Dive into a world where your nutritional choices are backed by real-time data from a Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM).

In a society where metabolic health is a rare treasure, understanding your body’s glucose response to foods is a roadmap to this treasure. The CGM, your personal health companion, sheds light on how your daily dietary choices impact your blood sugar levels and, in the grander scheme, your metabolic wellness.

This article unfolds the intricacies of CGM data, making it a compelling narrative for anyone keen on aligning their nutritional habits with their metabolic health goals.

Journey with us as we explore how to interpret CGM readings to foster a harmonious relationship between what you eat and how your body responds, setting a foundation for improved metabolic health and vitality.

- Introduction

- What Is Your Goal?

- Your Dual-Fuelled Metabolism

- It’s the Area Under the Curve that Matters!

- The Most Effective Way to Lower Your Glucose

- Why Glucose Spikes Are Bad

- What Is a Normal Healthy Rise in Glucose?

- Carbs Provide the Most (Short-Term) Satiety

- Fat Provides Flatline Glucose and the Lowest Long-Term Satiety

- So, What Can I Eat?

Introduction

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) can provide powerful insight into how you respond to food. The data from your CGM can help you make better food choices and fuel your activity.

However, more data is not always better. Too much data often leads to confusion and overwhelm. As you will see, CGM data can lead you to be more confidently wrong if misinterpreted.

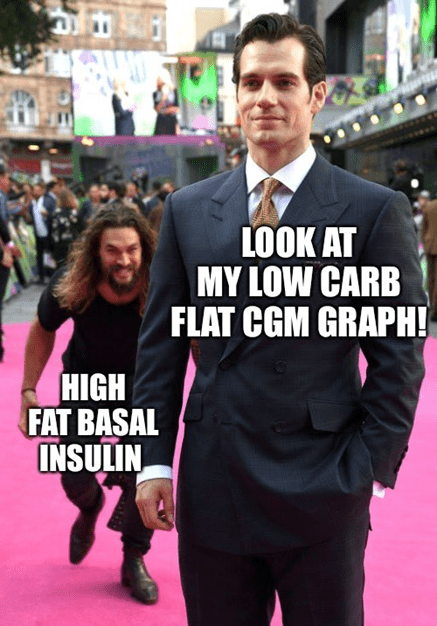

Metabolically healthy people often have low and stable blood sugars. But simply ‘hacking’ your glucose to achieve flat line blood glucose levels won’t cause you to lose weight and be metabolically healthy. It might even do the opposite.

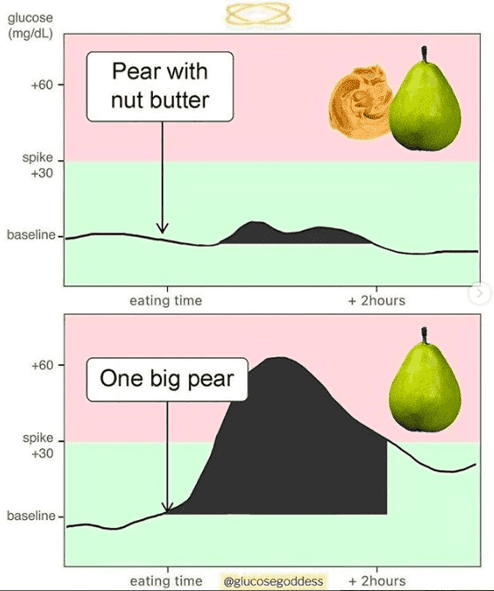

Images like the one below have been popping up all over social media. This one is from Jessie Inchauspé, ‘The Glucose Godess’, who has 1.2 million followers on Instagram. Recently in our Data-Driven Fasting Facebook Group, there was a massive thread about how these CGM charts should be interpreted, with many conflicting opinions.

So, in this article, I want to provide some insight that I have gleaned from:

- Data from more than five thousand people who have tracked their glucose in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges;

- Guiding thousands of people to dial in their macros over the last five years in our Macros Masterclass;

- living with my wife and son, who both have Type-1 Diabetes and rely on their CGM data; and

- my own CGM data.

Most of the time, we only focus on the changes in our blood sugars for an hour or two after eating. However, as you will see, your CGM can provide much more valuable data if you stand back and look at the big picture.

Rather than just managing the blips on your CGC, you can use your glucose as a fuel gauge to guide what and when to eat.

The information in this article will help you understand how to use your CGM data to achieve the weight loss and improved metabolic health you desire.

What Is Your Goal?

But the first question when interpreting your CGM data is, what is your goal?

Context is critical. To illustrate, let’s look at a few scenarios:

- Diabetes management;

- for athletes; and

- Weight loss and improved metabolic health.

Blood Glucose Management

My wife and son maintain a healthy weight and use exogenous insulin to manage their Type-1 Diabetes. Their primary goal is to keep their blood glucose levels in the normal healthy range. CGMs, and the closed-loop artificial pancreas systems that rely on them, are game changers for people with Type-1 Diabetes.

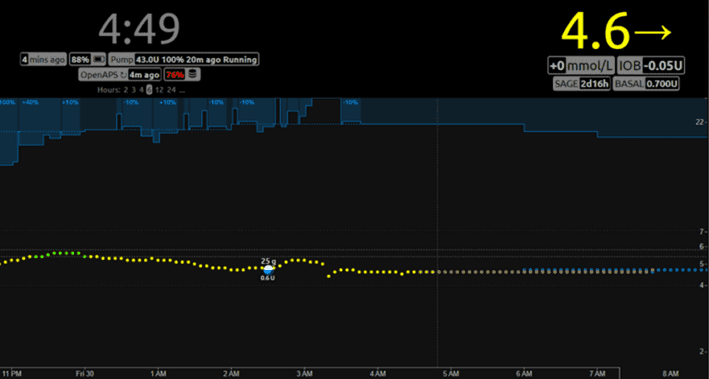

The image below shows my wife’s closed-loop artificial pancreas system. The blue bar at the top shows how the artificial pancreas algorithm constantly adjusts her insulin to keep her glucose in the normal healthy range. We can learn a lot about how a healthy pancreas operates by watching how the algorithm responds to different foods, exercise, sleep, stress and hormones.

For people managing diabetes, dialling back carbs, prioritising protein, and getting most of their energy from fat have helps keep them off the blood sugar rollercoaster and reduce the insulin they need to inject for food.

Per Dr Berstein’s Law of Small Numbers, smaller insulin doses lead to more minor errors, which yields more predictable blood glucose levels. For more, see:

- How to Optimise Type-1 Diabetes Management (Without Losing Your Mind),

- What Does Insulin Do in Your Body? and

- What Is Insulin Resistance (and How to Reverse It)?

But, as you will see, simply switching carbs for fat to stabilise blood glucose is not necessarily optimal for people whose primary goal is to lose body fat, reverse their insulin resistance and improve their metabolic health.

Exercise Fuelling

CGMs also give endurance athletes fascinating insight that they can use to optimise how they fuel their exercise.

The team at Supersapiens are doing some fascinating work in this area, led by Phil Sutherland, a cyclist diagnosed with T1D. Phil realised that endurance athletes with functioning pancreases could also use their valuable live CGM data to fine-tune their race fuelling.

Athletes can use their CGM data to ensure they don’t run out of fuel during long events. Supersapiens talk about fuelling to stay in the ‘glucose performance zone’.

If you want to set a new personal record (PR), shave fifteen seconds off your mile time, or lift more, you don’t want your blood sugar to be below what is normal for you. Topping up with energy from carbs and fat can ensure you don’t run out of fuel while keeping your glucose stable.

While it might be helpful to monitor your fuel gauge via your CGM if you’re running a marathon, most of us mere mortals have enough glucose in our bloodstream to do an hour or so of exercise without running out of glycogen.

Lower-intensity activity is a great way to bring your glucose down if you need to drain some of your energy reserves and lose weight. It won’t leave you ravenously hungry afterwards, which can undo all your hard work.

After exercise, it’s wise to refuel with a robust meal to bring your glucose back into the normal healthy range. If you’re trying to lose weight, choosing a nutritious meal with less carbs and fat is wise to give your body the nutrients it needs with less energy.

If you’re interested in learning more about using your CGM to optimise your exercise and physical activity, you can read more about it here.

Weight Loss and Metabolic Health

Because most people are considered metabolically unhealthy and overfat these days, there is a sizable interest in weight loss, improving metabolic health, and reversing insulin resistance.

Many companies like Levels, NutriSense, Signos, and January AI market CGMs directly to health enthusiasts who don’t have diabetes. Their simple message is that you should ‘try to limit high blood sugar spikes and keep blood sugar within a relatively healthy range’ or ‘keep your blood sugar as stable as possible.’

These companies have staff doctors who prescribe CGMs your medical insurance and then foot the bill. The user then pays for an app that guides their food choices to stabilise their glucose. While this is a lucrative business model, it may not be the optimal approach if your primary goal is weight loss, reversing your insulin resistance or improving your metabolic health.

Lean and metabolically healthy people have stable blood glucose but stabilising your blood glucose will not make you lean and metabolically healthy.

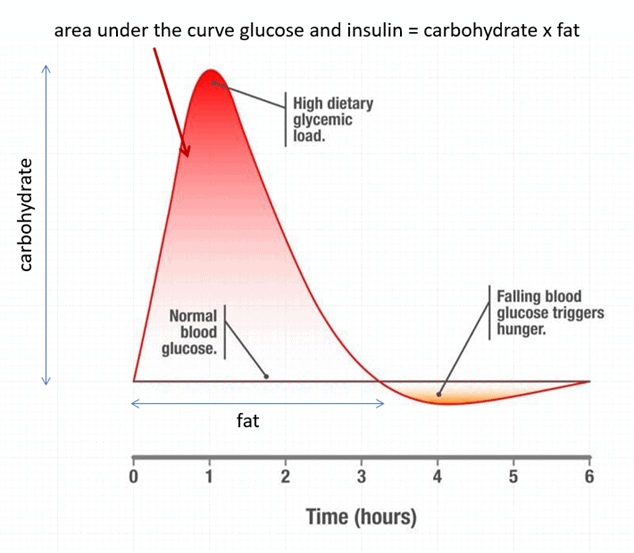

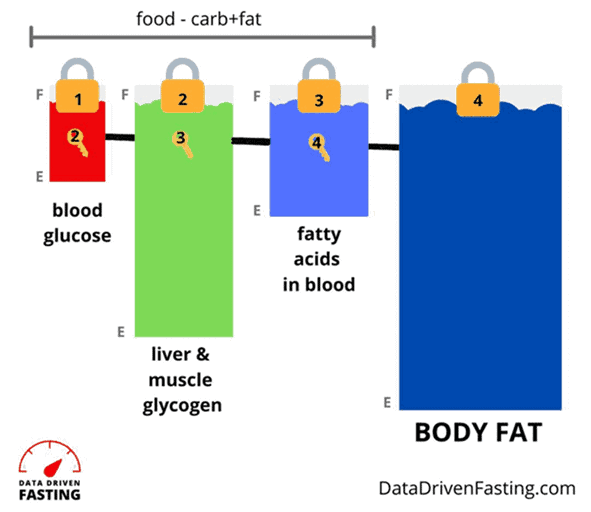

The image below shows how dietary carbohydrates cause a short-term glucose spike, raising insulin in the short term. However, dietary fat keeps glucose and insulin elevated over the long term. Foods that combine fat and carbs together (like pizza, cookies or creamy pasta) can keep your glucose and insulin elevated for many hours or even days!

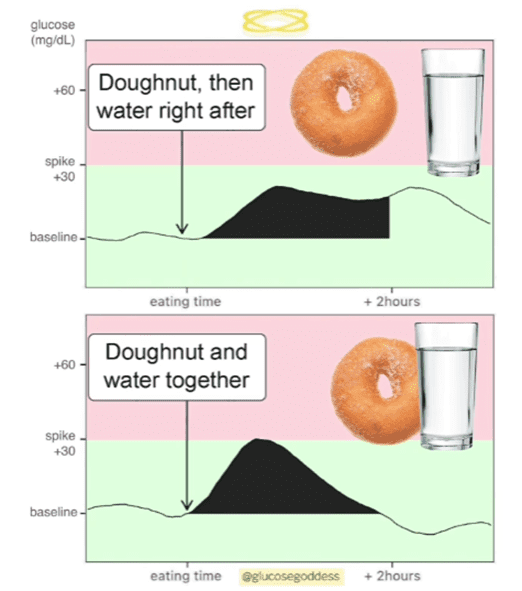

Many people have devised creative ways to ‘hack’ their glucose, like switching up the order they eat their food, drinking vinegar or water before or with their meals, and even ‘clothing their carbs’ with fat to stabilise blood glucose.

Simplistically focusing on the rise in glucose in the first two hours after eating only considers the impact of carbohydrates, which is only part of the story. Aiming for ‘flatline’ glucose can lead to overconsuming low-satiety, nutrient-poor high-fat foods. Hacks like adding fat to your carbs will drive you to eat way more and gain fat!

While these hacks may help you tame your glucose in the short term, they won’t improve your metabolic health unless they lead to greater long-term satiety. Only when you reach long-term satiety will you be able to eat less, lose weight, decrease your insulin resistance, and reverse the root cause of your metabolic dysfunction: energy toxicity.

A doughnut is still a doughnut, regardless of whether you successfully hacked your glucose to be more stable.

Ready to learn more?

Let’s dive in.

Your Dual-Fuelled Metabolism

To understand how to use glucose to empower your fat loss journey, we need to zoom out and look at the big picture.

Your body can run on various fuels, including alcohol, protein, and ketones. But carbohydrates and fat are your two dominant fuel sources.

While we can measure the glucose in our blood easily, unfortunately, we can’t measure the fat in our blood continuously (yet). But our long-term glucose response can give us some clues. Because glucose needs to be used first, your glucose can help you understand if your fat fuel tanks are also full.

To help explain this concept, the image below shows a pictorial representation of your body’s fuel tanks in order of how we use them.

- First, you will use the glucose in your blood;

- Then you can access the glycogen in your liver and muscles;

- Next, you can access the fat in your blood; and

- Finally, you can use your body fat stores (i.e., your adipose tissue).

You can think of your various fuel tanks as if they’re stacked up on top of each other. So, when you measure your glucose, you’re measuring all of the fuel tanks in your body.

You only have limited space to store glucose in your body, which amounts to about 2,000 calories. Glucose is a volatile, fast-burning fuel your body doesn’t want too much of in your bloodstream. Thus, it’s tightly regulated in a narrow range.

Due to a principle known as oxidative priority and the fact that you can’t store much glucose, your body prioritises burning glucose over fat when you have a lot of it in your system.

When you eat a high-carb meal, the glucose in your blood rises quickly. Your pancreas then produces more insulin to keep all the other fuels in storage so you can use up the energy that just came in through your mouth.

Although we usually focus on the change in insulin immediately after eating (i.e., bolus insulin), your pancreas constantly releases insulin throughout the day and night to stop all your stored energy from flowing into your bloodstream at once

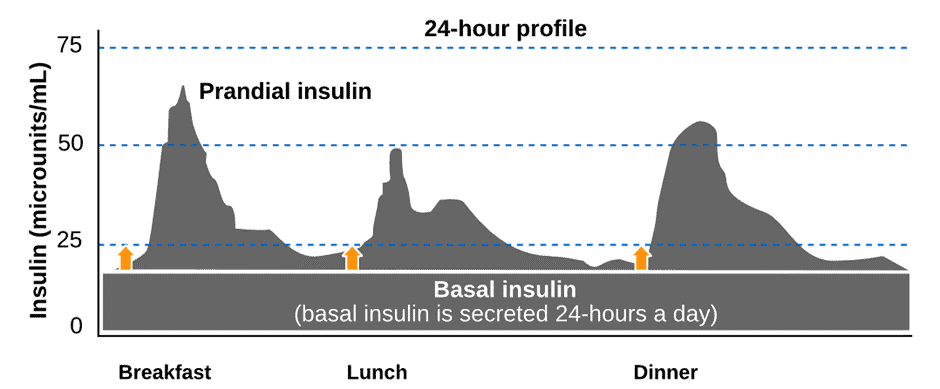

The image below depicts our basal and bolus (postprandial and prandial insulin). Note how your pancreas produces basal insulin to regulate fuel flow into your bloodstream.

We know from people who have Type-1 Diabetes and eat a higher-carb diet that their insulin is split 50:50 between basal vs bolus. However, for someone with T1D on a lower-carb or keto diet, their basal insulin makes up 70 to 90% of their daily insulin demand.

While you may have a working pancreas, we can take our observations in T1D populations and apply them to the masses of people with metabolic dysfunction, T2D, and erratic blood sugars.

Delaying meals and reducing carbohydrates will help you lower the glucose levels in your blood. When your blood glucose lowers, your pancreas reduces the amount of insulin it produces so your liver can release stored energy into your bloodstream. Glucagon—the opposing and antagonistic hormone to insulin—pushes glycogen from your liver into your bloodstream to fuel your activity and body functions between eating periods.

At this point, you will have successfully reduced your blood sugars. But there’s still a catch! If you’ve swapped carbs for dietary fat, you’ll be topping your fat fuel tanks even though your blood glucose might be more stable. Hence, you won’t be able to unlock the fat in your adipose tissue, and your basal insulin will stay high.

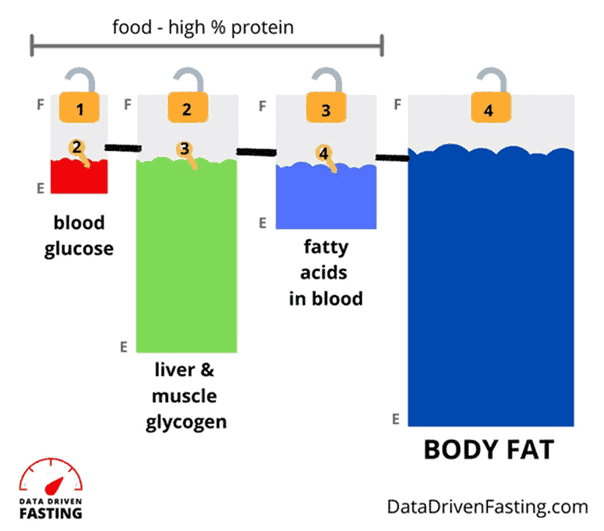

The secret is to dial back both carbs and fat while prioritising protein and nutrients so you can deplete the glucose and fat in your body while maintaining a high degree of satiety so that you won’t fall victim to your cravings a few weeks in. Only then will your basal insulin levels drop, and you will unlock your stored body fat!

For more on this, see:

- Oxidative Priority: The Key to Unlocking Your Body Fat Stores

- Personal Fat Threshold Model of Insulin Resistance, Diabetes and Obesity vs the Carbohydrate Insulin Model

- What Is Insulin Resistance (and How to Reverse It)?

- What Does Insulin Do in Your Body?

It’s the Area Under the Curve that Matters!

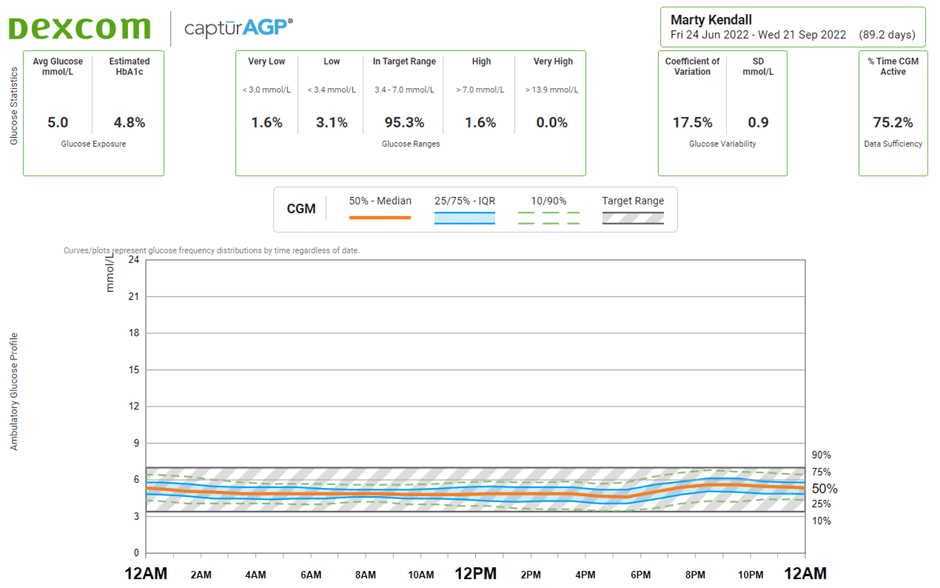

Now, let’s zoom back in to look at your blood glucose. The image below shows my CGM data over three months.

In the top left, you can see my average glucose over three months is 5.0 mmol/L (90 mg/dL), and my estimated HbA1c is 4.8%. It’s critical to consider your glucose across the whole day. The higher your average, the more energy you have floating around your system from all sources.

To access your body fat, you need to lower your average glucose—not just after meals—to drain your liver glycogen stores and the fat stored in your body.

Trying to measure insulin by fixating on the change in glucose over those two hours after you eat is like trying to estimate the ocean’s volume by measuring the height of the waves at the beach.

Once your glucose is in the normal healthy range (e.g., with a rise after eating less than 30 mg/dL or 1.6 mmol/L), there’s no additional benefit in stabilising your glucose further, especially if you end up overeating fat to do it.

The Most Effective Way to Lower Your Glucose

The most effective way to lower your glucose is to abstain from eating. But, while people have fasted for up to a year, most of us find we need to eat more regularly. There’s a limit to how much fat you can access before it catabolises your lean muscle mass for energy.

Unfortunately, when we try not to eat for longer than we’re used to, we also tend to gravitate towards nutrient-poor, ultra-processed, hyper-palatable, carb-and-fat-combo foods. These energy-dense foods not only refill our fuel tanks quickly, but they also provide minimal nutrients, like protein, minerals and vitamins.

We feel miserable and risk losing precious muscle and gaining fat over the long term due to our poor food choices.

The solution to progressively reduce your glucose levels so you can access body fat is to find a way of eating that allows you to feel satisfied while eating fewer calories. This will allow the glucose in your blood to slowly be drained, followed by the fat in your body.

Fine-tuning your meal timing using your glucose and eating for satiety makes this possible. It’s much more useful to manage your glucose before you eat to drain the glucose and fat in your body, but we’ll dig into that more later! Let’s look at why you should avoid glucose spikes more often than not.

Why Glucose Spikes Are Bad

The first thing most people realise when they start wearing a CGM is that carbs spike their glucose. As a result, low-fat foods like fruit and oats suddenly become evil, labelled as foods we must avoid at all costs.

However, if we add fat to everything, the glucose curve behaves better. Some refer to adding fat to a carby food to blunt a glucose response as ‘clothing your carbs’. However, this can negatively impact your metabolic health if taken to extremes as you’re simultaneously filling your carb and fat fuel tanks.

While avoiding overfilling your glucose fuel tank is wise, it isn’t the only thing to be mindful of. In our Data-Driven Fasting Challenge, we advise people to reconsider foods that spike their blood sugar by more than 30 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) after eating.

Stable blood glucose can help to improve your medium-term satiety. If your blood glucose rises a lot, your pancreas releases more insulin, so your body shows the release of stored energy until it clears the glucose in your blood.

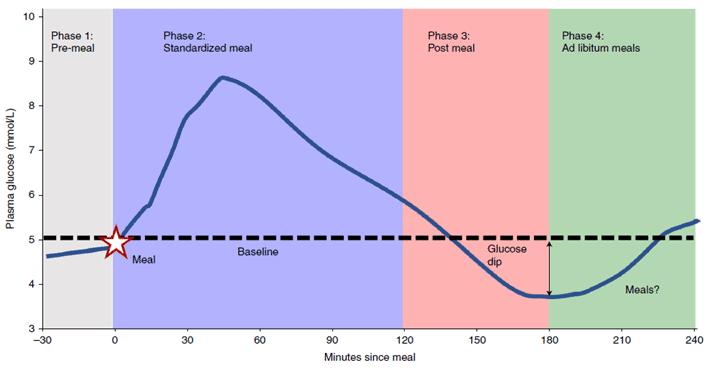

While erratic glucose spikes aren’t great, the real problem comes when your glucose crashes below your norm. This rapid drop in blood glucose not long after eating is called reactive hypoglycaemia.

Once you’ve hit your lowest glucose low, the amount of glucose available for your brain and muscles is limited. Thus, you feel highly motivated to eat to bring your sugars up into the normal range quickly, so you gravitate towards the most energy-dense foods you can get your hands on. Unfortunately, this keeps you on the endless blood glucose rollercoaster, which drives you to make worse food choices than if your glucose was in the normal healthy range.

Continually eating more than we otherwise would lead us to get fatter. More fat requires more basal insulin to hold in storage, meaning our average insulin and blood sugar levels throughout the day drift up.

Zoe’s recent ‘Big Dippers Study’ showed that people with insulin resistance had larger blood glucose swings when eating carbohydrates. Significant rises led to larger falls, forcing someone to eat sooner and more.

What Is a Normal Healthy Rise in Glucose?

In our Data-Driven Fasting Challenge, we suggest people review foods that raise their sugars more than 30 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) after eating, especially if their glucose comes crashing down and they feel ravenous a few hours later.

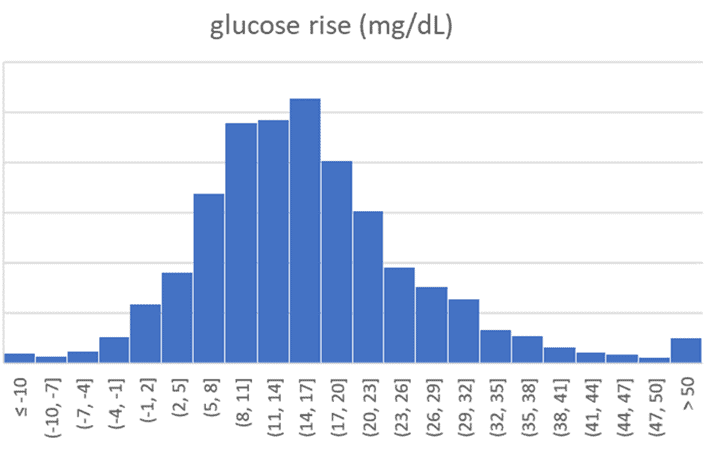

Interestingly, we find most people in our challenges—who often come from a low-carb or keto background—already have reasonably stable blood glucose levels. The average rise in glucose after eating is 0.9 mmol/L (16 mg/dL), as the distribution chart below shows.

For these people, the next step is to dial back their dietary fat consumption so their blood sugars can return to below their personalised blood glucose trigger sooner, and their bodies can use the fat they’ve stored away rather than the fat in their diet.

While the mainstream has glamourised flatline glucose, it is not necessarily better. If you have to overdo it on dietary fat to keep it this stable, it might be hurting you more than it’s helping!

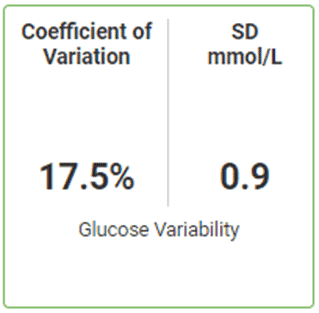

The snip below shows my glucose variability from my CGM. Unfortunately, because most CGM-related studies generally use people with diabetes, there isn’t much research on healthy glucose variability. However, many people believe that under 20% is a healthy goal.

Some glucose variability is normal, healthy, and beneficial and is part of the swings of hunger and satiety. From our experience over the years with our programs, we’ve seen many people on very high-fat keto diets who also practice extended fasting who are obese and have lost touch with their innate hunger signals.

For more, see What are Normal, Healthy, Non-Diabetic Blood Sugar Levels?

Carbs Provide the Most (Short-Term) Satiety

You may be interested to know that a high-carb meal will provide the most significant short-term satiety.

In the study Interrelationships among postprandial satiety, glucose, and insulin responses and changes in subsequent food intake, Susana Holt et al. showed the foods that raise glucose and insulin the most over two hours—high-carb foods that spike your blood glucose—provide the most satiety over the first two hours.

Your body realises it has a ton of fast-burning fuel and quickly turns off your appetite until you can clear the glucose from your bloodstream. But this ‘fun fact’ is irrelevant if you’re starving and hungry three hours later because your blood glucose levels have crashed! Hence, focusing on satiety throughout the day is more helpful.

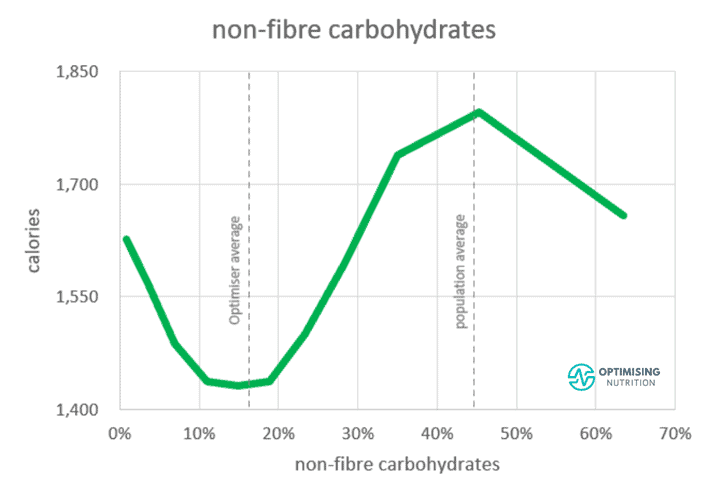

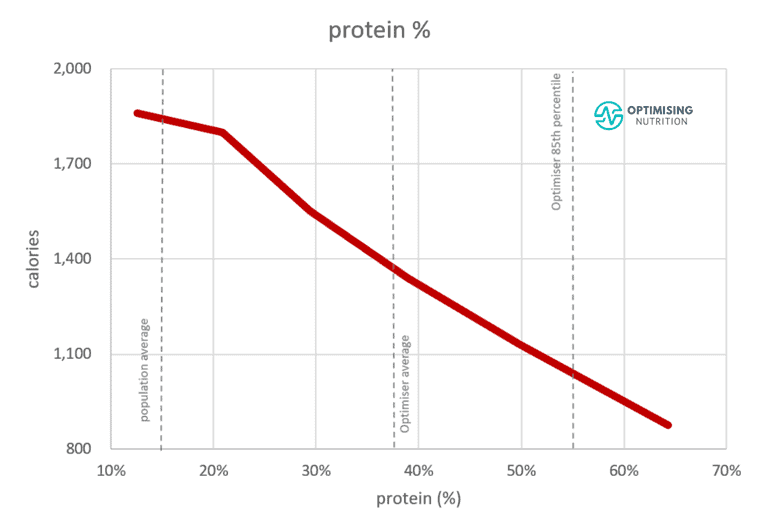

The chart below shows the relationship between carbohydrate and daily calorie intakes from 141,171 days of food logging data from Nutrient Optimiser users. Here, we see that we eat the least when we consume 10-20% of our daily energy from non-fibre carbohydrates.

However, we eat the most when our diet consists of around 45% non-fibre carbohydrates, and the rest of the energy comes from fat. This is basically the formula for hyper-palatable junk food like cookies, cakes, and pizza.

Combining carbs with fat, or ‘clothing your carbs’, is a great—and tasty!—way to stabilise your blood glucose in the short term. Unfortunately, it’s also a great way to keep your blood glucose and insulin elevated for the LONGEST time, fill both fuel tanks, and make you fat!

For more details, see:

Fat Provides Flatline Glucose and the Lowest Long-Term Satiety

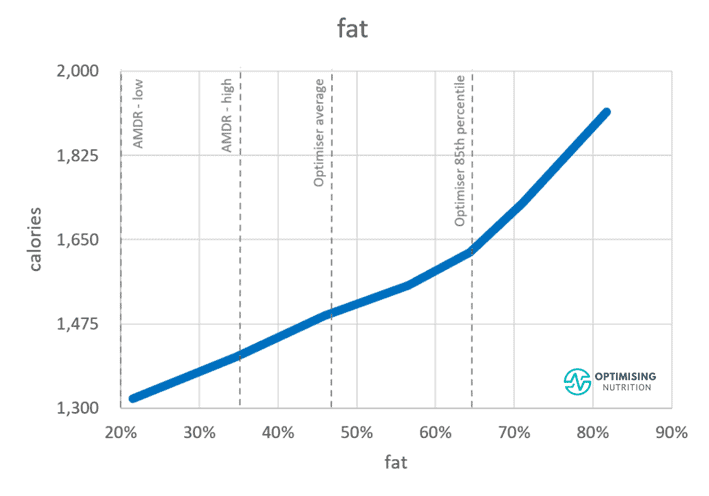

Many people quickly realise that the best way to stabilise their glucose is to avoid carbs and eat fatty foods.

This was the basic foundation of the keto movement. Many people believed that they could switch off their insulin and lose fat if they could keep their blood glucose stable. Today, most people have now realised that this is not the case.

The number of micronutrients, or the amino acids, fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals in your food, are critical for satiety; our bodies will respond with increased cravings if we don’t get enough micronutrients, which ensures our bodies have all the raw ingredients they need to function.

Fat contains the least amount of micros per calorie and thus provides the least satiety of any macronutrient. Therefore, to lose body fat and reverse your insulin resistance, you may need to dial back your dietary fat as well as carbs to lose fat from your body.

For more details on this, see:

- Insulin is NOT Making You Fat (and Here’s Why)

- The Carb-Insulin Hypothesis vs. Protein Leverage Hypothesis of Obesity

So, What Can I Eat?

Hopefully, you can see that simply ‘hacking’ your glucose by eating more fat to keep it stable will not necessarily help you lose weight, reverse your insulin resistance, or improve your metabolic health.

While it’s a great idea to reduce carbs to stabilise your blood glucose into the normal healthy range, simply swapping carbs for fat or adding fat to your carbs may cause you to eat more, gain weight, and increase your insulin and blood glucose levels.

But there is good news! You can use your glucose to guide what and when you eat. Your blood glucose levels before you eat is the most critical marker to manage to reduce your glucose across the day.

If your glucose is higher than usual, you might try waiting a bit longer until you eat again so you can use up some of the glucose in your bloodstream. If you’re starving and your glucose is above normal, you probably have plenty of glucose and fat in your bloodstream, so you might consider prioritising protein and nutrients.

As shown below, protein is the most satiating macronutrient. We need enough of it each day to maintain and repair our muscles and organs and to synthesise neurotransmitters, hormones, and enzymes, which drive your body’s day-to-day processes.

Many people in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges find that when they prioritise protein, their blood glucose falls after they eat, and their cravings are satisfied.

Higher-protein whole foods and meals often come packaged with energy from fat, which helps keep glucose stable.

So, where does this leave carbohydrates? Well, they still have a role! When your glucose drops well below your normal, and you’re starving, a little bit of fast-acting starchy carbs can help quickly bring your glucose back into the normal range. This will switch off your appetite quickly, so you don’t find yourself face down in a pizza box, nose deep in a cookie jar, or losing the battle with a whole jar of peanut butter.

To summarise how to eat for your blood sugar and to help you make the most of your blood glucose data, the table below shows the guidance our Data-Driven Fasting app gives based on your blood glucose readings.

| Glucose | Guidance |

| Significantly above trigger | Whoops! Your glucose is still significantly above your average or Your Personal Trigger. Try waiting an hour or so until your glucose drops or do some gentle exercise, then retest. If your glucose is higher than normal from stress, exercise, poor sleep, pain, or fatigue, or if you’re nearing the start of your womanly cycle, you can tick one of the events in the DDF app to get a higher temporary trigger for the next 24 hours. This will allow you to eat until you’ve recovered. |

| Just above trigger | Your glucose is just above trigger. If you’re particularly hungry, go ahead and eat. However, be sure to prioritise protein and nutrients and consume less energy from carbs and fat so you can use your stored energy. |

| Just below trigger | Congratulations! Your BG is below trigger. It’s time to eat! |

| Significantly below trigger | Your glucose is significantly below trigger. It’s time to eat! Add some whole-food starchy carbs like rice, potato, beans, pumpkin or oatmeal so you can quickly bring glucose back up into your normal range. |

Summary

- People who are lean and metabolically healthy tend to have stable blood glucose. But using hacks to achieve flatline blood glucose won’t necessarily make you lean or metabolically healthy, especially if you end up overeating dietary fat.

- Carbs raise your glucose in the short term, but dietary fat will keep your glucose elevated for longer. So, to deplete your glucose and use your stored body fat, it’s smart to dial back both refined carbs and added dietary fat while prioritising foods with the protein and nutrients your body requires.

- You can use your glucose before meals to guide what and when to eat to reduce your average glucose across the whole day and allow your body to use your stored body fat for fuel, reverse your insulin resistance and improve your metabolic health.

Thank you Marty and for your wife who braved some ‘experiments’. My integration skills to obtain AUC s are a bit rusty but regarding say, the doughnut vs doughnut followed by water graph- but what if the doughnut was quite warm vs cold? Or the water was weak warm to hot tea without milk? Would temperature of beverage or food make a difference? What about ice-cold water vs warm water? Just trying work thru some variations.