In the ever-evolving world of nutrition, the battle between high-protein and high-fat diets rages on.

But the ideal balance between these two macronutrients isn’t one-size-fits-all. Your protein-to-fat ratio should align with your unique goals, whether it’s managing blood sugar, losing weight, gaining muscle, boosting performance, or maintaining a healthy weight.

In this exploration, we’ll dive into the data to help you find your perfect protein-fat balance, a process that’s guided thousands of Optimisers in our Macros Masterclass.

Join us as we uncover the mysteries of carbohydrate intake, explore the power of protein, and decode the role of fat in your diet.

By the end, you’ll have a clear roadmap to determine whether high-protein or high-fat aligns with your health and wellness objectives, all while making informed dietary choices tailored to your needs.

- What is Your Ideal Carbohydrate Intake?

- How Much Protein Do You Need?

- Finding Your Ideal Fat Intake

- Should Keto be High-Fat or High-Protein?

- Is Protein or Fat Better for Weight Gain?

- Protein vs Fat for Weight Loss

- Is High-Protein or High-Fat More Nutrient-Dense?

- Why Do I Get Hungry When I Eat More Protein and Less Fat?

- What’s The Minimum Protein Intake to Lose Weight?

- Summary

- More

What is Your Ideal Carbohydrate Intake?

Most of the time, people debating high-protein vs high-fat are in the low-carb, keto, or carnivore communities. Thus, their carbs are already pretty low.

But before we dive into protein vs fat, let’s consider the other macronutrient: carbohydrate.

As the chart below from our satiety analysis shows, moving from about 45% non-fibre carbohydrates to 10 to 20% non-fibre carbohydrates align with a significant 23% reduction in energy intake!

We tend to consume more calories when our diet consists of a hyper-palatable conglomerate of fat and carbs. This mix of fat and carbs is rare in nature, and only appears to help us gain weight (i.e., in autumn before winter or when a baby needs to fatten up).

However, the fat+carb combo is typical in modern ultra-processed foods engineered to make us eat and buy more of them. But aside from being super tasty, these foods provide lots of calories and little in the way of nutrients and satiety.

You may not need to reduce your carbohydrate intake to the ‘optimal’ carbohydrate range (i.e., 10-20% carbs), especially if you are more active. However, moving in that direction will increase satiety, particularly if your blood sugars tend to be elevated after meals.

For more details on finding your ideal carbohydrate intake, see Carbohydrates – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR).

In our Macros Masterclass and Data-Driven Fasting Challenge, we encourage our Optimisers to dial back their intake of processed carbohydrates if their blood glucose rises by more than 30 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) after meals. This indicates you’re overfilling your glucose fuel tank and eating more carbs than your body requires.

Significant blood sugar rises can lead to rapid decreases not long after. This condition is known as reactive hypoglycaemia, which can contribute to increased cravings and a tendency to make less-than-optimal food choices when your glucose is lower than what you would generally be comfortable with.

For more details on dialling in your blood sugars, see What Are Normal, Healthy, Non-Diabetic Blood Sugar Levels?

How Much Protein Do You Need?

Next, we’ll look at protein.

We all require enough protein to build and repair our muscles and organs, make neurotransmitters and hormones, detoxify, and perform many other bodily functions.

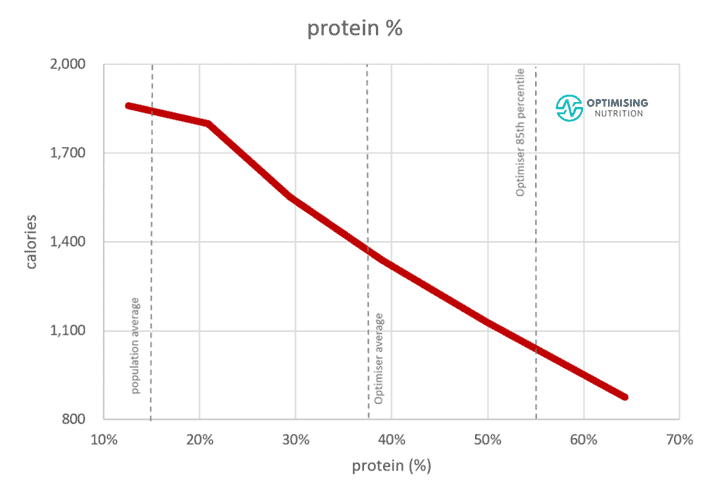

We know from our satiety analysis that protein is the most satiating macronutrient. Thus, increasing the protein % of your diet—or the percentage of total calories from protein—aligns with a lower calorie intake.

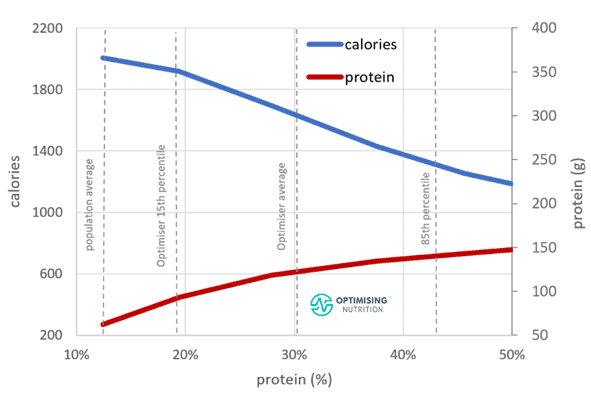

As shown in the chart below, people who consume a diet with the highest percentage of calories from protein tend to consume 60% fewer calories!

If your goal is to increase satiety so you can eat less and lose weight, it can be helpful to dial up your protein %. But to do this, you don’t necessarily need to eat more protein; instead, it’s more beneficial to reduce energy from carbs and fat and prioritise protein.

Our analysis shows a continuous benefit to eating a more significant percentage of our total calories from protein. The 85th percentile protein intake for our Optimisers lies around 44%. Only 15% of people achieve more than 44% protein.

But rather than swinging from one extreme to another, we recommend progressively moving in this direction until you begin seeing your desired results (e.g., 0.5 to 1% weight loss per week). In our Macros Masterclass, we walk our Optimisers through this process in a progressive and structured manner.

While protein is the most satiating macro calorie-for-calorie, pushing too hard too early can lead to excessive hunger after a few days. People often quickly fall off the wagon and find themselves in a rebound binge.

Finding Your Ideal Fat Intake

Lastly, we come to fat.

If you’ve dialled back your carbs to stabilise your blood sugars, your fat intake will likely be on the higher side. This is fine, especially in the early stages of a lower-carb diet.

However, fat is the most energy-dense macronutrient. It tends to provide little overall in the way of micronutrients. Hence, many people find they must dial back fat in the long term to keep improving their body composition.

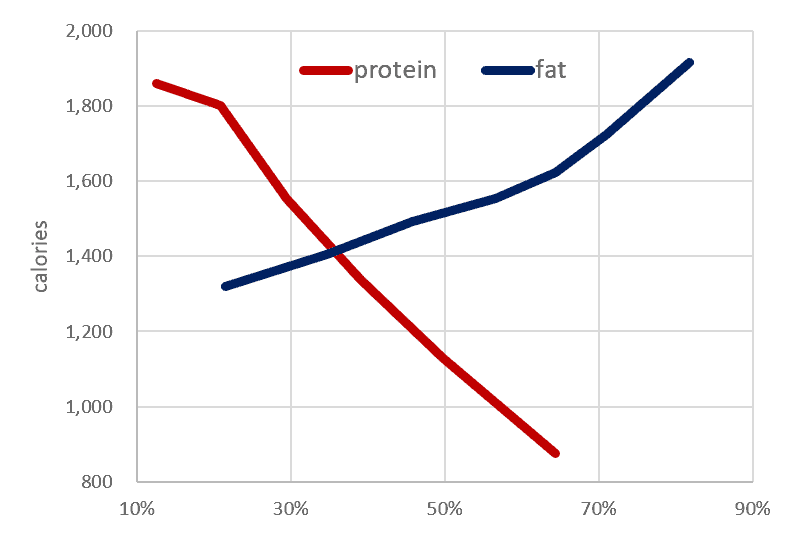

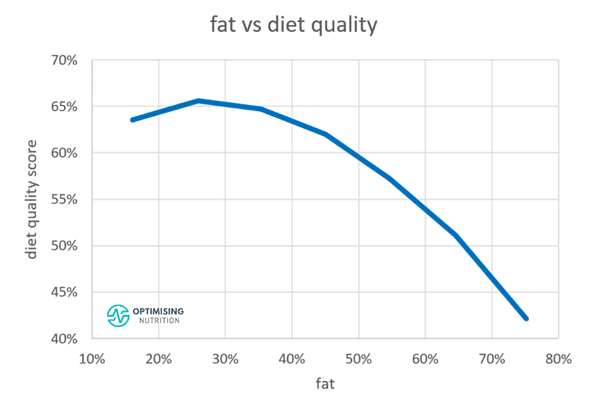

Fat is a great slow-burning energy source, but you may need to reduce the fat in your diet to lose body fat. As the chart below shows, people who consume more energy from fat consume more calories.

Once you have dialled in your carbs and protein, you can easily ‘use fat as a lever’ to reduce the extra energy in your diet. You can start by cutting back on fatty dressings. Later, if necessary, you can seek out leaner cuts of meat and seafood.

For more on finding your ideal fat intake, see Fat – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR).

Should Keto be High-Fat or High-Protein?

Over the past five years, the keto and low-carb communities have shifted their focus from high-fat to higher-protein, leaving many confused about what they should target.

So, which is correct?

The answer depends on what your context and goals.

‘Keto’ means a lot of things to a lot of people. For those looking to achieve therapeutic levels of ketosis to manage a condition like dementia, cancer, Parkinson’s, or Alzheimer’s, they must consume 80-90% of their calories from fat to produce enough exogenous ketones (ketones from dietary fat). More protein might hinder your efforts if your primary goal is elevated ketones.

In contrast, someone eating a low-carb, higher-protein diet for weight loss and diabetes management does not require super high ketone levels to reach their goals. Hence, someone may be able to consume more protein and still yield their desired results.

But if calories are low and they are dipping into their fat stores, they may still produce endogenous ketones—or ketones from their body fat—too.

As you can see, both of these approaches can be ’ketogenic’. The one right for you depends on where you want the ketones to come from.

- The higher-fat, lower-protein approach will be more likely to produce ketones from dietary fat (i.e., exogenous ketosis). Unfortunately, it also has a higher chance of potentially adding fat to your body.

- Meanwhile, a higher-protein, lower-fat diet may produce fewer blood ketones, but those ketones will be from your body fat rather than dietary fat. Hence, you will produce more endogenous ketones.

Is Protein or Fat Better for Weight Gain?

To simplify things, you can think of weight loss and weight gain as a scale. The more weight you want to gain, the more fat and carbs you want to consume. If you want to lose weight, focusing on protein and fibre is better while limiting energy from fat and carbs.

Protein is the most thermogenic macronutrient. In other words, we burn the most energy (calories), turning it into usable fuel (ATP). Interestingly, we can burn as much as 25-35% energy from protein during this process! In comparison, we only lose around 3-10% of energy from fats and carbs turning it into usable fuel.

Additionally, the amino acids that makeup protein are the most satiating nutrients, so it might be hard to eat more if you only focus on protein. High-carb and high-fat foods contain fewer amino acids, which are critical for satiety. Hence, eating a higher percentage of protein will make it hard to consume more calories. Conversely, consuming less protein will make it easier to consume more energy.

So, if you want to lose weight, focusing on more fat and carbs might take you in the wrong direction!

But don’t worry: if your goal is weight gain, adding tasty fat is a great way to get more energy AND protein if you choose the right nutrient-dense, high-fat whole foods. These options tend to come with plenty of protein, so you won’t have to worry about getting enough protein to maintain muscle mass.

Protein vs Fat for Weight Loss

The following chart shows the satiety response to protein vs fat. When it comes down to it, there is really no contest. A higher protein % aligns with a lower overall calorie intake, while more fat aligns with a higher calorie intake.

But it’s important to find the right balance for you. In our Macros Masterclass, we guide our Optimisers through tracking their typical diet for a week before progressively dialling in their protein, fat, and carbs to align with their context and goals.

If you’re lean, active, and want to eat more to support your activity, you’ll want to consume more fat, more carbs, or more fat and/or carbs. The balance of fat vs carbs will depend on your preferences, the activity you’re performing, and the duration you’re doing it for.

People who perform lower intensity, more extended duration activity often find they have more stable energy when they fuel with more fat. However, if you’re doing a lot of explosive activity, you may benefit from some more carbs before, after or during your activity to prevent your blood sugars from dropping too low.

But, if you’re on the other side of the spectrum and you’ve got body fat that you want to lose, it’ll be better to aim for a little less fat, fewer carbs, and a higher protein %. This will increase your satiety and allow you to feel full on fewer calories so you can burn off your body fat and excess stored glucose for fuel.

Is High-Protein or High-Fat More Nutrient-Dense?

Next, we’ll look at how going high-protein vs high-fat influences one’s Diet Quality Score or the nutrient density of their diet.

If you remember from our satiety and nutrient density articles, increasing your nutrient density—or the number of micronutrients you’re consuming per calorie—is critical for satiety and feeling full on fewer calories.

In the first chart, we can see that a higher protein % aligns with better diet quality up until around 50% of calories come from protein. This means that you’ll not only be getting plenty of amino acids but also more vitamins, minerals, and essential fatty acids like omega-3s as your protein % increases.

Protein tends to come packaged with fat. Because omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids are essential, they often come with higher protein foods. But similar to refined carbohydrates, consuming fats beyond the minimum of what is required dilutes the nutrient density of your diet and only provides extra energy.

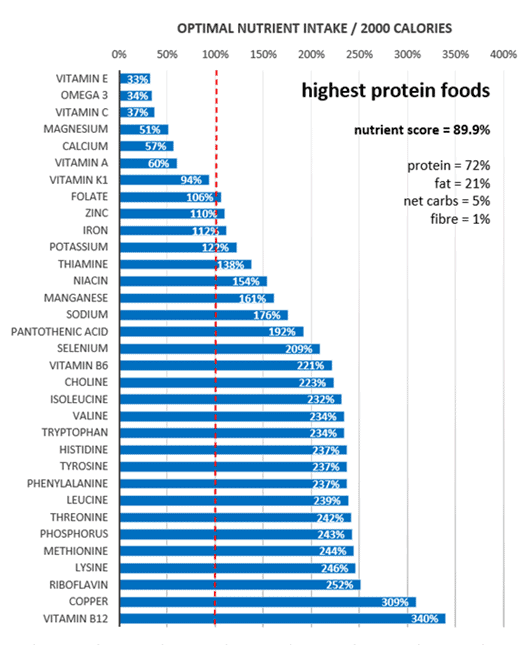

To illustrate how a higher protein % can affect nutrient density, the chart below shows the micronutrient fingerprint of the highest protein high-protein foods. While we get plenty of amino acids and other essential nutrients, we can see towards the top that we wouldn’t get much vitamin E, omega-3, magnesium, or calcium.

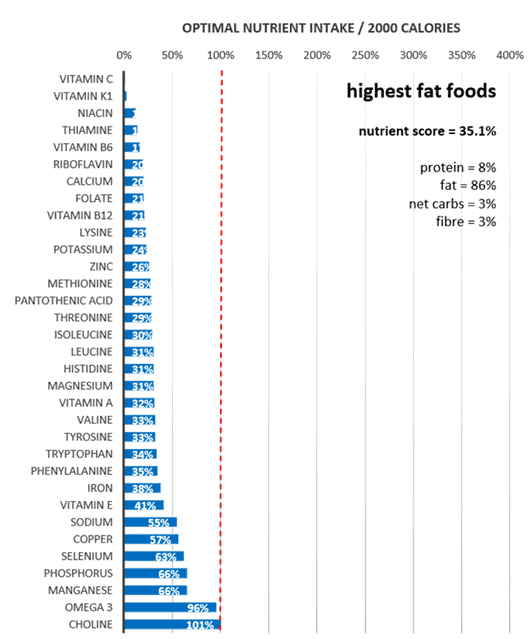

In contrast, the following chart compares the micronutrient profile of the highest-fat foods. At the bottom, we can see plenty of omega-3s and choline, but many other nutrients shown at the top are severely lacking. Overall, the highest-fat foods are much less nutritious than the highest-protein foods.

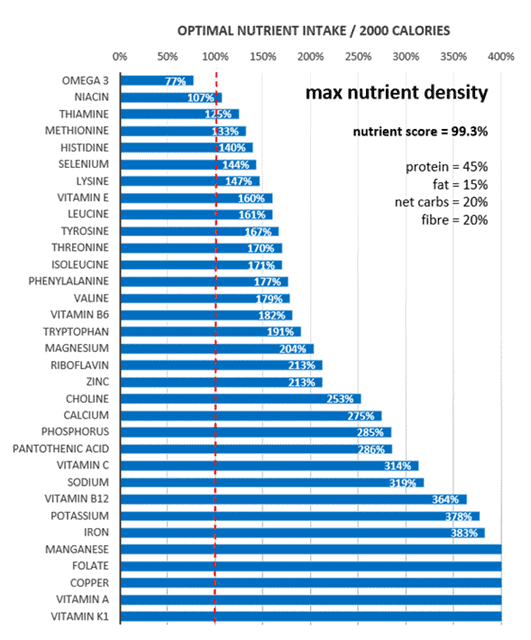

Rather than thinking in terms of high-fat vs high-protein extremes, our analysis has shown we get a much better micronutrient profile if we focus on getting enough of all the essential nutrients (nutrient density).

Consuming more nutrient-dense foods increases your protein % naturally and supplies you with many other essential nutrients so you can give your body what it needs, smash your cravings, and give your body what it needs to thrive.

As shown in the micronutrient fingerprint chart below, foods with the highest nutrient density have plenty of protein. They are more nutritious than the highest protein foods and way more nutritious than the highest fat foods.

If you’re curious about what nutrients you’re getting—or which you aren’t—you can take our Free 7-Day Nutrient Tracking Challenge to get a detailed micronutrient fingerprint showing your nutrient gaps.

Why Do I Get Hungry When I Eat More Protein and Less Fat?

Many people find they get hungry when they rapidly dial up the protein % of their diet, concluding that protein is less satiating than fat. Because you can burn calories turning protein into usable fuel, it can literally increase your energy demand.

People also tend to consume fewer calories when they eat more protein because it is so satiating, so they may not be eating adequate energy. However, judging this is impossible unless you’re accurately tracking your food. Fat may feel more satiating, but that may be because you’re taking in a LOT more calories from the fat.

For more detail on finding your ideal protein intake, see Protein – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR).

What’s The Minimum Protein Intake to Lose Weight?

The official Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) for protein is 0.75 grams per kg of body weight. This is the minimum intake estimated to prevent diseases related to protein deficiency (e.g., kwashiorkor) in most people. In other words, it is by no means optimal for satiety or overall health.

However, given the lowest % protein intake aligns with the most significant calorie intake, you may not want to aim for this minimum.

On the other end of the spectrum, protein advocates and bodybuilders recommend 1 g/lb body weight (2.2 g/kg body weight). However, this can be hard to hit if you’re just starting, especially if you’re coming from a traditional high-carb, high-fat standard western diet and your goal is to eat less and lose weight.

As shown in the chart below, increasing protein % only aligns with a moderate increase in protein in absolute terms. Hence you may not need to eat a LOT more protein if your goal is optimising your metabolic health; you may only need to increase the amount of protein you’re consuming while scaling back your intake of fat and carbs.

No matter your goals, there is a limit to how much protein your body can use. More protein is not necessarily better. Any excess beyond what your body requires for basic functioning is converted to energy. Higher-protein foods are often packaged with more fat, so it can be easy to exceed your energy budget.

We tend to find that 1.4 g/kg lean body mass (LBM) is a more realistic starting point for most people that can spare them the pitfalls of ‘overdoing it’.

The table below shows what 1.4 g/kg LBM would look like for you based on your height and gender.

| Height (cm) | Height (in) | Female Protein (g) | Male Protein (g) |

| 150 | 59 | 56 | 76 |

| 155 | 61 | 60 | 81 |

| 160 | 63 | 64 | 86 |

| 165 | 65 | 68 | 92 |

| 170 | 67 | 72 | 98 |

| 175 | 69 | 77 | 103 |

| 180 | 71 | 81 | 109 |

| 185 | 73 | 86 | 116 |

| 190 | 75 | 90 | 122 |

| 195 | 77 | 95 | 128 |

| 200 | 79 | 100 | 135 |

| 205 | 81 | 105 | 142 |

| 210 | 83 | 110 | 149 |

In our Data-Driven Fasting 30-Day Challenge, we recommend participants ensure they’re eating at least this much protein before restricting. To check your current intake, it’s pretty easy to track what you’re currently eating for a few days in Cronometer.

If you’re not meeting this minimum amount, you should add some higher-protein foods and meals to ensure you meet this minimum intake before trying to lose weight. Otherwise, building muscle—which fuels your metabolism—and staying full enough to avoid binges may be challenging. For some inspiration, see:

- Highest-Satiety Index Meals and Recipes

- High-Satiety Index Foods: Which Ones Will Keep You Full With Fewer Calories?

You can also use our Macro Calculator to give you a running start on your protein, fat, carb, and overall calorie targets. Later, if you want some more guidance, you can take our Macros Masterclass.

Summary

- The ideal balance of protein vs fat depends on your goals.

- If you require therapeutic levels of ketones, you should opt for a higher-fat diet with lower protein.

- If you require more energy to fuel activity or gain weight, you may need more fat and carbs relative to protein and more energy overall.

- If your goal is weight loss or managing a metabolic condition, you should prioritise protein with less energy from fat so your body can use stored body fat.

- And if you’re trying to manage your weight, you should consume adequate protein and fibre alongside enough fat and carbs to match your energy output.

- Rather than swinging from one extreme to another or defining your diet by extreme terms like ‘high’ or ‘low,’ it’s ideal to understand how you currently eat before tweaking it and moving in any direction.