Embarking on a keto journey often comes with the adage, ‘Eat fat to burn fat.’ But is there more to the story, especially when it comes to a low-fat keto approach?

This article delves into the scientific intricacies of dietary fat in a ketogenic diet. Discover why eating more fat might not always be the golden ticket to weight loss and how a low-fat keto regimen might be a game-changer for your weight loss goals.

With a blend of science-backed insights and practical advice, unveil a new perspective on fat consumption in your keto journey for better, sustainable results.

Introduction

One of the most common responses to a weight-loss stall in keto groups is to ‘eat more fat to get your ketones higher and burn more fat’.

This lie is seductive because it is partially true and delicious! High-fat foods are highly palatable and provide a dopamine hit that makes us feel great and gives us a quick energy rush.

However, it’s important to understand that burning dietary fat or body fat can generate higher ketone levels. This distinction is vital if you are going to achieve your long-term goals.

Has Reducing Fat Helped Us?

Like all macronutrients, dietary fat is a controversial and divisive topic. And, as with many popular myths, there is an element of truth to the belief that eating fat will enable us to burn fat.

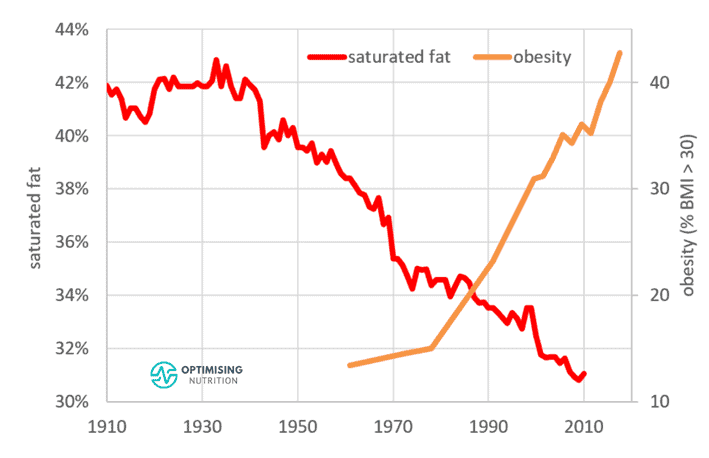

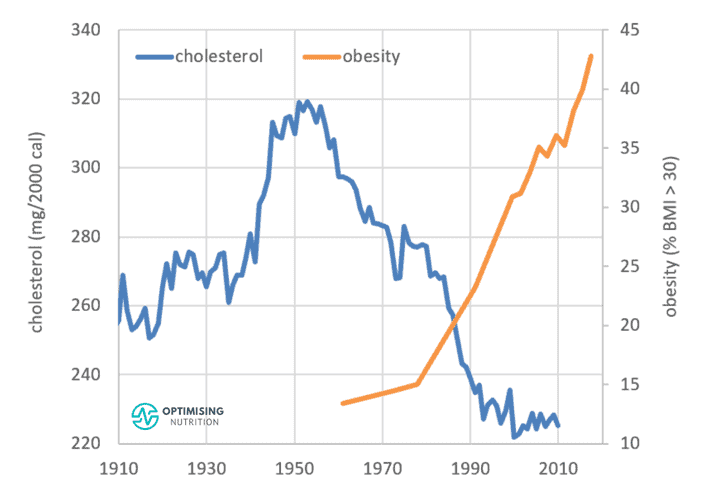

Understandably, many people have swung hard to one extreme or the other. Since the 1977 Dietary Guidelines release, we’ve been told to avoid fat, particularly saturated fat and cholesterol. However, despite obediently reducing these ‘bad foods’, the obesity epidemic has marched on unabated.

The charts below show that we have obediently reduced the percentage of energy in our diet from both saturated fat and cholesterol per the guided recommendations (data from the United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service and the Centres for Disease Control). This has been achieved by eating fewer animal products and more high-profit margin refined grains, sugars, and seed oils from large-scale agriculture.

However, reducing the amount of saturated fat and cholesterol in our diet has not helped us reverse the runaway diabesity epidemic, as the charts below show. If you were cynical, you might think that the fear of cholesterol and saturated fat was just a brilliant marketing campaign to sell more high-profit margin products made from nutrient-poor, low-satiety refined grains, sugars, and seed oils.

When we were told that we could eat fat and get skinny, many people jumped on board to swing to the other extreme believing that fat could do no wrong. However, a recurring theme of Optimising Nutrition is that the optimal is rarely found at extremes, especially when it comes to our food.

We love thinking in terms of ‘ON vs OFF’, ‘black vs white’, ‘right vs wrong’, and ‘us vs them’. But it’s rarely that simple!

The DIETFITS Study

So, does replacing carbs with fat help you to eat less and lose weight?

Let’s see what the data tells us.

In partnership with Gary Taubes and Peter Attia’s Nutritional Science Initiative, Stanford University carried out a groundbreaking, year-long major study with more than 609 participants (Effect of Low-Fat vs Low-Carbohydrate Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss in Overweight Adults and the Association With Genotype Pattern or Insulin Secretion: The DIETFITS Randomized Clinical Trial).

As shown in the charts below, the study found that participants following either a low-fat or low-carb diet achieved similar weight loss and improvements in metabolic health, regardless of genetics, insulin levels, or blood sugars.

Researchers initially encouraged participants to pursue a diet as low in carbs or fat as they could achieve. They then asked them to back off to a level that they felt was sustainable.

The key observations from the Stanford DIETFITS study were as follows:

- Following either a low-carb or low-fat diet can help reduce hyper-palatable, highly processed junk food that typically causes us to eat more than we need.

- Over time, most people gravitate back to hyper-palatable junk food, which is typically a combination of nutrient-poor fats and carbs.

- The people who changed their diet QUALITY had the most significant long-term success. These people experienced increased satiety and no longer felt like slaves to their appetites.

Lead researcher Professor Chris Gardner stated that defining diet quality to achieve satiety rather than pursuing a magic macronutrient ratio is the next exciting nutritional science frontier.

Empowering people living in the real world to gain control of their appetite will free them from weighing and measuring everything they eat and continually having to fight their hunger.

Plant-Based Low-Fat vs ‘Well-Formulated Ketogenic Diet’

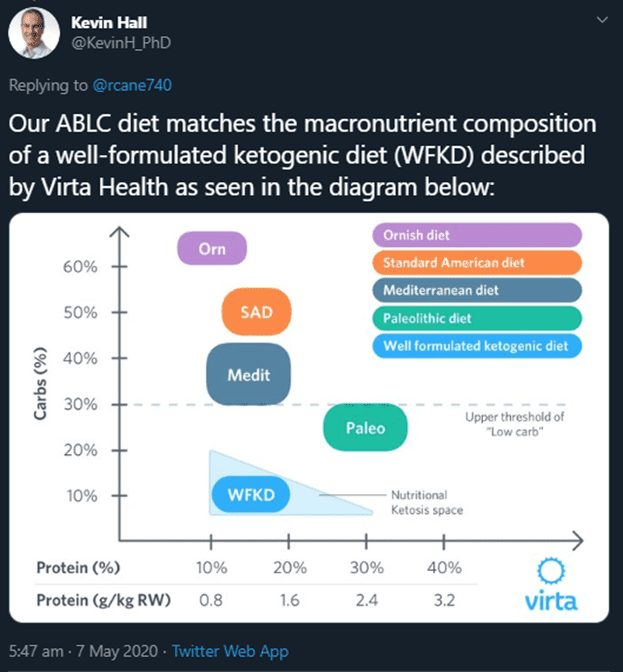

In a similar vein to the DIETFITS study, Kevin Hall’s NIH group recently published A plant-based, low-fat diet decreases ad libitum energy intake compared to an animal-based, ketogenic diet: An inpatient randomised controlled trial.

Their goal was to compare macronutrient extremes by comparing results between a 75% carbohydrate (PBLF = plant-based low-fat) diet and a 75% fat ‘well-formulated ketogenic diet’ (ABLC = animal-based low-carb).

There is no argument that the people on the keto diet were in ketosis. BHB levels reached 2.0 mmol/L towards the end of the two weeks in the low-carb population (ABLC = red line).

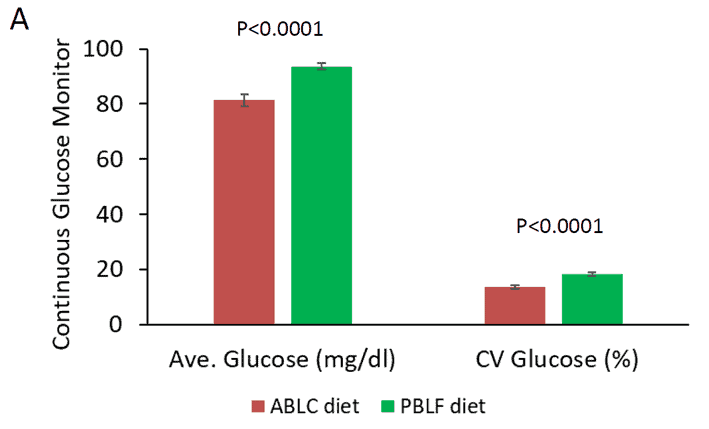

Blood glucose levels were more stable and a little lower on the low-carb diet (ABLC = red bars). HbA1c, average glucose, and insulin levels improved on both diets, but slightly more on the low-carb (ABLC = red bars).

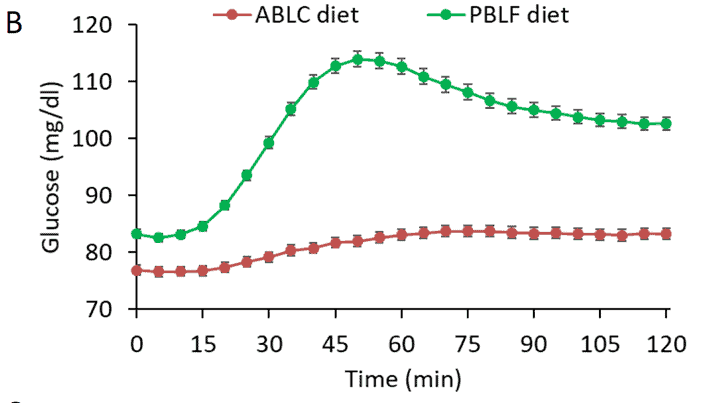

There was a flatter and smaller blood sugar response on the low-carb diet (ABLC = red line) than on the low-fat diet (PBLF = green line).

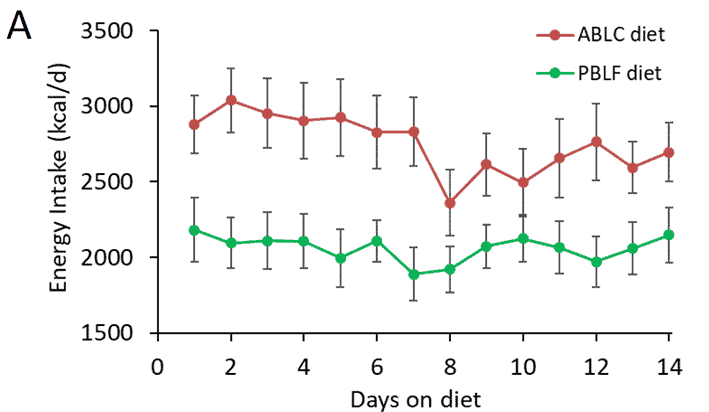

However, as per the study headline, participants averaged far fewer calories on the low-fat diet (PBLF = green line)!

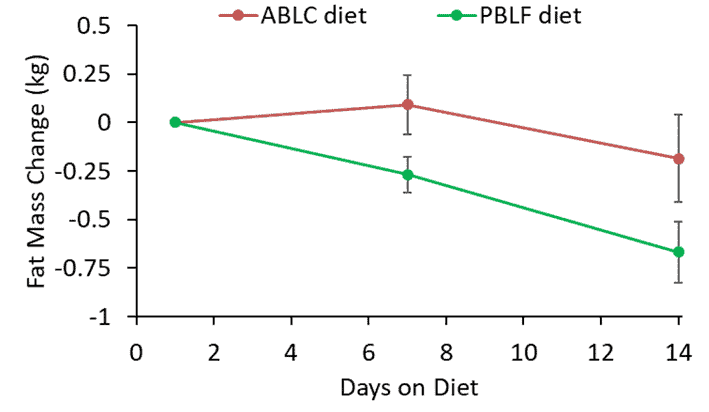

Participants on the low-carb diet lost more weight than on the high-carb diet, although the difference between them was not great enough to be statistically significant.

Weight loss on the keto approach was more water weight, whereas those on the low-fat diet lost slightly more body fat. This is because of the water weight retained with the glycogen in the liver. Note: every gram of glycogen is stored with 4 grams of water, resulting in a more significant initial weight loss as blood sugar drops.

While the Twitterverse lit up with plant-based and keto camps, with each claiming their respective team had won, the reality is the results were pretty much even. Similar to the DIETFITS study, everyone lost weight when they moved away from hyper-palatable processed foods that typically combine fat and carbs.

Why Does Low-Carb Work?

If it’s not about carbs or fat, why do we still have an obesity epidemic?

It seems we need to go beyond thinking in terms of carbs vs fat.

Unfortunately, neither study tested a control arm in the middle. I would have loved to see what would have happened if they compared it with a hybrid that contained a similar blend of carbs and fat together.

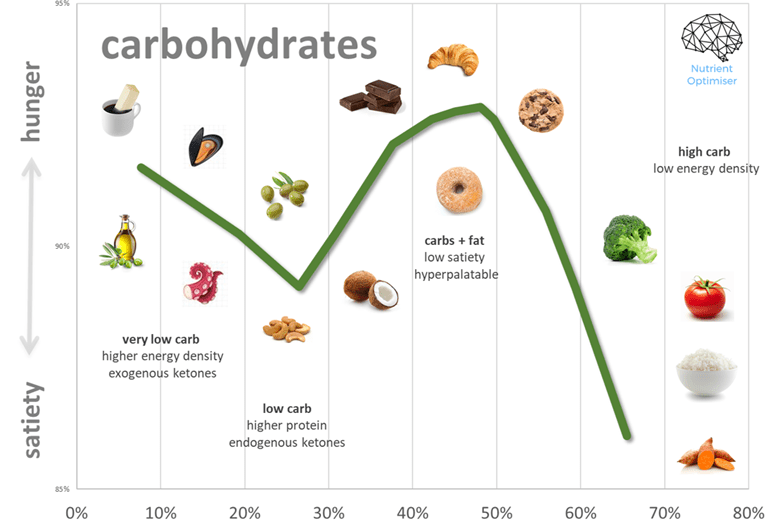

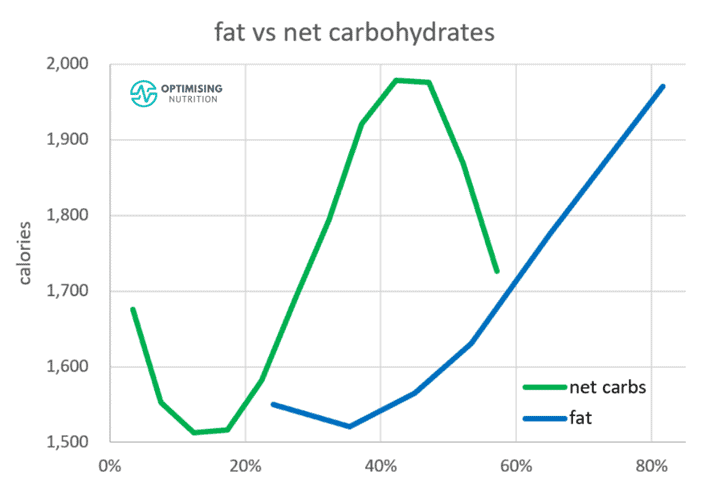

Fortunately, our satiety analysis helps to fill in these gaps. The chart below is from our analysis of 587,187 days of food logging. The vertical axis shows users’ actual calorie intakes entered into MyFitnessPal divided by their target calorie intake.

A value toward the bottom means they consumed less than their goal and vice versa. We divided the days of data up based on their carbohydrate intake (shown on the horizontal axis).

The green line indicates that we tend to eat more food when that food combines fat and carbs, like doughnuts and croissants (i.e. 40-50% carbs, with the rest of the energy from fat).

As we move toward the left, reducing dietary carbohydrates tends to help us eat less, but only up to a point. The best satiety outcome occurs when carbohydrates make up about 25% of total calories.

To the right, we see that it is tough to over-consume foods like broccoli, plain rice, and plain potato that have a very high carbohydrate content and are very low-fat.

For more detail, see Low-Carb vs Low-Fat: What’s Best for Weight Loss, Satiety, Nutrient Density, and Long-Term Adherence?

Why We Love Carb and Fat Combo Foods

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that makes us feel good. It also reinforces generally beneficial behaviours and helps us form habits that ensure our survival.

Some examples of things that produce dopamine include: eating food that contains energy tastes great because it has the nutrients we need, learning something new, sex, and other similar actions.

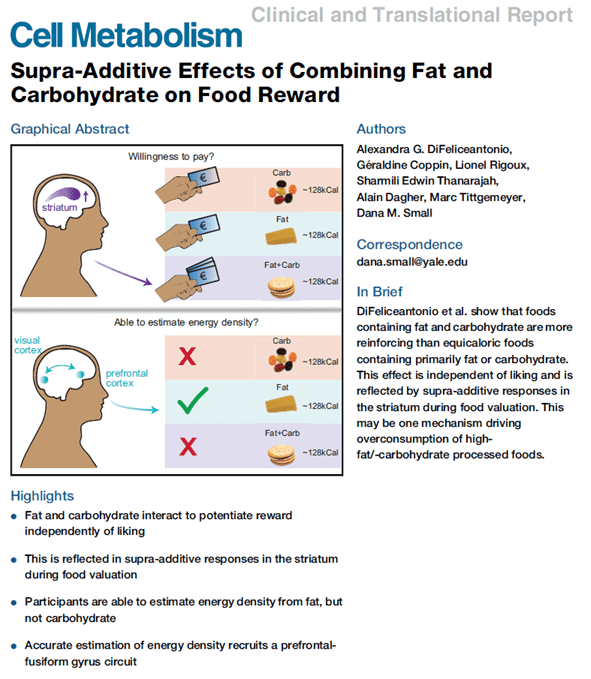

The combination of fat plus carbs provides the biggest dopamine hit because it enables us to fill our fat and glucose storage tanks simultaneously. This observation aligns with a 2018 study in Cell Metabolism that showed fat and carb foods give us a ‘supra-additive’ dopamine reward.

This relationship between energy intake and combining macronutrients also aligns with Body fat and the metabolic control of food intake (Friedman 1990).

In this study, ad libitum feeding (as much as they wanted) was used in rats. Researchers were able to conclude that ‘the signal for overfeeding originates in the liver when both fatty acids and glucose are available for oxidation’.

Our brain is programmed to seek out fat and carb combo foods and find them incredibly delicious because they are effective at getting us calories quickly and storing fat! These energy-dense foods are rare in nature other than in autumn to help animals prepare for winter. However, the fat and carb formula is the basis for most modern processed foods.

Food manufacturers and recipe book creators have perfected the art of combining refined grains and sugars with processed oils that make food palatable. Why? So, you eat more. These foods also typically contain added flavourings and colourings to trick our brains into thinking these foods contain the nutrients we require (but they don’t).

The food problem is a flavour problem. For half a century, we’ve been making the stuff people should eat—fruits, vegetables, whole grains, unprocessed meats—incrementally less delicious. Meanwhile, we’ve been making the food people shouldn’t eat, like chips, fast food, soft drinks, and crackers, taste even more exciting. The result is exactly what you’d expect.’

Mark Schatzker, The Dorito Effect: The Surprising New Truth About Food and Flavour

Many people report a spontaneous reduction in appetite when they reduce processed carbs in their diet. However, it appears that the main benefit of a low-carb, high-fat diet comes from lowering carbohydrates. This change moves us away from hyper-palatable fat and carb foods—NOT the focus of eating more fat!

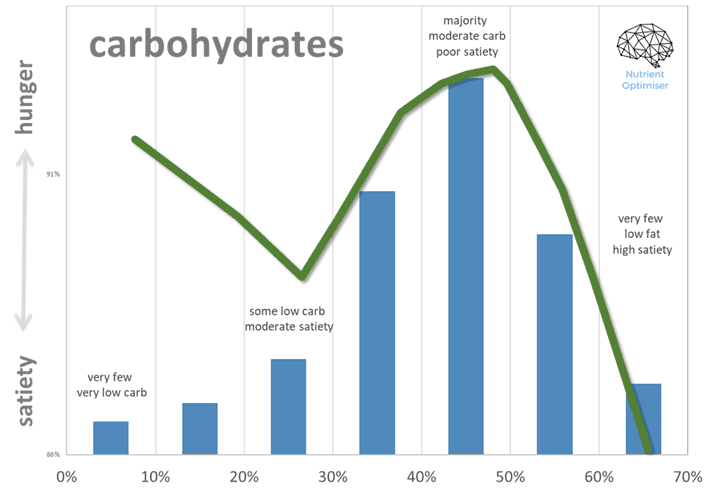

The frequency distribution (blue bars) shown in the carbohydrate vs satiety chart below demonstrates that most people gravitate to low-satiety foods that contain around 40% of their energy from carbs and a similar amount from fat.

To the right of the chart, we see that not many people manage to eat very high-carb, low-fat diets that can lead to much lower energy intake. However, groups of people follow a low-fat, whole-food, plant-based diet that demonstrates this, although the profile of bioavailable micronutrients may be less than optimal.

While it’s hard to get fat on a diet consisting only of fruit and vegetables with no added oil, it also requires a significant amount of time to prepare and consume. Thus, most people opt for convenience and add refined oils to ensure they get the energy they crave.

When we move to the left, we see that a lower-carb diet with 20–30%from carbs provides an improved satiety response and a lower ad libitum calorie intake. However, moving to an even lower carb intake is not necessarily better.

High-Fat Keto Works… Until It Doesn’t. But Then What?

Many people find that reducing processed carbs and not fearing fat in the early days of a low-carb or keto diet is helpful. Their blood sugars stabilise, and they lose a lot of water weight.

As noted earlier, you store 4 grams of water for every gram of glycogen in the liver and muscles. As a result, you also lose a significant amount of water and weight on the scale as you deplete glucose.

If you slash all your carbs and don’t replace them with fat, you’ll likely feel overly hungry, and you won’t stick with your diet. Instead, it can be wise to just reduce carbs without initially focusing on cutting fat.

Low-carb foods also tend to contain more bioavailable protein, which boosts satiety so that people feel fuller. People can then control their weight without tracking their food. They fall in love with their effortless new weight loss and believe all the benefits are from the fat they’re eating and not reducing carbs or increased protein. However, a low-carb, high-fat diet often works for a while… until it doesn’t.

Once you’ve gained the satiety benefits of more bioavailable protein and moved away from the hyper-palatable carb and fat danger zone, the hardest but most necessary step is likely to start dialling back dietary fat, too.

Like stealing a new toy from a baby, it can be hard to reduce dietary fat if we’ve been told—and subsequently believed—that we could have as much of it as we wanted. Sadly, it may be necessary if we’re going to continue to make progress in terms of fat loss and diabetes reversal.

For continued weight loss, we need to think in terms of eating to get the nutrients like protein, vitamins, and minerals we require from the food we eat while allowing excess stored energy to be used.

Is it Better to Reduce Carbs or Fat?

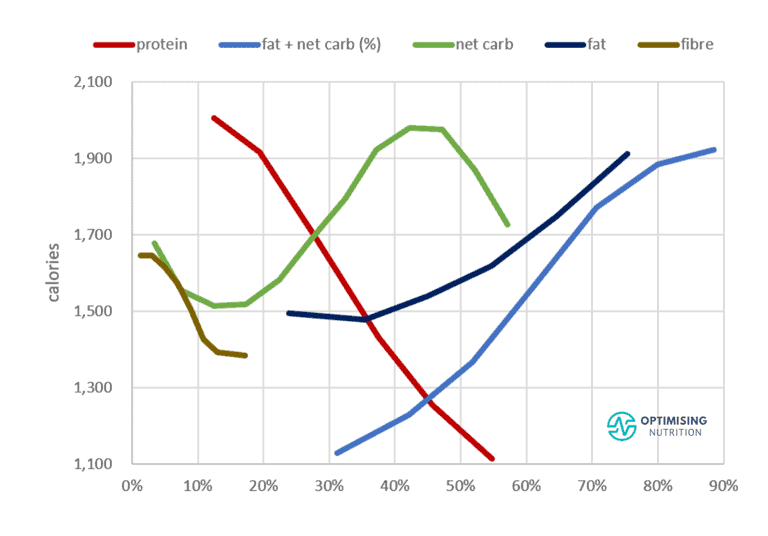

The chart below shows the satiety response to fat and non-fibre carbohydrates on the same chart showing that we achieve a similar response to reducing either fat or carbohydrates. Moving from 40-50% to 10-20% non-fibre carbs has a similar impact on how much you will eat as moving from 80% fat to 35% fat.

When we look at the satiety response to all the macronutrients together, we see that reducing the energy from fat and carbs, which increases our percentage of energy from protein, has a much more significant impact than focusing on carbs or fats alone.

As we will see in the next chapter, it’s not carbs or fat but rather the percentage of protein in our diet that is the most significant lever on our satiety and how much we will eat.

Summary

- Reducing carbs and eating ‘fat to satiety’ is a simple way to move away from the fat and carb danger zone.

- Once your progress stalls, it’s then time to reduce dietary fat. If you want to increase satiety further, manage your appetite and continue to burn body fat.

‘Eat fat to burn fat’ is poor advice that rarely leads to more optimal body composition in the long term.

Get your copy of Big Fat Keto Lies

We hope you’ve enjoyed this excerpt from Big Fat Keto Lies. You can get your copy of the full book here.

What the experts are saying

More

- Big Fat Keto Lies: Now On Kindle

- Big Fat Keto Lies: Introduction

- A Brief History of the Low Carb and Keto Movement.

- Keto Lie #1: ‘Optimal ketosis’ is a Goal. More Ketones are Better. The Lie that Started the Keto Movement.

- Keto Lie #2: You Have to be ‘in Ketosis’ to Burn Fat.

- Keto Lie #3: You Should Eat More Fat to Burn More Body Fat.

- Keto Lie #4: Protein Should Be Avoided Due to Gluconeogenesis.

- Keto Lie #5: Fat is a ‘Free Food’ Because it Doesn’t Elicit an Insulin Response.

- Keto Lie #6: Food quality is Not Important. It’s All About Reducing Insulin and Avoiding Carbs.

- Keto Lie #7: Fasting for Longer is Better.

- Keto Lie #8: Insulin Toxicity is Enemy #1.

- Keto Lie #9: Calories Don’t Count.

- Keto Lie #10: Stable Blood Sugars Will Lead to Fat Loss.

- Keto Lie #11: You Should ‘Eat Fat to Satiety’ to Lose Body Fat.

- Keto Lie #12: If in Doubt, Keep Calm and Keto On.

- Resources

Have you seen this about the pandemic MLM backlash?

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2021/01/anti-mlm-reddit-youtube/617816/?utm_source=fark&utm_medium=website&utm_content=link&ICID=ref_fark

I’m dialing back the fat as we speak.