Glucose spikes have become a widespread concern, thanks to the advent of continuous glucose monitoring.

Amidst the buzz of ‘glucose hacks’, there lies a spectrum of opinions. While some advocate for stringent carb-cutting, others debunk glucose fears surrounding everyday foods like oatmeal and bananas.

This article delves into the balanced narrative, shedding light on healthy glucose variability. It’s not just about dodging the glucose spike bullet and achieving flat-line blood glucose by eradicating carbs but mastering a balanced approach towards maintaining healthy blood sugar levels.

With insights rooted in evidence, this guide paves the way towards understanding the essence of glucose spikes and how to navigate them in your daily life.

Healthy People Have Stable Glucose

People who are lean and have plenty of muscle will see stable glucose levels regardless of what they eat. But, unfortunately, simply ‘hacking your glucose’ will not make you lean or metabolically healthy.

- Metabolically healthy people with more muscle and less fat have stable blood glucose, but

- Hacking a flatline blood glucose won’t automatically make you metabolically healthy or lean.

To understand why your glucose rises more or less than someone else, it’s important to understand that your body has (multiple) fuel tanks.

The figure below shows the different ‘fuel tanks’ in your body:

- Glucose in your blood,

- Glycogen (stored glucose) in your liver and muscles,

- Fat in your blood, and

- Body fat.

Lean people have plenty of room in their muscles and body fat to soak up the energy from the fat and carbs in the food they eat and put it into storage. Because the energy in their blood is not overflowing, their body fat stores are ‘unlocked’ and ready for easy access.

Meanwhile, as shown in the diagram below, someone who is insulin resistant (i.e. overfat) already has all their fuel tanks full to the brim. So when they eat, the energy from their food ‘backs up’ in their system. Thus, they see a larger rise in the glucose (and fat) in their blood.

Excess stored energy in your body is the root cause of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and most of our modern diseases. Fundamentally, it’s not simply the glucose spikes on our CGM that we should fear, but energy toxicity that leads to elevated blood glucose.

For more details, see:

- Oxidative Priority: The Key to Unlocking Your Body Fat Stores

- What Is Insulin Resistance (and How to Reverse It)?

- The Personal Fat Threshold Model of Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Obesity

Glucose Spikes and Reactive Hypoglycaemia

My wife and son have Type 1 Diabetes, so maintaining healthy blood glucose levels is a big deal in our house because:

- large glucose rises require large insulin doses to bring glucose back down,

- rapidly falling glucose levels drive increased hunger, especially when they drop significantly below normal, and

- it’s hard to get off once you’re on the glucose-insulin rollercoaster.

While not as severe, this can also occur in people with a functioning pancreas, particularly for those with some degree of insulin resistance — it’s known as reactive hypoglycaemia.

While not the only concern, large ‘spikes’ in glucose can be a concern. This 2006 JAMA paper showed that large glucose fluctuations after eating lead to increased oxidative stress (over and above the inflammation caused by elevated average blood glucose levels).

Large swings in glucose can also make us eat more. The Zoe ‘Big Dippers Study’ studied more than a thousand people wearing CGMs and found that people who saw a larger rise in glucose also saw a larger glucose dip before their next meal. The people who experienced a bigger dip tended to eat more and sooner than those who experienced a smaller rise in glucose.

While large rises and crashes in glucose lead to excessive hunger, some variability in your glucose is a healthy part of your appetite signalling. But before we eat, we should be hungry but not too hungry.

When our glucose drops significantly below normal, we get much hungrier – our lizard brain takes over, and we gravitate to energy-dense, low-satiety, nutrient-poor foods.

As shown in the chart below from our analysis of people using our Data-Driven Fasting app, lower glucose aligns with higher perceived hunger. So, dialling back your intake of refined carbs can be smart if you experience crashing energy levels and increased hunger after a higher-carb meal.

The Data-Driven Fasting app flags that you might have had more carbohydrates than you needed and overfilled your glucose fuel tank if you see a rise of more than 30 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) after eating.

What are Normal Glucose Levels?

Before you fall into the trap of fearing every ‘glucose spike’ on your CGM, it’s important to understand what normal, healthy glucose variability looks like.

A 2019 study using CGMs in healthy non-diabetic participants found that the average glucose was 99 mg/dL (5.5 mmol/L). The charts below show the distribution of glucose levels, ranging from 50 mg/dL (2.8 mmol/L) to 180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L).

Glucose rose above 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) only 2.1 % of the time and dropped below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) only 1.1%. So while metabolically healthy people see ‘spikes’ above 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L), this should be considered the exception rather than the rule.

In our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, where people focus on managing their glucose before they eat, participants see average glucose after meals of 110 mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L).

The average rise in glucose is 16 mg/dL or 0.9 mmol/L.

When glucose is elevated, your insulin will rise to keep more stored energy in storage while you use the excess glucose in your blood. In addition to holding your stored energy back in storage, your body will convert glucose to fructose via the polyol pathway and fat via de-novo-lipogenesis.

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) also form when protein and fats are exposed to elevated glucose levels. As a result, AGEs are a biomarker implicated in aging and the development, or worsening, of many degenerative diseases, such as diabetes, atherosclerosis, chronic kidney disease, and Alzheimer’s disease.

You don’t need to be concerned that the occasional glucose spike after a piece of fruit or intense exercise will kill you. But if your glucose rises by more than 30 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) after eating, the DDF app will flag that you might have consumed more carbohydrates than your body required and overfilled your glucose fuel tank.

Normal Glucose Variability

If you’re using a CGM, you will see a coefficient of variation (CV) and standard deviation in your glucose values.

Most experts like to see a CV of less than 33% for people managing diabetes, while metabolically healthy people should see a glucose variability of less than 20%.

The Dexcom Clarity report below shows my data from three months wearing a CGM, with average glucose of 5.0, estimated HbA1c of 4.8% and a coefficient of variation of 17.5%.

The Freestyle Libre also has a similar AGP report in the online reports in LibreView where you can check your glucose variability.

Swapping Fat For Carbs

When they see elevated glucose, many are tempted to simply swap the carbohydrates in their diet for fat. But this can only exacerbate the problem.

While fat doesn’t cause a rapid rise in glucose or insulin, you still fill your fat fuel tanks in your blood and body. As we mentioned above, this causes the energy to back up in your body. So, while your glucose won’t spike, it will stay elevated above your baseline for much longer.

People with Type 1 Diabetes still need insulin to cover a high-fat meal. A recent study of people with Type 1 Diabetes showed that without insulin:

- dietary glucose raised blood sugar in the first three hours or so, while

- dietary fat initially lowered blood glucose in the short term but caused a significant rise after three hours.

The Real Problem: The Area Under the Curve

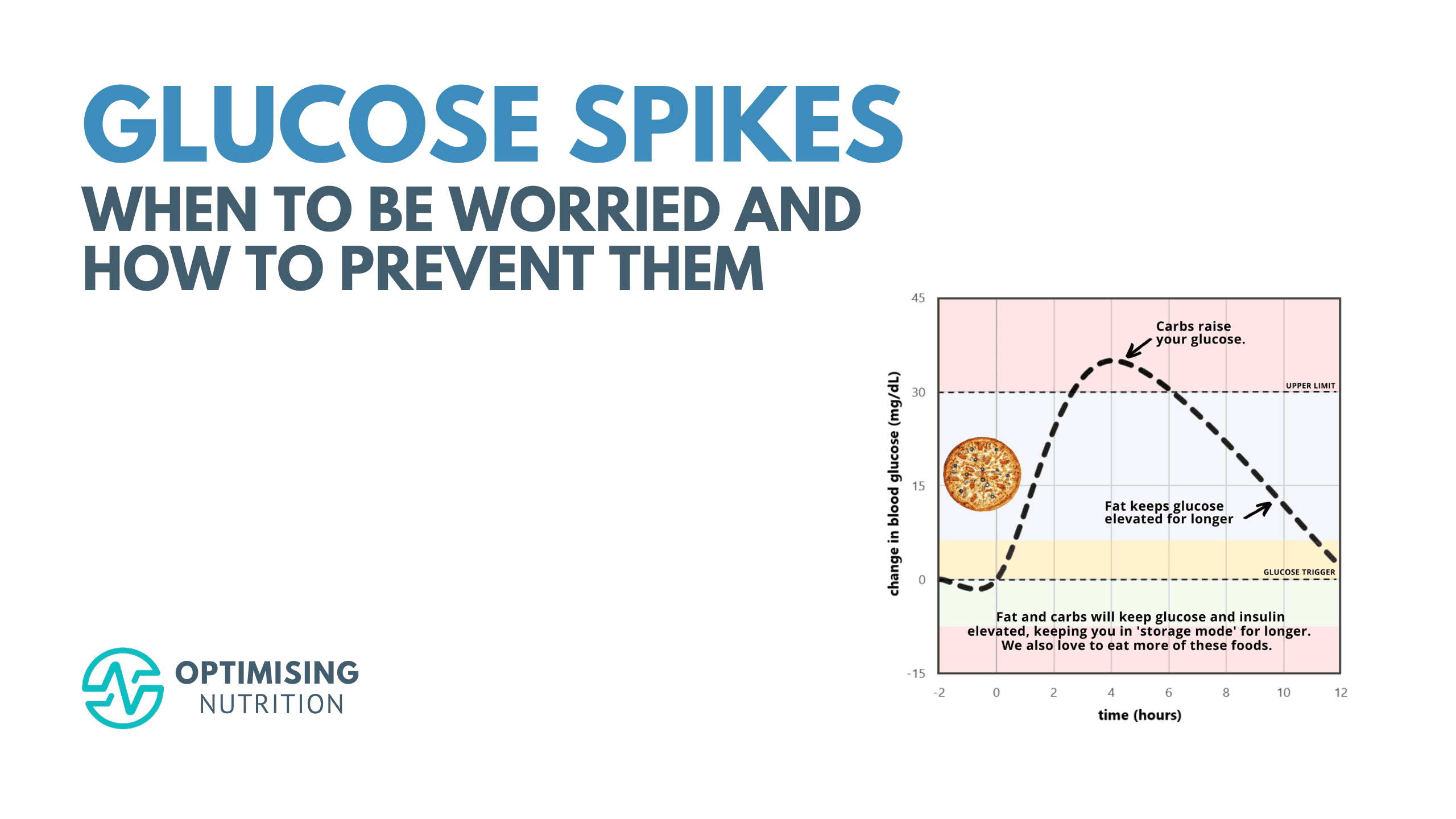

Carbohydrates raise your glucose and insulin, while fat keeps your glucose elevated for longer. So, rather than carbs OR fat, the real issue that causes our glucose to be elevated for longer is carbs AND fat.

What many people consider ‘bad carbs’ (like pizza, creamy pasta, cookies and croissants) are a combination of fat and carbs together, with minimal protein, fibre and nutrients.

Our satiety analysis shows that this combination of moderate carbs with moderate fat leads to a much higher energy intake. The chart below, created from more than three hundred thousand days of food logging, shows that we eat a lot more when our diet contains between about 30 and 55% non-fibre carbohydrates. Meanwhile, at either side of this fat+carb danger zone, low-carb or low-fat meals are much more satiating.

It would be nice if we could ‘have our cake and eat it too’ by hacking our glucose and still eat these foods. But the reality is, unless these ‘hacks’ lead to greater satiety and eating less, the energy from these hyper-palatable foods still has to be used, or it gets stored.

Having a glass of apple cider vinegar before your doughnut may reduce the glucose spike and decrease AGEs (though I’m not sure about this, as it will likely just flatten and prolong the elevated glucose). It may even help you lose your appetite for doughnuts if you have to drink ACV before every doughnut or piece of cake. But you can’t have your cake and eat it too—the cake and doughnut will still end up on your hips, bum and belly, contributing to the root cause of your dysregulated and elevated glucose—energy toxicity.

To reduce the area under the curve of your glucose and insulin response and increase satiety and reduce cravings, you need to dial back the carbohydrates and/or the fat in your diet while prioritising foods and meals that contain more protein, fibre and the essential nutrients you need from your food.

It’s Your Average Glucose That Really Matters!

The main problem with ‘glucose spikes’ is that, in the end, they increase your average glucose (which is what matters).

As shown in the figure below (from Impact of Glucose Level on Micro- and Macrovascular Disease in the General Population: A Mendelian Randomization Study), average glucose of 4.0 to 5.4 (72 to 98 mg/dL) aligns with the lowest risk of neuropathy and heart attack.

An HbA1c (a measure of your average glucose over three months) of 4.5 and 5.5% aligns with the lowest risk of dying of any cause.

So, rather than simplistically hacking our glucose spikes to look more like a metabolically healthy person, we need to find a way to lower our average glucose throughout the day. To do this, we need to draw on our stored fat and glucose to BE metabolically healthy.

It’s Your Glucose BEFORE You Eat that Matters

Rather than focusing on the spikes after eating, the best way to use your glucose to lose weight and become metabolically healthy is to focus on your glucose BEFORE you eat. If your glucose is just below normal for you before you eat, you know you’re draining your glucose and fat fuel tanks.

If you’re using your glucose as a fuel gauge to guide when to eat, the best way reduce the area under your glucose curve is to focus on dialling back both the fat and glucose in your meals while prioritising protein, fibre and essential nutrients to increase satiety.

As you chase a lower premeal glucose trigger, as we do in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, you will address the root cause of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome — energy toxicity — rather than simply hacking the symptom.

Summary

- Large glucose spikes are typically a symptom of poor metabolic health.

- Reducing the amount your glucose rises by reducing the carbohydrates in your diet can be helpful to achieve normal glucose variability.

- But to address the root cause of metabolic syndrome, you need to reduce the area under the curve glucose and insulin response after you eat.

- A lower premeal glucose before you eat will ensure you are tapping into your stored glucose and fat, leading to fat loss, improved metabolic health and, thus, lower glycemic variability.

I really appreciate this article and think DDF work! I did read Jessie’s book and 2 of the hacks have helped me a lot to lose those last few pounds and keep them off easily. Starting with greens and veggies and only having something sweet at the end of a meal have been life changing. I know that I’m insulin resistant so it won’t work for me to eat high carb foods. For me, eating a small cold sweet potato at the end of dinner or some other unrefined carb is what works. Once in a while, I may have a low carb treat and having it at the end of a meal instead of for a snack is a great hack. I’ve been taking my blood sugar long enough to know I can’t eat cake and other regular desserts at the end of a meal like Jessie and expect my bg to go down within 2 or 3 hours. Because of this article, I am going to try and have less fat at my dinner meal since my fasting bg is a little high. Thanks! Marty, I really appreciate your science behind everything!

Thanks Mindy! Best of luck on your journey!