise in glucose after meals is on the upper end of normal, you’re consuming more refined carbs than your body needs and triggering an excessive insulin response.

To put it simply, you’re overfilling your glucose fuel tank with more carbs than your body needs.

The chart below shows the distribution of post-meal glucose rises in our challenges. While there are some high values — about 9% of our DDF challengers find they need to dial back their carbs — they’re pretty healthy for the most part. On average, glucose rises around 16 mg/dL (0.9 mmol/L).

For more details, see What are Normal, Healthy, Non-Diabetic Blood Sugar Levels?

Fat for Fuel

Because many of our Optimisers come from a low-carb or keto background and already have their carbs dialled down pretty low, we end up counselling many people to dial back their fat intake in our classes.

While fat doesn’t raise glucose levels rapidly in the same way carbs do, dietary fat keeps your sugars slightly higher for longer and stops your glucose from dropping below trigger.

Your body loves to use fat as a slow-burning fuel. But as we discussed above, excess dietary fat increases your body fat, raising your insulin levels as your pancreas has more energy to keep in storage.

Your glucose gives some clear insights into the amount of total energy floating around your bloodstream at any given minute. Because your body’s fuel tanks are interconnected, your glucose levels—and ketones and blood fats—will also drop earlier as your body fat levels decrease.

For more on your interconnected fuel tanks that power your hybrid metabolism, see Oxidative Priority: The Key to Unlocking Your Body Fat Stores.

How to Recalibrate Your Hunger Signals

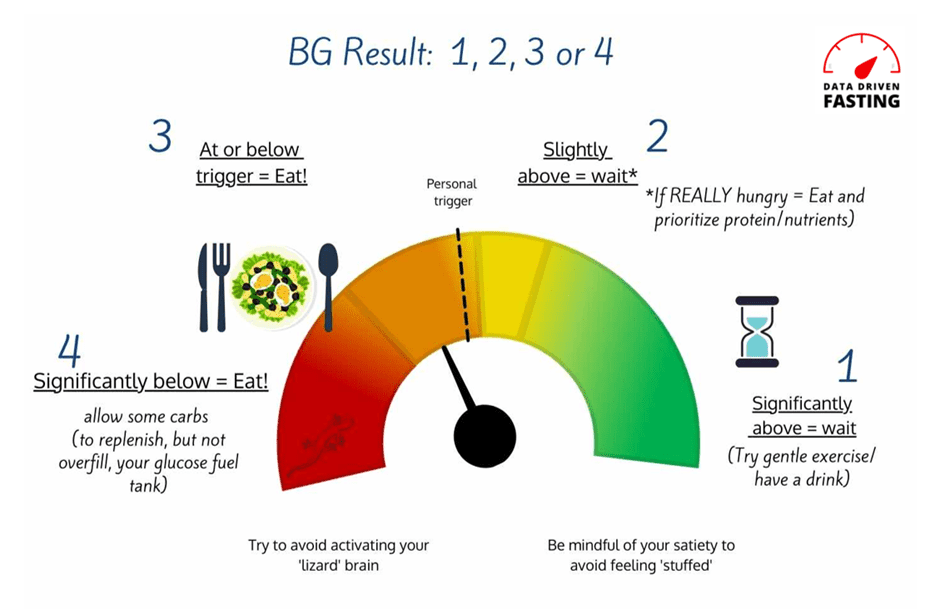

Most people think that eating less fat and carbs will mean less food and more fasting. However, most Optimisers tend to eat more regularly as they use their premeal glucose to guide what and when they eat. This allows them to break free of misguided beliefs like ‘eating fat to satiety does not raise insulin’ and ‘fasting for longer is better’.

In our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, we walk our Optimisers through hunger training, where they recalibrate their hunger using their blood glucose as a guide.

The secret to hunger training is to pay attention to your hunger symptoms and refuel when your glucose indicates you need to. If you wait too long, your blood glucose will fall too low, triggering a stressful cortisol and glucagon response as your body floors the gas pedal to keep your glucose from crashing.

Insulin and glucagon are constantly working to keep the energy in your bloodstream in the normal range. Using your blood glucose as a guide enables you to ensure that you don’t push either to an unhealthy extreme.

While many people keep an eye on their post-meal or waking glucose values, our analysis of half a million blood sugar data points from four thousand people has confirmed that your premeal glucose is the most useful number to manage.

For more details, see:

- What are Normal, Healthy, Non-Diabetic Blood Sugar Levels?

- Insulin is NOT Making You Fat (and Here’s Why)

Progressive Overload for Your Metabolism

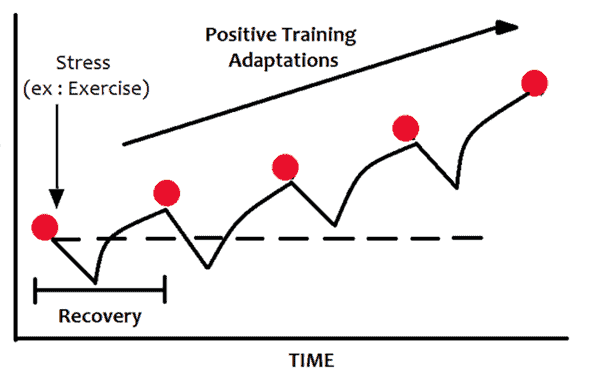

Just as with any intelligent fitness routine, progressive overload is key. In other words, you only want your glucose to drop just below what is normal for you to deplete the excess glucose and fat in your fuel tanks a little, so your body doesn’t have to pump the glucagon pedal too hard.

Over time, this will slowly lower your premeal blood glucose values and bring you to your blood sugar and weight loss goals.

Everyone wants to lose weight and reverse their diabetes overnight. But sadly, overnight changes rarely last! Going too fast too soon makes something seem extreme that may cause you to toss in the towel.

Instead, in our programs, we encourage people to make just enough change to see a sustainable rate of weight loss (e.g., 0.5 to 1.0% per week).

For more details, see How Much Weight Should I Lose Per Week?

Should You Fear Gluconeogenesis?

For a few years, many people in the keto world avoided protein out of fear of gluconeogenesis. They believed protein would convert instantly into glucose in their blood. However, adequate insulin suppresses excessive gluconeogenesis to ensure blood sugars remain stable.

Avoiding protein to try and stabilise blood sugars is perhaps the dumbest thing anyone could do. Protein is the most satiating macronutrient, meaning you will eat less when you prioritise protein over energy from carbs and fat. In time, fat loss will lead to improved insulin sensitivity.

Additionally, the amino acids in protein are necessary to build lean muscle mass. Adequate protein enables someone to preserve lean muscle mass and stay full on fewer calories to lose fat while preserving their precious muscle.

Thus, adequate protein is critical for addressing the root cause of insulin resistance: energy toxicity.

Too Much Gluconeogenesis Can Be Bad

In his podcast, Jay Feldman argues that gluconeogenesis raises glucagon and is inefficient and stressful for the body. To some extent, I agree with this—but context is critical.

For example, a very high protein % diet (e.g., a very low-calorie, 60% PSMF) will force the body to liberate stored energy rapidly and use your dietary protein to create glucose (via gluconeogenesis). Like heavy resistance training, this can be challenging for your body, and more is not necessarily better.

Although your body can create glucose from protein via gluconeogenesis, it’s not your body’s preferred fuel source. We lose around 10-35% of the energy we consume from protein when we turn it into usable fuel (ATP) and in muscle protein synthesis. Hence, it can actually increase appetite if we’re not giving our bodies the right balance of nutrients and fuel.

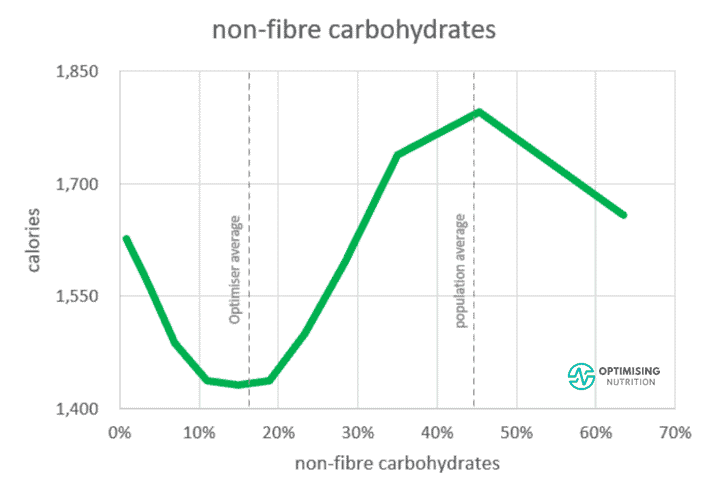

When we look at the satiety response to non-fibre carbs below, we see the sweet spot for satiety is 10-20% of calories from non-fibre carbs. This is likely because when we cut out all carbs, our bodies crave some glucose, and we end up eating more.

Although the brain can survive without it and make glucose from protein, it is not optimal, especially for long periods. Because it’s hard work to make enough glucose from protein, your body will keep seeking out more food to get some glucose.

So, if your goal is to maximise satiety, you probably don’t want to drop your net carbs below 10% of calories. But at the same time, there’s no need to drown yourself in honey and fruit to avoid gluconeogenesis at all costs — you’ll just overfill your glucose fuel tank and downregulate fat oxidation.

As we can see from the vertical line to the right of the carb-satiety chart above, the population’s average carb intake is about 45%, with much of the rest from industrial seed oils.

As a result, their diets comprise the low-protein, poorly satiating, carb+fat combo that gets us hooked on eating MORE. Hence, lowering carbs while prioritising protein increases satiety, enabling us to eat less, reverse energy toxicity, and decrease our insulin demand.

Interestingly, towards the right of the chart above, we see a dip in energy intake when people push their non-fibre carbs above 50% and their fat low. However, our analysis from 150,000 days of Nutrient Optimiser data and half a million days of food entries from MyFitnessPal suggests there aren’t many people who can maintain a greater than 50% carb, low-fat diet.

Do You Really Want to ‘Maximise Your Energy Efficiency’?

Returning to the listener’s question to Robb Wolf that started all this, they asked:

‘I’m curious about your thoughts on Ray Peat’s bioenergetic view of health. The bioenergetic view—at a high level—is about increasing energy at the cellular level and decreasing stress, which would increase your metabolism in turn.

Increasing energy and metabolism gives the body more resources to perform all the necessary functions the body needs to perform (i.e., digestion, healing, fighting illness, etc.)’.

To do this, one of the main things Peat recommends is to eat sugar because it’s the preferred form of fuel for our cells. Peat recommends simple sugars, like sucrose, which is found in fruit, fruit juice, honey, and white sugar. He favours these sugars because they are easily absorbed, digested, and converted into energy.

Peat believes low blood sugar increases stress hormones like glucagon, adrenalin, and cortisol, which increases tissue breakdown, fat release, and fatty acid formation in an attempt to provide fuel for the body.

As a result, the body perceives starvation and survival over time. This leads to low energy, a slowed metabolism, and reduced thyroid function, ultimately putting the body in a chronically stressed state.

While Ray Peat’s sugar recommendations may seem ludicrous to people with a low-carb background, I think he has a few good principles. For example, fast-acting carbs can be a handy tool. But let me explain!

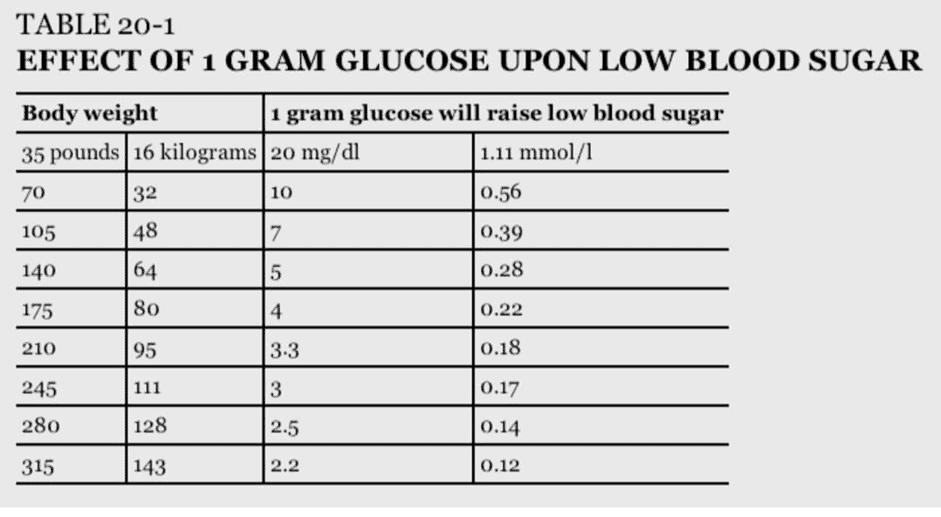

My wife and son both have Type-1 Diabetes. For them, fast-acting glucose will always play a critical role. The smartest people with T1D who have the best glucose control know exactly how much glucose they require to raise their blood sugar back to target without overshooting. This keeps them off the glucose-insulin rollercoaster.

The table below shows how much carbs are required to raise glucose precisely — it’s not much!

Why You Don’t Want to Achieve Flatline Blood Glucose

I think CGMs are often a disservice to the many biohackers without T1D. Many people find themselves paralysed as they try to tame their glucose curve.

They often end up trying to ‘flatline’ their glucose variability by avoiding all carbs and sometimes even protein while prioritising fat, which often leads to energy toxicity.

Whether you’re a T1D, T2D, or just someone who eats low- or no-carb, some carbohydrates can benefit someone when glucose levels are low.

We’ve seen many people from a hardcore keto or carnivore background strategically apply these fast-acting carbs to boost their glucose when they’re below their normal based on the guidance of our Data-Driven Fasting app. They often see experience greater satiety and restart their weight loss results.

But—as always, with extremes—if you focus on fast-acting sugar to the nth degree and minimise protein because ‘it is stressful, inefficient, and increases glucagon’, we end up with a pretty crappy nutrient-poor diet.

In fact, our current food system is set up to maximise efficiency. We add synthetic fertilisers to mono-crops to rapidly create sugar, starch, and industrial seed oils, which we use to make ultra-processed foods.

These ‘foods’ are low in protein, fibre, and essential nutrients, which makes them highly inefficient raw ingredients for energy synthesis in our mitochondria. In contrast, they are great sources of stored energy, which increases insulin again.

How to Balance Your Glucose Across the Day

In the podcast, Jay Feldman mentioned that people on a lower-carb diet tend to see higher fasting glucose because glucagon output and gluconeogenesis increase overnight.

This is correct and a common pattern we see in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges. However, it is not necessarily a bad thing.

Based on the type of macronutrients you prefer to get your energy from (i.e., fat or carbs), your blood sugar may tend to be higher or lower at different points throughout the day.

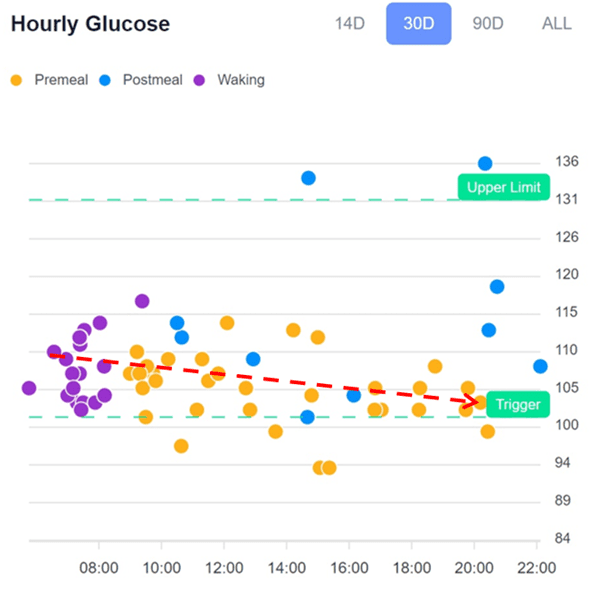

Low Carb Glucose Pattern

The chart below shows a typical low-carb glucose pattern from the hourly chart from the DDF app.

Waking glucose tends to be higher for people on a low-carb diet. This is because, during the day, their bodies use up glucose, which is not directly replenished with diet. Once their glucose drops as they proceed with activity as the day goes on, the DDF app will encourage them to use a few carbs to bring their glucose back into the normal range.

Low Fat Glucose Pattern

Conversely, people on a lower-fat, higher-carb diet tend to start with lower glucose in the morning and fill up their glucose fuel tanks as the day progresses. As you can see from the higher post-meal glucose values, these people are likely consuming more carbs than they need to. To avoid overfilling their glucose fuel tank, they could dial back the refined carbs later in the day and move more of their calories to earlier in the day when their glucose levels are now.

Balanced Glucose Pattern

As shown in the example below, In time, they can achieve more stable glucose levels across the day without overfilling their glucose fuel tank too often by reflecting on their glucose levels before and after eating and by following the guidance of the DDF app.

Look After the Fuels, and the Hormones Will Look After Themselves

Unfortunately, moderation and balance are boring. They don’t lead to sensational Instagram stories, appealing testimonials, or clickbait headlines! However, it’s the only thing that works long-term.

In the end, the solution to balancing glucagon and insulin problems is pretty simple. To summarise:

- We need enough protein and nutrients from our diet without excess energy.

- Refined carbs raise glucose and insulin quickly, but this is often followed by crashing blood glucose levels and extreme hunger (i.e., reactive hypoglycaemia).

- Fat is not a free food and will keep your blood glucose elevated for longer and keep you from using stored body fat for fuel.

- Excessive high-calorie, low-satiety dietary fat will lead to increased body fat and high insulin levels.

- Moderate amounts of strategic carbs can be helpful to bring your glucose back into the normal range when they drop too low.

- You can use your blood glucose as a fuel gauge to ensure you’re not overfilling your fuel tanks as we do in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges.

- If your goal is fat loss, your glucose works as an excellent fuel gauge to ensure you’re using up your stored energy progressively. In this scenario, insulin falls, and glucagon rises gently to allow your body to access your stored fuel reserves.

- You can use your glucose to ensure your glucose doesn’t fall so low that you trigger your body’s stress response with excessive cortisol and glucagon release and an all-out binge that will put your back on the glucose-insulin-glucagon rollercoaster and drive you to eat more than you need to.

Thank you Marty for such an informative and erudite article.

I wonder whether the role of insulin-glucagon interplay needs emphasis earlier on in your article to emphasis the perhaps paramount importance of this interplay in trying to keep blood sugar levels within strict limits – to avoid excessive blood glucose levels plus to ensure adequate glucose availability for certain areas of the brain, all red blood cells and certain cells of the kidney which are totally dependent on glucose for fuel and thus survival. From my reading of various articles this applies to all humans but as your article informs us especially applies to those of us prone to too low blood glucose levels whether from issues around external insulin use, some blood glucose lowering medication, but in addition reactive hypoglycaemia and inborn errors of metabolism such as certain glycogen storage disease.

I baulk at the traditional education for diabetics in how to combat low blood glucose levels and Peat’s suggestion separate for use of sucrose for fuelling issues – I read that glucose by mouth is less cariogenic than sucrose and there is the issue of fructose intake (from breakdown of sucrose) and effect of frequent fructose boluses in causation of fatty liver, an risk that Professor Lustig mentions forcefully and often !

As a Type One Diabetic for now 56 years I have long bemoaned and other times championed the role of glucagon – and wondered – are there times when I would welcome the use of a glucagon-blocker perhaps safer in a partial blocker form to help prevent overshooting of blood sugar response (after all one would have to do something to dampen the effect of adrenaline on glycogen release too)? This leads to the effect of alcohol on influencing the liver’s ability to release glycogen in response to glucagon increase. Of course beware, that way be dragons!

Thanks for your detailed comment! Great to see you thriving after 56 years with T1D, showing what can be done.

Agree that, while turning off glucagon sounds attractive to manage blood glucose, the resultant rapid obesity and low energy levels (and likely death) would outweigh the improvements on the CGM trace.

RE fructose, I don’t think most people are overeating fruit (it’s the HFCS that’s the biggie). But as you say Lustic and Rick Johnson have been highlighting the issues with high fructose. The problem comes when people follow a guru that tells them that FOOD X is magical and they swing to extremes (e.g. sugar or HEAPS of fruit to ensure your body never needs to engage glucagon) you’re likely going to get into trouble at the other extreme.