As you embark on a ketogenic journey, understanding the role of protein gluconeogenesis is crucial.

This article unravels common myths, helping you gauge how much protein to consume on keto without fearing gluconeogenesis.

Discover if gluconeogenesis is a friend or foe and whether it could potentially kick you out of ketosis or if it’s a natural process aiding your dietary endeavours.

- Should You Avoid Protein Due to Gluconeogenesis?

- How Do We Measure Protein Intake?

- What Is the Absolute Minimum Protein Intake Required?

- The Minimum Amount of Protein to Prevent Diseases of Deficiency

- Minimum Protein to Grow Muscle

- How Much Protein Do You Need to Prevent Muscle Loss?

- Does Protein Raise Blood Sugars?

- Insulin Dosing for Dietary Protein

- Adjusting Diabetes Medications

- Why Protein Percentage Is More Useful

- Will Too Much Protein ‘Kick Me Out of Ketosis’?

- Protein vs Nutrient Density

- What About Protein Powders?

- Is Too Much Protein Bad for My Kidneys?

- What About ‘Rabbit Starvation’?

- Summary

- Get your copy of Big Fat Keto Lies

- What the experts are saying

- Get Big Fat Keto Lies!

- Sample the Other Chapters of Big Fat Keto Lies

Should You Avoid Protein Due to Gluconeogenesis?

Perhaps the biggest differentiator between keto and other successful versions of a lower-carb diet like Atkins, Paleo, Bernstein, Banting, and Carnivore is the misguided fear that ‘excess protein’ keeps ketones low and insulin high through the process of gluconeogenesis.

Ever since Jimmy Moore broadcasted the idea that protein could convert to sugar via gluconeogenesis and, therefore, lower blood ketones, it seems that many low-carb and keto groups have been confused about and afraid of protein. Many keto gurus recommend doing whatever you can to minimise protein and replace those calories with fat to maximise ketosis.

When we were both speakers on the 2016 Low-Carb Cruise, Jimmy told me that he aims for Dr Ron Rosedale’s recommendation of 0.8 g/kg protein. He has encouraged his followers to do the same in fear of protein ‘turning into chocolate cake in your bloodstream‘.

Sadly, many of these people can’t work out why their weight loss has stalled with the belief that protein is bad and fat is good, despite ‘doing everything right’.

How Do We Measure Protein Intake?

Before we get into recommended protein quantities, we should touch on how protein intake is measured. A lot of confusion comes from mixing up the different units used to measure protein. However, the reality is that people are often talking about almost the same protein intake in practice.

The table below shows some examples of different protein recommendations. People talk about protein in terms of body weight, lean body mass (LBM), ideal body weight, or percentages. Some people talk about protein per kilogram, while others talk about it per pound.

| Metric | Pros | Cons | |

| Total body weight | g/kg BW g/lb BW | Easy to measure because most people don’t measure their body fat. | Doesn’t consider body fat that is less metabolically active. |

| Lean body mass (LBM) | g/kg LBM g/lb LBM | More accurate because it accounts for active lean tissue. | Requires some understanding of body fat levels. |

| Ideal body weight/Reference body weight | g/kg IBW g/lb IBW | Doesn’t require the measurement of body fat. | Difficult to agree ideal body weight. |

| Percentage of calories | % | Simple | Doesn’t account for whether you are in an energy surplus or deficit. |

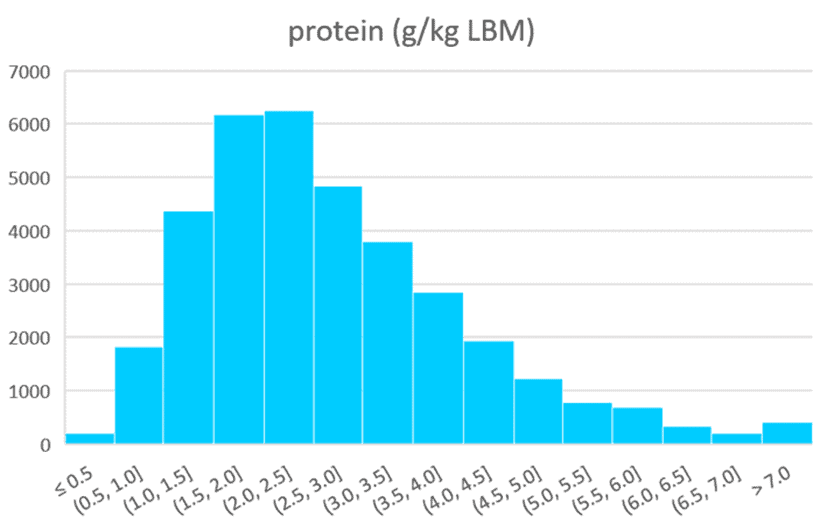

Our preference is to use protein per unit of lean body mass (i.e. g/kg or g/lb LBM) because it’s your muscles and organs that are metabolically active. On the contrary, your body fat is, for the most part, just your fuel tank that comes along for the ride.

You can use a DEXA scan bioimpedance scale or comparison pictures (like the ones below) to estimate your level of body fat (% BF). DEXA scans are expensive but accurate, whereas bioimpedance scales and comparison pictures are easy to do at home to compare your progress.

If you’re interested, you could calculate your LBM using the following formula:

lean body mass (LBM) = bodyweight x (100% – %BF) / 100%.

Calculating your body fat levels or protein intake with a high degree of accuracy is unnecessary for most people, given that their protein target should generally be treated as a minimum.

To quickly calculate your target protein intake, you can use the simple macro calculator here.

What Is the Absolute Minimum Protein Intake Required?

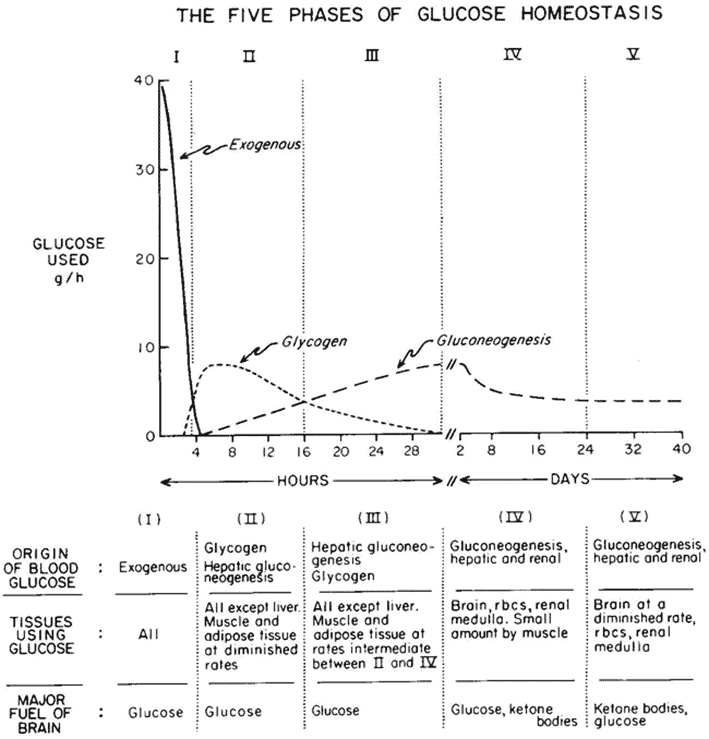

According to Cahill’s starvation studies, we burn about 0.4 g/kg LBM per day of protein via gluconeogenesis during prolonged starvation.

After we burn through the food in our stomach and the glycogen stores in our liver and muscles, the body will turn to its internal protein stores from muscles, organs, and, to a lesser extent, the glycerol backbone of fatty acids to obtain glucose via gluconeogenesis.

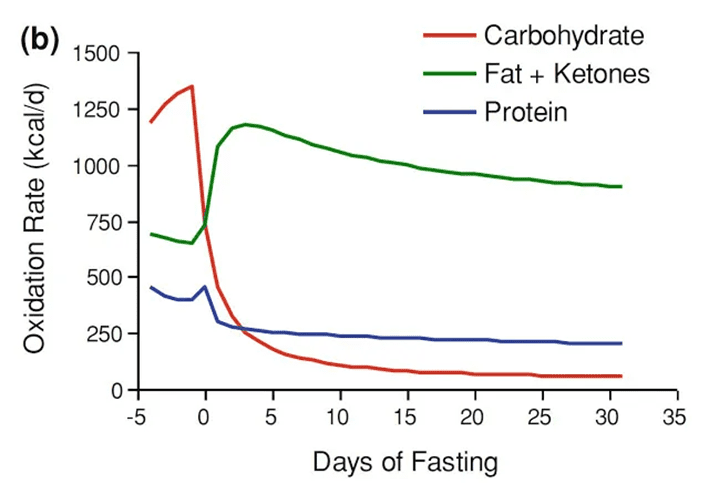

The figure below shows how we use less protein for energy the longer we go without food (from Quantitative Physiology of Human Starvation: Adaptations of Energy Expenditure, Macronutrient Metabolism and Body Composition). After a couple of days without food, fat supplies and ketosis kick in to supply the energy deficit.

In the first few days, you will be using around 400 calories from protein or about 100 grams of protein per day. Over the long term, this decreases to 250 calories worth or roughly 60 grams of protein per day.

While protein requirements reduce during extended fasting, this amount of protein you are pulling from your muscles and organs is still significant. Therefore, if you fast for a couple of days every week, you will need to make up for that protein across the week to prevent a long-term loss of lean muscle.

When you refeed, your body will seek out foods to replenish the energy and nutrients it has lost. So, if you do not prioritise protein when you refeed, you will consume more energy to get the protein that your body requires as your body drives you to eat more. But the unfortunate reality is that when we get ravenous after not eating for a long time, we tend to gravitate to energy-dense, lower protein foods, so we struggle to make up for our protein deficit after fasting.

This is why so many people lose and regain the same weight when they attempt extended fasting without paying attention to food quality when they refeed. Regardless of how long you choose to fast, nutrient-focused refeeding (especially protein!) is critical.

Over the short term, gluconeogenesis and autophagy are not necessarily bad. Your body increases autophagy (self-eating) to use the old, sick, and redundant body parts as fuel. After a fast, the body is primed, highly insulin sensitive, and ready to build new muscle.

The reality is that most people see their lean mass drop during any form of energy restriction. This includes extended fasting. It’s ideal if you can keep an eye on your changes in lean mass over time.

While no method of measuring body fat is entirely accurate, tracking your change against your baseline with tools like bioimpedance scales that you can use at home every day will give you an understanding of whether you should increase your protein intake if you find you are losing muscle rather than fat.

The Minimum Amount of Protein to Prevent Diseases of Deficiency

The Daily Recommended Intake (DRI) for protein is 0.84 g/kg of body weight (BW), while the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) is 0.68 g/kg BW. However, it’s critical to keep in mind that the DRI is a recommended minimum amount needed per day to prevent diseases of protein deficiency.

Recent studies have indicated that higher quantities of protein may be necessary, especially in older people. They may require up to 1.2 to 2.0 g/kg of BW of protein per day to optimise physical function.

According to Raubenheimer and Simpson, older people require more dietary protein because they are more likely to be insulin resistant. Thus, they are more likely to have excessive levels of gluconeogenesis (Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis), causing the protein they eat to be transformed and ‘lost’ as glucose in the bloodstream.

On another note, your body will make the glucose it needs from the protein you eat if you are only consuming minimal amounts of carbs. Hence, you may require extra protein to supply your body with the glucose it needs. If you don’t prioritise adequate dietary protein, your appetite will increase to ensure you get enough protein, even if you have to consume more energy than you require.

Rather than avoiding protein, it’s better to target a higher protein percentage (protein %) if your goal is to lower your insulin, reduce body fat, and improve your insulin sensitivity. A diet with a higher protein percentage also improves satiety. In time, it can lead to fat loss, lowered blood sugar, and normalised insulin levels.

Minimum Protein to Grow Muscle

You’ll need more protein for growth and repair if you’re active. If you’re sedentary, you’ll need less. Most of the time, our appetite sorts this out for us, and we may crave more protein if we are doing a lot of resistance training. If you’re active, your appetite for protein will likely increase to ensure you get enough of it to prevent muscle loss.

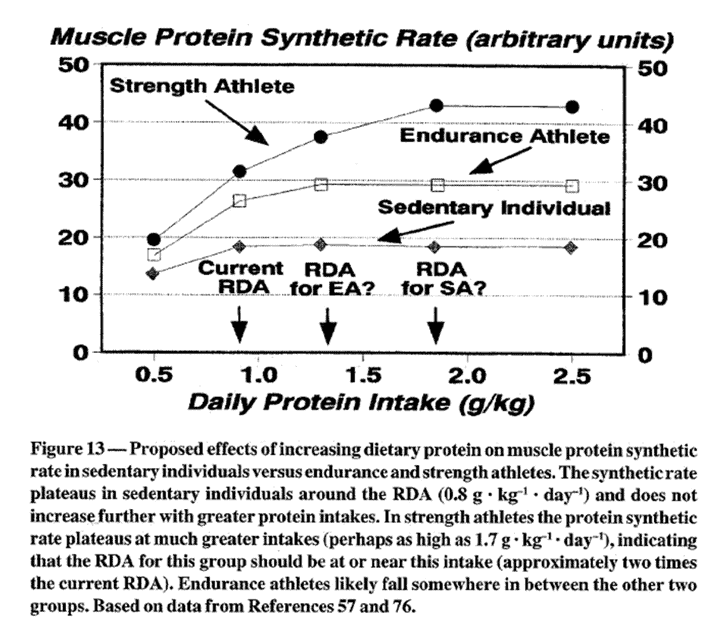

As shown in the figure below from the study, Effects of Exercise on Dietary Protein Requirements (Lemon, 1999):

- a strength athlete requires at least 1.8 g/kg body weight to maximise muscle protein synthesis;

- an endurance athlete should consume at least 1.4 g/kg body weight; and

- someone who is sedentary needs at least 0.9 g/kg body weight.

Note: These values should be seen as minimums during weight maintenance. More protein may increase satiety, improve nutrient density, and decrease the loss of lean mass when losing fat.

How Much Protein Do You Need to Prevent Muscle Loss?

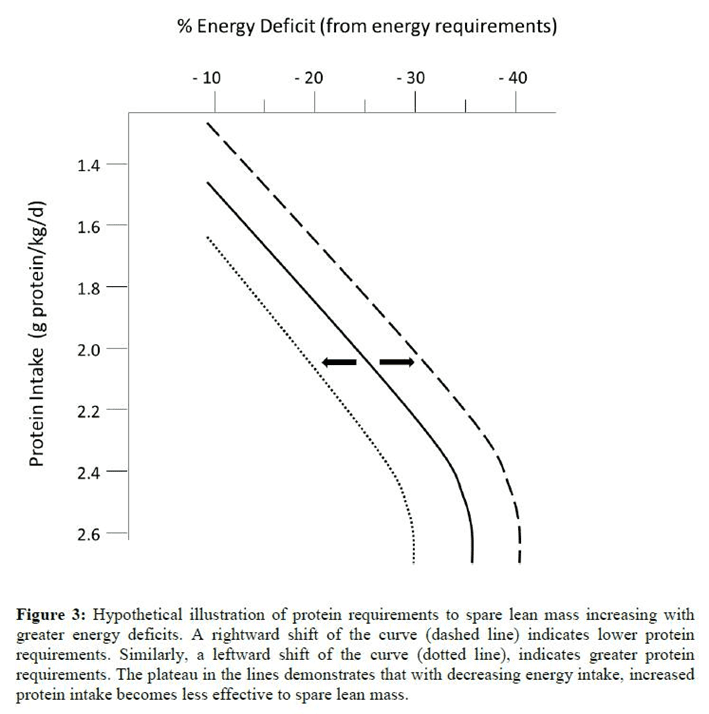

If you are active or incorporating resistance training, you will have a greater protein requirement in an energy deficit for fat loss. Using data from a review paper by Stuart Phillips, lean muscle mass is best preserved when we have at least 2.6 g/kg total body weight with an aggressive deficit (e.g. 35%). On the contrary, a lower protein intake of 1.5 g/kg body weight seems adequate where we have a less aggressive deficit.

Does Protein Raise Blood Sugars?

Many people are concerned that protein will raise their blood sugars. However, foods with more protein are often lower in carbohydrates, which tend to drive up blood sugars the most. This is shown in the chart below from our analysis of the Food Insulin Index data.

Foods relatively higher in protein also tend to displace carbohydrates in the diet. Our analysis of the Food Insulin Index data also shows that protein does not influence blood sugars post-meal (see What affects your blood sugar and insulin (other than carbs?).

While protein can be converted to glucose, this does not occur immediately. When you eat protein, your pancreas secretes glucagon. Glucagon pushes liver glycogen into your bloodstream as glucose. The glycogen response is balanced by insulin, and blood sugar thus remains stable for most people.

Many metabolically healthy people find their blood sugars decrease after a high-protein, low-carb meal because of the insulin response they get from protein. This is especially true after a high-protein morning meal when their body is primed to store energy after an overnight fast.

Conversely, people who are insulin resistant may find the insulin they release in response to protein does not act as effectively to balance the glucagon. As a result, they may see their blood sugars rise.

Some people see this rise in blood glucose as a reason to avoid protein. Because a significant amount of their dietary protein is being used to supply the glucose they need, they must instead shift their focus to getting enough protein to ensure enough amino acids are available for muscle protein synthesis and other critical bodily functions. This excess gluconeogenesis can cause their appetite to ramp up to ensure they get the protein they need.

If you see your blood sugars rise significantly after a low-carb, high-protein meal, you likely have a significant amount of insulin resistance because you are above your Personal Fat Threshold. Rather than avoiding protein and prioritising fat in a misguided effort to improve your insulin resistance, you actually need to do the opposite!

Insulin Dosing for Dietary Protein

Type-1 Diabetics following a low-carb diet know that they require extra insulin for dietary protein as well as carbohydrates.

Because insulin works to build and repair your muscles and keep your stored energy locked away while eating, you will need a little extra insulin several hours after consuming a high-protein meal.

Over the first three hours, protein requires about half as much insulin as carbohydrates. However, as we will learn later, the fact that protein requires bolus insulin, or the insulin associated with the food we eat, should not be of concern.

Protein promotes satiety, which will allow your stored body fat to be used. Protein will also reduce your basal insulin requirements and total insulin demand throughout the day.

Adjusting Diabetes Medications

Injected insulin helps manage the symptoms of Type-2 Diabetes, like elevated blood sugars, but it does little to reverse the underlying cause of energy toxicity. In addition, because insulin is the hormone that tells our liver to hold back energy in storage, exogenous insulin also tends to make it harder to lose unwanted body fat.

Injected insulin forces your body to hold fat in storage, resulting in hunger and resultant weight gain. As you lose weight, you will see your need for both injected basal and bolus insulin reduce as you lose excess body fat and improve your insulin sensitivity.

If you are taking any diabetes-related medications like injected insulin, you should pay particular attention to your blood sugars and work with your healthcare team to adjust your medications to ensure that your blood sugars don’t go lower than 4.0 mmol/L (72 mg/dL). You will not only feel unwell below this level, but you will likely want to eat anything, and everything until your blood sugar returns to normal.

Establishing a predictable routine is crucial if you are taking diabetes medications. If you radically change your eating pattern by suddenly skipping a whole day of eating or engaging in multi-day fasts, your insulin needs will plummet, and you will risk low blood sugar or hypoglycemia.

Why Protein Percentage Is More Useful

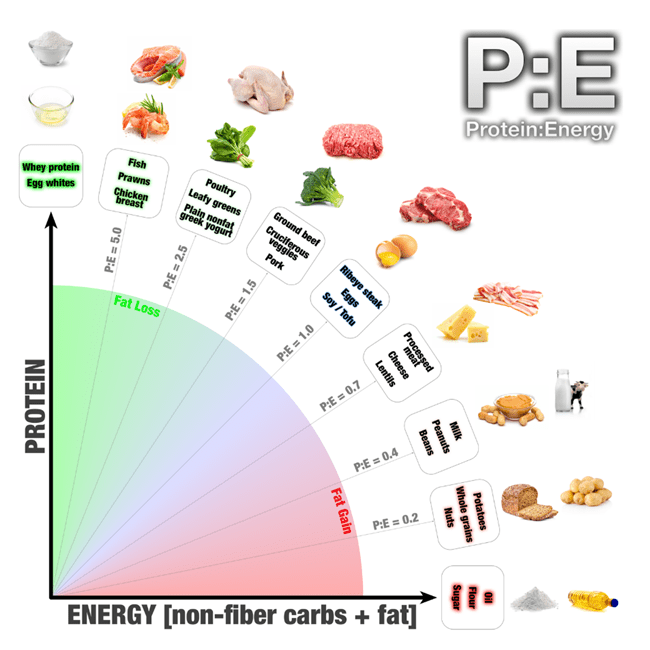

Optimising Nutrition advisor Dr Ted Naiman has recently been advocating for more intelligent consideration of the Protein:Energy Ratio (P: E). This ratio is based on the Protein Leverage Hypothesis, which demonstrates that all living organisms, including humans, eat until they get the protein they need.

Optimising the macronutrient composition of your diet for greater satiety is the key to managing your food intake with less willpower and self-imposed deprivation.

- The key to increasing satiety and eating less is to increase your protein PERCENTAGE (protein %), or your amount of total calories from protein.

- Conversely, the way to eat more to grow and fuel high activity levels is to decrease your protein percentage by increasing your intake of energy from fat and carbs.

Our analysis of half a million days of data from MyFitnessPal users and 125,761 days of macronutrient and micronutrient data from 34,519 people who have used Nutrient Optimiser further supports the Protein Leverage Hypothesis.

Of all the quantifiable factors, protein percentage of your diet has the most significant impact on satiety of all the macronutrients and essential micronutrients. And yes, we have tested them all!

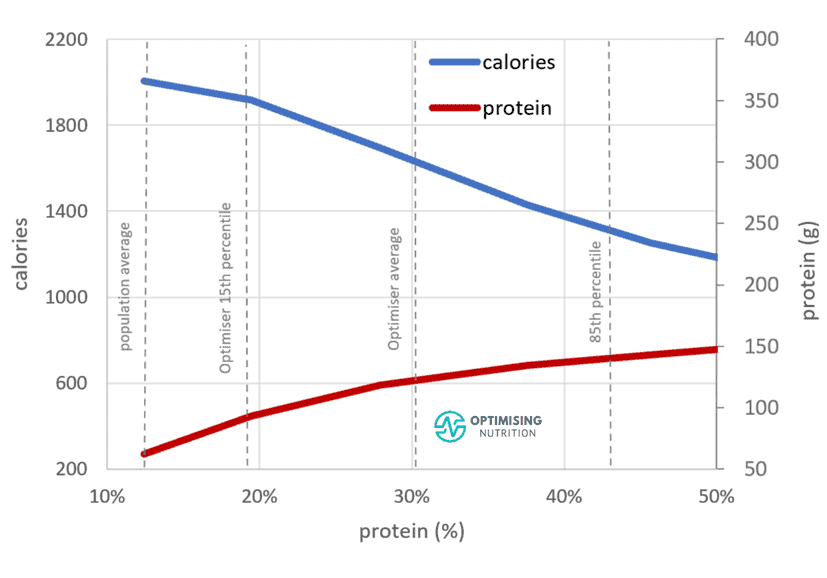

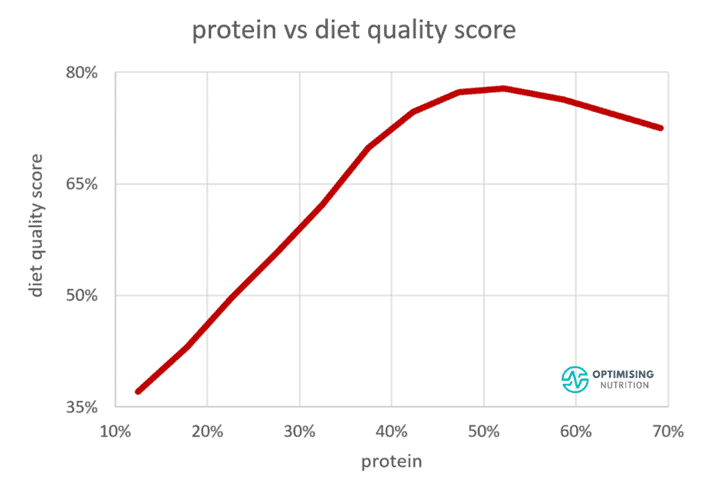

The chart below shows the relationship between protein % and calorie intake from our Optimiser data, showing that as we move from a low protein % to a high protein %, we tend to consume 55% fewer calories!

Managing your appetite and spontaneously eating less is not necessarily about eating more protein. Instead, you can incrementally dial up the percentage of protein in your diet by reducing your intake of fat and carbs while prioritising protein.

The chart below shows the relationship between protein %, protein (in grams), and total calorie intake. Moving from 15% to 50% protein aligns with:

- a total reduction of 800 calories,

- an increase in protein of 75 g (or 300 calories), and

- a reduction of 1100 calories from fat and carbs.

By contrast, many low-carb or keto communities advocate the exact opposite to break a fat loss stall, recommending that you avoid protein because of its short-term impact on insulin and eat more fat to increase ketones. Meanwhile, many in the low-fat or plant-based communities also recommend actively avoiding protein for various reasons.

Although we live in a postmodern world where everyone is entitled to their own opinion that may be overly skewed from their own personal social media feed, science and human metabolism are the same regardless of our beliefs.

Our data analysis of 125,761 days of macronutrient and micronutrient data from 34,519 people who have used Nutrient Optimiser also shows that our overall calorie intake decreases as our percentage of protein increases. It is challenging to overconsume foods with a higher percentage of protein. Sadly, the average population’s 13-15% protein intake aligns with the lowest satiety response.

However, it’s not sustainable to jump from 10 to 50% of your total calories from protein overnight. Instead, slowly increasing your protein percentage by dialling back readily accessible energy from fat and carbohydrates is a more sustainable way to lose fat from your body.

Analysis of our data from Nutrient Optimiser users shows that most people prioritising nutrient density consume around 1.8 g/kg LBM protein. In our Macros Masterclass, we tend to see the best satiety response and the quickest weight loss when people consume this amount of protein as a minimum and dial back their fat and carb intakes progressively.

Prioritising adequate dietary protein ensures you don’t lose precious, metabolically active muscle and other crucial lean mass like your vital organs. Reducing dietary carbs helps decrease blood sugar variability, whereas reducing dietary fat helps promote body fat loss and leads to lower blood sugars over the long term.

Will Too Much Protein ‘Kick Me Out of Ketosis’?

Studies tend to be mixed on whether higher levels of protein decrease ketones. However, many people anecdotally report that their ketones do decrease with higher levels of dietary protein.

This makes logical sense, given that protein provides oxaloacetate. Oxaloacetate enables fat to be burned in the citric acid cycle rather than through ketosis, which is a less efficient process. However, you must consider your goals to understand whether or not you need to be concerned about decreased ketones.

- Do you want to achieve exogenous ketosis, or measurable amounts of ketones from added dietary fat so that you can achieve therapeutic levels of ketones for the management of epilepsy, Alzheimer’s or dementia, or;

- are you aiming for endogenous ketosis, where the body produces ketones for fat loss, improved metabolic health, or diabetes management?

If you require therapeutic ketosis, you may want to keep your protein low and add dietary fat to force exogenous ketosis. However, if your goal is fat loss and improved metabolic health, you should prioritise satiety and nutrient density. As a side effect of burning body fat, you may end up in endogenous ketosis.

Protein vs Nutrient Density

Foods with a higher percentage of protein tend to be more nutritious. For whatever reason, the fear of protein has led people to eat more from low satiety.

People negating protein get fewer critical nutrients (like amino acids) from their food and crave more food to compensate. This perpetuates an unhealthy eating cycle that perpetuates a paradox of overeating (energy) while still suffering from nutrient deficiency. As shown in the chart below, up to about 50%, a higher protein percentage correlates with a greater nutrient density.

If you design your diet to achieve high ketone levels as the primary goal, you are also prone to nutrient deficiencies and inherent cravings that result from your body trying to get the protein and nutrients it requires.

What About Protein Powders?

Protein powders can provide bioavailable protein that enables you to top your intake up if you are struggling to get enough. This is a great way for active people to get enough energy and protein to support their activity levels or grow bigger and stronger.

Jose Antonio has led numerous studies where they have tried to overfeed active people with up to 4.4 g protein/kg/day, or five times the recommended daily protein allowance.

The first observation in these studies was that people struggle to eat that much protein, even from processed powders. The second observation was that the participants did not gain weight or body fat despite consuming more calories. This is because the body struggles to convert dietary protein to body fat.

The downside is that protein powders and all the food products that contain them won’t provide you with the same array of nutrients as whole foods. While they provide heaps of amino acids per calorie, they don’t provide a high level of vitamins and minerals as their whole food counterparts.

Perhaps most importantly, powders don’t provide the same satiety as whole-food protein sources. Whey protein is a ‘waste’ product produced during the cheese-making process. Because it is already highly processed, your body doesn’t need to do much work to convert it to usable energy. Thus, dietary-induced thermogenesis is much lower for protein powders than minimally processed forms of protein found in whole foods.

As always, do whatever you can to prioritise nutrient-dense whole foods and use supplementary protein powders as a last resort.

Is Too Much Protein Bad for My Kidneys?

One of the primary functions of your kidneys is to filter your blood. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is a standard test that indicates how well your kidneys work. The eGFR is based on the amount of creatine—the substance produced from the breakdown of protein found in your muscles—in your bloodstream.

Some people become concerned when they see high eGFR levels and think the protein they’re eating is causing kidney dysfunction. However, it shouldn’t be surprising that people eating more protein often carry more muscle than average.

People supplementing with creatine may also see higher creatinine in their bloodstream. Creatine is found in meat and fish and is one of the most well-researched and beneficial supplements for strength, cognitive performance, and even allergies.

We don’t tend to see active bodybuilders getting kidney failure because of their high-protein diets. Instead, it is often the other way around: high-protein diets are often a problem if the kidneys have a pre-existing condition.

If you have late-stage kidney failure and are on dialysis, it’s worth talking to your nephrologist about how much protein they think you should be consuming. But if you don’t already have a nephrologist, then it’s unlikely that ‘too much protein’ will be a concern for your kidneys.

Most people on kidney dialysis have pre-existing elevated blood sugar and blood pressure. According to Dr Ted Naiman, people consuming more protein tend to have larger, higher-functioning kidneys. Eating more protein is akin to beneficial ‘resistance training’ for your kidneys. Similar to how you want to avoid your muscles weakening from disuse, you don’t want your kidneys to atrophy with age.

In a 2018 meta-analysis titled Changes in Kidney Function Do Not Differ between Healthy Adults Consuming Higher- Compared with Lower- or Normal-Protein Diets: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysisby Professor Stuart Phillips, it was found that increased protein intakes do not adversely influence kidney function in healthy adults.

What About ‘Rabbit Starvation’?

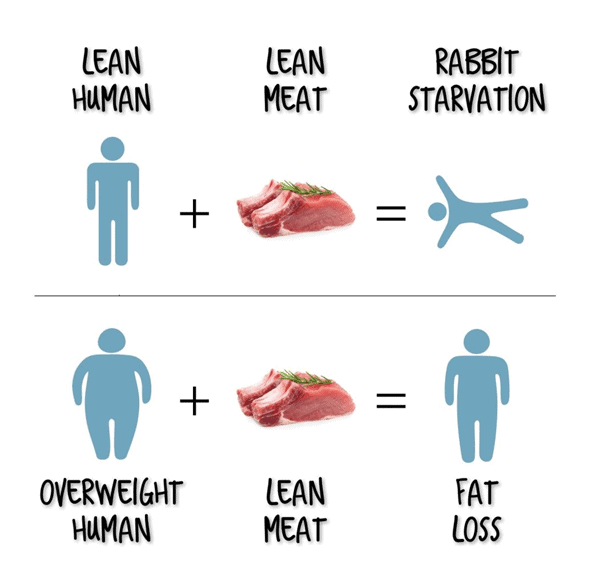

‘Rabbit starvation‘ is a term used to describe what happens to lean and active people when they prioritise lean protein foods and minimise their intake of fat and carbohydrates.

The term originated from active pioneers and explorers who had to live on available game meat, which was often lean. While rabbits are plentiful, they contain meagre amounts of fat.

Therefore, people living on rabbits alone find it difficult to consume enough energy to sustain even low body fat levels. But for most of us with plenty of body fat to burn, this is not an issue! Once we get adequate protein, our appetite for high-protein foods shuts down, and we search for easily-accessible energy from fat and carbs.

If you are getting super lean and only have high-protein foods available to eat, ‘rabbit starvation’ may be an issue for you. But as long as you have a significant amount of body fat to burn, ‘rabbit starvation’ is not something to be concerned about.

Summary

If your only goal is elevated blood ketones, keeping your protein intake low may help. However, prioritising a higher percentage of protein in your diet is a better approach regardless of ketone levels if your goal is fat loss, improved metabolic health, or diabetes reversal.

Get your copy of Big Fat Keto Lies

I hope you’ve enjoyed this excerpt from Big Fat Keto Lies. You can get your copy of the full book here.

What the experts are saying

Get Big Fat Keto Lies!

Get your copy of Big Fat Keto Lies here.

Sample the Other Chapters of Big Fat Keto Lies

- Big Fat Keto Lies: Introduction

- A Brief History of the Low Carb and Keto Movement.

- Keto Lie #1: ‘Optimal ketosis’ is a Goal. More Ketones are Better. The Lie that Started the Keto Movement.

- Keto Lie #2: You Have to be ‘in Ketosis’ to Burn Fat.

- Keto Lie #3: You Should Eat More Fat to Burn More Body Fat.

- Keto Lie #4: Protein Should Be Avoided Due to Gluconeogenesis.

- Keto Lie #5: Fat is a ‘Free Food’ Because it Doesn’t Elicit an Insulin Response.

- Keto Lie #6: Food quality is Not Important. It’s All About Reducing Insulin and Avoiding Carbs.

- Keto Lie #7: Fasting for Longer is Better.

- Keto Lie #8: Insulin Toxicity is Enemy #1.

- Keto Lie #9: Calories Don’t Count.

- Keto Lie #10: Stable Blood Sugars Will Lead to Fat Loss.

- Keto Lie #11: You Should ‘Eat Fat to Satiety’ to Lose Body Fat.

- Keto Lie #12: If in Doubt, Keep Calm and Keto On.

- Resources