Menopause—the cessation of monthly hormone cycles, bleeding (menses), and egg releases (ovulation) that often occurs in a woman’s forties and fifties—is often met with dread.

The hormone changes during a woman’s transition into menopause (i.e., perimenopause) cause mood swings, changes in body temperature, unpredictable bleeding, energy fluctuations, and ever-feared weight gain.

Understanding and addressing menopausal weight gain is a hot topic for many in our Optimising Nutrition community, so I’ve been eager to delve into it for a while.

Building on recent research, this article will delve into what happens after and how you can prepare for this transition.

In this article, we’ll discuss what menopause means from a physiological standpoint, how it can affect your body, and how you can optimise your nutrition and lifestyle to crush menopause.

- Why Do Women Gain Weight During Menopause?

- Protein Leverage

- How to Prevent Menopausal Weight Gain

- What Are-Higher Protein % Foods and Meals?

- How to Identify the Right Balance of Protein vs Fat and Carbs for YOU

- The Basics of the Female Hormonal Cycle

- What Changes Occur During Menopause?

- What Is the Average Weight Gain During Menopause?

- Why Am I Gaining Weight So Fast During Menopause?

- Andropause in Men

- Extended Fasting and Aggressive Dieting

- Is Fasting Good for Someone in Menopause?

- What Is the Best Form of Exercise to Mitigate Menopausal Weight Gain?

- Why Does Bone Density Decrease in Menopause?

- How Can I Improve Bone Density Before Menopause?

- How Can I Prevent Bone Density Loss in Menopause?

- Mood Changes During Menopause

- How Do I Prevent or Avoid the Psychological Changes of Menopause?

- Where Do I Start?

- Summary

- More

Why Do Women Gain Weight During Menopause?

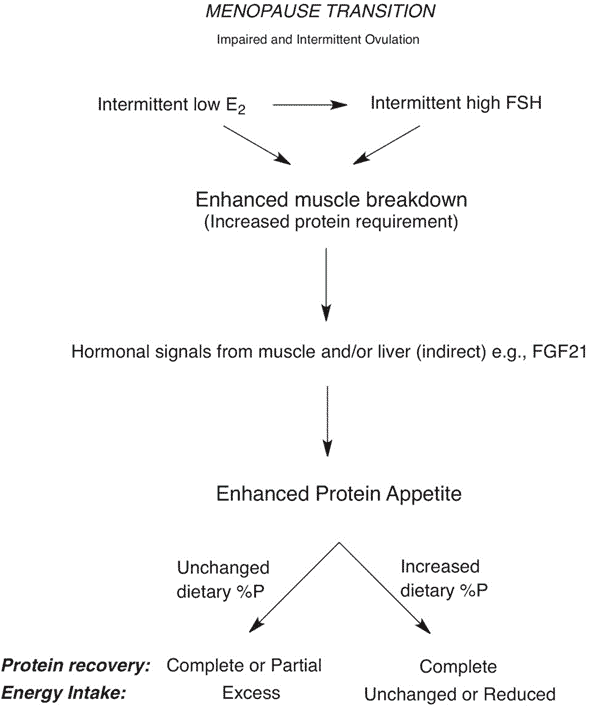

University of Sydney Professors David Raubenheimer and Stephen Simpson recently released a study, Weight gain during the menopause transition: evidence for a mechanism dependent on protein leverage, in the journal Obstetrics & Gynaecology that elegantly outlined the mechanism and solution to menopausal weight. We’ve included the main chart from their pre-print manuscript below.

To summarise:

- A reduction in estrogen and high follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and increased anabolic resistance and insulin resistance in women as we age lead to a loss of lean mass. While anabolic and insulin resistance occur in men, too, menopause accelerates this process in females.

- In an effort to compensate for the loss of muscle, our bodies seek more protein by eliciting cravings for more of it.

- Activity levels often also decrease as we age, so we require less energy from food.

- We consume more food to get the protein we require and gain weight if we don’t change what we eat during this transition.

Protein Leverage

Raubenheimer and Simpson’s previous work on protein leverage elegantly explains the weight gain that occurs during menopause for women and andropause for men.

Protein leverage has been observed in many organisms, including humans. Any living being eats until it gets the required protein, even if that means consuming more energy than requierd. You can learn more in my chat with them here.

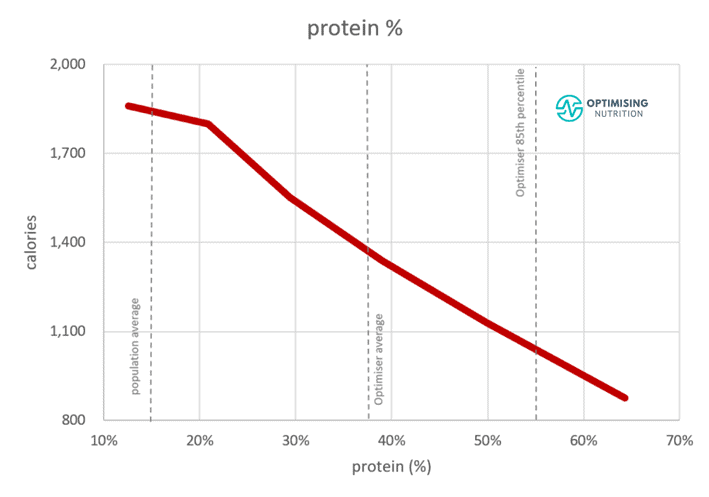

The chart below shows protein % vs calorie intake from our analysis of one hundred and fifty thousand days of data from forty thousand Optimisers. While satiety is multifactorial, protein %—or the per cent of total calories we consume from protein—significantly impacts how much we eat.

How to Prevent Menopausal Weight Gain

In their recent menopause paper, Raubenheimer and Simpson highlight the elegant solution to reverse this all-too-common trend of menopausal weight gain.

While muscle breakdown can be partially mitigated with estrogen replacement therapy, changing what we eat by increasing the per cent of our total calories from protein is also critical.

To increase your protein %, you must dial back energy from fat and carbs while prioritising protein.

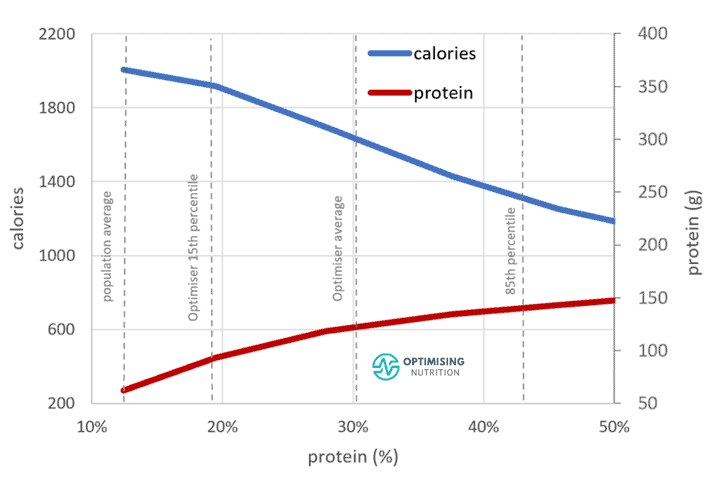

As shown in the chart below from our Optimiser data analysis, the additional quantity of protein (in grams) we require tends to be minimal. However, the change in energy intake that aligns with a small change in protein % can be quite large.

Being more physically active is also helpful because it allows us to eat more, which gives us the chance to get more nutrients like protein. But if you can’t exercise, you may need to dial up protein % a little more. The charts below from their paper show some scenarios to demonstrate how this works.

- The scenario on the left shows what to do when activity levels do not decrease with age. Protein intake only needs to increase slightly, from 85 to 91 g per day. This is accompanied by a reduction of around 153 calories from carbs or fat, slightly increasing your protein % from 16 to 17%.

- The scenario on the right shows the changes we can expect to make if we’re less active. Here, we require a more substantial reduction in calories from carbs and fat, which increases our protein % even more, from 16 to 19%.

This is the exact process we follow in our Macros Masterclass. While you may think it’s the lean and active bros that need more protein, it’s always the older, post-menopausal females that tend to thrive on a higher protein %. This is because they tend to be smaller, have less muscle mass, and require less energy.

People who are lean and young, with healthy hormone levels, don’t need to worry much about their protein intake. They also tend to be active and use more energy, so it’s easy to get enough protein.

However, as we age, we are less active, anabolic hormones decrease, and insulin resistance increases; we need to pay more attention to getting adequate protein in our decreasing energy budget.

What Are-Higher Protein % Foods and Meals?

In consultation, advisory groups highlighted to the researchers that ‘many women would be unable to identify high or low-protein foods’ to prioritise or avoid.

While the problem and the solution are elegantly simple, it’s not easy to overcome habits and instincts that lead us to lower-protein, energy-dense foods.

Foods With a Higher Protein %

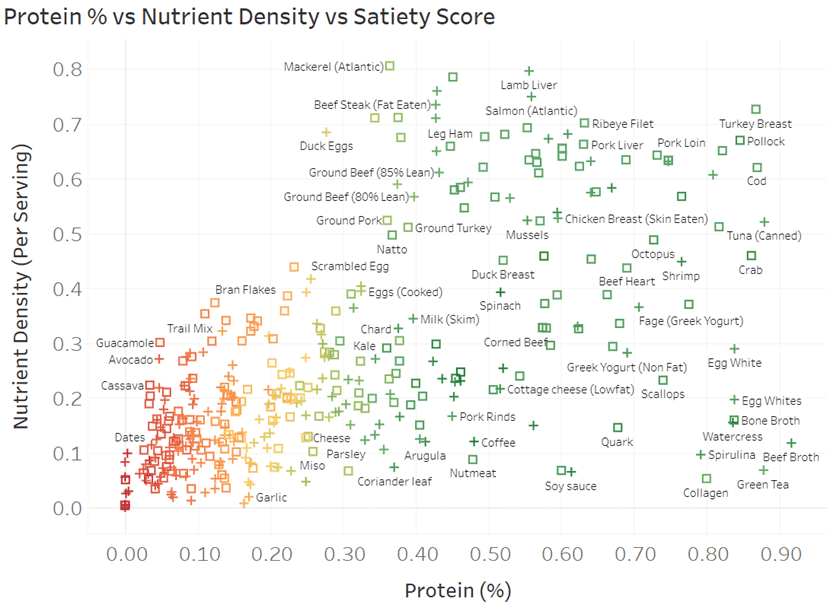

To help you identify foods that contain more protein and less energy from fat and carbs, the chart below shows popular foods in terms of protein % vs nutrient density. For more detail, you can view the interactive Tableau version here.

- To increase protein %, you should target more foods toward the right.

- To maximise nutrients per serving, you should prioritise foods towards the top.

- The colour codes are based on our satiety index. You are less likely to overeat foods in green and are more likely to overeat those shown in red.

Recipes With a Higher Protein %

The chart below shows our six hundred NutriBooster recipes on a similar scale of protein % vs nutrient density. Again, you can dive into the detail in the interactive Tableuea chart here.

For some more inspiration, you can check out:

- Highest Satiety Index Meals and Recipes,

- High Satiety Index Foods: Which Ones Will Keep You Full with Fewer Calories?

You can also access our optimised food lists tailored to various goals here and learn more about our NutriBooster recipes here.

How to Identify the Right Balance of Protein vs Fat and Carbs for YOU

A key thing to note is that this is not a one-size-fits-all solution that will work for everyone. Additionally, most people don’t thrive if they jump from low to high-protein % extremes overnight.

Protein is a poor source of energy. So, your body will likely rebel, and you’ll end up in a rebound binge if you try to live on only chicken breast and egg whites for too long, especially if you’re used to a high-carb, high-fat standard western diet!

We find most people have the best long-term success when they progressively reduce carbs and (or) fat while prioritising protein and the other essential nutrients.

In our Macros Masterclass, we guide our Optimisers to first identify their current macro intake before nudging down their carbs and (or) fat until they normalise their blood sugars and begin losing weight at a sustainable rate. Once they reach their goal weight, later on, they can add back a little energy from fat or carbohydrates to maintain their weight.

While this process is simple in theory, it often takes some time and tracking for a few weeks. This will allow someone to identify new foods and meals they should introduce and the less-than-optimal foods and meals they may try reducing.

For more details, see:

- What Are Macros in Your Diet (and How to Manage Them)?

- Macronutrients [Macros Masterclass FAQ #2],

- Protein – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR),

- Fat – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR),

- Carbohydrates – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR), and

- Macros Masterclass.

The Basics of the Female Hormonal Cycle

We’ve already shown you the problem and the solution. If you want to learn a little more about the issues with nutrition that occur during menopause, read on.

Before we can talk about some of the physical differences someone can expect in menopause, it’s important to understand the physiological changes.

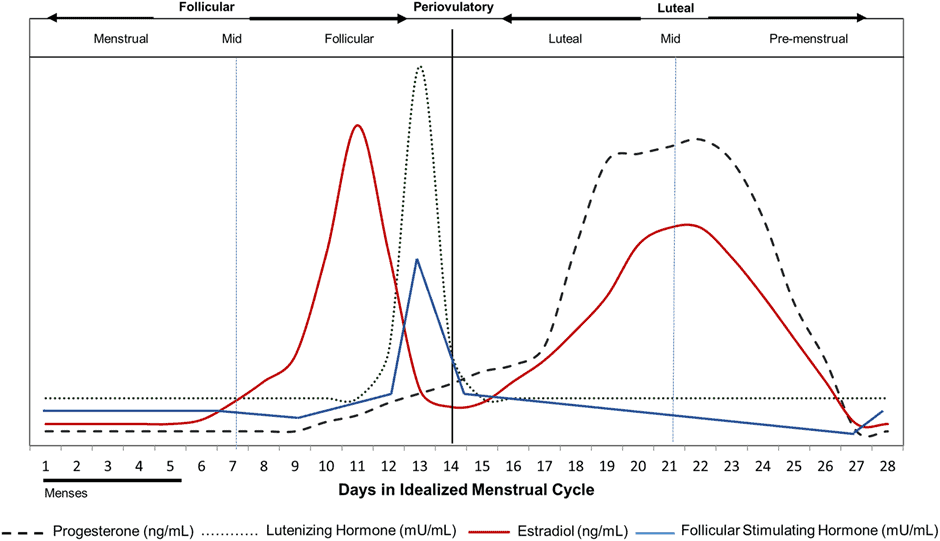

When a woman is fertile, her body releases various hormones—like estrogen, testosterone, and progesterone—cyclically, every 28 days (give or take seven days). This is known as her ‘menstrual cycle’.

Day 0 marks the first day of this cycle and what is known as menses (i.e., her period). Menstruation usually lasts 3-7 days. At this time, hormone levels are at their lowest.

From days 0 to 14, her estrogen levels slowly increase until they peak around mid-cycle. This middle day is known as ovulation, when the egg is released. This egg can develop into a baby if it’s fertilised.

From days 14 to 21, a woman’s progesterone slowly rises to its peak, and estrogen reaches its second high. However, if the egg released at ovulation is not fertilised, days 21 to 28 are marked by a fall in hormones.

This results in the body shedding its uterine lining that would have nurtured the egg into a foetus. The shedding of the uterine lining marks the beginning of menstruation and the start of the next cycle. This goes on for four or five decades until menopause begins.

What Changes Occur During Menopause?

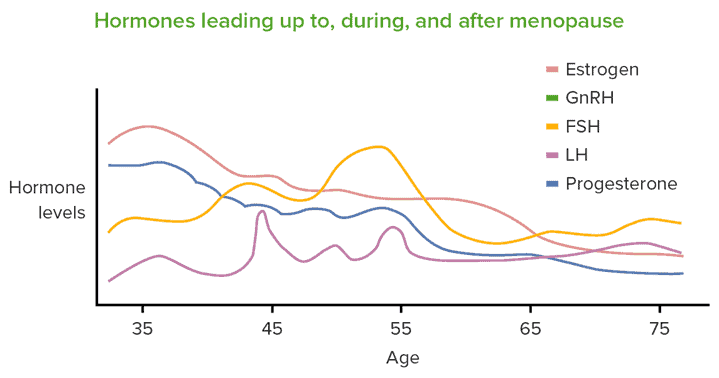

After a woman goes through menopause, these hormonal cycles wane and eventually cease. A woman no longer releases an egg that has the potential of being fertilised each month, and she no longer menstruates. As a result, her estrogen and progesterone levels fall tremendously, and her androgen levels increase relatively.

While not having to prepare for a 5–7-day bleed might sound exciting, it’s not all rainbows and butterflies. You see, estrogen, progesterone, and even testosterone are critical for a LOT of functions beyond fertility!

Estrogen is critical for cognition, building muscle, increasing and maintaining bone integrity, the health and rejuvenation of hair, skin, and nails, and keeping cholesterol in check. Progesterone plays a role in sleep regulation, thyroid function, estrogen regulation, and myelin formation. Together, the two drive your metabolism, fuel your sex drive, build bones, and keep you burning fat efficiently.

For more details on the female cycle and what to eat for each phase of your menstrual cycle during your fertile years, check out Blood Sugar, Insulin, and What to Eat for Each Phase of Your Menstrual Cycle.

What Is the Average Weight Gain During Menopause?

Weight gain and increased body fat are two main complaints of women in menopause. According to UW Medicine, women gain around 5-8% of their body weight in the two years after their final period. So, if you are about 130 lbs (59 kg), this can be as much as 10.5 lbs or 4.7 kg!

Why Am I Gaining Weight So Fast During Menopause?

During menopause, a woman’s estrogen and progesterone levels decrease. This, in turn, lowers their metabolic rate and increases anabolic resistance and insulin resistance.

Anabolic resistance and insulin resistance are two sides of the same coin. As we gain weight and lose muscle, we become insulin resistant. While it is often demonised, we require insulin to build muscle and limit gluconeogenesis (i.e., the conversion of dietary protein to glucose rather than muscle). Somewhat counterintuitively, the solution to reducing gluconeogenesis is not to reduce your protein intake but rather to prioritise protein while reducing excess energy from fat and/or non-fibre carbs.

For more details, see What Is Insulin Resistance (and How to Reverse It)?

The figure below shows how hormones change before, during, and after menopause. Note the long slow decline of estrogen and progesterone.

As a result of these hormonal changes, women lose lean mass (i.e., muscle) as they age. Additionally, activity levels often also decrease, meaning we require less food. Appetite often lowers to compensate for the reduced activity levels and muscle mass. Still, most people continue to eat as they usually would before menopause because we are creatures of habit. As time goes on, this leads to an increase in body fat and a loss of muscle.

Andropause in Men

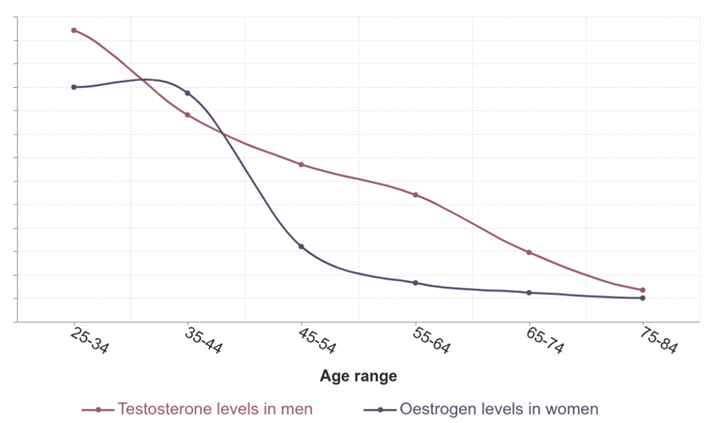

While menopause in women sometimes gets more attention because of a more sudden cessation of the menstrual period, men also experience similar changes. This is sometimes called ‘andropause’, as androgenic hormones like testosterone decrease with age.

As we can see in the chart below, testosterone declines steadily in men, while there is a more sudden drop in estrogen around the menopausal years. This typically leads to a similar loss of muscle and an increase in belly fat in men.

High-stress levels raise cortisol which increases the conversion of testosterone to estrogen in men, leading them to be more feminine. While good sleep, stress management and exercise can help mitigate this decline, getting adequate protein within our reduced energy budget is critical for both men and women.

Extended Fasting and Aggressive Dieting

To address this weight gain, many turn to intermittent and long-term fasting, extreme calorie restriction, intense cardio, and other aggressive strategies to improve their body composition.

While simply eating less to lose weight might sound easy, these approaches might exacerbate the problem. This is because extreme calorie deficits, especially without an adequate focus on protein, push the body to catabolise its lean muscle mass for energy. Over time, this results in accelerated lean mass loss.

Your lean mass refers to your organs, bones, and muscles. These tissues are metabolically active, meaning they burn calories at rest (and maybe even more if you’re physically active). When you lose this lean mass, the body’s metabolic rate also decreases, and the rate you burn calories may suffer even further. Hence, if you begin losing muscle, you start losing tissues that stoke your metabolic fire.

Raubenheimer and Simpson highlight that a woman’s appetite increases in response to the loss of lean mass to obtain more protein. Sadly, most fasting or dieting strategies focus on eating less food less often or limiting one macronutrient (e.g., carbs, fat, or even protein).

Is Fasting Good for Someone in Menopause?

As we explained earlier, fasting too much or for too long can push someone’s body to start eating away at their lean body mass. As a result, weight gain may compound, resulting in a loss of lean body mass, a slowing metabolism, and increased body fat.

If you remember from the Protein Leverage Hypothesis, someone will continue to eat more energy (i.e., calories) until they satisfy their bodies’ protein demands. However, it can have disastrous consequences in menopause. When we allow ourselves to eat again after extended fasting or aggressive calorie deprivation, our appetite kicks in to ensure we can rebuild our fat stores quickly.

Slowed metabolic rate, lower activity levels, and decreased muscle mass combined with extended fasting or limiting calories can lead to an increased appetite for poorly-satiating, nutrient-poor, low-protein % foods.

Because it’s much more challenging to build muscle as we age, we mustn’t subject ourselves to aggressive strategies that lead to muscle loss that is much harder to build back. This interview with Don Layman is an excellent deep dive into the importance of regular protein feeding.

In our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, we use blood glucose as a fuel gauge to ensure there is an overall energy deficit while encouraging people to prioritise high protein % foods and meals, particularly when they are hungry, and their blood glucose indicates they still have plenty of fuel on board.

What Is the Best Form of Exercise to Mitigate Menopausal Weight Gain?

In addition to changing what we eat, increasing our activity output is helpful. However, not all physical activity is created equal.

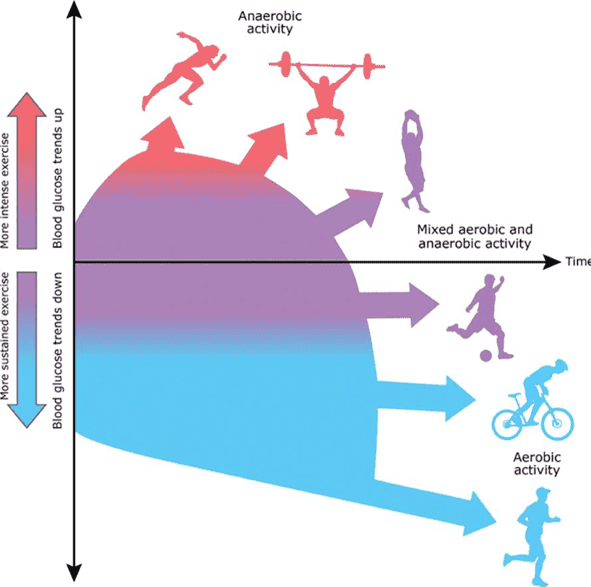

For example, excessive cardio—or running, biking, swimming, hiking, and even walking—can increase the rate at which you burn lean mass, especially if you aren’t engaging in much or any exercise that builds muscle. Hence, strength and resistance training (i.e., weight training) is often best, especially when combined with lower-intensity activities.

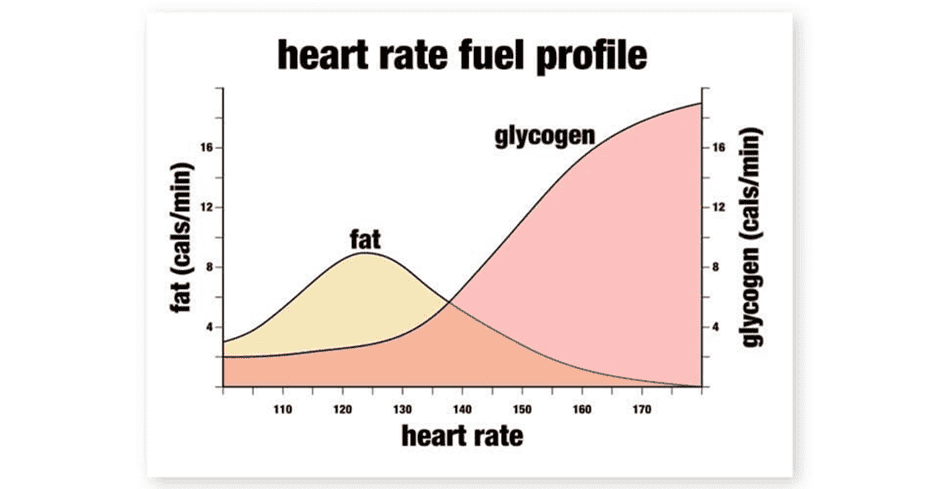

The figure below shows how we use fat vs glycogen. Lower-intensity exercise like walking or cycling tends to use more fat, whereas high-intensity activity that increases your heart rate tends to use more glycogen. Glycogen is a form of glucose stored in your liver and muscles.

Gentle exercise that maintains a lower heart rate where you can still breathe easily—commonly referred to as zone 2 or low-impact steady state (LISS)—can improve your fat burning and fitness. A good example is walking on a gentle incline.

Not only can you do this style of exercise every day without becoming sore or exhausted, but it also tends to lower your glucose gently without provoking excessive hunger. If you’re ‘chasing your trigger’ in a Data-Driven Fasting Challenge, you’ll find your blood glucose lowers nicely, and you can refuel with a robust meal.

In contrast, high-intensity cardio exercises like running, intense cycling, heavy hiking, and swimming can burn many calories and elevate your heart rate. However, they also tend to elicit a stress response in the body.

This can release stress hormones and the catabolic hormone glucagon, which signal the body to begin breaking stored energy down NOW, regardless of whether it comes from your fat or muscle. When this occurs, it can temporarily boost your blood glucose.

While higher-intensity anaerobic activity now and then has some profound health benefits, it can be accompanied by cravings and hunger because of the glucose crash and intense hunger that often ensues when it’s over. Hence, it’s wise to plan to eat shortly after the activity before your glucose bottoms out, and you feel ravenous and go to the pantry for any nutrient-poor, energy-dense food you can wrap your hands around.

In addition to moderating your high-intensity anaerobic activity, you want to avoid training between these extremes. These activities could be considered ‘extended cardio’ and tend to require a blend of fat and glucose. As a result, you may experience more intense hunger afterwards. If you’re insulin resistant and undereating protein, your body is more likely to draw on your muscle in this instance to create glucose via increased gluconeogenesis.

Why Does Bone Density Decrease in Menopause?

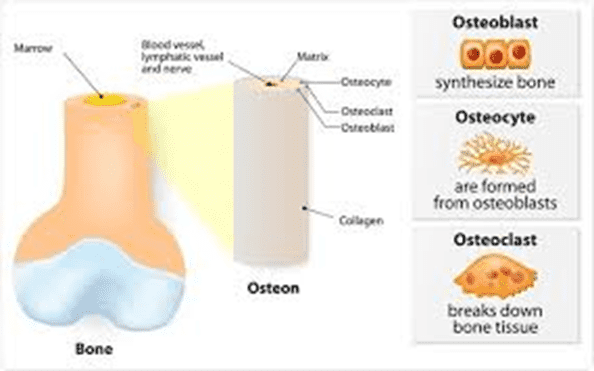

In addition to losing muscle mass, it is also not uncommon for women to lose bone density or bone mass (i.e., osteoporosis or osteopenia, respectively) during menopause.

Bone is not a stationary tissue; it is constantly being broken down to use its mineral stores and reabsorbed. This is known as bone reformation or bone remodelling. Nonetheless, the body uses its bone reserves to supply its mineral needs in the absence of certain nutrients in our diet, which we’ll discuss below.

The two main types of bone cells active in the bone remodelling process are osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Osteoblasts are responsible for building bone mass, whereas osteoclasts are responsible for breaking down and recycling bone. It’s easy to remember osteoBlasts as the cells that build and osteoClasts as the cells that kill.

Most women have heard menopause can be a scary time for bone density and bone mass because it tends to decrease. We can attribute this to falling estrogen levels and relative increases in androgens and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG). Estrogen stimulates osteoblasts, whereas androgens stimulate osteoclasts. Hence, it becomes difficult to maintain—let alone build—bone as we age.

When the food we eat is packed with vitamins, minerals, and protein during our menstruating years, our bodies have the resources to build our bones up and put these nutrients away for a rainy day, like a savings account.

As time goes on and our diet is not as nutritious, we need minerals we are not getting from our diet, or our bodies need to stabilise our blood pH. So, it will begin to release these minerals from our bones to regain homeostasis (i.e., equilibrium).

How Can I Improve Bone Density Before Menopause?

As mentioned above, several factors influence someone’s bone density as they enter menopause. Subsequently, we can do a few things to prepare for menopause before it occurs and maintain our bone density as we enter it.

Consuming adequate protein is critical for building and maintaining bone density. Studies have shown that dietary protein can increase calcium absorption, decrease osteoclastic activity, increase growth hormone levels, and improve muscle mass. Increased muscle mass can increase bone mineral density via bone loading.

In addition to getting adequate protein, it is also critical to prioritise nutrient density so we can get sufficient quantities of bone-supportive nutrients. While most people think that vitamin D and calcium are the only vital nutrients for our skeleton, it’s really much more than that! To build and maintain healthy bones, we need:

- Calcium. Calcium is perhaps the most well-known component of bone, with nearly 98% of our skeletal system consisting of this mineral. This makes calcium the most abundant inorganic mineral in the body. Keep in mind calcium makes up your teeth, too!

- Copper. Low serum copper levels have been associated with decreased bone mineral density. Copper is critical for synthesising and catalysing enzymes that help incorporate collagen and elastin into the bone matrix.

- Magnesium. Magnesium is not only a synergist of calcium, but it is also a critical cofactor for calcium absorption, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D utilisation. Hence, those deficient in magnesium tend to have difficulties absorbing and using calcium (and vice versa). Studies have shown that low magnesium levels are associated with altered bone stiffness, slowed cartilage and bone differentiation, and matrix calcification. In mice, it has been linked to reduced osteoblastic output.

- Manganese. While our knowledge of manganese is somewhat limited compared to other nutrients, studies have shown that manganese is critical for bone and teeth mineralisation and formation.

- Phosphorus. Like magnesium, phosphorus is a synergist, antagonist, and cofactor for calcium absorption, and around 15% of the body’s phosphorus stores are found in the bones. However, too much phosphorus in proportion to calcium can result in accelerated bone density loss. Because phosphorus is a calcium antagonist, too much can push the body to release calcium from bones and teeth to balance blood pH. You can check out our article on nutrient balance ratios for more!

- Potassium. As with magnesium and phosphorus, potassium is another synergist, antagonist, and cofactor for calcium absorption. Studies have shown that increased potassium intake was associated with a significant decrease in risk for osteoporosis. Considering 97% of Americans are deficient in this nutrient, it’s puzzling whether its absence from the diet has contributed to our low bone density epidemic.

- Zinc. Our bodies require zinc for normal skeletal growth and bone homeostasis. However, researchers don’t necessarily know the mechanisms of action. Zinc and copper are involved in many reactions related to collagen and elastin synthesis, which could be how they contribute.

- Vitamin C. Scurvy, the disease associated with vitamin C deficiency, results in alterations in bone matrix and structural collagen formation and increased osteoclastic activity. Alongside copper and zinc, vitamin C is critical for collagen and elastin formation. Hence, deficiency is directly associated with osteopenia and certain types of osteoporosis.

- Vitamin D. Vitamin D is critical for calcium absorption and utilisation in the digestive tract. This nutrient—which we make when exposed to adequate sunlight—stimulates the hormone calcitonin, which increases calcium uptake in the digestive system, and inhibits parathyroid hormone (PTH). PTH stimulates osteoclastic activity and bone resorption.

- Vitamin K2. Although most people attribute bone integrity to vitamin D, it would be nothing without vitamin K2. Vitamin D increases calcium uptake, yes. But we need adequate vitamin K2 to regulate calcium storage and mineralisation of the extracellular matrix, so it ends up in our bones and not our arteries, tendons, or ligaments.

How Can I Prevent Bone Density Loss in Menopause?

Bone mineral density steadily increases from when a woman begins menstruating in her early teens into her twenties and peaks in her early thirties.

But when she enters menopause, bone mineral density tends to decline without intentional intervention.

Nutrition

While protein is essential for reasons of its own, many high-protein foods like meat, poultry, fish, and dairy products contain considerable amounts of this entire nutrient profile. Hence, consuming more high-protein animal foods gives you the amino acids that make up protein and supplies you with the vitamins and minerals necessary to build bone and regulate the process.

If you’re interested in fine-tuning the micronutrient density of your diet, you may enjoy our four-week Micros Masterclass. Here, we walk our Optimisers through perfecting their nutrient intake with whole foods.

Exercise

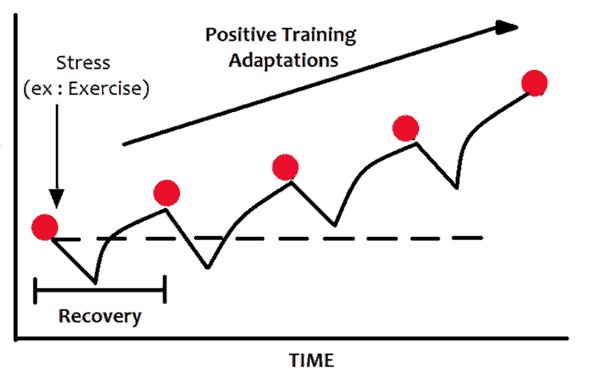

In addition to diet, exercise is another tool we can use to improve bone mineral density and mass. However, as we mentioned above, regular old cardio is not what we’re talking about!

If you’re familiar with the mechanisms of action behind weight training, it works by slightly tearing the muscle. As your body repairs and heals it, new muscle fibres grow back in place, which results in increased strength over time.

Interestingly, your bones are similar when it comes to weight training. Studies have shown that the tension exerted on your bones during weight training has a strengthening effect, and long-term weight training has repeatedly shown that it helps slow bone loss and build bone mass.

Weight training is critical to combat the muscle loss that comes with aging and menopause. But it must be done with a weight that is challenging enough to stimulate growth. Weight training is not the 3-8 pound dumbells left over from the Jane Fonda VHS tapes from the eighties.

While it’s good to start with a light and manageable weight that won’t break you, progressive overload is critical. Once you can do multiple sets for 4 – 10 reps, increase the weight a little to make it more challenging. You might be surprised at where you end up after a few months of consistent training.

For more details on exercise, see Optimising Your Exercise [Macros Masterclass FAQ #7].

Mood Changes During Menopause

In addition to weight gain, hot flashes, muscle loss, and decreased bone mass, some of the most reported symptoms of menopause include mood and sleep changes.

Hormones influence the synthesis and breakdown of neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin, melatonin, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. Deficiencies or fluctuations in one or all of these neurotransmitters are directly associated with conditions like anxiety, depression, mood swings, insomnia, hypersomnia, or a combination of these conditions.

Although the fall of your hormones largely contributes to some of these changes, the body synthesises all these neurotransmitters using vitamins, minerals, and amino acids. Therefore, if you are not consuming enough of these nutrients from your diet, you are more likely to experience adverse symptoms.

The following nutrients are essential for neurotransmitter synthesis—and, in turn, mental and emotional health:

- Tryptophan. Tryptophan is an amino acid found readily in animal foods like meat, poultry, and dairy. It is a precursor for the feel-good, calming neurotransmitter serotonin and the sleep-dependent neurotransmitter melatonin.

- Phenylalanine and Tyrosine. Phenylalanine and tyrosine are precursors to the happy and energising neurotransmitter dopamine. We need adequate amounts of these nutrients to produce norepinephrine. Low levels of norepinephrine have been associated with attention deficit disorders, depression, and poor energy.

- The B Vitamin Family (B1, B2, B3, B6, B9, and B12). The B vitamin family is responsible for converting precursor nutrients into usable substances, like whole neurotransmitters (i.e., dopamine or serotonin).

- Vitamin C. Like the B vitamin family, vitamin C is also critical for synthesising enzymes that turn precursor nutrients into neurotransmitters.

- Copper. Copper is especially critical for breaking dopamine down into norepinephrine.

- Iron. We require iron for turning amino acids into intermediate substrates that turn into neurotransmitters.

- Magnesium. Magnesium is critical for catalysing the conversion of tryptophan into serotonin and, eventually, melatonin. It is also essential for the production of GABA, the calming neurotransmitter.

- Zinc. Zinc is critical for the synthesis of serotonin and melatonin.

How Do I Prevent or Avoid the Psychological Changes of Menopause?

Preventing the adverse changes associated with mood that often accompany menopause is not too different from avoiding changes in bone density or metabolism. What you put on your plate and shovel into your mouth goes a long way!

Prioritising nutritious higher-protein foods over nutrient-poor processed ones and optimising your nutrient density by focusing on nutrient-dense whole foods and nutritious recipes is the best way to avoid some of these commonly-reported menopause symptoms.

By giving your body the precursors it needs to synthesise feel-good and pro-sleep neurotransmitters, you at least have the raw ingredients for a healthy mood.

Where Do I Start?

- While most people benefit from more protein, calcium, or potassium, you may already be getting plenty. Hence, your needs for that nutrient will be lower, and you might do better if you direct your appetite towards other nutrients you might be falling short of.

- You can take our free 7-day Nutrient Clarity Challenge to determine those nutrients. Here, you will record your food in Cronometer for seven days. In the end, we will give you a free nutrient fingerprint chart to show all the nutrients you’re getting—and not getting—and some foods and recipes that could help you fill those gaps.

- In addition to our Nutrient Clarity Challenge, we’ve designed our suite of nutrient-dense food lists and NutriBooster recipes to make it as easy as possible for you to start your Nutritional Optimisation journey.

- We’ve also put together our nutrient-dense food lists that are optimised and tailored towards your goals and preferences. These are the most nutrient-dense foods and recipes out there, so you won’t have to try that hard to get all your essential vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, and amino acids!

- Aside from our food lists and recipes, we have our four-week Macros Masterclass, which will walk you through dialling up your protein and fibre and back your fat and carbs to match your goals and preferences.

- If you already feel confident in your protein intake, you might enjoy our Micros Masterclass, which focuses on filling in the gaps in your micronutrient intake. While protein is the foundation of a good diet, micronutrients are the icing on the cake!

- Lastly, we also have our four-week Data-Driven Fasting Challenge. Here, you will learn to use your glucose meter as a fuel gauge to determine when to eat and what to refuel with.

Summary

- Menopause is the cessation of menstruation and fertility in women, which usually sets in between ages 45 and 60.

- During perimenopause and into menopause, women may experience weight gain, decreased bone density, and mood changes.

- These changes tend to occur because hormones like estrogen and progesterone are not produced to the degree they were in their childbearing years. As a result, the amount of androgens and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) also increases.

- To prevent and protect against these ever-dreaded symptoms associated with menopause, it’s critical to prioritise animal protein and other nutrient-dense foods to give your body the raw ingredients it needs to build bone, muscle, and other bodily substances.

- Additionally, weight training is vital for building muscle and strong bones.

Found this today: https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/966718

It deals with meal timing, and eating later vs. earlier in the day. I posted this because I have a feeling this might help explain the “early bird special” phenomenon with older people. I’ve noticed myself that the older I get, the earlier I go to bed and wake up, which means that I eat earlier as a result (I’ve become an early bird). If I don’t eat “dinner” at about 2 or 3 in the afternoon, I get real sleepy right at about 3:30, and then end up dragging myself through until about 7 at night. I’ve tried caffeine, various energy-creating supplements (other than energy drinks–things like AKG, phenylalanine, and tyrosine), protein powders, and even trying to nap at around noon (often ineffective), but simply eating my evening meal is the most effective. An afternoon nap (when I can actually get to sleep) comes in second. I’m entertaining the notion that my hunger is so well trained (after years of keto), that this may be the only way my body has of telling me that I need to eat. My weight is stable at 160 lbs. after twice bouncing the scale from weight gain to weight loss. I remain high-protein and low-carb.

I’m trying to avoid the use of any kind of prescription sleeping pills for fear I could become dependent on them. Melatonin only serves to make my eyelids heavy–does nothing to turn off the brain (I’m still conscious). Same for tryptophan, serotonin, and carbs before bed. Benadryl works well, but long-term use of it encourages Alzheimer’s.

What is it about age 60 that seems to turn the clock on its side (assuming a round clock face)? My circadian rhythm seems to have gone out the window…either that, or maybe it’s preparing for a seasonal change. This has never happened to me before this year.

If I give in to the “afternoon sleepies”, then I’m awake again at 10 or 11 P.M., and up all night. I find that dinner in the afternoon keeps me awake until about 7 P.M., and then I just go to bed and wake up at about 4 or 5 A.M.–that’s a schedule I can live with.

Same boat here as a trucking company wife. Early to bed and 3-4 am to rise. I find sticking this works best for me. When I try to alter it, it does not work well. Also can not take melitonin, tryptophan, serotonin, and carbs before bed, so decide to try CBD oil or gummies from Nuleaf and it has been a game changer in giving me that deep restoritive sleep I was looking for without the side effects I was getting from suppliments. Focusing on higher protein, lowering fat & carbs within my caloric deficit and I now feel my best!

Hey there,

Have you investigated whether or not you’re eating enough (quantity) or frequently enough? The timeframe you’re describing fatigue and wakefulness suggests you may have a cortisol dysregulation, which could be throwing off your circadian. There’s a lot that could be throwing this off, but just some food for thought 🙂