It’s no wonder that so many people believe:

- ‘insulin is the enemy’, and

- ‘carbs make you fat’.

I recently attended and spoke at a low-carb conference with my son. After listening to many speakers over the two days, my 16-year-old son Mike asked,

‘why does everyone here believe insulin is evil?’

In December 2021, Mike was diagnosed with type 1. If he did not have exogenous insulin, he would likely be dead.

A few weeks after the conference, he set a new Australian under-18 deadlift record of 231kg (509 lbs). Before he was diagnosed with Type 1 and started on insulin, his maximum deadlift was 160 kg.

Not only has he become stronger with insulin, which has allowed him to rebuild his muscle mass, but he is also lean, athletic and thriving today because of insulin.

In fact, without insulin, he probably wouldn’t have ever been born because his mum, who also has T1D, would have been dead long before I met her.

So—at least for our family—insulin is not the enemy; it’s just the life-saving stuff sitting in vials in our fridge that is critical for half of my family members’ survival.

I feel fortunate that living with two people who have Type-1 Diabetes has given me some insights. In this article, I want to share some of my experience and insights to show you:

- Why this overly simplistic ‘insulin is evil’ belief works… until it doesn’t; and

- A more complete understanding of what’s happening in your body to empower you to pull the right levers at the right time to get the desired results.

- Why Simple is Sometimes Best

- Why Low-Carb Works: It’s Not Why You Think

- Why Modern Food Is Making Us Fatter

- Why ‘Eating Fat to Satiety’ Is Bad Advice

- Why Many Believe the Carb-Insulin Hypothesis

- Dietary Fat Requires Insulin Over the Longer Term

- How Insulin Really Works

- Basal vs Bolus Insulin

- A Lower-Carb Diet Can Help Reduce Insulin

- A High-Fat Diet Can Worsen Insulin Resistance

- How To Lower Your Insulin and Lose Weight

- Why Your Premeal Glucose is the Most Important Thing You Can Manage

- How to Lower Your Premeal Glucose and Hence Your Insulin

- What’s Your Glucose Trigger?

- Summary

- More

Why Simple is Sometimes Best

Before we dig into how insulin works in your body, I want to ‘steelman’ my argument by showing why a lower-carb diet works for so many people.

The presentation at the conference that got me thinking and inspired this article was once from a surgeon who gives simple and effective low-carb advice for rapid weight loss for morbidly obese patients before surgery.

To be clear, he’s doing great work and getting rapid results for people who desperately need it. But step 1 of 5 was: “Insulin is the enemy, and carbs put your insulin up.”

After this presentation, a good friend sitting next to me, who knows my thoughts on the common misconceptions about insulin resistance, said “I bet this stuff makes you angry”.

He then said, “It is easier for the world to accept a simple lie than a complex truth.”

To be fair, I don’t think it’s a ‘lie’ but a half-truth that can be helpful, especially if time is limited to get quick results. But, as you will see, this logic isn’t exactly what many think is happening.

By the time people come to our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges and Macros Masterclass, many participants have tried low carb, keto, carnivore, and a wide range of fasting hacks like 16:8, 20:4, OMAD, ADF and extended fasting.

While these people have achieved solid initial results, they often stall out and find they gain the weight back when they merely focus on reducing carbs, believing they are the sole cause of insulin resistance.

Once they understand that dietary fat can also contribute to fat gain and increased insulin resistance, they can restart their weight loss.

Why Low-Carb Works: It’s Not Why You Think

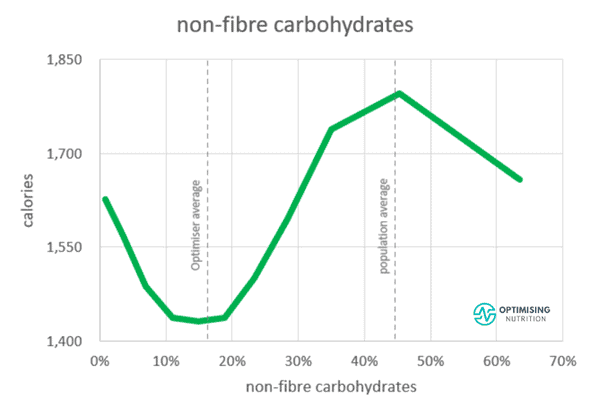

The chart below shows the average satiety response to carbohydrates from our analysis of one hundred and fifty thousand days of data from forty-five thousand Optimisers. Notice how the vertical line towards the right shows how the population’s average carbohydrate intake (45% non-fibre carbs) coincides with the maximum calorie intake.

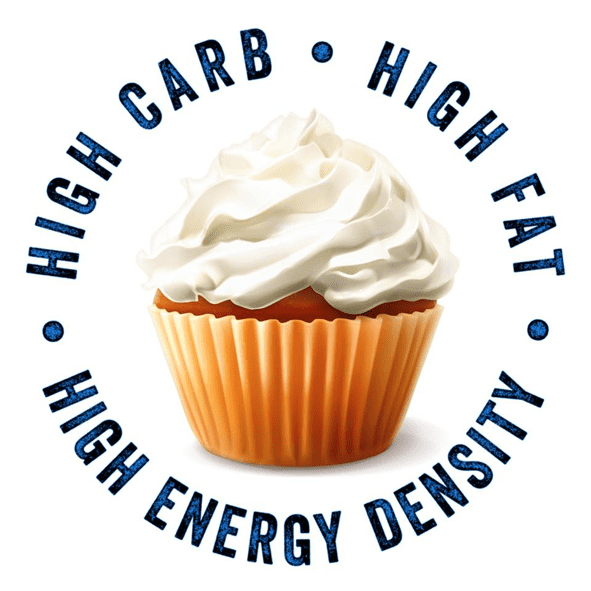

A low-protein blend of fat and carbs is the basic formula for modern, ultra-processed, hyper-palatable junk food. These are the foods we have no off switch for.

Per our work on the Protein Leverage Hypothesis, we know that lowering the overall percentage of total calories from protein allows us to eat more.

What most people view as ‘bad carbs’ are actually this fat-and-carb combo. These foods simultaneously fill our fat and glucose fuel tanks and elicit a supra-additive dopamine response, so we want more of them.

Towards the left of the carb satiety chart shown above, we see that reducing non-fibre carbohydrates to 10-20% aligns with a 23% reduction in calories! This is why a carb-restricted diet is so magical;

reducing carbs eliminates ultra-processed foods that combine carbs and fat, which improves satiety and results in that ‘effortless weight loss’ everyone speaks about.

Additionally, people who move away from ultra-processed fat-and-carb combo foods often eat more protein—which is the most satiating.

As we can see in the chart below, foods with a higher protein %, or a higher percentage of total calories from protein (i.e., less energy from fat and carbs), provide the greatest satiety per calorie.

Why Modern Food Is Making Us Fatter

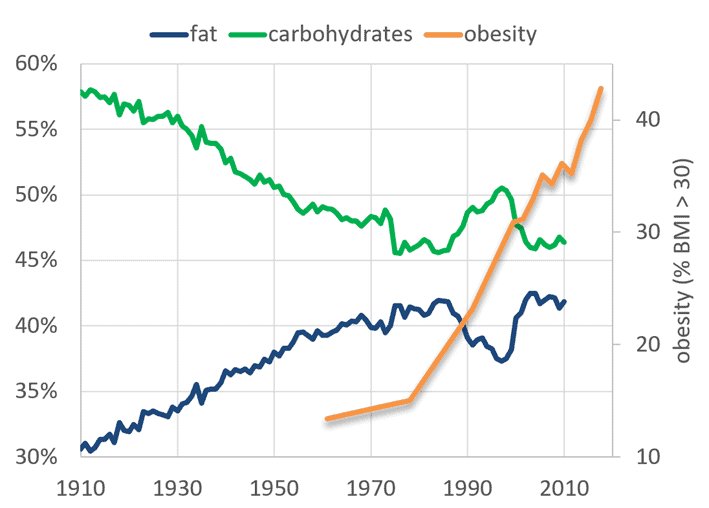

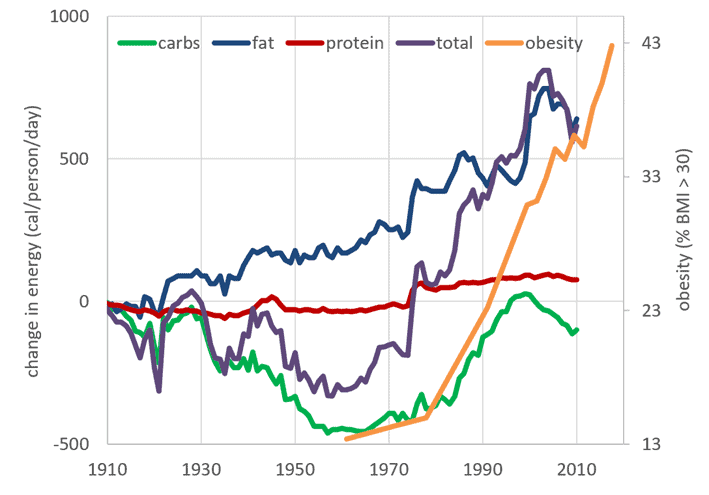

The following chart was created using data from the USDA Economic Research Service and Centres for Disease Control. Here, we can see how the American food system has changed over the past century. Unfortunately, the global food system has also followed the lead of the US.

As our food system has trended towards a magical blend of carbs and fat, obesity has taken off. This lethal combo is addictively delicious and poorly satiating, keeping your appetite in overdrive.

By increasing how much we process our food, food manufacturers have been able to manufacture longer-lasting, more stable, and more affordable forms of sustenance. However, it has also given them the tools to create more ‘food’ we love to eat and buy more of.

Modern processed foods are made from ultra-cheap, subsidised ingredients like refined grains, added sugar, and industrial seed oils with minimal nutritional value. While these ingredients would taste awful on their own, mixing them and adding flavourings gives us the magical fat-and-carb combo that is highly addictive.

When we zoom out and look at long-term nutrition trends, we see that our carb intake has dropped and returned to levels similar to what they were a century ago. On the other hand, our fat intake has increased by around seven hundred calories per day, mostly from industrial seed oils.

Since the 1960s, our consumption of both carbs and fat has also increased. This has allowed many to point at carbs as the culprit for our ongoing obesity epidemic.

Because carbohydrates raise insulin the most in the short term and insulin is known as the anabolic fat storage hormone, it sort of makes sense that many would blame obesity on carbs and insulin, similar to how we do in the carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity.

However, if there is one smoking gun, I would say it is the 700 extra calories per person per day from processed, nutrient-poor, refined fats!

Why ‘Eating Fat to Satiety’ Is Bad Advice

Building on the belief that carbs are bad because they spike insulin the most, many believe that fat is a free food because it doesn’t spike insulin or blood glucose. However, the effects aren’t so simple once we take a closer look.

Back in the keto heydays, I believed I could ‘eat fat to satiety’. I’m sad to admit that I even thought that my body fat would melt away if I could raise my ketones by eating more fat and fewer carbs and protein.

Theoretically, this would put me in a situation similar to someone with uncontrolled Type-1 Diabetes. But, unfortunately, it didn’t work out that way, and I just got fat and puffy.

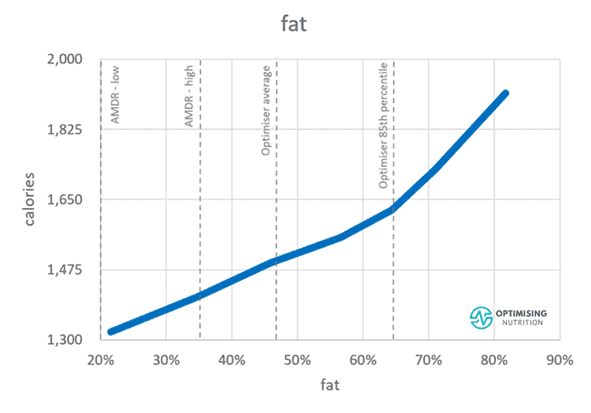

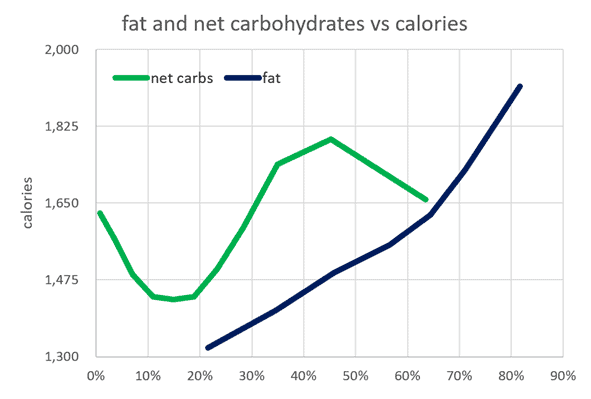

But when we look at the satiety response to fat, we see that fat contains very few micronutrients (i.e., vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and essential fatty acids), which makes it the least satiating macronutrient.

At nine calories per gram, it is also the most energy-dense. So fat is easy to overeat and can quickly lead to fat gain if we believe it’s virtually a free food because it doesn’t spike insulin.

Moving from a high to low-fat intake aligns with a 37% calorie reduction. Looking back now, the ‘just eat fat to satiety’ advice I got from many of the keto gurus seems to be pretty dumb advice.

The same could be said for the other input I received, like ‘avoid protein because it turns to glucose in your bloodstream and increases your insulin!’

When we compare fat and non-fibre carbs, we see that reducing fat has a much more significant impact on our energy intake than lowering our carb intake.

If your glucose levels increase after eating more than 1.6 mmol/L (30 mg/dL), it’s wise to reduce carbs.

But the reality is that decreasing your intake of carbs, fat, or carbs AND fat will increase satiety as long as you prioritise protein and the other nutrients that our analysis has shown are critical for satiety.

Why Many Believe the Carb-Insulin Hypothesis

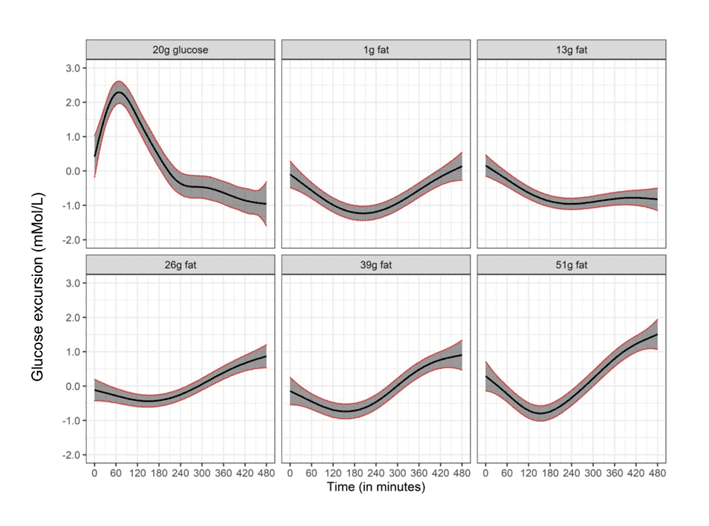

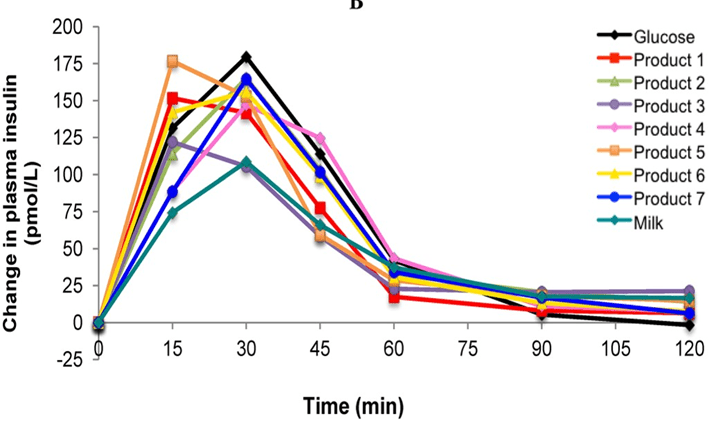

I think the part of the misunderstanding around insulin comes from how we measure our insulin response to food. To explain, the chart below shows testing from the food insulin index investigations. At first glance, we see that:

- High-carb foods like pure glucose that are shown in black raise insulin the most over the short term, while

- High-fat, lower-carb foods like milk, represented by the aqua line, raise insulin less over the long term and tend to keep it just a bit above baseline.

This understanding benefits people with diabetes trying to bring sugars back into the healthy range and remove significant variations. Shifting your primary fuel source from carbs to fat can help you get off this blood sugar-insulin rollercoaster.

However, it’s important to note that:

- The insulin index testing data only looks at the first three hours after eating;

- Higher-fat foods still generate an insulin response at the three-hour mark and beyond; and

- The measurements we have are only the changes in insulin over baseline.

So, these tests only provide limited insight into how insulin works. No wonder there has been so much misunderstanding and confusion about it!

Dietary Fat Requires Insulin Over the Longer Term

Unfortunately, it’s hard to accurately test someone’s insulin response to a food if they have a functioning pancreas. However, we can observe the people who need to inject all their insulin manually to learn how each macronutrient affects blood sugars over the short and long term.

A recent study of people with Type-1 Diabetes showed that when insulin wasn’t taken:

- Dietary glucose raised blood sugar in the first three hours or so;

- However, dietary fat initially lowered blood glucose in the short term but caused a significant rise in the three to eight hours after the meal.

- When combined, blood glucose increases and stays elevated and away from baseline.

This aligns with what we find in people in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, where people use their premeal glucose to guide when and what to eat. Carbs raise glucose in the short term. However, dietary fat keeps their blood glucose from returning to baseline over the longer term.

People with Type 1 Diabetes on a lower carb diet also understand that they need insulin over the long term for higher fat meals.

To ‘hack’ your premeal glucose and get it to return below trigger sooner, you need to dial back your dietary carbs AND fat in relation to protein, similar to how we do in our Macros Masterclass.

Rather than simply reducing the peak in glucose after you eat, it’s much more helpful to manage the area under the curve. This is a function of both carbohydrates AND fat.

To draw down on your stored energy and reverse insulin resistance, you must lower your blood glucose bit below your normal before you eat.

How Insulin Really Works

Testing the insulin response to food in healthy subjects is fraught with inaccuracy and just leads to confusion and mistaken beliefs about insulin.

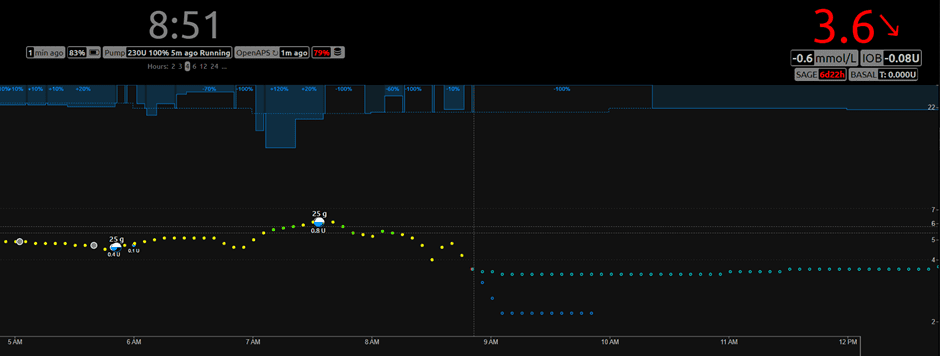

However, we can get a much clearer picture of how insulin works by looking at a closed-loop artificial pancreas system that’s working to keep glucose for someone with T1D in the healthy range.

For example, the image below shows the Nightscout dashboard for my wife Monica’s system that I can monitor at any time. Yellow dots represent the continuous glucose monitor (CGM) signal on the bottom. The thick blue bar on the top is her basal insulin.

Every five minutes, the closed-loop artificial pancreas system adjusts her basal insulin to stabilise her blood sugars into the normal healthy range.

- When her glucose starts to drift up, the algorithm releases a bit more insulin.

- When her blood glucose drops, it reduces the basal insulin to allow the body to release glucose from storage.

It’s a beautiful system that does a fantastic job of mimicking how a healthy pancreas functions!

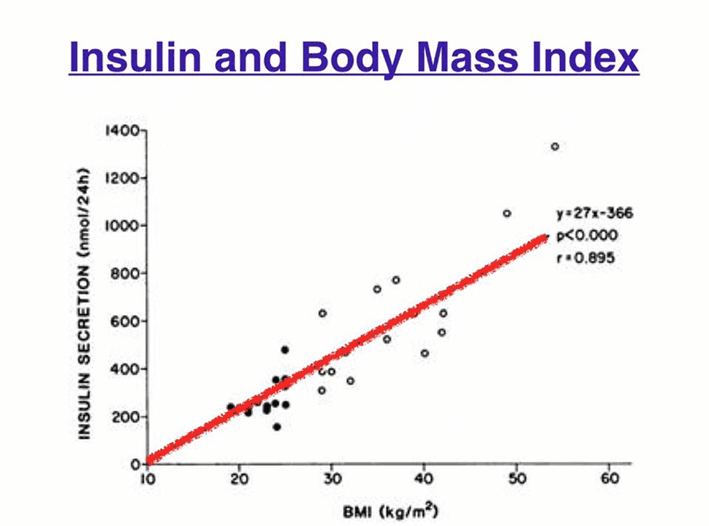

Moni also doses insulin around her meals (i.e., bolus insulin). However, the big takeaway from all this for me is that her bolus insulin only makes up a small fraction of her total daily insulin dose.

Only 18% of her total daily dose is related to food. She requires the rest of her daily insulin to stop her body from disintegrating! This basal:bolus split is typical for people who eat lower-carb and have their sugars under control.

Over recent years I’ve seen many people become obsessed with achieving flatline blood glucose using on their CGM. But they’re managing the minutia!

Trying to manage your insulin based on the blips of your CGM is like trying to measure the volume of the ocean by measuring the height of the waves standing on the beach.

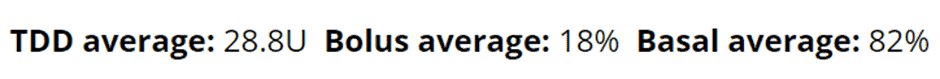

If you want to reduce your insulin, you need to understand that your insulin requirements increase the bigger you are, as you will need to hold all your stored energy in storage!

Basal vs Bolus Insulin

One of the most critical things for managing Type-1 is getting your basal insulin right.

For those of you who are new to basal and bolus insulin dosing, the image below simplistically depicts:

- basal insulin (i.e., insulin required all the time in the background), vs

- bolus insulin (i.e., the insulin needed around meals).

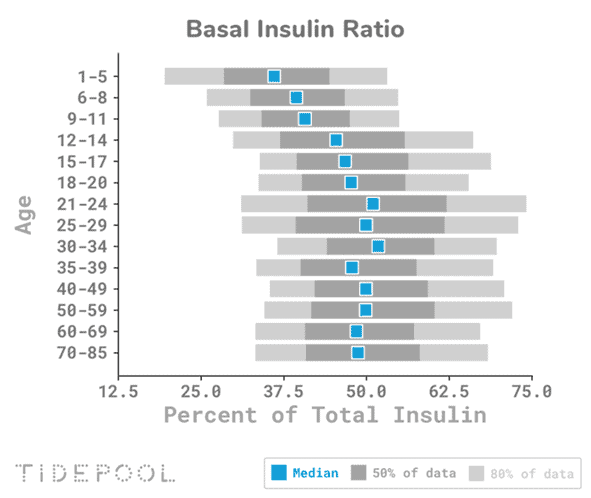

The chart below from Tidepool’s analysis of insulin pump data shows that the typical basal:bolus ratio for someone on a standard western diet is around 50:50. However, this can be as high as 90:10 for people with Type-1 Diabetes on a high-fat keto diet (i.e., where someone is purposely eating a lot of fat).

Remember, consuming fat keeps your sugars from returning to baseline longer and keeps them higher. Hence, higher fat might not be the best option.

A Lower-Carb Diet Can Help Reduce Insulin

We’ve found that opting for a lower-carb diet has been the most helpful for T1D management. But it’s important to note that high-fat and low-carb are different.

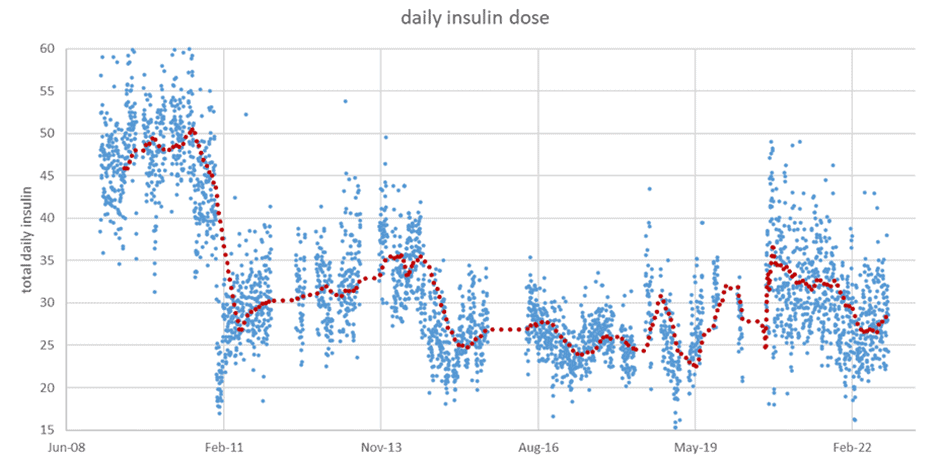

The chart below shows Moni’s total daily dose over the last ten years. Moni’s insulin requirements effectively halved when we switched to a lower-carb, paleo-style diet in 2010 focused on meat, fish, and vegetables.

I believe this reduction in total insulin requirements is due to several factors, including:

- Dietary fat requires less insulin to metabolise and store in comparison to carbohydrates.

- Getting off the blood sugar-insulin rollercoaster enables someone like my wife to stop eating out of lows from inaccurate insulin dosing.

- Protein is the most satiating macronutrient, and high-protein foods contain a spectrum of micronutrients that positively influence satiety. Hence, she experiences greater satiety, which has allowed her to lose weight.

- Subsequently, she also requires less basal insulin because her body weight has decreased.

It is worth noting that she required the least insulin to achieve healthy blood glucose control while losing weight.

For more on Type-1 Diabetes, see How to Optimise Type-1 Diabetes Management (Without Losing Your Mind).

A High-Fat Diet Can Worsen Insulin Resistance

The main thing I want to highlight here is that it’s not as simple as:

- carbs = bad,

- fat = good.

When everyone was chasing magical ketones, my friend Allison tried a 90% fat keto diet. Allison happens to have T1D, just like my wife and son. While on this high-fat experiment, she gained a ton of weight and her HbA1c went from 4.8% to 8.0%.

But more importantly, her daily insulin requirements doubled. She became insulin resistant because she prioritised dietary fat in pursuit of higher ketones.

Insulin became almost ineffective for her. She described injecting insulin to be ‘like injecting water’!

Fortunately, she was able to return to healthy body weight and get her HbA1c back to 4.8% after doing our Macros Masterclass and using our high-satiety NutriBooster Recipes. Here, we prioritise protein while leveraging back carbs and fat to optimise nutrient intake, satiety, and blood sugar control.

How To Lower Your Insulin and Lose Weight

Now, I want to show you how we can apply these ideas so you can lose weight and lower your insulin!

The image below shows what Moni’s closed-loop pancreas system does when her blood glucose drops below the target range. In this case, she was active and moving around, so her muscles used up the glucose in her bloodstream. This resulted in the system rapidly reducing the amount of insulin delivered so stored energy could flow into her bloodstream.

While the 99.9% of the population without Type-1 Diabetes can’t switch off our pancreas like someone with T1D—nor should we want to—we can eat in a way that will allow us to reduce our premeal glucose by:

- Reducing carbs to regain normal blood glucose variability or sugars that rise less than 1.6 mmol/L (30 mg/dL) after eating;

- Reducing our intake of fat to allow glucose to fall sooner and draw down on your stored energy;

- Prioritising foods and meals with a higher protein % and greater nutrient density to increase satiety between meals; and

- Waiting until your glucose indicates you need to refuel, as we teach in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, but not so long that your glucose falls to the point that you become starving.

Why Your Premeal Glucose is the Most Important Thing You Can Manage

Over the years of being a wanna-be biohacker and from guiding thousands of people through our Data-Driven Fasting Challenge, Macros Masterclass, and Micros Masterclass, I’ve learned that:

- We manage what we measure.

- Hence, tracking critical metrics can help guide people towards their goals.

- But most people can’t have multiple goals; they become overwhelmed and fail at all of them.

While most people focus on their glucose AFTER they eat and respond by trying to minimise how much their glucose rises, the most important thing you can do to manage your metabolic health is to optimise your PRE-meal glucose.

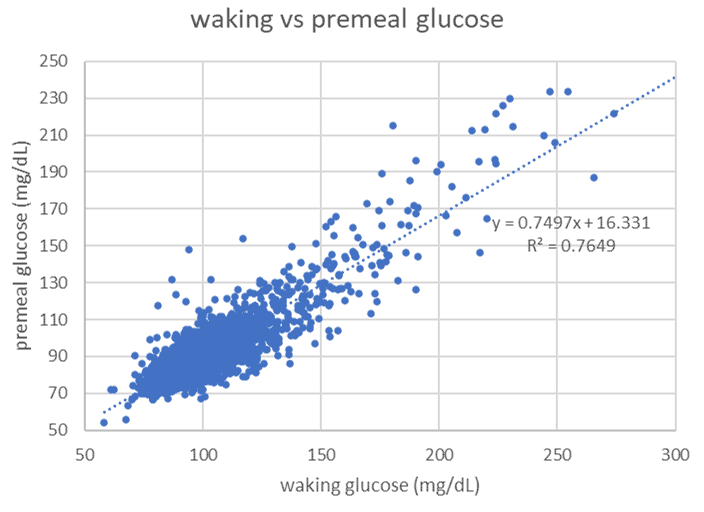

The chart below shows the average waking glucose vs premeal glucose for 4,402 Data-Driven Fasting app users. Waking glucose is a crucial marker of metabolic health and aligns closely with your glucose before you eat.

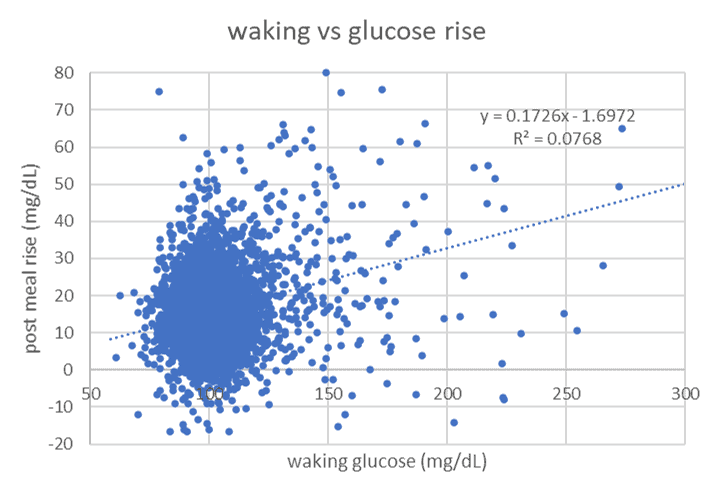

Next, we see the relationship between waking glucose and the rise in glucose after eating. There is no correlation. It’s noise!

That is, people with a lower glucose rise are not necessarily healthier! Trying to get healthier by simply reducing carbs to lower your blood glucose after you eat is useless, especially if you swap tasty carbs for tasty high-fat foods, confident in the belief that they won’t raise your insulin.

How to Lower Your Premeal Glucose and Hence Your Insulin

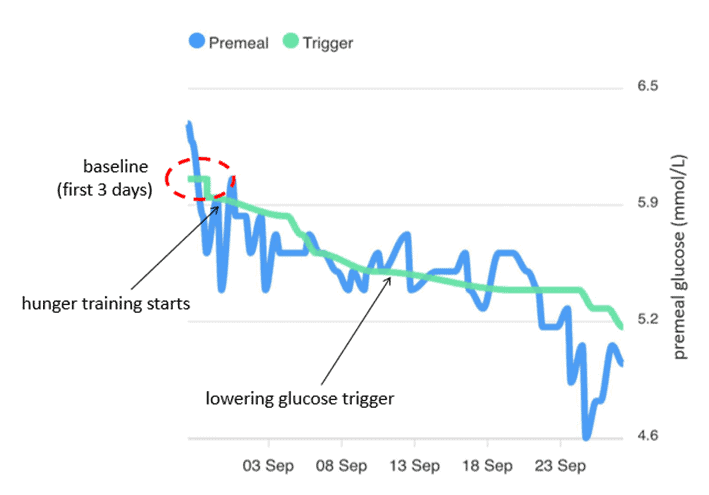

Finally, I want to show you how we use this information to guide people to reduce their premeal glucose in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges.

During the three days of baselining, participants check their glucose using a normal glucometer before they eat and record it into the Data-Driven Fasting app. At the end of the three-day baselining period, the DDF app calculates their personalised premeal glucose trigger.

From there, all someone has to do is wait until they are hungry and their glucose falls just below their trigger. If they successfully log a glucose reading below their premeal trigger, the DDF App slowly lowers their trigger, making things a little harder (but not too hard). As the body begins to offload extra energy, Your Personal Trigger will slowly decrease.

To keep progressing, participants can follow the app’s guidance on what to eat based on their blood glucose to eat again more regularly. After the Data-Driven Fasting 30-Day Challenge, they will take a break from weight loss and practice maintaining their weight.

Once they’re ready, they can start again and chase their trigger a bit lower. Over time, this leads to weight loss, lower waking glucose, and lower insulin across the day.

What’s Your Glucose Trigger?

Hopefully, you’ve found this article helpful in proactively understanding how to manage your insulin, glucose, and body weight.

If you’re interested, you can use our free Data-Driven Fasting app to calculate your personised blood glucose trigger.

Summary

- The foods most people consider ‘bad carbs’ are a hyper-palatable, nutrient-poor conglomerate of fat and carbs. These ‘foods’ stimulate a supra-additive dopamine response, which drives us to desire more foods that fill our fat AND glucose fuel tanks.

- Reducing carbs can stabilise glucose, increase satiety, and lower insulin in the short term.

- However, most of the insulin your pancreas produces throughout the day is not released to manage the food you eat.

- Rather than ‘pushing energy into your cells’, insulin’s primary role is to slow the flow of stored energy from your liver into your bloodstream so your body doesn’t disintegrate like in uncontrolled Type-1 Diabetes.

- The bigger you are, the more body fat you will have to hold back in storage. Hence, your pancreas will need to produce more insulin.

- Simply swapping carbs for fat will not improve metabolic health unless it improves body composition.

- Reducing carbs and not fearing fat can be helpful initially. However, believing fat is a free food because it does not spike insulin and eating ‘fat to satiety’ can increase body fat, which worsens insulin resistance.

- Elevated insulin and insulin resistance result from excess fat gain; it is not the cause, as many believe.

- The most important thing you can do to reverse your insulin resistance is to lower your blood glucose BEFORE you eat. This will lead to fat loss and a lower total daily insulin requirement.

- Glucose raises insulin and glucose in the short term, whereas dietary fat tends to affect blood glucose over the longer term. To achieve lower premeal blood glucose fat loss and reduced insulin, you can dial back carbs and fat while prioritising protein and nutrients in your food.

Your warning not to eat fat to satiety is so true–in the years that my husband and I were doing keto, he managed to eat his way into a gallbladder full of stones, and ended up having to have it removed. In spite of him losing 40 lbs., he can never go back to full keto again. I am guessing he went way past his personal fat threshold, and probably his personal cholesterol threshold as well, seeing as how gall stones are just concentrated cholesterol stores.

When he had to reduce and eventually eliminate his fat intake, I followed him. Using the keto tricks of using ox bile supplements before “fatty” foods (even nuts and avocado), as well as restricting added fats to coconut oil (which is digested in the small intestine–needs no gallbladder), scanning nutrition labels more effectively (watching fat vs. protein grams per serving), and doing a major pantry and grocery list over-haul. We’re both now in a groove–stable weight, stable cold tolerance, a little fat tolerance, etc. His recent labwork came back great! Mine gets done in December.

Hi Marty,

Thanks for your comments. I am certainly not a nutrition expert. Nor am I a scientist in this area. I am a surgeon who simply wants the best outcome for his patients.

I can certainly assure you that very few of my patients match the profile of your son (- 16yo, fit athlete with Type I DM. This is not the same disease as Type 2). Yes, he needs insulin.

For THEM, insulin “is the enemy” and is “making them fat”. And my simplistic 5 minute explanation resonates and most importantly, it works. Context is always key. Best wishes to you and your son.

How would you do data driven fasting without a blood glucose monitor? Im not diabetic but getting very fat. I have no access to my blood sugar numbers.

You will need a glucose monitor, but they’re inexpensive, at least compared to CGMs which are not ideal for DDF. See https://optimisingnutrition.com/getting-ready-for-the-data-driven-fasting-challenge/#htoc-2-3-what-do-i-need-to-buy1 and https://optimisingnutrition.com/getting-ready-for-the-data-driven-fasting-challenge/#htoc-2-4-would-a-continuous-glucose-monitor-be-better1

Hi Marty,

I gave the DDF approach a try, but found I was always starving as I waited for my glucose number to reduce. My family would have dinner, and I would be eating several hours later. I found the hunger and eating alone very challenging. Any thoughts?

If your goal is weight loss, there will be some hunger. The primary focus of DDF is to guide you to calibrate your hunger with your glucose, so you get to know true hunger. But DDF guides you to eat before it gets out of control and you end up binging.

In the DDF challenge we introduce the concept of the Main Meal that you can lock in around your workouts or family dinners that you eat regardless of your glucose and treat the other meals as ‘discretionary’ based on your glucose.

It’s also helpful to use your glucose to guide what you eat. This section of the quickstart guide outlines the guidance given by the DDF app on what to eat based on your glucose. https://optimisingnutrition.com/data-driven-fasting-quickstart-guide/#htoc-guidance-of-the-ddf-app

Hi Marty – great article with some very interesting new insights! Here’s something I picked up though – on those 6 x graphs showing the effect of increasing amounts of fat on blood glucose – 13g of fat seemed to lead to a sustained drop in blood glucose, at least up to 8-hours post-ingestion. Interestingly (at least to me!), this amount of pure fat corresponds to 1 x tablespoon of coconut oil or MCT oil. I am in the habit of taking a tablespoon of coconut oil at some point during my morning fast, which helps put the brakes on hunger for 2-3 more hours, allowing me to benefit from a few more hours of that lovely keto ‘mental clarity’ as well as effortlessly extending my fasting period by another 2 or 3 hours. I never take it in the ‘fed’ state though. Does this sound like a good strategy to you – or might I be adversely affecting my basal insulin levels? (I’m weight stable, in maintenance by the way).

The coconut oil sounds like a reasonable approach to tide you over and delay the next real meal. In the end it comes down to overall energy balance. If you’re not looking to lose weight and the coconut oil helps you delay your next meal it’s likely a net positive effect. I just wanted to highlight that fat is not a free food with regard to insulin and blood sugars over the long term. If you’re staying at your goal weight with that strategy and you’re getting a solid dose of nutrients in your main meals then go for it!