- If you are managing diabetes, should you avoid protein because it can convert to glucose and “kick you out of ketosis”?

- If you’ve dropped the carbs and protein to manage your blood sugars, should you eat “fat to satiety” or continue to add more fats until you achieve “optimal ketosis“?

- If adding fat doesn’t get you into the “optimal ketosis zone“, do you need exogenous ketones to get your ketones up so you can start to lose weight?

- And what exactly is a “well-formulated ketogenic diet” anyway?

- the reason that some people may see an increase in their blood sugars and a decrease in their ketones after a high protein meal,

- what it means for their health and

- what they can do to optimise their metabolic health.

What is Gluconeogenesis?

You’re probably aware that protein can be converted to glucose via a process in the body called gluconeogenesis. Gluconeogenesis is the process of converting another substrate (e.g. protein or fat[1]) to glucose.- Gluco = glucose

- Neo = new

- Genesis = creation

- Gluconeogenesis = new glucose creation

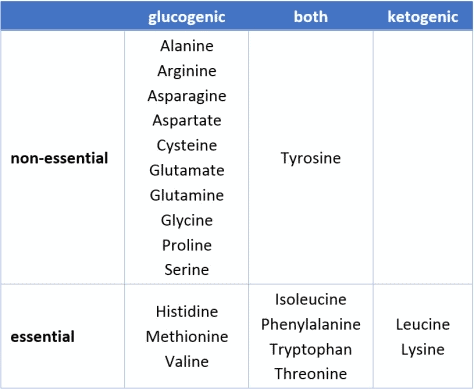

- All but two amino acids (i.e. the micronutrient building blocks that makeup protein) can be converted to glucose.

- Five others can be converted to either glucose or ketones, depending on the body’s requirements at the time.

- Thirteen amino acids can be converted to glucose.

Once your body has used the protein it needs to build and repair muscle and make neurotransmitters, etc. any “excess protein” can be used to refill the small protein stores in the bloodstream and replenish glycogen stores in the liver via gluconeogenesis.

The fact that protein can be converted to glucose is of particular interest to people with diabetes who sometimes go to great lengths to keep their blood sugar under control.[2]

Someone on a very low carbohydrate diet may rely more on protein for glucose via gluconeogenesis compared to someone who can get the glucose they need directly from carbohydrates.[3]

The advantage of obtaining glucose from protein via gluconeogenesis rather than carbs is that it is a slow process and easier to control with measured doses of insulin compared to simple carbs, which will cause more abrupt blood sugar roller coaster.

The food insulin index data[4] [5] [6] is an untapped treasure trove of data that can help us understand the impact of foods on our metabolism.

Once your body has used the protein it needs to build and repair muscle and make neurotransmitters, etc. any “excess protein” can be used to refill the small protein stores in the bloodstream and replenish glycogen stores in the liver via gluconeogenesis.

The fact that protein can be converted to glucose is of particular interest to people with diabetes who sometimes go to great lengths to keep their blood sugar under control.[2]

Someone on a very low carbohydrate diet may rely more on protein for glucose via gluconeogenesis compared to someone who can get the glucose they need directly from carbohydrates.[3]

The advantage of obtaining glucose from protein via gluconeogenesis rather than carbs is that it is a slow process and easier to control with measured doses of insulin compared to simple carbs, which will cause more abrupt blood sugar roller coaster.

The food insulin index data[4] [5] [6] is an untapped treasure trove of data that can help us understand the impact of foods on our metabolism.

Our glucose response to carbohydrate

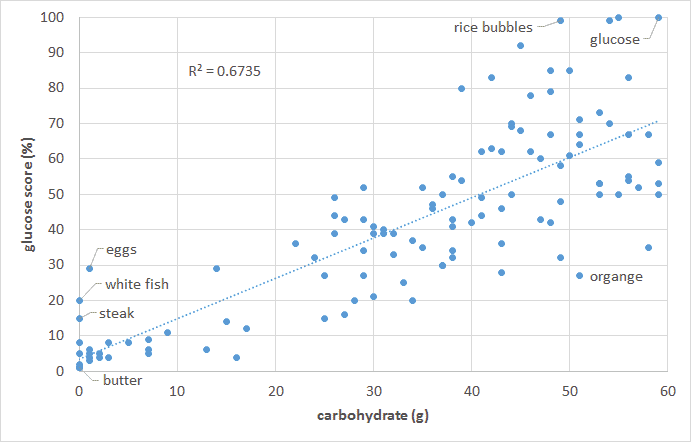

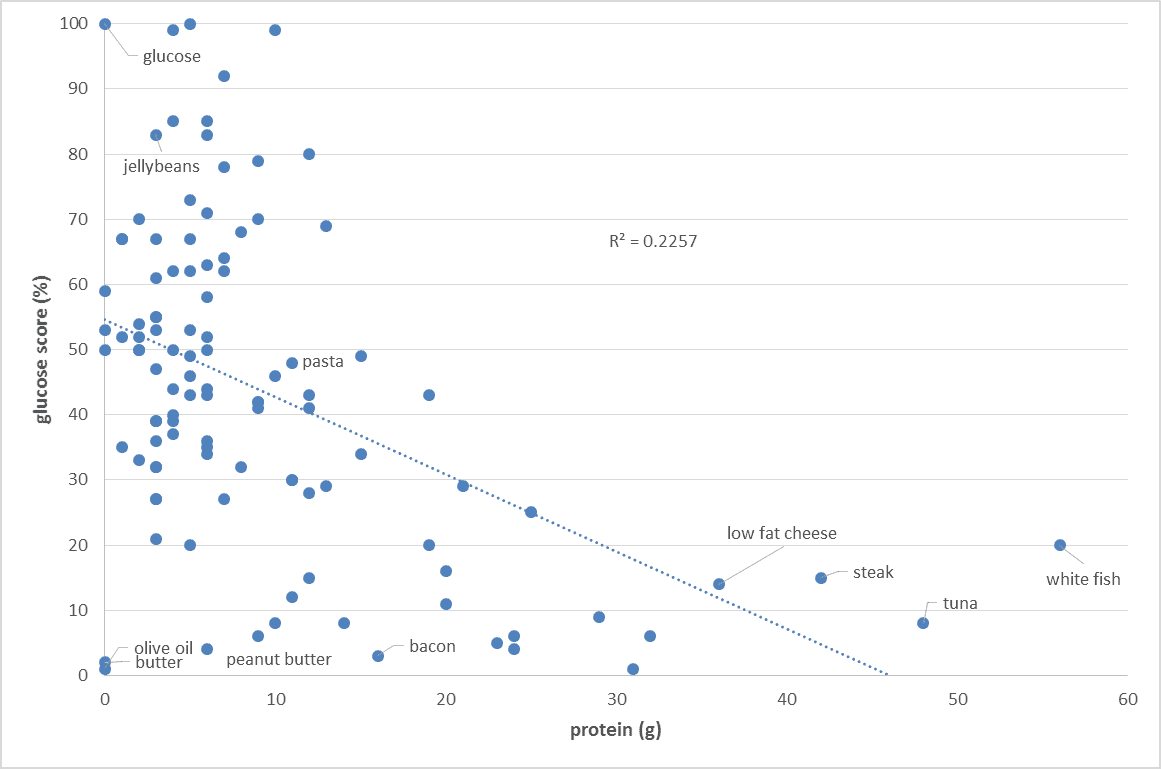

The food insulin index testing measured the glucose and insulin response to various foods in healthy people (i.e. non-diabetic young university students). To calculate the glucose score or the insulin index pure glucose gets a score of 100% while everything else gets a score between zero and 100% based on the comparative glucose or insulin area under the curve response. So we are comparing the glucose and insulin response to various foods to eating pure glucose. As shown in the chart below, the blood glucose response of healthy people is proportional to their carbohydrate intake. Meat and fish and high-fat foods (butter, cream, oil) tend to have a negligible impact on glucose.

Our insulin response to carbohydrates

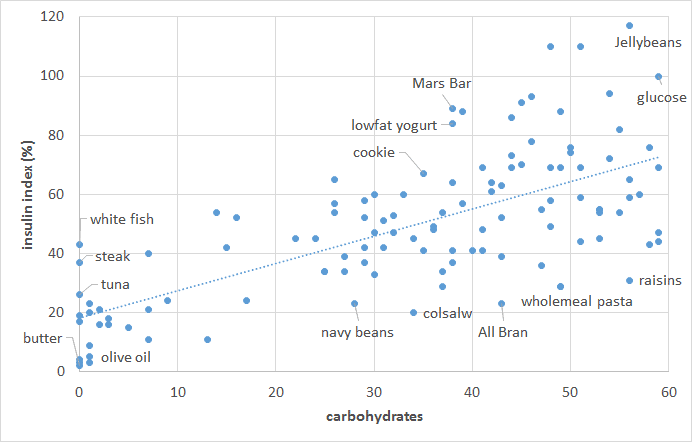

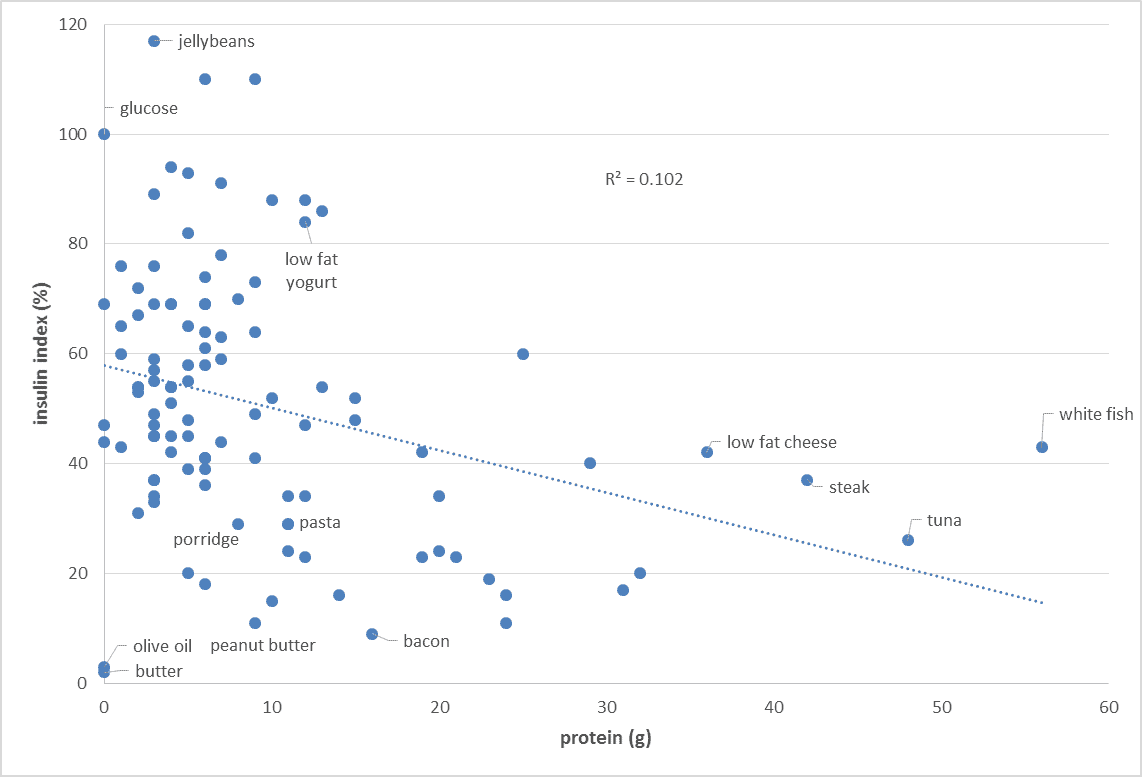

But the story is not as simple when it comes to our insulin response to food. As shown in the chart below, the carbohydrate content of our food only partially predicts our short-term insulin response to food. Low-fat, low-carb, high-protein foods elicit a significant insulin response. As you can see in the chart below, once we account for protein, we get a better prediction of our insulin response to food. It seems we require about half as much insulin for protein as we do for carbohydrate.

As you can see in the chart below, once we account for protein, we get a better prediction of our insulin response to food. It seems we require about half as much insulin for protein as we do for carbohydrate.

But does this mean we should avoid or minimise protein for optimal diabetes management or weight loss? Does protein immediately turn to chocolate cake in our bloodstream?

But does this mean we should avoid or minimise protein for optimal diabetes management or weight loss? Does protein immediately turn to chocolate cake in our bloodstream?

What happens to insulin and blood sugar when we eat more protein?

While protein does generate an insulin response, increasing the protein content of our food typically decreases our insulin response to food. Increasing protein generally forces out processed carbs from our diet and improves the amount of vitamins and minerals contained in our food.[7] Similarly, increasing the protein content of your food will also decrease your glucose response to food.

Increasing protein generally forces out processed carbs from our diet and improves the amount of vitamins and minerals contained in our food.[7] Similarly, increasing the protein content of your food will also decrease your glucose response to food.

What happens when you eat a big protein meal?

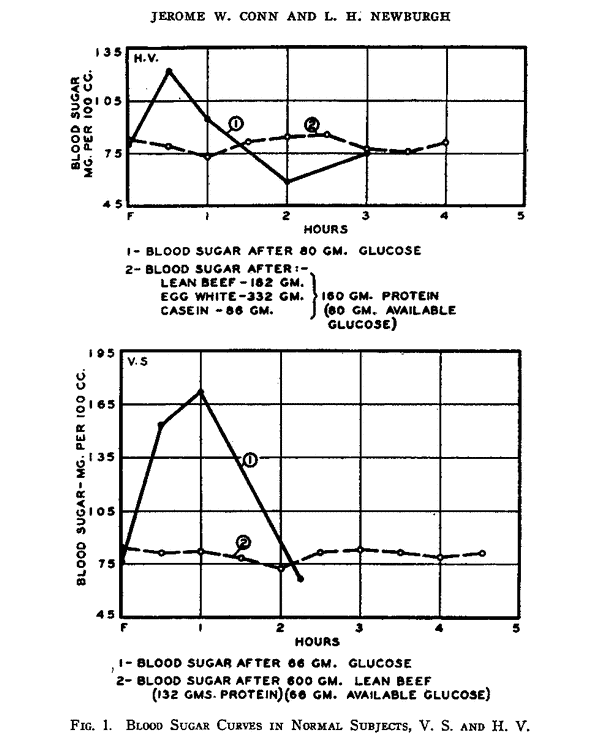

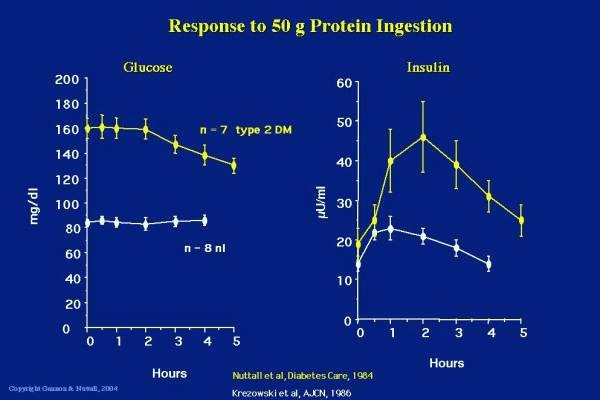

The food insulin index testing was done using 1000 kJ or 240 calories of each food (i.e. a substantial snack, not a full meal). But what about if we ate a LOT of protein? Wouldn’t we get a blood sugar response then? The figure below shows the glucose response to 80g of glucose vs. 180g of protein (i.e. a MASSIVE amount of protein). While we get a roller coaster-like blood sugar rise in response to the ingestion of glucose, blood sugar remains relatively stable in response to the large protein meal.[8] [9] [10] So, if the protein can turn to glucose, why don’t we see a massive glucose spike?

What is going on?

So, if the protein can turn to glucose, why don’t we see a massive glucose spike?

What is going on?

The role of insulin and glucagon in glucose control

To properly understand how we process protein, it’s critical to understand the role of the hormones insulin and glucagon in controlling the release of glycogen release from our liver. These terms can be confusing. So let me spell it out.- The liver stores glucose in the form of glycogen in the liver.

- Glucagon is the hormone that pushes glycogen into the bloodstream as blood glucose.

- Insulin is the opposing hormone that keeps glycogen stored in our liver.

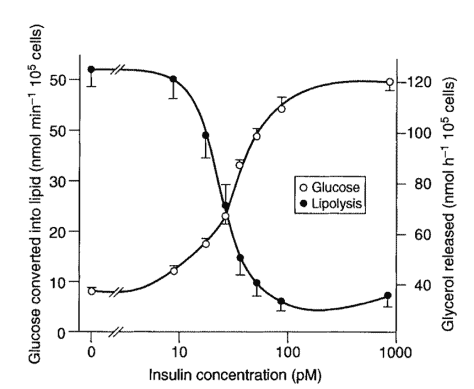

When our blood glucose is elevated, or we have external sources of glucose, the pancreas secretes insulin to shut off the release of glycogen from the liver until we have used up or stored the excess energy.

Insulin helps to turn off the flow of glucose from our liver and store some of the excess glucose in the blood as glycogen and, to a much lesser extent, fat (via de novo lipogenesis). It also tells the body to start using glucose as its primary energy source to decrease it to normal levels.

When our blood glucose is elevated, or we have external sources of glucose, the pancreas secretes insulin to shut off the release of glycogen from the liver until we have used up or stored the excess energy.

Insulin helps to turn off the flow of glucose from our liver and store some of the excess glucose in the blood as glycogen and, to a much lesser extent, fat (via de novo lipogenesis). It also tells the body to start using glucose as its primary energy source to decrease it to normal levels.

We can push the glucagon pedal to extract the glycogen stores in our liver by eating less carbohydrate (i.e. low carb or keto diets), eating less, or not eating at all (aka fasting)!

Higher insulin levels effectively mean that we have enough fuel in our bloodstream, and we need to put down the fork.

While fat typically doesn’t require significant amounts of insulin to metabolise, an excess of energy from any source will cause the body to ramp up insulin to shut off the release of stored energy from the liver and the fat stores.

We can push the glucagon pedal to extract the glycogen stores in our liver by eating less carbohydrate (i.e. low carb or keto diets), eating less, or not eating at all (aka fasting)!

Higher insulin levels effectively mean that we have enough fuel in our bloodstream, and we need to put down the fork.

While fat typically doesn’t require significant amounts of insulin to metabolise, an excess of energy from any source will cause the body to ramp up insulin to shut off the release of stored energy from the liver and the fat stores.

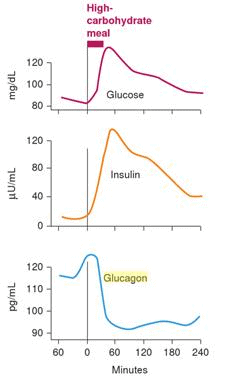

Glucose, insulin and glucagon response to a high carbohydrate meal

At the risk of getting a little bit geeky, let’s look at how our hormones respond to different types of meals. As shown in the chart below, when we eat a high carbohydrate meal, insulin rises to stop the release of glycogen. Meanwhile, glucagon drops to stop stimulating the release of glycogen from the liver. When we have enough incoming glucose via our mouth, we don’t need any more glucose from the liver.[11]

Glucose, insulin and glucagon response to a high protein meal

When we eat a high protein meal, both glucagon and insulin rise to maintain steady blood glucose levels while promoting the storage and use of protein to repair our muscles and organs and make neurotransmitters, etc. (i.e. important stuff!). In someone with a healthy metabolism, we see a healthy balance between insulin (brake) and glucagon (accelerator). Hence, we don’t get any glycogen released from the liver into the bloodstream to raise our blood sugar because the insulin from the protein turns off the glucose from the liver.

This is why metabolically healthy people see a flat-line blood sugar response to protein.

In someone with a healthy metabolism, we see a healthy balance between insulin (brake) and glucagon (accelerator). Hence, we don’t get any glycogen released from the liver into the bloodstream to raise our blood sugar because the insulin from the protein turns off the glucose from the liver.

This is why metabolically healthy people see a flat-line blood sugar response to protein.

Insulin response to protein for people with diabetes

Things are different if you have diabetes. Insulin resistance means that things don’t work as smoothly between our fatty liver and insulin-resistant adipose tissue. While your blood sugar may rise or fall in response to protein, your insulin needs to increase a lot more while you metabolise the protein to build muscle and repair your organs. Unfortunately, people who are insulin resistant may struggle to build muscle effectively due to insulin resistance. Then the higher levels of insulin may drive them to store more fat in the process.[12] Becoming insulin sensitive is important! The chart below shows the difference in the blood glucose and insulin response to protein in a group of people who are metabolically healthy (white lines) versus people who have type 2 diabetes (yellow lines).[13] People with diabetes may see their glucose levels drop from a high level after a large protein meal and will have a much greater insulin response due to their insulin resistance. People with more advanced diabetes (i.e. beta cell burnout or Type 1 diabetes) may even see their blood sugar rise. Their ability to produce insulin to metabolise the protein and keep glycogen in storage cannot keep up with the demand.

Drawing on the brake/accelerator analogy, it’s not necessarily protein turning into glucose in the bloodstream via gluconeogenesis, but rather the glucagon kicking in and a sluggish insulin response that isn’t able to balance out the glucagon response to keep the glycogen locked away in the liver.

Healthy people will be able to balance the opposing hormonal forces of the insulin (brake) and the glucagon (accelerator), but if we are insulin resistant and don’t have a properly functioning pancreas (brake), we won’t be able to produce as much insulin to balance the glucagon response.

Someone who is insulin resistant has a functioning accelerator pedal (glucagon stimulating glucose release in the blood) but a faulty brake (insulin).

People with diabetes may see their glucose levels drop from a high level after a large protein meal and will have a much greater insulin response due to their insulin resistance. People with more advanced diabetes (i.e. beta cell burnout or Type 1 diabetes) may even see their blood sugar rise. Their ability to produce insulin to metabolise the protein and keep glycogen in storage cannot keep up with the demand.

Drawing on the brake/accelerator analogy, it’s not necessarily protein turning into glucose in the bloodstream via gluconeogenesis, but rather the glucagon kicking in and a sluggish insulin response that isn’t able to balance out the glucagon response to keep the glycogen locked away in the liver.

Healthy people will be able to balance the opposing hormonal forces of the insulin (brake) and the glucagon (accelerator), but if we are insulin resistant and don’t have a properly functioning pancreas (brake), we won’t be able to produce as much insulin to balance the glucagon response.

Someone who is insulin resistant has a functioning accelerator pedal (glucagon stimulating glucose release in the blood) but a faulty brake (insulin).

Real-life example

To unpack this further, let’s look at an example close to home. The picture below is of a family meal (i.e. steak, sauerkraut, beans and broccoli) that we had when my wife Monica (who has Type 1 Diabetes) was wearing a continuous glucose meter. The photo of the continuous glucose monitor below shows Monica’s blood sugar response after the meal which we had at about 5:30 pm. Her blood sugar rises in response to the veggies and then comes back down as the insulin kicks in.

The photo of the continuous glucose monitor below shows Monica’s blood sugar response after the meal which we had at about 5:30 pm. Her blood sugar rises in response to the veggies and then comes back down as the insulin kicks in.

The process to bring her blood sugars back under control from a few carbs in the veggies takes about two hours.

But over the next twelve hours, Monica’s blood sugar level drifts up as the insulin dose goes to work as she metabolises the protein. For all intents and purposes though it looks like the protein is turning to glucose in her blood!

The process to bring her blood sugars back under control from a few carbs in the veggies takes about two hours.

But over the next twelve hours, Monica’s blood sugar level drifts up as the insulin dose goes to work as she metabolises the protein. For all intents and purposes though it looks like the protein is turning to glucose in her blood!

This is not a one-off occurrence. We’ve seen this blood glucose response regularly, particularly to a large steak meal! The advent of continuous glucose meters makes this more evident as you can watch blood sugars rise over a long period after a high protein meal.

Many people with type 1 diabetes know they need to dose with insulin for protein. Once you work out how to reduce simple carbs, working out how to dose for protein is the next frontier of insulin management.

It can be complicated and sometimes confusing.

This is not a one-off occurrence. We’ve seen this blood glucose response regularly, particularly to a large steak meal! The advent of continuous glucose meters makes this more evident as you can watch blood sugars rise over a long period after a high protein meal.

Many people with type 1 diabetes know they need to dose with insulin for protein. Once you work out how to reduce simple carbs, working out how to dose for protein is the next frontier of insulin management.

It can be complicated and sometimes confusing.

More insulin or less protein?

So, what is the problem here? Why are Monica’s blood sugars rising? Is it too much protein? Or not enough insulin? I think the best way to explain the rise in blood sugars is that there is not enough insulin to keep the glycogen locked away in her liver and metabolise the protein to build muscle and repair her organs at the same time. Meanwhile, the glycogen pedal is pushed down as it normally would be in response to a protein which is driving the glucose up in her bloodstream. There is not enough insulin in the gas tank (pancreas) to do everything that needs to be done. So, if Monica had a choice, should she:- A. Keep her blood sugars stable and stop metabolising protein to repair her muscles and organs,

- B. Metabolise protein to build her muscles and repair her organs while letting her blood sugars drift up, or

- C. Both of the above.

A lot of my initial motivation in developing the Optimising Nutrition blog was to understand which foods provoked the least insulin response and how to more accurately calculate insulin dosing for people with diabetes to help Monica get off the blood glucose roller coaster. Like Ted Naiman, I thought if we reduced the insulin load from our food (including minimising protein), we would have a pretty good chance of losing a lot of weight (just like someone with uncontrolled type 1 diabetes).One source of protein loss is hepatic gluconeogenesis, whereby amino acids are used to produce glucose. This is inhibited by insulin, as is the breakdown of muscle proteins to release amino acids, and therefore occurs mainly during periods of fasting (or low carb).

However, inhibition of gluconeogenesis and protein catabolism is impaired when insulin release is abnormal, insulin resistance occurs, or when circulating levels of free fatty acids in the blood are high. These are interdependent conditions that are associated with overweight and obesity, and are especially pronounced in type 2 diabetes (12,34).

It might be predicted that the result of higher rates of hepatic gluconeogenesis will be an INCREASED requirement for protein in the diet.

I no longer think we need to restrict or avoid protein to manage insulin resistance. However, there’s no need to go to the other extreme and binge on protein if you are injecting insulin.

Worrying about getting too little or too much protein is largely irrelevant. We will get enough protein when we eat a nutritious diet. Left to its own devices, our appetite typically does an excellent job of seeking out adequate protein to suit our current needs.

Meanwhile, actively aiming to minimise protein will make it harder to maintain lean muscle mass, which is critical to glucose disposal and insulin sensitivity.

I no longer think we need to restrict or avoid protein to manage insulin resistance. However, there’s no need to go to the other extreme and binge on protein if you are injecting insulin.

Worrying about getting too little or too much protein is largely irrelevant. We will get enough protein when we eat a nutritious diet. Left to its own devices, our appetite typically does an excellent job of seeking out adequate protein to suit our current needs.

Meanwhile, actively aiming to minimise protein will make it harder to maintain lean muscle mass, which is critical to glucose disposal and insulin sensitivity.

If you see your blood sugar levels rise due to protein, it is likely due to the inability to produce enough insulin rather than too much protein. If you are injecting insulin, you may need to dose with more insulin to allow you to utilise the protein in your diet to build and repair your body.

If you see your blood sugar levels rise due to protein, it is likely due to the inability to produce enough insulin rather than too much protein. If you are injecting insulin, you may need to dose with more insulin to allow you to utilise the protein in your diet to build and repair your body.

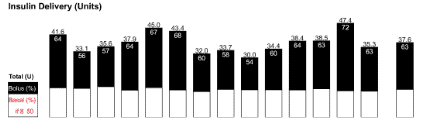

Basal and bolus insulin

One option to minimise the adverse effects of excess insulin is to focus on reducing the insulin load of our diet and eat only high-fat foods that have a low proportion of insulinogenic calories (i.e. ones towards the bottom left of this chart). If you are highly insulin resistant and obese, this will work like magic, at least for a little while.

People who suddenly stop eating processed junk carbs and eat more fat often find that their appetite plummets as the insulin demand of their food drops and they are more easily able to access their own body fat.[14] [15]

But this is only part of the story. Again, we can learn a lot about insulin from people with Type 1 diabetes who have to manually manage their insulin dose.

In diabetes management, there are two kinds of insulin doses:

If you are highly insulin resistant and obese, this will work like magic, at least for a little while.

People who suddenly stop eating processed junk carbs and eat more fat often find that their appetite plummets as the insulin demand of their food drops and they are more easily able to access their own body fat.[14] [15]

But this is only part of the story. Again, we can learn a lot about insulin from people with Type 1 diabetes who have to manually manage their insulin dose.

In diabetes management, there are two kinds of insulin doses:

- basal insulin, and

- bolus insulin.

In someone following a low carb diet, only around 30% of the insulin is for the food, and 70% is basal insulin as shown below in my wife Monica’s daily insulin dose shown below.

In someone following a low carb diet, only around 30% of the insulin is for the food, and 70% is basal insulin as shown below in my wife Monica’s daily insulin dose shown below.

We can only reduce our insulin requirements marginally by changing our diet and reducing the amount of body fat we are trying to hold in storage. We always need some basal insulin. If we’re insulin resistant and carrying more body fat, we’ll need more insulin.

We can only reduce our insulin requirements marginally by changing our diet and reducing the amount of body fat we are trying to hold in storage. We always need some basal insulin. If we’re insulin resistant and carrying more body fat, we’ll need more insulin.

How to improve your basal insulin sensitivity

In addition to modifying our diet, we can also improve our blood glucose control by maximising our body’s ability to dispose of glucose without relying on insulin (i.e. non-insulin mediated glucose uptake). We enhance our insulin sensitivity and our ability to use glucose by building more lean muscle mass. I used to think that if we just dropped the insulin load of our diet down far enough, we would be able to lose weight, a bit like someone with uncontrolled type 1 diabetes. But now I understand that there will always be enough basal insulin in our system to store excess energy (regardless of the source) and stop our liver from releasing stored energy. While a person with diabetes can reduce their insulin requirements for food by eating food with lots of fat, they can actually end up insulin resistant and need more basal insulin if they drive overabundance of energy, regardless of whether it’s from protein, fat or carbs.[16] While ketones can rise to quite high levels when fasting (which is fine), I fear that some people are chasing high ketone levels with lots of dietary fat and the excess energy may lead to insulin resistance in the long term.

Dr Bernstein Diet Approach

The method recommended by Dr Bernstein (who has type 1 diabetes himself) is typically lower in carbs, adequate protein (depending on whether you are a growing child) and moderate in fat. Even at 83 years of age, Dr B feels it is essential to maintain lean muscle mass through regular exercise to maximise his insulin sensitivity.

Even at 83 years of age, Dr B feels it is essential to maintain lean muscle mass through regular exercise to maximise his insulin sensitivity.

Will too much protein “kick me out of ketosis”?

While the ketogenic diet is becoming popular, I think most people who are interested in it do not necessarily require therapeutic ketosis, but rather are chasing weight loss or blood sugar control/diabetes management. If you are managing a condition that benefits from high levels of ketosis (e.g. epilepsy, dementia, cancer, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s) then limiting protein may be necessary to ensure continuously elevated ketone levels and reduce insulin to avoid driving growth in tumour cells and cancer.

Giving the burgeoning interest in the ketogenic dietary approach, it’s important to understand the difference between exogenous ketosis and endogenous ketosis.

If you are managing a condition that benefits from high levels of ketosis (e.g. epilepsy, dementia, cancer, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s) then limiting protein may be necessary to ensure continuously elevated ketone levels and reduce insulin to avoid driving growth in tumour cells and cancer.

Giving the burgeoning interest in the ketogenic dietary approach, it’s important to understand the difference between exogenous ketosis and endogenous ketosis.

- Endogenous ketosis occurs when a person eats less than the body needs to maintain energy homeostasis and we are forced to up the glycogen in our liver and then our body fat to make up the difference.

- Exogenous ketosis (or nutritional ketosis) occurs when we eat lots of dietary fat (or take exogenous ketones), and we see blood ketones (beta-hydroxybutyrate) build up in the blood. We are burning dietary fat for fuel.

| Endogenous ketosis | Exogenous ketosis |

| Low total energy (i.e. blood glucose + blood ketones + free fatty acids) | High total energy (i.e. blood glucose + blood ketones + free fatty acids) |

| Stored energy taken from body fat for fuel | Ingested energy used preferentially as fuel |

| Stable ketone production all day | Sharp rise of ketones for a short duration. Need to keep adding fat or exogenous ketones to maintain elevated ketones. |

| Insulin levels are low which allows the release of glycogen from our liver and fat stores | Insulin levels increase to hold glycogen in liver and fat in adipose tissue |

| Mitochondrial biogenesis, autophagy, increase in NAD+, increase in SIRT1 | Mitochondrial energy overload, autophagy turned off, decrease in NAD+ |

| Body fat and liver glycogen used for fuel | Liver glycogen refilled and excess energy in the bloodstream stored as fat. |

Summary

- Gluconeogenesis is the creation of new glucose (generally from protein).

- Protein requires about half as much insulin as carbohydrate to metabolise.

- Increasing protein intake will generally improve our blood glucose and insulin levels. Protein forces out processed carbohydrates, increasing the nutritional quality of our diet and helps us to build muscle, which in turn burns glucose more efficiently.

- In a metabolically healthy person, glucagon balances the insulin response to protein, so we see a flat line blood sugar response to even a large protein meal.

- If you cannot produce enough insulin, you may see glucose rise as your body tries to metabolise the protein and keep the energy stored in the liver at the same time.

- The insulin for the food we eat (bolus) represents less than half of our daily insulin demand. We can improve our basal insulin sensitivity by building lean muscle mass and improving mitochondrial function via a nutrient-dense diet.

- If we are aiming for weight loss and health, then low blood sugars and low ketones will be more desirable rather than chasing high ketone levels via exogenous ketosis.

Read more about the Food Insulin index

- Making sense of the Food Insulin Index

- Does Protein Spike Insulin (and Does It Matter)?

- What foods raise your blood sugar and insulin levels (other than carbs)?

- The insulin load… the greatest thing since carb counting!

- Does protein raise blood sugar?

- The blood glucose, glucagon and insulin response to protein

- Insulin calculator for Type 1 Diabetes (including protein and fibre)

- What is the difference between glycemic index, the insulin index and insulin load?

- Nutrient-dense foods for stable blood sugars and nutritional ketosis

references

[1] http://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002116 [2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3636610/ [3] https://optimisingnutrition.com/2015/06/04/the-goldilocks-glucose-zone/ [4] https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/11945 [5] https://optimisingnutrition.com/2015/03/23/most-ketogenic-diet-foods/ [6] https://optimisingnutrition.com/2015/03/30/food_insulin_index/ [7] https://optimisingnutrition.com/2017/05/27/is-there-a-relationship-between-macronutrients-and-diet-quality/ [8] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16694439 [9] http://caloriesproper.com/dietary-protein-does-not-negatively-impact-blood-glucose-control/beef-vs-glucose/ [10] http://www.ketotic.org/2013/01/protein-gluconeogenesis-and-blood-sugar.html#¹ [11] https://books.google.com.au/books?id=3FNYdShrCwIC&printsec=frontcover&dq=marks+basic+medical+biochemistry&hl=en&sa=X&ei=-ctaVcivOJfq8AXL84CAAw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=glucagon&f=false [12] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4997013/ [13] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC524031/ [14] https://docmuscles.com/ [15] https://optimisingnutrition.com/2017/01/15/how-optimize-your-diet-for-your-insulin-resistance/ [16] https://nutritionandmetabolism.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1743-7075-11-23

post last updated July 2019

Thank you very much. You just solved my biggest puzzle.

Great article Marty. I think this statement from the article is not quite right.

“The net result is that we have the brake and the accelerator on at the same time so we don’t get any glycogen released from the liver into the bloodstream to raise our blood sugar because the insulin from the protein is turning off the glucose from the liver.”

The following is from Guyton’s Textbook Of Medical Physiology 11th edition,

“Increased Blood Amino Acids Stimulate Glucagon Secretion.

High concentrations of amino acids, as occur in the blood after a protein meal (especially the amino acids alanine and arginine), stimulate the secretion of glucagon. This is the same effect that amino acids have in stimulating insulin secretion. Thus, in this instance, the glucagon and insulin responses are not opposites. The importance of amino acid stimulation of glucagon secretion is that the glucagon then promotes rapid conversion of the amino acids to glucose, thus making even more glucose available to the tissues.”

It is true that amino acids from the breakdown of dietary protein stimulates both insulin secretion and glucagon secretion. However, the “purpose” of the glucagon secretion is to stimulate liver gluconeogenesis to prevent hypoglycemia. If a normal person were to eat a steak without any carbohydrate and only insulin were secreted, hypoglycemia would result. The glucagon thus serves to prevent hypoglycemia. In a person with type 1 diabetes (T1DM), eating a steak has the same effect of stimulating glucagon and if the exogenous bolus and/or basal insulin doses are not quite enough, then hyperglycemia can result. Of course, if the insulin doses are just right, normoglycemia follows ingestion of the steak, or if too much insulin is given, hypoglycemia results. I agree restricting dietary protein to the point that muscle/protein synthesis is impaired is not a good idea. Persons with T1DM just have to tinker with the insulin doses to “cover” dietary protein. At least dietary protein requires a lot less insulin than dietary carbohydrate. In reality however, we rarely eat meals of just one macronutrient. Thus, the exogenous insulin given in those with T1DM needs to be “just right” to compensate for the protein, carbohydrate, and fat in the meal. To make matters more complicated, there are other factors besides the macronutrients that make this balancing act difficult including variable absorption of insulin from the injection or infusion site, variable absorption of the macronutrients eaten, and variable insulin sensitivity related to physical activity.

Keep up the good work Marty. Your work is particularly helpful to those of us with diabetes.

Thanks Kieth!

Very comprehensive article Marty, good stuff.

I second Keith’s comment. See minute 18 on of Roger Unger’s talk on T1D/T2Ds https://youtu.be/VjQkqFSdDOc?t=18m. Not only does insulin absorption matter as Keith pointed out, so does where it’s injected and it’s concentrations across different tissues. Endogenous insulin concentrations go from about 2,000 (pancreas) to 50 (liver) to 5 uU/mL (skeletal muscle) whilst injected insulin doesn’t follow this heterogenous patterns (it’s way more homogeneous unfortunately).

Also, some (at the very least small) amount of protein always turns to glucose if I recall correctly.

I think the question we should be asking is How do we suppress glucagon without insulin (marginal returns as the dosage increases)? Some suggest Somatostatin (or look at it, as George Henderson has).

Amazing blog post, things are really coming together with your hard work, thanks for this amazing blog post.

thanks Simon. great to see them getting a good response. they take a good chunk of time! 🙂

Wonderful post!! So clear and easy to understand for such a complicated subject.

Thanks heaps. There is a lot of confusion here!

This post is tremendously helpful, Thankyou

Cheers. Thanks.

Thank you, Marty Kendall, for this excellent article. I have just been reading the book, ‘The Nature of Nutrition’ which puts forth the Protein Leverage Hypothesis. I was fascinated to learn that not eating a sufficient amount of protein (i.e., the amount that your body needs) will cause increased appetite and will lead to you to overeat fats and carbs (as your body seeks to get the protein it needs from other sources). So according to these authors (whom you reference in your article), adequate protein is tremendously important, and different conditions (in addition to diabetes) change the protein need (even being sedentary does this). At the same time, it’s not good to eat too much protein, because excess protein is aging and will shorten lifespan (that’s the simple version of the authors’ argument). Anyway, I’m fascinated by the Protein Leverage Hypothesis. All very interesting and very complicated!

A most comprehensive, detailed explanation regards protein ingestion & diabetes. A godsend; thank you! (:

Thanks. I’m so glad people find it helpful!

Great article! I have a question. If your post prandial (2h) blood sugar is relatively stable (<100) after a large protein meal (120g+), but morning blood sugar is high on waking, does that imply an issue with insulin sensitivity or not? The PP reading would seem to be most important, but I am finding elevated morning readings whilst experimenting with zero carb eating.

Can you finish your question Ben?

Hi, I am trying to understand if the morning FBS being higher on a intermittently Ketogenic zero carb diet ( some days very high protein ie 250g, others closer to 100) is a cause for concern or not. I still see ketones in the .3-1.0 range but often along with higher FBS (95-110)then when I was strictly VLCKD (<75).

I’m confused. It sounds as if endogenous ketones aren’t healthy – it’s the produce of starving the body. As a result if you have low energy then how can that be optimal?

On the other hand if you eat a lot of dietary fat (as many keto people advocate) then you don’t lose weight.

Ketones are great and natural. Having high levels of glucose and ketones at the same time isn’t.

Hi Marty, great in-depth article, as usual. one doubt, not necessarily diabetes related;

would the benefits of the ketogenic diet diluted when higher protein intakes (higher than 1 to 2g*kg ideal weight) raise blood glucose ranges to the 80s-100s mg/dL range (which are often around the 60s-70s range on strictly lower protein intakes, around 0.8g*kg ideal weight)?

would those BG ranges (80s-100smg/dL) be considered “a high glucose high ketone state”, provided a low carb regimen is being followed?

thanks in advance!!

Low blood glucose is ultimately about low energy, so higher protein could be beneficial if it leads to higher satiety and high glucose could occur from high fat which could lead to poor satiety.

I would go for the higher protein intake and the normal blood sugars rather than super low blood sugars and high ketones. Unless you are managing something like epilepsy or dementia, I think the ‘benefits of a ketogenic diet is the stable blood sugars.

Check out the blood sugar ranges in this post. https://optimisingnutrition.com/2015/07/20/the-glucose-ketone-relationship/

Thank you, Marty. As a LCHP/keto follower myself, I am finding this information useful in crafting the healthiest diet for my newly-diagnosed diabetic dog. It is very helpful for both of us!