Dive into the widely believed notion of ‘eating fat to satiety’ and unravel the truth behind its impact on our bodies.

This article sheds light on whether fat truly is the most satiating macronutrient and compares the satiety levels of carbs, fat, and protein. Through a blend of personal experiences and a deep dive into various studies, uncover the real relationship between fat, satiety, and overall nutrition.

This eye-opening analysis will not only challenge popular keto claims but also guide you towards making informed dietary choices for sustainable fat loss and better health.

Should You Just Eat “Fat to Satiety”?

This is perhaps one of the most seductive lies that I fell for in the early days of my low-carb/keto journey.

I kept hearing the keto gurus say that I should simply ‘eat fat to satiety‘. Apparently, fat was the most satiating macronutrient and the best thing I could choose to eat if I wanted to get skinny and avoid my family history of Type 2 Diabetes.

However, after putting this into practice and gaining even more fat on my body, it was time to see if this holds up against the data.

What is Satiety?

Satiety is the feeling of fullness (i.e. satisfaction) after a meal. A satiating meal will empower you to feel full with less energy (calories) and stop you from feeling hungry for longer.

Satiety is the holy grail of sustainable energy balance and fat loss.

Unless you are living in a metabolic ward with all your food provided or can track your energy in vs energy out perfectly all the time and fight against your appetite (which you can’t), prioritising foods that leave you fuller with less energy is critical to ensuring you achieve the outcomes you want.

Food manufacturers have worked out how to create foods that minimise satiety and make us eat more. However, we can reverse engineer our food choices to choose foods that will enable us to feel full and stop eating before we consume excess calories.

In addition to macronutrients (i.e. protein, fibre, carbs and fat) and micronutrients (i.e. vitamins, minerals, amino acids and fatty acids), there are other factors such as texture, smell and taste, which are all somewhat interrelated.

These factors, combined with the dopamine hit these foods provide, have ensured that we seek out these foods. However, these senses can become maladaptive to our detriment in an environment where food is cheap and plentiful and engineered for greater palatability and lower satiety.

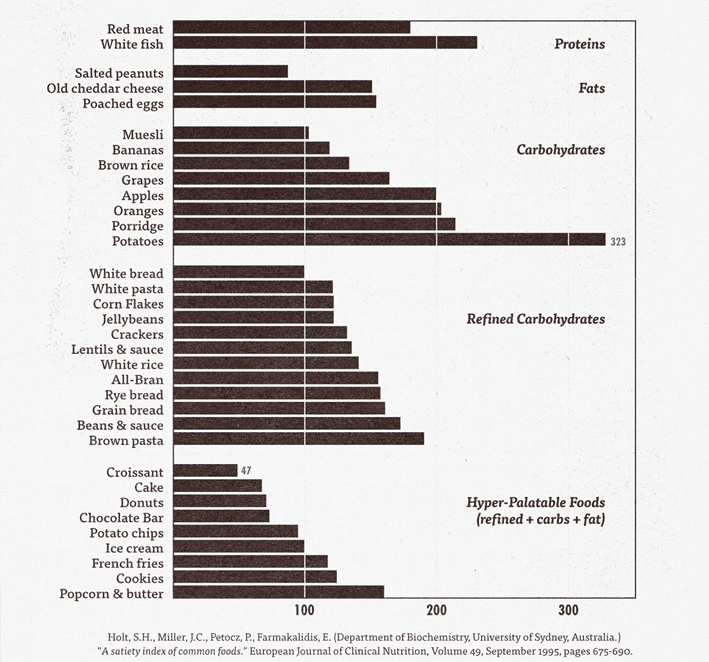

In 1995, a study at the University of Sydney quantified the satiety response to 1000 kJ (239 calories) portions of 38 different foods (refer A Satiety Index of Common Foods). The outcomes of this study are shown in the chart below.

The cooked and cooled plain potato (with lots of resistant starch) had the highest satiety response, while the croissant had the lowest. While there are only 38 data points, this laboratory data can give us a sense of how different macronutrients (or combinations) affect our satiety signals.

Does Eating More Fat Help Us Eat Less?

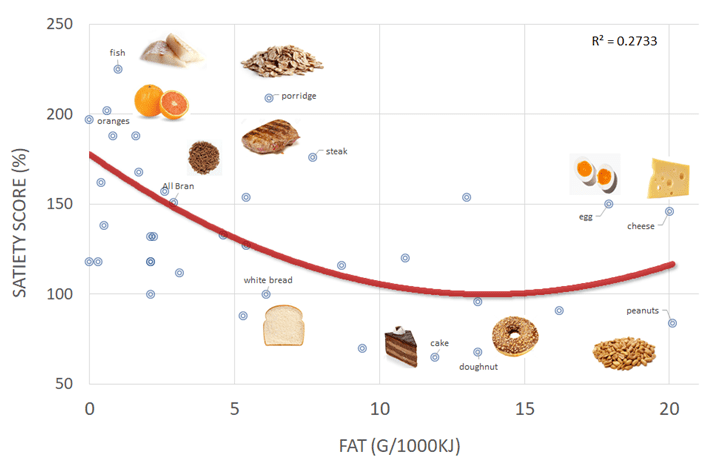

When we plot fat vs satiety score from the Holt (1995) study, we see that:

- very low-fat foods are harder to overeat;

- higher fat foods like egg and cheese are more satiating than those that are a combination of fat and carbs together; and

- foods that are a mix of fat and carbs (e.g. cake and doughnuts) are the least satiating.

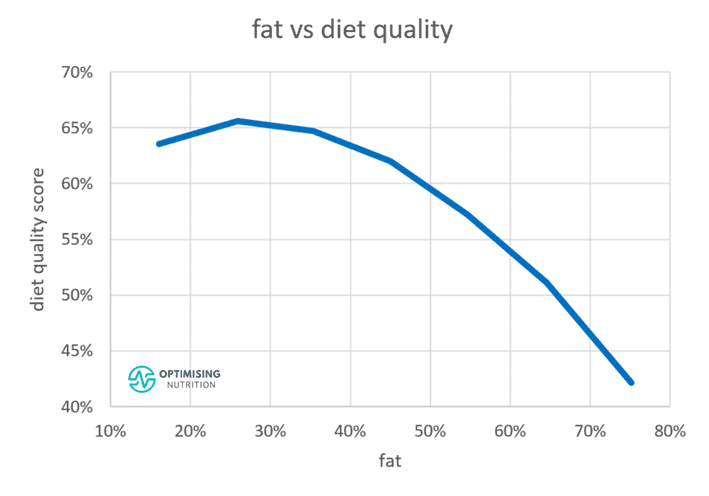

When we look at the satiety response to fat based on our analysis of half a million days of people using MyFitnessPal, as shown in this next chart, we see that lower-fat foods provide greater satiety than higher-fat foods on a calorie-for-calorie basis.

The satiety response curves from our analysis data from people using Nutrient Optimiser show a similar trend. When we consume foods with a higher percentage of fat, we consume more calories.

So, it seems the three separate data sets indicate that higher-fat foods are not satiating. Despite the common belief that you should ‘eat fat to satiety’, adding more dietary fat will not lead to greater satiety or help us to lose fat from our bodies. While eating more fat may cause us to burn more fat, the fat we burn will be from our food, not our body.

Higher Fat Foods are Not as Nutrient-Dense

When we look at fat vs nutrient density, we see that higher-fat foods tend to contain less-essential nutrients per calorie. While fat can be a great source of energy, very high-fat foods often do not provide us with as much of the nutrients we need to thrive.

Are we getting fat from eating more fat or carbs?

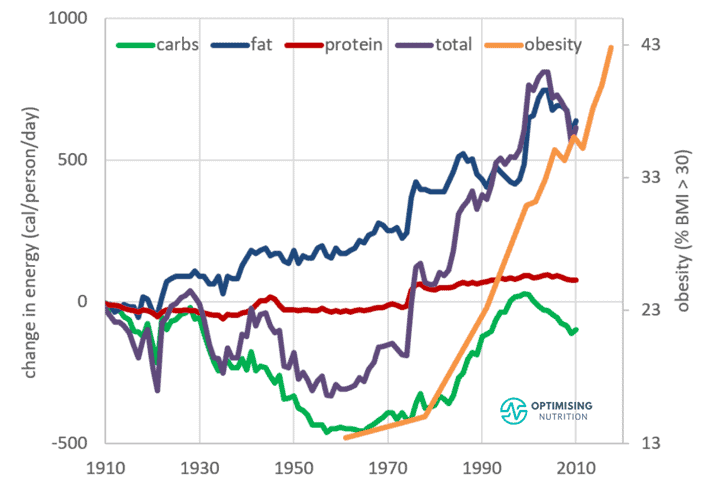

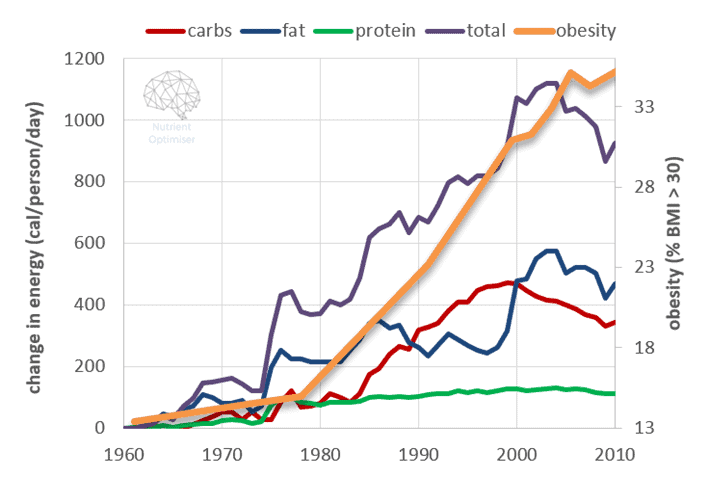

The following chart shows the change in energy from each of the macronutrients in the food system over the last century. While carbs (red line) have increased over the past 50 years, the amount of fat (blue line) has steadily increased over the past century.

Since we worked out how to extract oil from soybeans, corn and rapeseed in 1908, the amount of fat in our diet has steadily risen. Combined with the large-scale farming practices and agricultural subsidies implemented in the 1960s, the availability of calories per person (mainly from fat and carbohydrates, not protein) has skyrocketed.

The following chart shows the change in calories and obesity rates since 1960. Protein (green line) has only increased marginally, while both fat (blue line) and carbs (red line) have increased a LOT. Overall, since the lows of the 1960s, energy availability has increased by about 1000 calories per day per person in the US, with similar trends occurring across the globe.

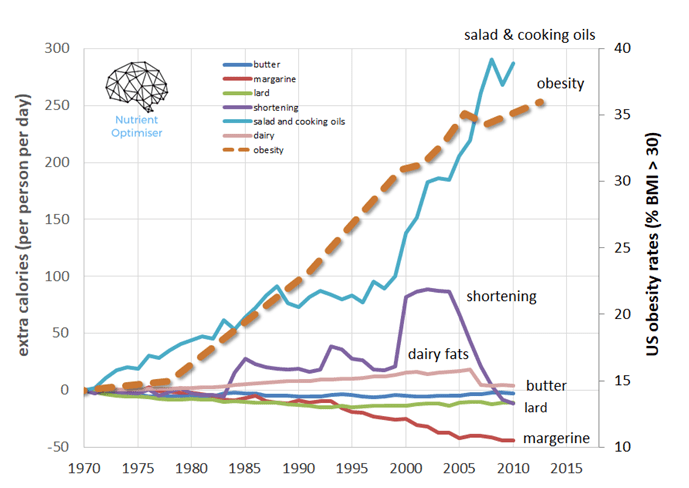

But before we declare that all fat is bad, we must look at where that extra fat has come from. When we look at the growth in fat consumed, we see the increase in ‘salad and cooking oils’ tracks closely with obesity, while animal-based added fat sources (e.g. butter, dairy and lard) have not changed significantly since 1970.

The increase in easily accessible energy from both refined grains and refined fats from large-scale agriculture is the smoking gun or the ‘elephant in the room’ of the obesity epidemic.

Omega-3 fatty acids

Things get more interesting when we look at the satiety response to each type of fat.

The chart below shows the satiety response to omega-3 fatty acids from 40,000 days of data from people using Nutrient Optimiser. Once we get an omega-3 intake of more than 3 g/2000 calories, we see improved satiety. Our satiety response to foods that contain more omega-3 fatty acids starts to taper off beyond around 7 g/2000 calories. So, there’s not much use pushing our omega-3 intake higher than this.

The most plentiful and bioavailable source of omega-3 is fatty fish (e.g. salmon, mackerel, sardines, halibut, arctic char, lingcod and caviar). While plant-based foods contain some omega-3 as alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), humans are not good at converting it to bioactive forms (i.e. DHA and EPA). Consuming fatty fish and other seafood gives us a better chance of absorbing the omega-3 into our cells where it is required.

Some examples of popular omega-3 sources (along with the amount of omega-3 they contain as a percentage of energy) include:

- caviar (23%)

- sardines (7%)

- oyster (6%)

- salmon (5%)

- mussels (5%)

- tuna (2%)

- shrimp (2%)

- scallops (2%)

- cod (1%)

However, while omega-3 is essential, you’re unlikely to get all of the satiety and health benefits from taking omega-3 supplements. Foods that are high in omega-3 provide many other beneficial micronutrients, so you should do everything you can to meet your omega-3 target from food.

Cholesterol

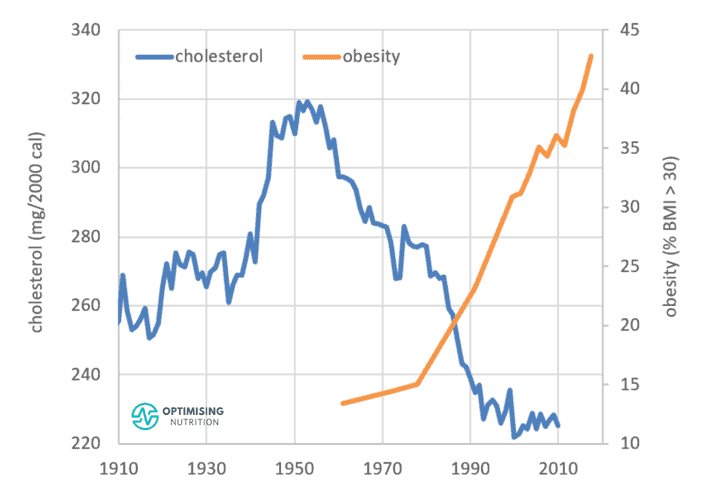

Cholesterol is a controversial nutrient with a chequered history. We need some dietary cholesterol to build our cell membranes and make hormones. However, in the past, it was thought that dietary cholesterol contributed to cholesterol in the blood, which was associated with heart disease.

The American Heart Association set a limit on cholesterol of 300 mg per day, and since the 1950s, the US population dutifully reduced their dietary cholesterol intake. Unfortunately, as you can see from this chart, this reduction in dietary cholesterol has tracked in the opposite direction of the obesity epidemic.

Interestingly, the 2015 Dietary Guidelines quietly removed cholesterol as a ‘nutrient of concern’ due to the lack of evidence that it increased the risk of heart disease, as previously thought. However, it turns out that your liver regulates the cholesterol in your blood, and the levels are not strongly correlated with dietary intake.

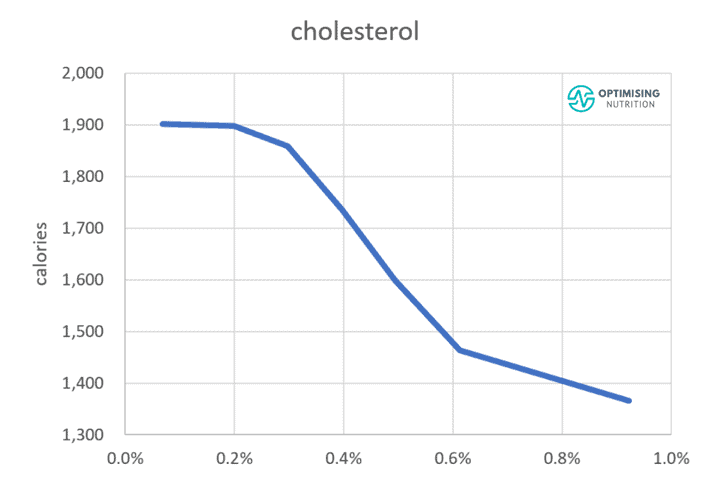

Our satiety analysis suggests that people tend to eat less when they consume food that contains more cholesterol. It appears that your body craves cholesterol and encourages you to continue eating cholesterol-containing foods until you get enough. Ironically, the lower limit targeted by the American Heart Association and the Dietary Guidelines aligns with the lowest satiety response!

Popular foods that contain more cholesterol are listed below. These are generally nutritious foods and should not be avoided due to fear of their high cholesterol content.

- egg yolk (3.0%)

- liver (3.0%)

- whole egg (2.3%)

- caviar (2.0%)

- shrimp (1.6%)

- oyster (0.7%)

- fish oil (0.5%)

- cod (0.5%)

- pork (0.4%)

- salmon (0.4%)

As with omega-3s, it’s unlikely you’ll benefit as much if you try to increase your cholesterol in the absence of whole food. Food like eggs, liver and seafood contain cholesterol in a matrix of many other beneficial nutrients. There is no reason to avoid these nutritious foods simply because they contain cholesterol.

Saturated Fat

The data from the USDA Economic Research Service indicates that our intake of saturated fat has increased over the last century, but not as much as mono and polyunsaturated fats.

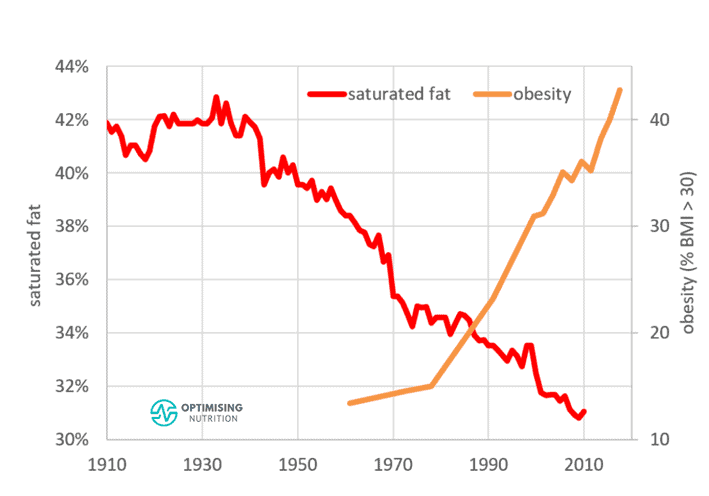

In percentage terms, saturated fat has decreased significantly since the 1930s.

Over the past half-century, our intake of foods that contain more saturated fat (e.g. dairy, butter and lard) has not changed significantly. In contrast, our use of unsaturated ‘salad and cooking oils’ (i.e. oils extracted from soy, canola and corn as used as an ingredient in our food) has skyrocketed!

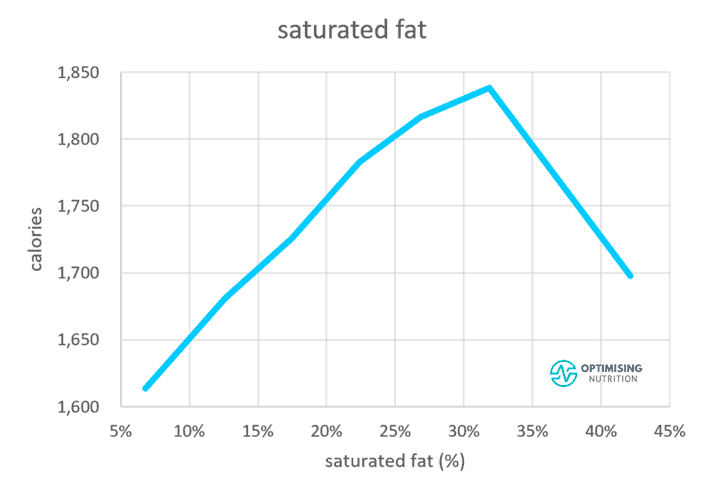

The satiety response chart shown below indicates that we eat more when we consume more saturated fat, but only up until about 30% of calories. This decrease at higher levels may be due to the fact that foods with more saturated fat also tend to contain more bioavailable protein.

Examples of popular foods that contain more saturated fat include:

- coconut oil (83%),

- butter (57%),

- lard (47%),

- Parmesan cheese (33%),

- bacon (33%),

- ground beef (27%),

- Brazil nuts (22%), and

- eggs (20%).

While you probably don’t need to prioritise more saturated fats if you are trying to lose weight, there is no need to actively avoid nutritious foods that contain saturated fat (e.g. eggs, cheese and meat).

Monounsaturated fat

Over the past century, the availability of polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats in our food system has increased by 300 to 400 calories per person per day, while saturated fat has increased by about 100 calories per day.

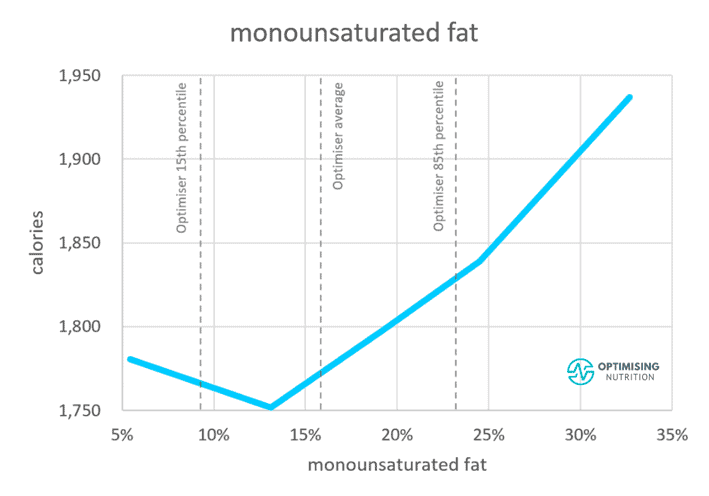

The satiety response chart below shows we tend to consume about 25% more energy when our diet contains more monounsaturated fat.

To put this into context, popular foods that contain more monounsaturated fats include:

- olive oil (74%),

- avocado oil (72%),

- avocados (55%),

- pecans (53%),

- almonds (49%),

- lard (45%),

- cashews (40%),

- peanuts (39%), and

- bacon (38%).

Although many of these are low-carb and keto favourites, they are not going to be optimal if your goal is to lose body fat. Even worse than naturally occurring fat is when seed oils are combined with starches and sugars.

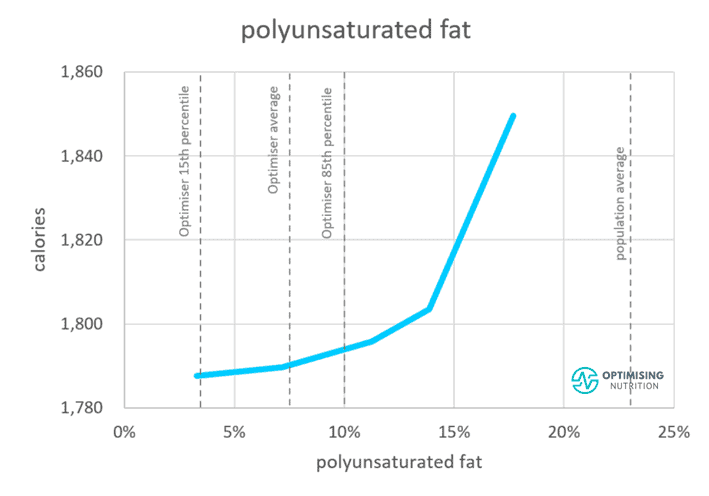

Polyunsaturated Fat

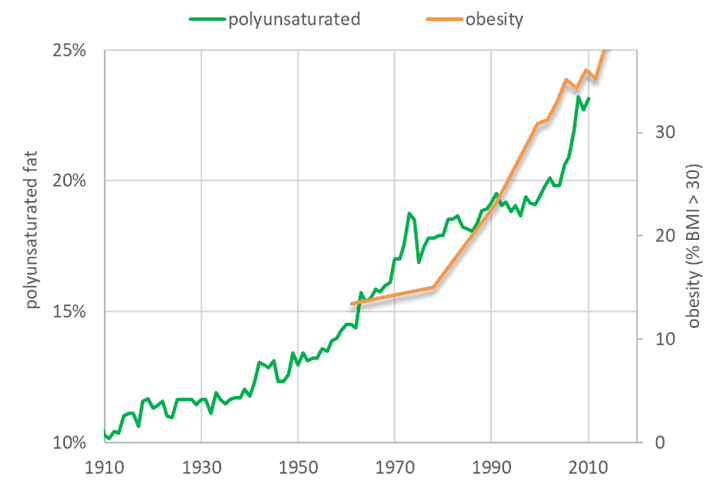

Although it makes up a smaller portion of our energy intake than monounsaturated fats, our consumption of polyunsaturated fats has followed a similar trajectory over the last century.

Our analysis shows that calories increase rapidly once polyunsaturated fats contribute more than 10% of calories.

Popular foods that contain more polyunsaturated fat include:

- walnuts (65%),

- mayonnaise (59%),

- flaxseeds (48%),

- Brazil nuts (33%),

- pecans (28%), and

- peanuts (33%).

As an aside, an interesting study looked at the response to 70% fat diets with high levels of polyunsaturated fats vs. saturated fats (see Differential metabolic effects of saturated versus polyunsaturated fats in ketogenic diets). Participants saw more elevated blood ketones, lower glucose and better insulin sensitivity on the diet that provided more energy from polyunsaturated fats compared to saturated fats.

According to Dr Tommy Wood, it appears that polyunsaturated fats allow us to eat more and put on more body fat before we exceed our Personal Fat Threshold and become insulin-resistant. A ketogenic diet consisting of less saturated fat and more polyunsaturated fat may be helpful if your goal is simply to maximise ketone levels for therapeutic purposes. However, it may not be ideal for body composition or long-term health.

A diet with less unsaturated fat may help raise our Personal Fat Threshold so we don’t become insulin-resistant and develop Type 2 Diabetes as quickly.

However, our satiety analysis indicates that unsaturated fats may also drive us to consume more energy from refined fat, which will cause us to gain fat more quickly and eventually reach our Personal Fat Threshold.

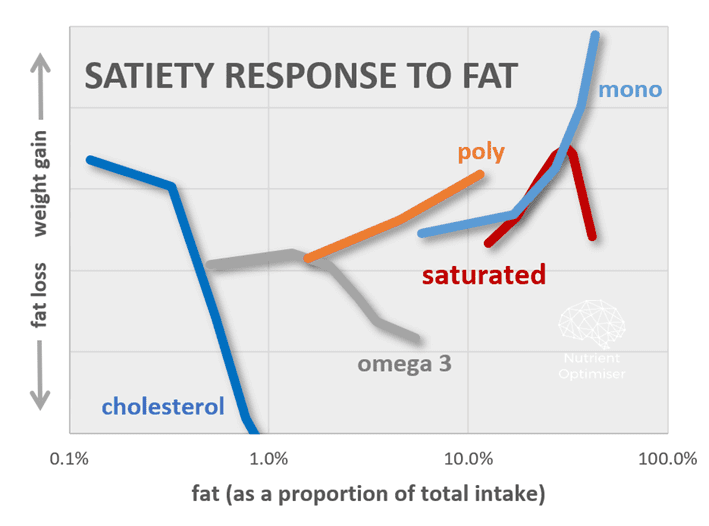

Summary

To bring all this together, the chart below shows the satiety response curves plotted on one chart.

- Foods that contain more omega-3 fatty acids and cholesterol tend to be more satiating. Avoidance of foods that are otherwise nutritious and contain energy, such as cholesterol or omega-3, may have a negative impact on satiety.

- Monounsaturated, saturated, and polyunsaturated fats all have a negative impact on satiety. However, monounsaturated fat tends to align with the greatest energy intake.

Get Big Fat Keto Lies!

Get your copy of Big Fat Keto Lies here.

More

- Big Fat Keto Lies: Introduction

- A Brief History of the Low Carb and Keto Movement.

- Keto Lie #1: ‘Optimal ketosis’ is a Goal. More Ketones are Better. The Lie that Started the Keto Movement.

- Keto Lie #2: You Have to be ‘in Ketosis’ to Burn Fat.

- Keto Lie #3: You Should Eat More Fat to Burn More Body Fat.

- Keto Lie #4: Protein Should Be Avoided Due to Gluconeogenesis.

- Keto Lie #5: Fat is a ‘Free Food’ Because it Doesn’t Elicit an Insulin Response.

- Keto Lie #6: Food quality is Not Important. It’s All About Reducing Insulin and Avoiding Carbs.

- Keto Lie #7: Fasting for Longer is Better.

- Keto Lie #8: Insulin Toxicity is Enemy #1.

- Keto Lie #9: Calories Don’t Count.

- Keto Lie #10: Stable Blood Sugars Will Lead to Fat Loss.

- Keto Lie #12: If in Doubt, Keep Calm and Keto On.

- Resources