Did you know you can use glucose as a fuel gauge to precisely guide when and what to eat to guide your weight loss without counting calories?

We designed Data-Driven Fasting, building on my learnings from living with two people with Type 1 Diabetes (my wife and son). But over the past three years running three dozen Data Driven Fasting Challenges, we’ve learned even more about how anyone can use their blood glucose to make more intelligent food choices.

This article will show you, with pictures, how to manage any scenario you might encounter to give your body precisely what it needs when it needs it.

- How to Use the Insights from Your Glucose

- Your Personalised Glucose Trigger

- Find Your Carbohydrate Tolerance

- Fat Keeps Your Glucose Elevated for Longer

- Carbs + Fat Together

- Protein Forward Nutrient Dense Meals

- Protein at Breakfast

- Light Exercise

- Intense Exercise

- Rescue Carbohydrates

- Intra-Day Carb Cycling

- Optimal Eating Patterns for Weight Loss

- Next Steps

How to Use the Insights from Your Glucose

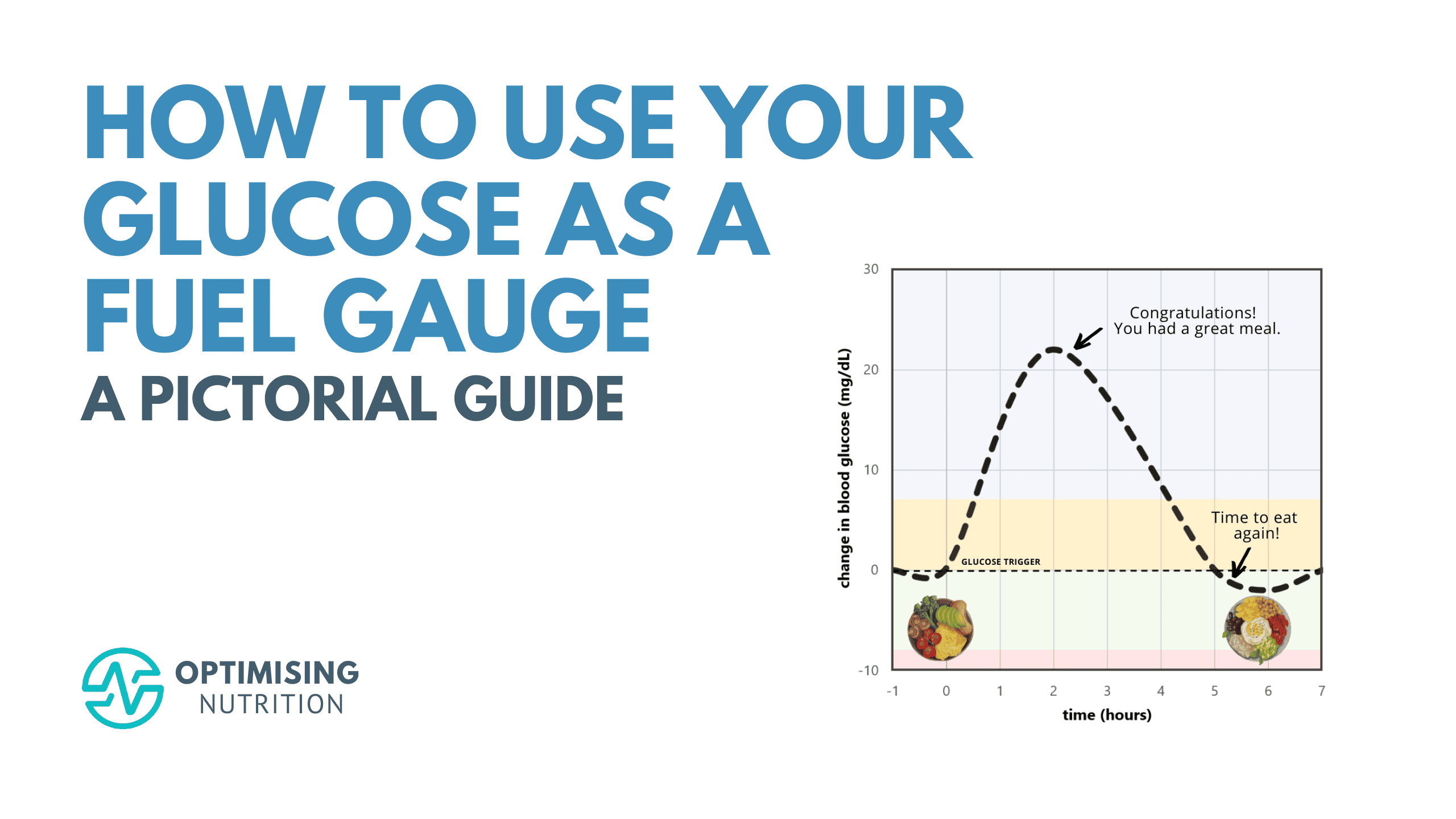

The premise of Data-Driven Fasting is that if your glucose is above normal for you, there’s no need to eat — you have plenty of fuel mobilised in your bloodstream, ready to be used.

But if you are hungry and your glucose is lower than normal, it’s time to eat. However, you don’t want to push your fuel gauge to empty because this leads to intense hunger and poorer food choices.

Your simple glucose meter is as close as it gets to having an instantaneous fuel gauge for your metabolism.

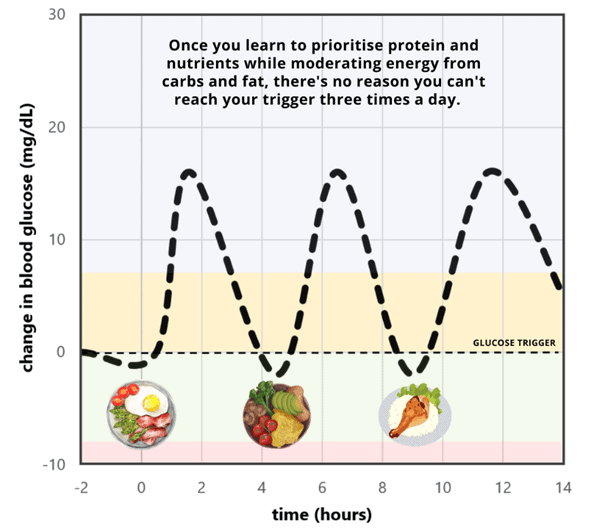

The image below shows the ideal scenario. After you eat, your glucose rises for a few hours before returning to your normal glucose level.

Once your glucose is below your normal premeal level, you’re tapping into your stored fat and glucose. So, if you’re hungry, it’s time to eat again.

By paying attention to your blood glucose, you can ensure you give your body precisely what it needs when it needs it.

Your Personalised Glucose Trigger

You’ll notice a dotted line on these charts that denotes your personalised glucose trigger. Your glucose trigger is simply the average of your glucose before you eat during the three-day baselining period.

In the Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, participants use the DDF App to calculate their initial trigger. The DDF App slowly lowers your trigger to ensure you are drawing down on the stored glucose in your body so you can access your stored body fat.

Find Your Carbohydrate Tolerance

When they start measuring their glucose, most people focus on the rise in glucose after they eat. While this is a great place to start, it’s only the beginning.

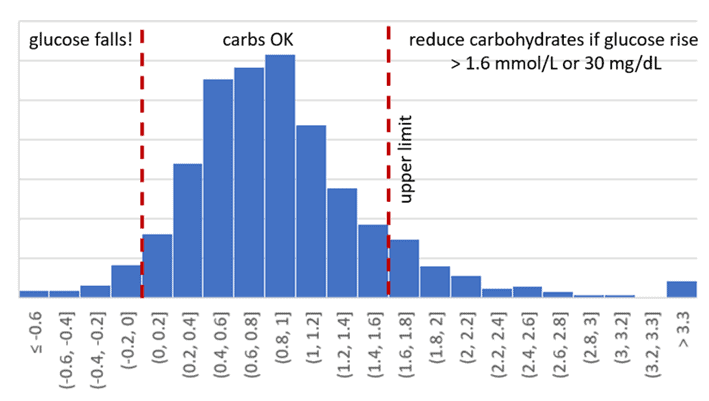

As shown below, fast-acting carbohydrates raise your glucose quickly. Elevated glucose is not optimal, particularly over the long term. But in the short term, it is the crash after the rise that is the real problem.

When glucose falls quickly, we get hungrier sooner and make poorer food choices. Very low glucose is an emergency signal – our lizard brain takes over! For more details, see Reactive Hypoglycaemia: Symptoms, Causes & Dietary Solutions.

There’s nothing wrong with carbohydrates. They’re simply a source of fast-acting energy that your body will use before it uses the fat in your diet and the stored fat on your body.

But if your glucose rises by more than 30 mg/dL above your personalised glucose trigger, you likely had more carbs than your body needed — you overfilled your glucose fuel tank. For more details, see Oxidative Priority: The Key to Unlocking Your Body Fat Stores.

People who are lean and metabolically healthy will tend to see a smaller rise in glucose after they eat. This is because they have plenty of room in their liver and muscles to store the energy from the carbs they just ate. But people who already have plenty of fat and glucose stored in their bodies don’t have that luxury. So, reducing your carbs is often helpful if your glucose rises above the upper limit line.

Over the first week or so of our Data-Driven Fasting Challenge, participants identify the foods and meals that raise their glucose the most and progressively eliminate them from their repertoire based on the feedback from their glucose after they eat.

People can safely trust their appetite once their glucose oscillates in the normal healthy range — hunger is no longer an emergency. As you’ll see in the next section, the goal is not to achieve flatline blood glucose levels. Instead, some oscillation in glucose is part of your normal satiety and fullness signals.

If you’re wondering what a normal glucose rise looks like, the chart below shows the range of rise in glucose we see after eating from the four thousand or so people who have done Data-Driven fasting, with an average rise in glucose after eating is 16 mg/dL (or 0.9 mmol/L). Most people from the keto or fasting background find they’re not overdoing carbs. See What Are Normal, Healthy, Non-Diabetic Blood Glucose Levels? for more detail.

Fat Keeps Your Glucose Elevated for Longer

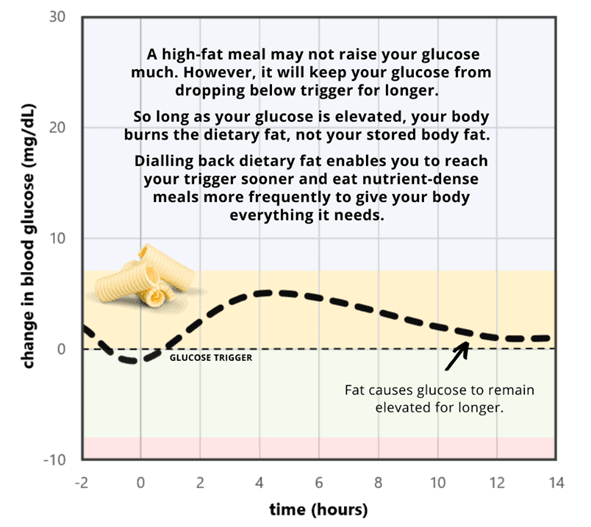

Many people find it tempting to simply swap carbs for fat to stabilise their glucose, but that’s not necessarily optimal.

While fat doesn’t raise glucose or insulin much in the short term, dietary fat will keep your glucose elevated longer. Unfortunately, you’ll have to wait longer to reach your trigger and eat again.

People with Type 1 Diabetes know they need more insulin after a high-fat meal, and their glucose will stay elevated for longer. Similarly, participants in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges find that when they dial back their dietary fat, they can reach their trigger and eat again sooner.

For more details, see:

- Making Sense of the Food Insulin Index,

- How To Use a Continuous Glucose Monitor for weight loss (and why your CGM Could Be Making You Fat), and

- Glycemic Index vs Glucose Score: Best Way to Lower Your Blood Sugar Levels After Eating.

Carbs + Fat Together

While we need some energy from carbohydrates and/or fat, we often get into trouble consuming foods combining carbs and fat (e.g., pizza, creamy pasta, cookies, croissants etc.). The carb + fat combo is the basic formula for ultra-processed, hyperpalatable, hyper-profitable food.

Foods that combine carbs and fat fill the fat and glucose fuel tanks in our bodies simultaneously. So not only do we eat more of these foods before we feel satiated, but they also raise our glucose and keep it elevated for much longer.

In our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, people quickly find that consuming these meals too often means they can’t reach their trigger for many hours or even days. As a result, it takes a long time to drain their glucose and fat fuel tanks.

It may be tempting to ‘hack’ your glucose and add fat to your carbs to blunt the rise in glucose after eating (also known as clothing your carbs). But this is the dumbest thing you can do for satiety, weight loss and metabolic health!

For more details, see:

- How to Make the Most of Your Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) Data, and

- Glucose Revolution by Jessie Inchauspe (the Glucose Goddess): Review.

Protein Forward Nutrient Dense Meals

Foods with a higher percentage of protein contain less energy from fat and carbs while still providing the nutrients that we require.

You don’t need to eat more protein to lose fat and preserve your lean mass, but protein-forward meals will ensure your body gets the nutrients it needs to feel energised and maintain your lean mass while using the fat and glucose stored in it.

Data-Driven Fasting doesn’t require you to wait until you reach your trigger every time you eat. But if you’re hungry and your glucose is staying elevated, opting for a higher-protein, nutrient-dense snack or smaller protein-focused meal to tide you over until your glucose drops is often helpful.

This resembles a Protein Sparing Modified Fast when your glucose is elevated. The chart below shows some higher protein foods in terms of protein per serving vs protein %. For more inspiration, check out our list of higher-protein % foods here.

Rather than just thinking in terms of protein %, it can be more effective to prioritise foods and meals with a higher nutrient density, as shown in the chart below. For more options, you can check out the nutrient-dense food lists here and our Maximum Nutrient Density NutriBooster recipes,

Protein at Breakfast

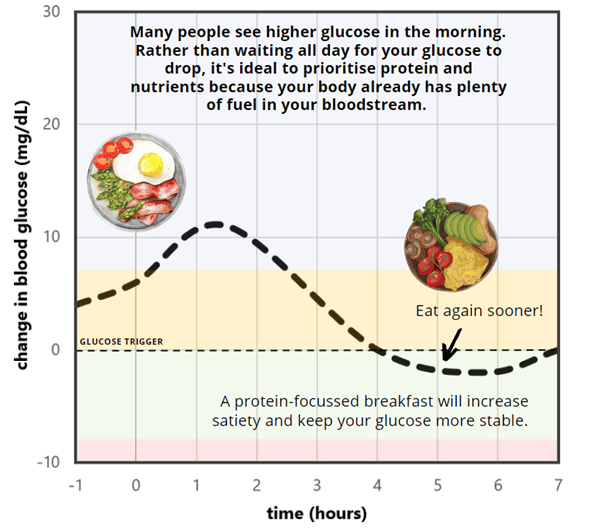

Many people find their glucose is elevated in the morning due to the Dawn Phenomenon. This is often the case for people on a lower-carb diet or with some insulin resistance.

Again, you don’t have to wait all day to reach your trigger. This can lead to excessive hunger later in the day and often poorer food choices. Most people also find getting enough protein and nutrients with one meal a day harder.

Instead, when you feel hungry in the morning, you can prioritise a higher protein % meal (e.g., greater than 40% protein with at least 40 g of protein). The lack of carbohydrates and the small insulin bump from the protein often causes blood glucose to drop after a protein-focussed meal.

Prioritising protein at your first meal means you reach your trigger sooner and can eat a second meal when hungry. A protein-focussed first meal also provides stable glucose throughout the day, ensuring adequate protein and increasing satiety.

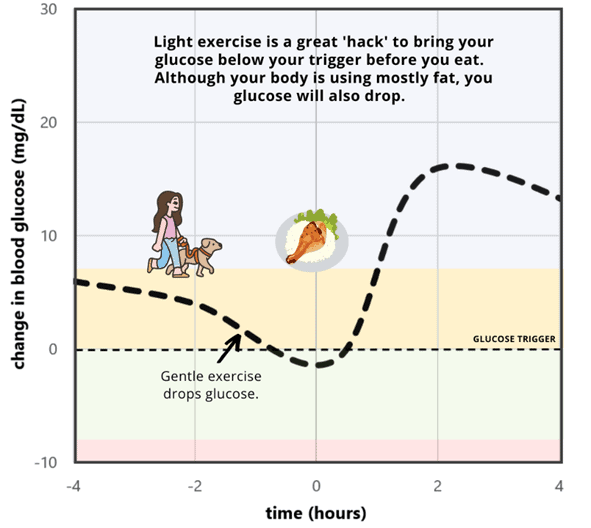

Light Exercise

Paying attention to your glucose can also motivate you to get moving. A short walk or gentle exercise will help lower your glucose if your glucose is elevated before your normal mealtime.

Intense Exercise

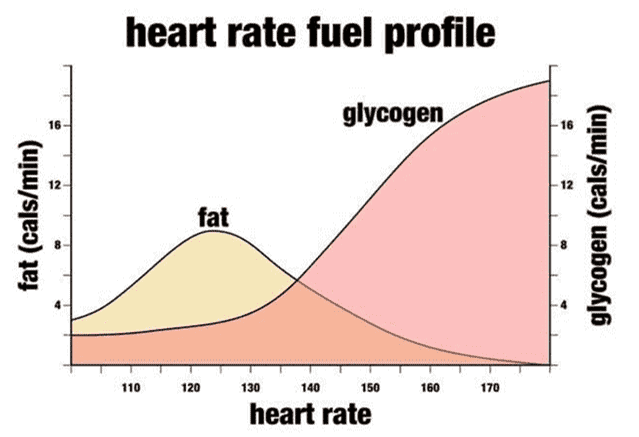

Exercising with a lower heart rate (i.e. zone 2) tends to use more fat than glucose, so your body doesn’t release more glucose into the bloodstream.

However, vigorous, high-intensity exercise often raises glucose because your body dumps stored glucose into your bloodstream to ensure you can run away from the lion. This elevated glucose often means you don’t feel hungry immediately after exercise, but as your muscles suck in the glucose from your blood, you can quickly find yourself extremely hungry.

While you don’t need to eat immediately after your workout, it’s smart to prioritise a robust meal when you first start to feel hungry in the hour or two after your workout to avoid the binge response that often occurs when your blood glucose crashes.

The Data-Driven Fasting app will temporarily boost your trigger if your glucose is elevated due to exercise. Another strategy we use in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenge is to have one meal a day (i.e. “Your Main Meal”) that you eat after your workout regardless of your glucose.

Rescue Carbohydrates

By now, you may be wondering, ‘what about carbs’? Don’t worry; they have their place too.

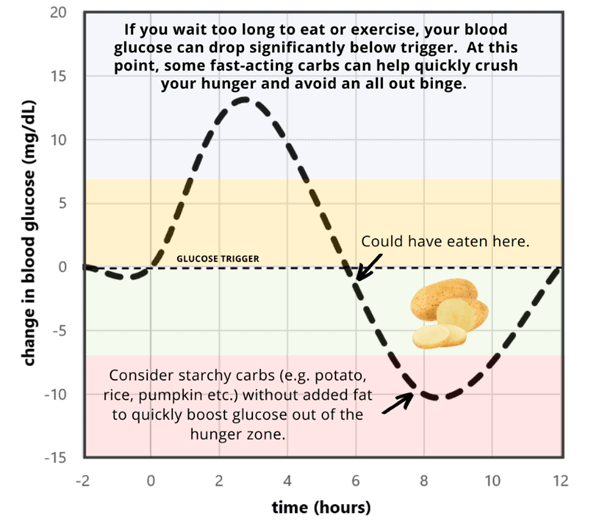

People with Type 1 Diabetes use carbs strategically to quickly bump their glucose back up into the normal range when their glucose drops below their target glucose range. This often does not require a lot of glucose, but it avoids the extreme hunger and raging appetite that happens when your glucose is lower than normal.

People who practice extended fasting also often find themselves extremely hungry due to low glucose levels and gravitate to energy-dense, nutrient-poor, low-satiety foods and meals. In Data Driven Fasting, we manage this risk by ensuring you learn to eat before your glucose drops too low.

If you can’t eat like a responsible adult after a fast, you likely pushed it too long and shouldn’t try as hard next time.

But if you find your glucose is significantly lower than normal for you because you have waited a little too long or have done a lot of intense exercise, you can use fast-acting carbs (e.g., potato, rice, pumpkin, etc.) to raise your glucose back into your normal glucose range quickly.

If you’re concerned about overdoing the carbs, check your glucose after the meal to ensure it didn’t go above the upper limit (i.e., 30 mg/dL or 1.6 mmol/L above your current glucose trigger) in the DDF app.

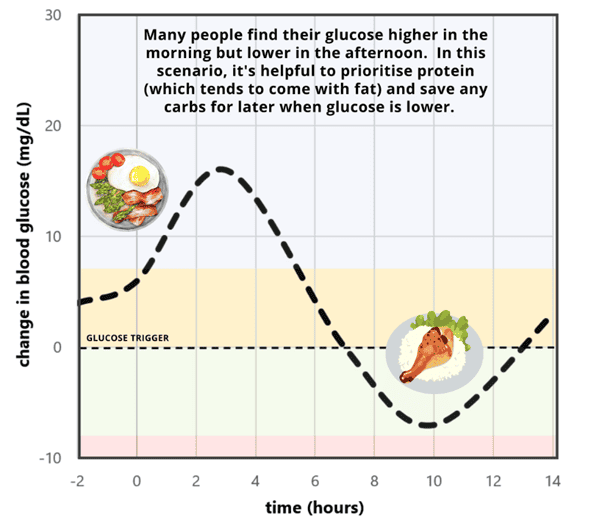

Intra-Day Carb Cycling

Many people find that their glucose drifts across the day, particularly if they do not consume a lot of carbohydrates during the day. Unfortunately, this can lead to excessive hunger and overeating later in the day.

If you find this is the case, it can be helpful to prioritise protein at your first meal and save any carbs for later to bump your glucose up into the normal range at night.

Some carbohydrates at night can also improve your sleep. Less fat at dinner often leads to lower waking glucose the next day.

If you’re concerned about overdoing the carbs, check your glucose after dinner to ensure it’s not rising above the upper limit on your hourly chart in the DDF App.

Using your glucose to validate your hunger quickly eliminates snacking, particularly late at night, which also helps to lower your waking glucose. You’ll also have a healthy appetite for a robust meal earlier in the day.

Optimal Eating Patterns for Weight Loss

Rather than resorting to one meal a day, extended fasting or alternate day fasting, with some practice, people can achieve balanced energy levels across the day with multiple meals while losing weight.

Many people settle into eating two nutrient-dense meals a day while chasing a lower trigger and losing weight.

If you keep an eye on portion sizes, getting in three meals a day is possible!

So, Data-Driven Fasting is not really ‘fasting’ in the normal sense; it’s really glucose-guided eating to ensure you validate your hunger and give your body exactly what it needs when it needs it!

Next Steps

- To find your personalised glucose trigger, you can use the DDF app here.

- To get a high-level overview of DDF, check out our DDF 101 course here.

- Join the next Data Driven Fasting Challenge, which includes a structured program, Live Q&As and community support.

More

- Data-Driven Fasting: How to Use Your Blood Glucose as a Fuel Gauge

- Hunger Training… How to Use Your Glucometer as a Fuel Gauge to Train Your Appetite for Sustainable Weight Loss

- How to Use a Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) for Weight Loss

- What Is the Ideal Blood Sugar Level for Weight Loss and Fat Burning?

- Data-Driven Fasting Challenge

Well done..

I suggest that this be made into a “kids” flip page ebook..

Meaning 1 graph/ page..

Single-sided…with no other words.

If someone clicks anywhere in the graph, the entire article page opens up.

Have page turning arrows, forward and backward in the margins..

Cheers!

This is a FANTASTIC article. So comprehensive! I sent it to someone who just found out they are a T2D and I’ve told them I will pay for them to do the upcoming challenge if they are interested after reading the article. So so awesome.

Thanks so much! I’m excited that the pictures are helping bring DDF to life!

This is the first time I have come across information for people who exercise regularly. It has validated my personal findings but made me wonder if there is anywhere I can find detailed use of applying these principles to frequent intense exercise. I am almost 70 years old but a regular marathoner, do faster work on the track and also weight train 3 times a week (moderately).

My nutritional needs are a bit complex, not least because of my age, and especially when doing multi day marathon events and/or heavy training. And that’s before I even look at tackling post marathon recovery training weeks. It is hard to balance things without it becoming a major drama. I must be able to do more than simply following a general plan of eating higher levels of protein and veggies. This approach leaves me with energy dips when training that then trigger cravings. For example, during the week after a marathon, I find myself craving fast carbs and eating in an unstructured and unhealthy way.

From June 2023, as part of Zoe research, I will be using a cgm for 12 months and want to do a longitudinal n=1 experiment about how to use this tool to improve my training and performance.

Any thoughts on this Marty? Is it something you would be interested in getting involved with, in a coaching sense? I want my n=1 to be long enough to see what happens both when I am focused and when I go off the rails for any reason. My gut feeling is that it could be a useful tool for full time athletes like me (my retirement career ?) Get in touch if you think this idea is of interest

Hey Chris. Glad you found the charts useful. The Supersapiens guys are doing some interesting work in this area too. They have a blog and a podcast that’s worth checking out.

Basically, you need to ensure your glucose is not going too low after the event to ensure you’re refilling your glycogen and ready for the next event.

I have some draft material in the works on exercise. Given lots of people have found this useful, I might do some charts to explain things.

Definitely eager to keep in touch on your n=1 with the CGM. Feel free to PM me on FB or MN.