Forget everything you thought you knew about carbs and insulin. We’re diving headfirst into the enigmatic “personal fat threshold.”

You’ve probably heard the buzz about carbs triggering insulin, which, in turn, leads to weight gain. But what if we told you it’s not that straightforward? Brace yourself for a deep dive into Dr. Ted Naiman’s revolutionary “insulinographic” and the theory of “adipose-centric” diabesity.

We’ll uncover the secrets behind:

- The carbohydrate-insulin hypothesis of obesity and diabetes,

- The adipose-centric model of diabesity,

- Your personal fat threshold,

- The pros and cons of a low-carb diet,

- Type-2 Diabetes, and

- Personal Fat Threshold.

But that’s not all. We’ll also explore potential solutions and ways to get below your personal fat threshold, including the role of exercise, fasting, protein, and, of course, the magic of a nutrient-dense diet.

So, if you’re ready to unravel the mysteries of insulin, carbs, and your personal fat threshold, keep reading!

- The Carbohydrate-Insulin Hypothesis of Obesity and Diabetes

- The Adipose-Centric Model of Diabesity

- Your Personal Fat Threshold

- The Pros and Cons of a Low-Carb Diet

- Type-2 Diabetes, Personal Fat Threshold and BMI

- So, What’s the Solution?

- What Is My Personal Fat Threshold?

- How to Get Below Your Personal Fat Threshold

- There Is No Substitute for a Nutrient-Dense Diet!

- Summary

- More

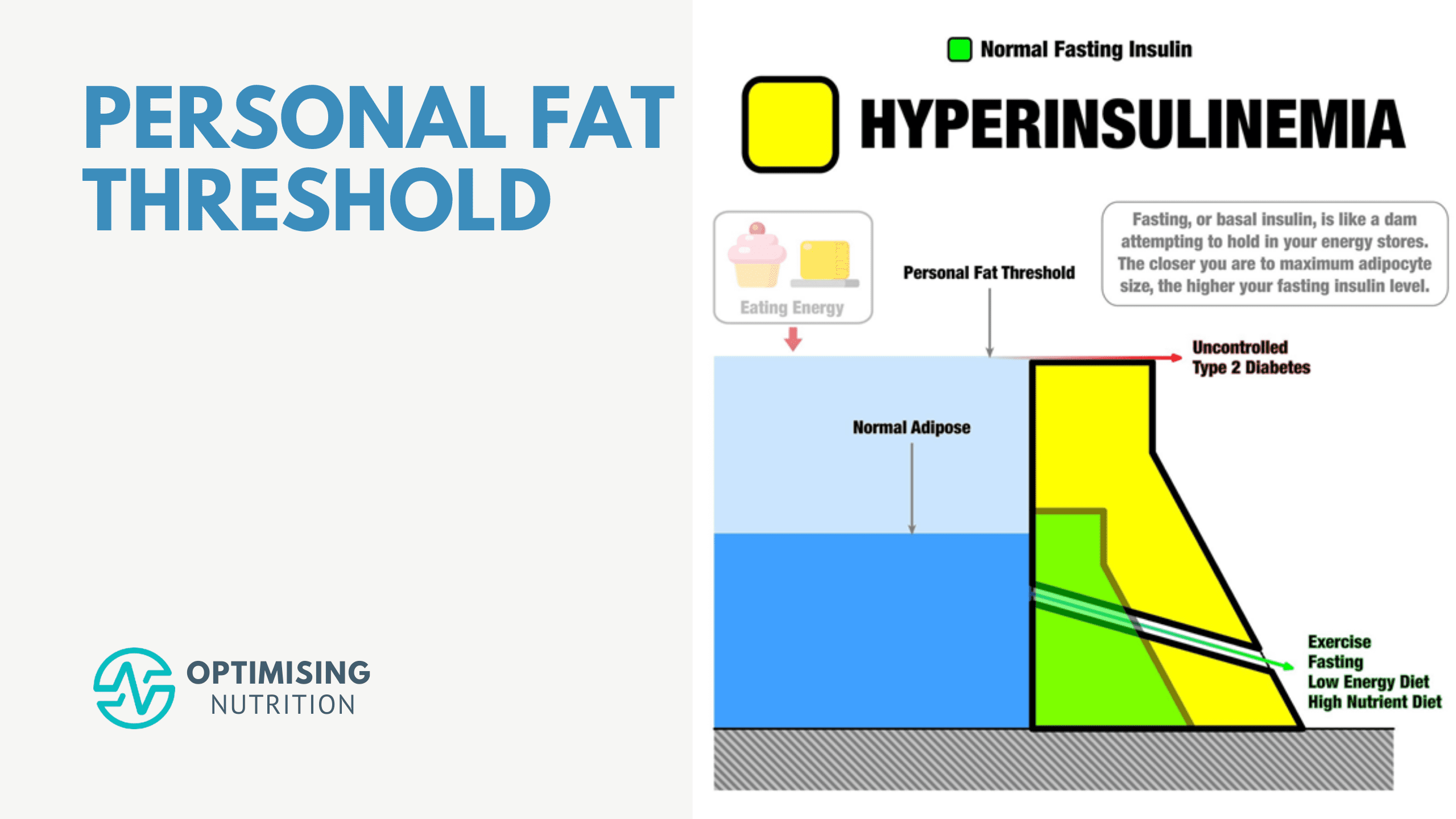

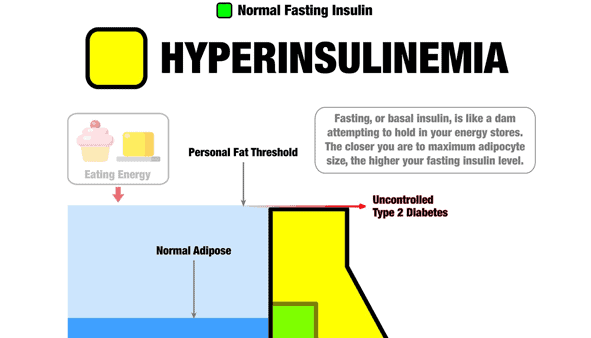

First, I want to clarify that the following graphic isn’t a meme or a graph. Instead, it’s an infographic (or insulinographic) that shows how insulin is an anti-catabolic hormone that works like a dam wall to hold back the flood of stored energy in our bodies.

- If we have healthy body fat levels, we don’t require as much insulin to hold our stored energy in storage (i.e. the smaller green dam wall).

- As we eat and gain more fat, our insulin levels increase to stop our liver from releasing all our stored energy into our bloodstream (i.e. the larger yellow dam wall).

- But ultimately, there’s a limit to the energy we can hold in storage. Eventually, as we get fatter, we reach a point where our pancreas can’t produce enough insulin to stop our liver from releasing excess energy into our bloodstream. Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes results in energy overtopping the ‘dam wall’ and flowing into our bloodstream.

- Hence, the only viable way to lower our insulin and blood sugars is to find a way of eating that allows us to reduce the amount of energy stored in our bodies.

The fascinating thing to note is that, while you are more likely to develop Type 2 Diabetes if you are carrying more fat, there is no specific cut-off where it occurs for everyone. This difference between individuals is known as the personal fat threshold.

To learn more, read on.

The Carbohydrate-Insulin Hypothesis of Obesity and Diabetes

The carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity suggests that people who consume too much refined carbohydrate get fat because carbs increase insulin, and insulin makes your body store energy.

So, based on this insulin-centric theory of obesity, to reverse diabetes, you eat fewer carbohydrates to lose fat and alleviate symptoms of diabetes. Dietary fat gets a free pass because fat doesn’t raise insulin.

The attractive simplicity of the carbohydrate-insulin model has led to people adopting keto, with many books about insulin resistance recommending a ketogenic approach for weight loss.

As you will see, while a lower-carb diet can be helpful for many, it’s not because carbs are the only thing that raises insulin in your body.

The adipose-centric model of diabetes is more helpful in assisting us in understanding what is going on and how to get the results we want.

The Adipose-Centric Model of Diabesity

Imagine your adipose tissue (i.e. the fat on the outside of your body in your bum, belly and cheeks) is like a sponge. When you pour water on it, it will absorb that water. You can squeeze it, and the water will easily come out. The sponge again has plenty of capacity to absorb more water.

But if you drop the sponge into a bucket of water for a while, it will become saturated to the point it can’t hold any more water. There is a limit to how much water the sponge can absorb.

Likewise, there is a limit to how much your fat cells can expand to take in more energy. Eventually, they get full and can’t take any more.

A lean and insulin-sensitive person has adipose tissues that can swell to take on more energy and release it. This is because their insulin levels are low, and insulin flows in and out of storage easily. If you’re insulin-sensitive like these guys, your adipose cells will expand to store energy efficiently when available. For example, an elite cyclist who is lean and has heaps of room in their fat cells to fuel for an upcoming race.

But just like the sponge, our fat stores can only take in so much energy before they become full. Fat cells become ‘insulin resistant’ when they fill up and can’t take on any more energy. This is often accompanied by high insulin levels. At this point, any additional energy that can’t be easily absorbed by your fat cells spills into the bloodstream. Thus, we see elevated glucose, free fatty acids and even higher ketones.

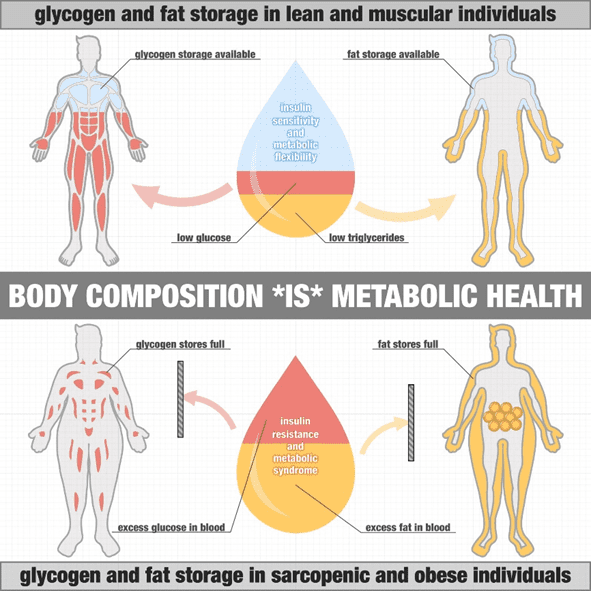

As shown in the image from Dr Ted Naiman, someone who is lean and muscular has plenty of capacity to store the fat and glucose from their diet. In contrast, someone who is obese with little muscle mass has less space to store the glucose, and their fat cells are already full.

With nowhere to go, some of this excess energy is absorbed by vital organs like our heart, liver, and pancreas (which are now more insulin-sensitive than your adipose tissue).

As a result, we see the onset of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), fatty pancreas, heart disease and fatty liver streaks in atherosclerosis and other modern diseases that have become so prevalent due to our nutrient-poor, hyperpalatable, industrial diet.

Your Personal Fat Threshold

To be clear, being obese does not necessarily cause diabetes. Instead, it’s a result of being overfat relative to Your Personal Fat Threshold. Due to their genetics and a range of other factors that we don’t yet fully understand, each person has a unique limit to how much energy they can comfortably hold in their adipose tissue before it overflows and they develop diabetes.

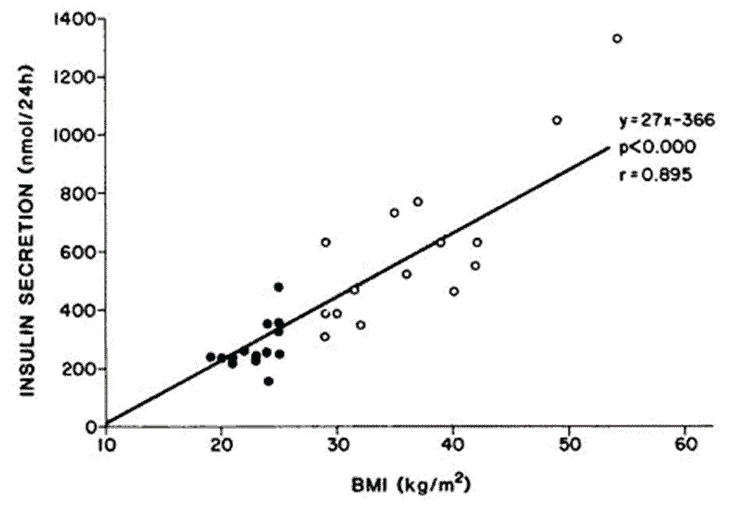

Thus, as observed by Professor Roy Taylor in his landmark 2015 paper, people who are relatively lean find that they can also develop Type 2 Diabetes.

Some people are ‘blessed’ and can store much more energy as fat before becoming insulin-resistant and diabetic. Others find that they can only hold a little bit of energy as fat before it overflows into their organs and bloodstream.

For example, East Asians tend to develop diabetes and metabolic syndrome with a much lower body mass index. In contrast, Pacific Islanders can grow much larger and store a lot more energy on their bodies before they develop diabetes.

You can see how it may have been an advantage in the past for some people to store a lot of energy to survive future times of famine or if they chose to row across an ocean to settle a new island. Today, these people often fatten quickly with a processed diet. They can become very large without developing diabetes, but eventually, they reach their limit and develop metabolic syndrome.

The Pros and Cons of a Low-Carb Diet

A lower-carb diet is a no-brainer for someone looking to stabilise their blood sugars and appetite with Type-1 Diabetes or Type-2 Diabetes.

However, it’s important to make the distinction between a lower-carb diet and a high-fat diet.

Our return on investment diminishes if we only focus on minimising carbs (and even protein, as some do in the pursuit of higher ketones) and ignore the role of dietary fat and fat on our bodies.

High body fat levels and elevated fasting (basal) insulin are the elephant in the room for many people on a low-carb or keto diet. Many people eating a low-carb or ketogenic diet stabilise their blood sugars and improve their HbA1cs but are still obese with high fasting insulin levels.

For more on the important subtleties of basal vs bolus insulin, see:

- The Real Reason Why You’re Insulin Resistant and The Macros to Reverse It

- What Does Insulin Do in Your Body?

The harsh reality is that swapping carbs and protein for more dietary fat doesn’t reverse hyperinsulinemia unless it also reduces the body fat you’re storing!

Many people think that elevated insulin causes obesity. But we’re coming to realise that it’s usually the other way around. It is actually obesity, or at least being over-fat and ‘energy toxic’ relative to Your Personal Fat Threshold, that causes hyperinsulinemia.

Type-2 Diabetes, Personal Fat Threshold and BMI

In 2014, Professors Roy Taylor and Rury Hulman of Newcastle University began to question the widely accepted carb-insulin hypothesis.

They theorised that each individual had their own ‘personal fat threshold (PFT)’. That is, there is a finite amount of fat someone can carry before fat builds up around their liver and pancreas.

At this point, they go from being metabolically healthy obese to having Type-2 Diabetes, prediabetes, and insulin resistance. But if someone lost enough weight and fell below their PFT, their metabolic conditions would fall into ‘remission’, and vice versa.

In their published 2015 study, Normal weight individuals who develop type 2 diabetes: the personal fat threshold, they tested their theory. They put subjects on a low-calorie diet and monitored how their bodies responded throughout the year-long study duration.

All study participants started at different body weights. In just one week, subjects showed lowered insulin levels and improved blood sugar. After one year on the low-calorie diet, many participants lost weight and regained the full function of their pancreas.

They found that the beta cells (cells in the pancreas that produce insulin) of people with Type-2 Diabetes hadn’t been destroyed but had instead ‘thrown in the towel’ and shut down with the overwhelming amount of energy to metabolise.

All subjects who fell into remission for their diabetes lost weight, but every participant regained their metabolic function at a different weight. Thus, we see that everyone has their own unique PFT. This understanding explains why there are people of varying body weights and body mass indexes (BMIs) who experience T2D.

The chart below shows the distribution of BMIs from a 2019 study carried out by Taylor et al. The frequency of BMIs shown in blue was before subjects gained weight and were free of diabetes.

The distribution shown in red shows the onset of metabolic syndrome after participants had exceeded their PFT and metabolic syndrome had developed. The dotted line in Figure C represents each individual’s unique PFT. You can see that each individual has a unique PFT where they trip over into having metabolic syndrome.

In the follow-up one year later, those who regained the weight had relapsed with their Type-2 Diabetes. However, those who kept the weight off and stayed below their PFT did not.

While different people diagnosed with Type-2 Diabetes have different BMIs, a general cluster of unhealthy BMIs coincide with diabetes.

Obesity is a leading risk factor for diabetes, but not all obese people are diagnosed with it (and some healthy-weighted people are).

So, What’s the Solution?

The bottom line is that insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome are not simply a result of eating too many carbs.

Instead, it’s a bit more complex (but still simple) than that, and there are a few more things to factor into the cause and the plan of action.

But if insulin and carbs aren’t to blame for our obesity and diabetes, what can we do? Is it back to just eating less and exercising more?

Well, sort of. But not exactly.

The key to the whole puzzle comes down to lowering Your Personal Fat Threshold.

What Is My Personal Fat Threshold?

By now, you’re probably wondering how you can calculate Your Personal Fat Threshold so you can restrict your calories, lose just the right amount of weight, and kick your metabolic syndrome.

While body weight and other biometrics can be easy to calculate, calculating your personal fat threshold is not simple.

First, to determine if you are above your personal fat threshold, you check your waking glucose. If it’s over 100 mg/dL or 5.6 mmol/L, then you’re above your personal fat threshold.

You can use a simple blood glucose monitor (or a continuous glucose monitor if you already have one) as a fuel gauge to determine whether or not you need to eat and refuel again.

Over time, as you unload the extra energy you have onboard, your waking glucose and insulin sensitivity will improve.

While you cannot step on a scale or sit in a machine to get a definitive BMI or body weight that will tell you Your Personal Fat Threshold, you can reduce your baseline blood glucose levels using a glucometer to regain your metabolic health just as we do in DDF.

Once your waking blood glucose is below 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L), you can rest assured you’re under Your Personal Fat Threshold and can decrease your risk of diseases associated with energy toxicity and metabolic syndrome.

Once you find the weight and body composition that allows you to achieve healthy waking glucose, you can keep this in mind as a reference for the future.

How to Get Below Your Personal Fat Threshold

As shown in the bottom right corner of Ted’s insulinographic, there are several things we can do to lower our dam wall, including:

- exercise,

- fasting,

- an energy-restricted diet,

- a nutrient-dense diet, and

- a high-protein percentage intake.

Exercise

The 80% diet-20% exercise theory seems to have some merit.

While a nutrient-dense diet is foundational for good metabolic health, exercise is an adjunct we can use to improve insulin sensitivity and burn off fat and sugar without using insulin.

Resistance training, lower-intensity activity (zone 2), and spurts of more intense activity are incredibly effective.

Check out Macros Masterclass FAQ #7 Optimising Your Exercise for more tips on exercise.

Fasting

Not eating for a while is another excellent way to reduce your insulin.

Once you use up the glycogen stored in your liver and muscles, your body lowers your insulin levels and turns to your adipose tissue to allow more stored body fat to flow over the dam into the system.

For some people, the problem with fasting comes when they quickly overdo it, when it’s time to refeed. When I was fasting regularly to lose some extra fat, I found I would permit myself to eat more than I otherwise would have. The foods I chose to eat were also much less nutrient-dense and more energy-dense than usual.

Despite the saint-like adherence to the self-deprivation I endured for days on end, I found that I didn’t lose much weight over the long term. Instead, I seemed to eat back my deficit in the end! My wife Monica would say, ‘I don’t think this extended fasting thing is working for you! Why don’t you try eating a little less each day?’

Rather than falling for the fasting for longer trap, you can use your glucose to guide when and what you eat to ensure you achieve a negative energy balance over the long term without pushing it so hard that you rebound and make poorer food choices that will undo your hard work.

For more details on this approach, check out Data-Driven Fasting: How to Lose Weight and Reverse Type 2 Diabetes Without Tracking Your Food.

A Higher Protein Percentage (Protein %)

Increasing protein can help build your metabolically active lean muscle mass, allowing you to burn more calories at rest. In addition, because of the thermic effect of food, you could also increase the amount of energy (calories) you were burning when converting it into usable energy (ATP).

Increasing your protein percentage does not simply mean adding more protein to whatever you’re currently eating. Instead, it’s a matter of scaling back your intake of dietary fats and carbs and increasing your intake of protein and fibre to allow your body to use its fat stores to fuel itself.

This leads to a greater protein percentage (protein %), or per cent of total calories from protein. A higher protein % is linked to improved satiety, which can help you lose weight over time.

In our four-week Macros Masterclass, we walk participants through this very process so they can find the protein percentage most optimal for their goals.

Low-Energy Diet

As Ted’s insulinographic also highlights, a low-energy-dense diet is another way to lower your basal insulin levels.

You can achieve this by focusing on more foods with a lower energy density and highly satiating and making it harder to overeat, as we outline in our Secrets to a Nutrient-Dense Protein-Sparing Modified Fast article. This ensures you’re using your body fat stores for fuel, which decreases your insulin levels as you lose weight.

This is why some people who switch to a whole-food, plant-based (WFPB) diet can reduce their insulin requirements and reverse their diabetes. As long as they stick to whole foods, they cannot ingest enough energy to maintain their weight, and their insulin decreases.

For more details, see Low Energy Density Foods and Recipes: Will They Help You Feel Full with Fewer Calories?

There Is No Substitute for a Nutrient-Dense Diet!

Maximising nutrient density is my favourite ‘hack’ because it addresses all the following factors:

- It provides adequate protein. If you eat foods containing the vitamins, minerals, and essential fatty acids you require, you will obtain plenty of protein. Protein is the most satiating macronutrient if we’re analysing it on a calorie-for-calorie basis. There is a lot of confusion around protein. But if you eat foods containing adequate amounts of vitamins, minerals, and essential fatty acids, you’ll get plenty of protein. Conversely, actively avoiding protein can lead to nutrient deficiencies. Whether your approach is increasing nutrient density, targeting the most satiating macronutrients, or focusing on foods that naturally provide you with greater satiety, you arrive at the same point.

- It has a low energy density. A nutrient-dense diet relies on low-energy-dense whole foods with lower levels of refined carbs and processed fats that are hard to overeat.

- It’s minimally processed. Quantifying nutrient density is a foolproof way to ensure that the foods you’re eating contain the micronutrients you need rather than hyper-palatable flavourings and colours that Frankenfoods use to mimic like they are suitable for you (but they’re not). These minimally processed foods are also satiating without being hyper-palatable, so they are self-limiting.

- It prevents cravings. Avoiding diabetes, controlling body weight, and lowering insulin and blood glucose seem to boil down to the same thing: getting the nutrients you need without too much energy or eating a nutrient-dense diet. Focusing on nutrient-dense foods improves satiety, which helps you dodge cravings that drive your appetite unnecessarily.

Summary

- The carb-insulin model is the most well-known theory behind diabetes and diabetes management and is centred around lowering carbohydrate intake to reduce insulin production.

- The amount of fasting insulin we have is proportional to the amount of food we consume, our body fat levels, and Your Personal Fat Threshold.

- The adipose-centric model states that someone’s fat cells will expand and contract based on their insulin sensitivity.

- The Personal Fat Threshold Theory is the new and improved theory behind hyperinsulinemia, and it states that we will experience T2D and metabolic syndrome when we surpass a fat threshold unique to us. Here, we begin accumulating fat around our liver and pancreas, contributing to metabolic dysfunction.

- Insulin is primarily an anti-catabolic hormone that allows us to keep our energy in storage. Lowering your body fat levels is the key to decreasing insulin levels, which helps you reduce your bolus insulin. This is explained via the Personal Fat Threshold Theory.

- Micronutrients are the missing link that most people overlook to increase satiety and T2D management and lower their PFT.

- Eating a nutrient-dense diet, exercising, fasting, and increasing your protein % are some of the best ways to lower Your Personal Fat Threshold and fasting insulin.

More

- What Is Insulin Resistance (and How to Reverse It)?

- How to Reverse Type 2 Diabetes and Optimise Your Blood Sugar

- What Does Insulin Do in Your Body?

- How Much Weight Should I Lose Per Week for Sustainable Weight Loss?

- Unlock Your Metabolic Potential with Data-Driven Fasting

- How to Really Reverse Your Insulin Resistance

- What Does Insulin Do in Your Body?

- Macros Masterclass

- Data-Driven Fasting

Perfectly understood Marty ✌

“A relevant example of this is Jimmy Moore’s recent high protein experiment where he reduced his fasting insulin from 14.2 to a very respectable 8.8 mIU/mL.”

Not sure, but wasn’t the insulin 18 after the experiment? That’s what I heard on podcast …

Am I wrong?

The insulin reading of 18 was taken on the Monday when the lab was open, but the experiment finished on Sunday 8 April and then he refed on F-bombs and his normal diet. So the insulin reading after five days of the high protein is the only one that is representative of high protein or any level of energy restriction. The jump from 5 to 18 is a good indication of how he body responds in the longer term to higher levels of energy.

Thanks for your answer.

Where did you find this information about 8.8 for fasting insulin on day 5? I couldn’t find it…

In the podcast when he talks about his insulin response on day 5 to high protein. It jumped from 8.8 to 20 after high protein (although 20 is still pretty good for a post meal reading).

Yeah, totally agree!

Thank you so much.

Just got a chance to list to the podcast. It seems that all of Jimmy’s insulin resistance markers when down and he noted that he lost weight when eating high protein (which has not been able to do on a high fat diet). His issue was low blood sugar after eating. What seemed interesting was the blood sugar levels after eating were similar to what he had during his 7 day fast.

Carbohydrates cause cancer, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, liver disease and dementia.

Do you have a reference for that belief?

Interested in your take on this study which shows hyperinsulinemia precedes diabetes and it is not correlated with obesity.

http://annals.org/aim/article-abstract/704330/slow-glucose-removal-rate-hyperinsulinemia-precede-development-type-ii-diabetes

Thank you for this article. It’s been challenging for me to grasp the adipose-centric model of diabesity, but this article has helped and in fact explains some real life observations for me. I lost 70 pounds on a commercial PSMF program before conceiving my first child. After that pregnancy I started more of a traditional Keto diet with high fat and moderate protein. My weight was stable at about 50 pounds down from my highest, but I never reached my pre-pregnancy weight and I noticed that I seemed to be gaining size around my midsection (despite no change in weight). I’ve now had a second child and am planning to do another PSMF once I’m done breastfeeding. If this is successful I will certainly have anecdotal support for this theory. Thank you for helping me to understand.

Congratulations on your success. You may be interested in this post on the PSMF approach. https://optimisingnutrition.com/2017/06/17/psmf/

PSMF is essentially what is prescribed after weight loss surgery. People keep saying weight loss surgery is forced fasting but at most it is intermittent fasting with emphasis on protein first. I am 5 years post sleeve and working back from regain by going back to the basics of the plan of no snacking and protein first. I do not regret the surgery. It has taught me how to eat properly and my experience was very smooth with an excellent surgeon with proper diet and support post surgery.

So PSMF works very well especially with IF. Of course it helps to have a stomach 80% smaller and with less grehlin the first several months to keep appetite down. But even without surgery it should be very effective (and less expensive!)

Which study is the “one year randomized controlled trial isocaloric isocarbohydrate low carb”? A google search comes up empty.

Why is PSMF simply not calorie restriction, which has been shown to fail basically 100% of the time (not to mention cause many deleterious effects, eg, ghrelin goes up, BMR goes down)? I can’t understand that.

a hardcore PSMF is hard to maintain long term because it ends up being extreme calorie restriction. but any diet that works long term provides greater satiety. protein % is the most powerful lever in satiety. adequate dietary protein preserves LBM and helps to maintain BMR.

But… Doesn’t fasting still work in the end?

Yeah. If you don’t overdo the refeed, which is possible if you’re choosing lower protein more energy dense foods.

Marty, This is auch a lovely article. Can’t thank you enough. Could this be one of the reasons why your fasting glucose reads higher than Post prandial? I have an HbA1c: 5.7, Fasting 110, PP 95, Fasting insulin 21. I have been trying Keto and strength training, My fasting glucose had dropped to 84 when I was on strict keto and fasting insulin has dropped from 24 to 21.

Thank you so much Marty! Such continuing clarity! What an amazing change from the years of being alone in the blame ridden wilderness! So appreciate your work and the generosity w which you share. â•ï¸

Excellent.

Thanks Wyatt!

Thanks: amazing article/post.

I especially enjoyed the part regarding fat/keto and fasting insulin.

I wasn’t aware of that, like that JM had a 14.2 value.(after all these years).

What a shame that there aren’t any studies where the read extends over the 120th minute mark. How is that even possible?

This article was so enlightening for me. Thank you! I have been keto for 2+ years and my weight loss was okay at first but I have barely lost anything the last several months and I still have so much weight to lose. I could not figure out what the issue was as I kept zeroing in on my macros and getting my carbs really low (10 grams). I had a really bad experience on a low-fat diet years ago so I thought more fat was nourishing and helpful. Your article explained WHY my weight loss is so little while my weight is still so high. Started PSMF 5 days ago and have dropped 5 pounds. Feeling very excited with this information and a solution!

The metabolic pathway for dietary fat does not depend on insulin for storage so how can it raise basal insulin levels? Are you saying an excess of energy from too much dietary fat creates a calorie surplus that increase basal insulin levels?

Yes. The more fat we have to hold in storage the harder our pancreas needs to work to produce basal insulin.

for me I tried every diet in teh book (I have high fat threshold apparently) keto started me out but I wasnt really losing that much weight, or feeling better, (well maybe some better) but I listend to a doctor about addictions (i was not planning on fasting I get to hungry) well I was trying to follow the insulin index diet, finding out that milk has variable numbers and what the doctor said about addictions decided to stop drinking milk (cheese doesnt give me problems I can eat a slice inmy salad and be okay) and realized that some meats have some affect on insulin but it has high satiety for me. one guy was saying fasting helps you regain your true hunger, but I ended up falling into intermitten fast because I was losing my appetite over time. and my body did it on it’s own. when I got h ungry I realized that guy was right.that hunger was different then the nawing feeling in my stomach and feeling. anyway I can actually stick to a diet now and be satiated if I eat the right foods. and avoid the wrong ones (that triggor to much insulin).

you need to watch this video from Professor Roger Unger. His theory and experimental data matched perfectly to yours.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VjQkqFSdDOc&ab_channel=KarolinskaInstitutet

yes. this is a brilliant lecture. he has a really profound understanding of how everything actually works. this was a real inspiration for me when it came out back in the day.

Many thanks for sharing. This was most interesting and I subscribe to the PFT model. Being South Asian and being more genetically predisposed to Type 2 diabetes has made me super feaful of getting diabetes. I walk 5 miles a day, do H.I.I.T cycling workout 2x week and 3x week brutal pushup workout for the resistance piece. I do consume a calorie controlled higher protein diet and it is mostly nutrient and fibre rich but far from perfect due to my sweet tooth addiction and bad habit of including junk food into the mix. A few months ago I tried a keto diet with intermittent diet, I lost lots of weight and had the best blood markers ever, but regrettably I also lost a ton of muscle mass in the process and couldn’t sustain such a restrictivr way of eating even when squeezing in Keto Desserts. I saw an interview from Roy Taylor in which he stated that based on his research average weight loss to have diabetes go in remission if you were obese was approximately 33 lbs if you were obese and if lean then approximately 15% of your total body weight or 20-25 lbs. I have lost approimately 50 lbs over 3 years and currently cannot even fit into skinny outdated clothes I have in my closet from years ago. I still have a BMI in the really high end that makes me wonder if my PFT may still be in the danger zone. I bought a blood glucose monitor when I did keto but was unable to use it as no matter how many different ways I poked my finger and strategies I used I coukd never get enough of a blood sample for the meter to even register a reading. I would love to confirm if my waking glucose is below 100 mg/dL or 5.6 mmol/ to put my mind at ease one way or other and take further mitigating actions as necessary. For this, I will need to try and convince my doctor to prescribe a CGM so I can get an accurate reading. That will be a challenge as I know my doctor won’t likely do it as unless my A1C results come back in the prediabetic or diabetic range by which time it may be too late 🙁