Will the debate around eating plants vs. animals ever end?

Ever since Cain and Abel, people have been zealous about their chosen way of eating.

But when religious beliefs, ethical conviction, environmental sustainability and big business align around food, they are a force to be reckoned with.

Most people agree that we should avoid highly processed, nutrient-poor foods.

Still, if you listen to the latest “nutrition documentaries” and other people talking loudly about a vegan diet, you would think EVERYTHING wrong with our food system is simply due to eating animals.

If you were a little cynical, you might wonder if all these films are designed to make people fearful of animal-based foods. Once they believe this, they will buy more products from Big Food grown by highly subsidised and profitable industrial agricultural practices.

- Who can we trust for nutritional information?

- What are the Optimal Nutrient Intakes?

- Nutrients in all food

- The most nutrient-dense foods

- Nutrient-dense example

- Carnivore

- Carnivore example

- Nutrient-dense animal-based foods

- Nutrient-dense carnivore example

- What about vegan foods?

- “Healthy” vegan example

- Junk food “plant-based” example

- Nutrient-dense vegan

- Comparison of approaches

- The bottom line

- More

Who can we trust for nutritional information?

Unfortunately, it’s impossible to draw clear conclusions from epidemiological data.

Every study or conversion experience seems to come from the background of a heavily processed nutrient-poor western diet.

When people switch to [insert preferred way of eating here] diet, their health miraculously improves!

“Why isn’t everyone eating this way?” they say.

However, I find it hard to believe that these improvements are due to reducing plants/carbs/fat/animal-based foods when the common factor in all of the dietary approaches that work is the exclusion of heavily processed hyperpalatable junk food.

Then we have the “healthy user bias“. People that care enough about their health to conscientiously implement a particular dietary approach are typically looking after their health in a multitude of other ways and thus confound the data.

Fortunately, our detailed analysis of forty thousand days of food logging from more than a thousand people provides useful insight into the parameters of nutrition to enable us to better manage our food quantity and quality.

The amount we eat is important, not only to optimise our metabolic health (obesity, diabetes, heart disease, etc.) and our economy (spiralling health costs and reduced productivity), it’s also important to understand how our dietary choices affect our use of limited planetary resources. Very few of us seem to be able to balance the calories in vs calories out equation successfully.

But perhaps more important than our health and appearance, understanding how we can eat to regenerate our bodies and our environment is critical to enable us to support a healthy population, now and in the future.

What are the Optimal Nutrient Intakes?

Our data analysis suggests that getting enough nutrients without excess energy (i.e. nutrient density) is the most crucial factor in nutrition and optimising our health.

As you will see in this article, food quality and quantity are intimately related. But sadly, the discussion about nutrition rarely involves nutrients.

While there is some debate around the Recommended Dietary Intakes for the various nutrients, the DRIs are only the minimum amount of the essential nutrients required to prevent diseases of deficiency in the short term.

Alarmingly, many people are not meeting these minimum target nutrient intakes! But if we’re going to debate which foods are optimal for health, wouldn’t it make sense to talk about the nutrient intake levels that align with optimal health?

According to Bruce Ames, if your diet contains fewer nutrients, you will “triage” the available nutrients and prioritise short term survival. However, if you provide your body with more than the minimum, it will be able to optimise for longevity and healthy ageing.

This is why we defined Optimal Nutrient Intakes (ONIs). While the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) define the minimum intake of essential nutrients to avoid diseases of deficiency, the ONIs define the optimal amount achievable with food that aligns with increased satiety and helps us to maintain a healthy appetite and body composition.

We can then use the ONIs to compare which foods and dietary approaches provide the nutrients that we need to thrive, not just survive.

So, what nutrients do we need to prioritise and which foods contain more of them?

Nutrients in all food

The nutrient fingerprint chart below shows the essential nutrients as a proportion of the Optimal Nutrient Intakes across the eight thousand foods in the USDA food database. At the bottom of the chart, we see that we can easily achieve optimal intakes of phosphorus, sodium and iron, while at the top of the chart we see that we need to work harder to get enough omega 3, vitamin A, vitamin E and vitamin B1 from our modern food system.

The most nutrient-dense foods

Rather than focusing on the foods that contain more of a single nutrient, we can use the ONIs to identify the nutrient-dense foods and nutrient-dense meals that contain more of the nutrients we are not getting enough of.

This next chart shows the nutrient fingerprint of the highest-ranking 25% of foods in the USDA database when we prioritise the harder to find micronutrients (i.e. calcium, magnesium, vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B3 and omega 3).

Though we haven’t prioritised any amino acids, nutrient-dense foods tend to contain a lot more protein. Nutrient-dense foods also tend to be more satiating (meaning they are much harder to overeat and will leave you feeling full for longer).

While you probably won’t consume as much energy from these foods, you will still get plenty of the nutrients you need to thrive for the long term.

Conversely, when we consume a nutrient-poor diet, our appetite ramps up to get the nutrients we need, even if we have to consume a lot more energy in the process.

Nutrient-dense example

To show how this could look in practice, the table below shows a selection of 2000 calories worth of nutrient-dense foods designed to hit most of the ONIs.

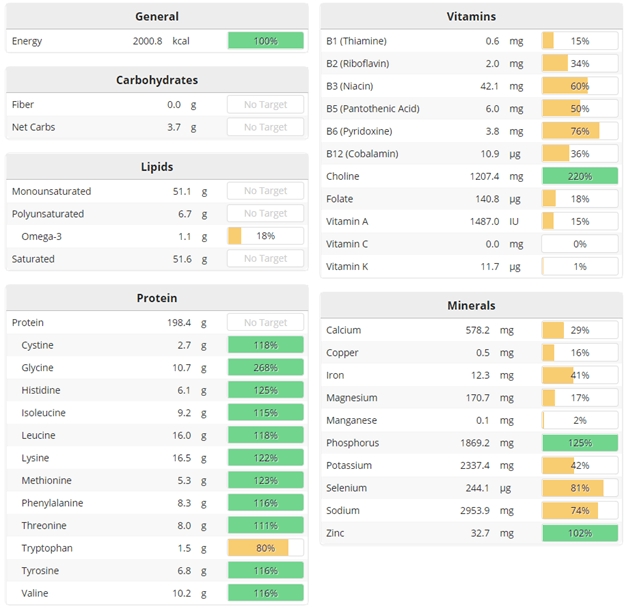

The Cronometer screenshot below shows the micronutrient profile of these foods compared to the Optimal Nutrient Intake for 2000 calories.

Protein tends to come with foods that contain plenty of vitamins, minerals and essential fats. While there is no added fat (e.g. oil, cream, butter, etc.), we still get about 40% of calories from fat.

Although we’re getting more than half the weight of the food from bulky nutrient-dense non-starchy vegetables, the non-fibre carbohydrate is still less than 40 grams.

If you looked at all these nutrient-dense foods on a plate, many people would call it “plant based” because it has more plant based foods by weight and volume. However, if you knew that 85% of the calories come from the meat and seafood foods you probably aren’t going to call it “plant based”.

Can you see how defining your diet as “plant based” is virtually useless if your goal is to identify nutritious food that is good for you.

Carnivore

Before we look at plant-based foods, let’s look at the nutrient profile if we went carnivore.

The chart below shows the nutrient profile of all animal foods and seafood in the USDA database. While we get plenty of protein (50% of calories are from protein), there are several nutrients (such as vitamin K1, C, E, A, omega 3, folate, B1, magnesium and calcium) at the top of the chart that are harder to obtain in adequate quantities.

Carnivore example

The analysis below shows a typical carnivorous diet with steak, eggs and cheese. Although this is only about 2 lbs of food per day, it will still be fairly satiating due to the higher protein content.

The Cronometer screen grab below shows the nutrients provided by these foods as a proportion of the Optimal Nutrient Intakes. While we get plenty of protein, choline, phosphorus and zinc there are a number of gaps in the nutrient profile (i.e. manganese, vitamin C, B1, K1 and copper).

A carnivorous diet will provide plenty of protein for satiety and remove many foods that people experience autoimmune responses to. For many people, a carnivorous approach can be a great elimination diet for a period, after which more nutrient-dense foods can be introduced to see how you tolerate them.

We have created a book of nutrient-dense recipes containing meat for people who like eating this way.

The nutrient fingerprint of the recipes from the meat book is shown below.

Nutrient-dense animal-based foods

We can also focus on the foods that contain more of the harder to find nutrients on a carnivorous diet. The nutrient fingerprint chart below shows that we still struggle to get adequate amounts of several nutrients.

Nutrient-dense carnivore example

The Cronometer analysis shows some of the more nutritious animal-based foods.

This ends up being about 1.1 kg (or 2.5 lbs) of food. While we cover off on most of the essential nutrients, we still struggle to get the Optimal Nutrient Intake of calcium, B1, C, K1, magnesium and potassium (which tend to be more plentiful in non-starchy vegetables).

What about vegan foods?

The fingerprint chart below shows the nutrients we would get if we removed all animal, dairy and seafood from the USDA database to provide a “plant-based” diet without any regard for food quality or nutrient density. Unfortunately, simply avoiding animal-based foods doesn’t give us a very good nutrient profile.

But what is a “plant-based diet” anyway? If you listen to the nutrition documentaries out there, you would think that a plant based diet is one that excludes ALL animal products. I’ve also seen other people define a plant based diet as one that has more plant than animal products, but is that by weight or calories?

Simply defining your diet as “plant-based” does not exclude the processed junk food made of refined grains and cheap seed oils that are nutrient-poor and easy to overconsume. In fact, the combination of sugar, vegetable oils and refined starch (with flavourings and colours) is essentially the formula for modern junk food.

As shown in the chart below (based on data from the USDA Economic Research Service) it’s the “plant-based” added “vegetable oils” along with cereal grains and flour that have increased to dominate our food system over the past fifty years (note: vegetables, dairy and meat have remained relatively unchanged).

It’s also important to be aware that “plant-based foods” from industrial agriculture are heavily reliant on synthetic fertilisers which are made by fixing nitrogen in the air to hydrogen from methane which is extracted from coal seams.

The explosion of easy energy that has been injected into our food system from natural gas over the last fifty years is far from sustainable over the long term! Sooner or later we will need to find a way to reduce our reliance on fossil fuel inputs into our food system.

If we exclude vegetables, fruits and nuts (i.e. that few people actually eat significant amounts of) we get an even poorer nutrient profile.

“Healthy” vegan example

The nutrient analysis below shows how the nutrients in 2000 calories of a fairly healthy plant-based diet might look. We have not included any hyperpalatable junk food or added oils, but there also aren’t any vegetables. This ends up being about 1.1 kg (or 2 lb) of food.

From a macronutrient perspective, we get a lower proportion of protein and more carbohydrates than the carnivore or omnivore approaches. There are a large number of essential nutrients that are underrepresented, particularly B12, A, omega 3 and K1.

Junk food “plant-based” example

As an extreme example, the analysis below shows how 2000 calories of junk food could look with some chips, white bread, doughnuts, Coke and margarine (note: no animal products, but 100% plant-based). This is only 400 g (i.e. less than a pound) of solid food and is not going to keep you full for long.

The macronutrient profile is a mix of carbs and fat, with only 5% protein.

The micronutrient profile is inferior across the board. We get plenty of poly and monounsaturated fats, but not a lot of nutrients.

While this is an extreme example, it’s unfortunately how more and more people are eating these days and still very much qualifies as “plant-based”.

Sadly, if all you do is encourage people to avoid animal products, there is a high probability people will turn to the cheapest, tastiest and most energy-dense option.

It’s also not too far off the EAT Lancet “plant-based” recommendations that have apparently been developed with the goal of “saving the planet”.

EAT Lancet also happens to be sponsored by the most prominent industrial agriculture, food, biotech, pharmaceutical and chemical companies in the world (who likely have some financial interest in you going “plant-based” without any consideration of the nutritional content of your diet).

Nutrient-dense vegan

All these plant-based food documentaries would be less concerning if they encouraged people to prioritise nutrient-dense vegetables.

When we focus on the nutrient-dense plant-based foods, we get about twice as much protein, a lower energy density and a much better nutrient profile compared to the average of all of the available plant-based foods. However, we still struggle to get enough omega 3 (which usually comes from seafood) and B12 (which comes mainly from animal products).

The analysis below shows what a nutrient-dense plant-based diet with lots of veggies (to provide vitamins) and nuts (which contain the minerals that are also found in fish and meat) could look like. This ends up being more than two kilos (or four and a half pounds) of food. This will require a significantly larger investment of time, preparation and eating than most people are used to.

The protein is relatively low, but we do get a lot more fat from the nuts (which can provide minerals on a plant-based diet).

The micronutrient profile is a lot better than the plant-based approaches analysed above. However, there are still several gaps in the nutrient profile. It’s also worth noting that some of the nutrients, such as vitamin A and omega 3, will be less bioavailable compared to their preformed versions in animal-based foods.

We understand that some, for a range of reasons, prefer to eat a plant-based diet. So to help people avoid the pitfalls of a highly processed “plant-based” diet, we created a book of dense nutrient plant-based recipes.

The nutrient fingerprint of these recipes is shown below. These are THE most nutritious plant-based recipes available.

For those who prefer a vegetarian diet, we also created a book of vegetarian recipes.

As you can see from the nutrient fingerprint chart below, these recipes have a higher nutrient density (e.g. more B12, omega 3, zinc, etc.) than the purely plant-based recipes.

For more details on our series of recipe books (i.e. macro and micronutrient profile), check out this article.

Comparison of approaches

The table below shows a summary of the analysis in terms of protein, fat+net carbs, energy density (i.e. ED in kg/2000 calories), protein:energy ratio and the nutrient density score.

| approach | protein | fat+net carb | ED | P:E ratio | ND score |

| nutrient-dense omnivore | 46% | 44% | 1.5 | 1.05 | 97% |

| nutrient-dense carnivore | 62% | 38% | 1.4 | 1.63 | 81% |

| nutrient-dense plant-based | 23% | 62% | 1.2 | 0.37 | 73% |

| carnivore (all foods) | 50% | 50% | 1.0 | 1.00 | 69% |

| average all foods | 26% | 57% | 0.7 | 0.38 | 57% |

| plant-based (all foods) | 12% | 80% | 0.8 | 0.15 | 45% |

A “plant-based diet” without regard for nutrients also has the lowest nutrient density score. You will need to consume four or five times as many calories to get the same amount of protein as some of the other approaches.

Would “going plant-based” make us all fatter and be bad for the planet?

Our satiety analysis of forty thousand days of data from more than a thousand Optimisers allows us to quantify how the food affects our likelihood of eating more.

One of the significant findings of our analysis was that the strongest predictor of satiety is the percentage of protein. A higher percentage of protein tends to align with a lower energy intake.

The general population average intake and the “plant-based” approach (without consideration of nutrient density) both sit at about 12% protein which aligns with the poorest satiety outcome!

It’s not simply a matter of eating MORE protein, but rather targeting a higher percentage of energy from protein. As shown in the chart below, simply eating more protein without regard for the extra energy from fat and carbs will simply lead to a greater calorie intake. You probably know intuitively that the whopper with double cheese on white bread bun and fries on the side isn’t going to help you see your abs any time soon.

The protein dilution of our food system seems to be strongly correlated with our tendency to consume more calories.

As well as helping you to build and repair your muscles and organs, amino acids play a critical role as precursors to your neurotransmitters. Your reptilian instincts and cravings work to make sure you are getting enough to allow your brain to function optimally.

As we increase the energy from non-fibre carbohydrates and fat, we tend to consume more calories. At one extreme we have a hyperpalatable junk food diet with a mix of carbs and fat with low protein, while at the other extreme we have a protein-sparing modified fast style diet that many bodybuilders use to get super lean without experiencing too much hunger.

Experiments in rats show that they tend to experience hyperphagia (i.e. uncontrollable appetite) when they are exposed to foods that are a combination of fat+non-fibre carb (i.e. obesogenic rat chow).

While there’s plenty of debate about the optimal amount of protein if your waist-to-height ratio is greater than 0.5, you’ll likely benefit by reducing your intake of easy energy from fat and non-fibre carbs (which will in turn increase your protein %).

The obesity epidemic has been fuelled by an increase in energy from both fat and carbohydrates, made possible by synthetic fertilisers, modern food processing and large scale farming practices. Since the 1960s, we have been producing more than a thousand extra calories per person per day, mainly from plant-based agriculture (i.e. vegetable oils and cereal grains).

In addition to % protein, nutrient density is another parameter that has a significant effect on our calorie consumption. The chart below from our satiety analysis shows that a higher Optimal Nutrient Score tends to align with a lower energy intake. Once we get enough nutrients, our cravings for more food tends to decrease.

Given our understanding of the relationship between these parameters and satiety, we can estimate our likelihood of eating more or less with these various approaches.

The chart below shows the % protein with the various approaches overlaid. The average protein content of all foods in the USDA database is 26% which corresponds to a calorie intake of around 110% of our basal metabolic rate (BMR). At the lower extreme, we have the plant-based foods which correspond with an energy intake of 22% above our BMR. At the high protein extreme, we have the very lean high protein nutrient dense carnivore approach which corresponds with an energy intake 37% below our BMR.

We can do the same for the Optimal Nutrient Score as shown in the chart below. The plant-based approach with no consideration of nutrient density has the highest energy intake while all of the nutrient-dense approaches correspond with a much lower energy intake.

The table below shows the calculated intake as a proportion of our BMR based on the percentage of protein and nutrient density. The right-hand column shows the number of calories likely to be consumed by someone with a basal metabolic rate of 2000 calories per day with each of these approaches.

| approach | % BMR (protein) | % BMR (ONI score) | average % BMR | estimated calories |

| nutrient-dense carnivore | 63% | 70% | 67% | 1,330 |

| nutrient-dense omnivore | 85% | 70% | 78% | 1,550 |

| animal-based (all foods) | 78% | 83% | 81% | 1,620 |

| nutrient-dense plant-based | 113% | 73% | 93% | 1,850 |

| average all foods | 115% | 104% | 110% | 2,190 |

| plant-based (all foods) | 122% | 111% | 116% | 2,330 |

This chart shows the estimated calorie intake graphically.

The “downside” of the nutrient-dense animal-based approach is that not many people will be able to sustain a diet of 62% protein without losing too much weight. Once you get enough protein, your appetite sends you in search of easy energy from fat+carbs.

An omnivorous diet with a focus on nutrient density with enough energy to maintain a healthy body composition is likely a reasonable approach for most people who want to stay lean and healthy.

A focus on nutrient-dense foods and meals that contain adequate protein will enable you to need less energy and potentially have a lower impact on the planet, while also optimising your health. Take a moment to imagine what would happen to our health and the planet if we could modify our food system, so we all ate a thousand fewer calories a day.

Dialling back the refined energy (mainly from plant-based sources such as grains, sugar and vegetable oils) would effectively turn back the clock on the obesity epidemic and our excess calorie consumption that is depleting our limited natural resources.

The bottom line

Simply going ” ‘plant-based”, without regard for nutrient density, will lead to a less nutritious diet with less protein and fewer essential nutrients that will tend to lead to a higher calorie intake.

The current trend towards a “plant-based” diet without any consideration of food quality is highly likely to simply reinforce and perpetuate the nutritional paradigm that has made us obese and sick over the past 50 years!