Did you know you have an instantaneous fuel gauge that you can use to validate your hunger and confirm whether you need to refuel?

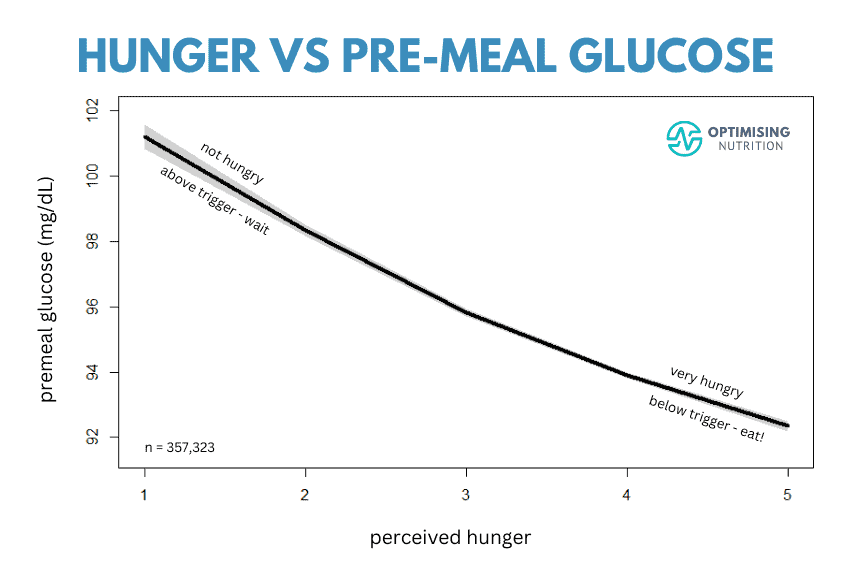

As shown in the chart below from our analysis of 357,323 premeal glucose values from 6,517 people using our DDF app, there is a tight relationship between hunger and blood glucose levels.

In our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, we guide our Optimisers to validate their hunger by testing their glucose before they eat so they can decide if they need food now or wait a little longer.

In this article, we’ll dive into the relationship between glucose and hunger and show you how to use it to guide when and what to eat to achieve your goals.

What Is True Hunger?

True hunger is a physiological, sometimes uncomfortable feeling due to a legitimate lack of energy or nutrients.

Signs of legitimate hunger include:

- stomach growling,

- headaches,

- light headedness,

- food focussed,

- can’t concentrate, and

- being moody and irritable.

Why Do We Eat?

Other than true hunger, there are many reasons we eat, including:

- boredom,

- stress,

- sadness,

- habit,

- social/celebrations and

- time of day (e.g. because it’s ‘breakfast time’).

Eating just because the food is available or because you suddenly can’t stop thinking about your favourite ice cream or the leftovers in the fridge can be confused with hunger.

Eating when we don’t need to is the primary reason most of us eat more than our bodies need, which leads to obesity, type 2 diabetes and all the other complications of energy toxicity.

Unfortunately, the foods that drive us to eat when we’re not hungry are often ‘empty calories’, providing energy without the nutrients we crave and need to thrive. These are the foods that we often feel ‘addicted to.

Opting for empty calories from ultra-processed foods is like spending your paycheck on plastic surgery before paying the rent and electricity bills. Eventually, it doesn’t end well.

The unfortunate reality is that 73% of the food expenditure in the US now goes to ultra-processed foods designed to be addictive, so you’ll buy more.

Can You Train Your Hunger?

Some people talk about ‘intuitive eating’ or ‘mindful eating’, but most of us find it hard to calibrate our hunger cues to nourish our bodies and maintain an optimal body weight in our modern food environment.

But the good news is that we can use our blood glucose to train our hunger.

A 2006 study, Training to Estimate Blood Glucose Form Associations with Initial Hunger, showed that people could learn to accurately estimate their blood glucose based on their hunger cues, especially at low glucose levels.

In 2015, the study Adherence to Hunger Training Using Blood Glucose Monitoring showed that pre-meal blood glucose was more effective than food tracking or daily weighing for weight loss.

This study inspired the creation of Data-Driven Fasting to help people train their hunger, guide their weight loss and improve their metabolic health. At the time, many people were diving into extended fasting practices that taught them to ignore their hunger. Unfortunately, this often caused them to lose their healthy sensation of fullness and satiety, which means they made poorer food choices and overeat when they allowed themselves to eat again, often leading to worse metabolic health.

Data-Driven Fasting uses a personalised glucose trigger, taken from the average glucose before you eat during the three-day baselining period. Going forward, the simple goal is to wait until:

- You are hungry enough to test your glucose and

- Your glucose is just below your current glucose trigger.

As shown in the chart below from the DDF app, to ensure you keep making progress, the personalised glucose trigger progressively updates based on the average of your premeal glucose values over the past seven days.

One of the keys to Data-Driven Fasting is to avoid excessive hunger by ensuring you don’t wait too long to eat. Excessive hunger makes it much harder to make healthy food choices when you eat again. When people test their glucose, we encourage them to imagine the number they might see after their meter counts down based on their hunger sensations. They can then record their hunger in the DDF app (as shown below).

People often ask if waiting a little longer would speed the fat loss process up. The answer is no.

Waiting until you’re hungry and have reached your trigger ensures you develop a consistent eating pattern that will set you up for the long term while making excellent weight loss progress.

The Relationship Between Your Normal Glucose and Hunger

After running twenty-seven Data-Driven Fasting Challenges over three years, we have a massive dataset to understand the relationship between blood glucose and hunger.

The table below shows the glucose analysis in relation to the individual’s average premeal glucose value and their rating of perceived hunger.

| perceived hunger | mg/dL | mmol/L | number | % |

| 1 | 5.3 | 0.30 | 11,144 | 3% |

| 2 | 2.3 | 0.13 | 31,286 | 9% |

| 3 | 0.8 | 0.04 | 97,515 | 27% |

| 4 | -0.6 | -0.03 | 143,771 | 40% |

| 5 | -1.6 | -0.09 | 75,910 | 21% |

The first thing to note is that most people wait until they are hungry but not too hungry most of the time (i.e. level 4 hunger, not level 5).

At level 4 hunger, they are, on average, 0.6 mg/dL (0.03 mmol/L) below their current trigger. Remember, waiting for longer is not better. Letting your glucose get too far below what is normal for you can lead to overeating, which means you need to wait longer before eating again next time.

People reached level 5 hunger (i.e. very hungry) 21% of the time, corresponding to 1.6 mg/dL or 0.1 mmol/L below their current trigger.

As shown in the chart below, people who were not hungry (level 1 hunger) were, on average, 5.3 mg/dL (0.3 mmol/L) above their trigger.

You don’t need to try to be a hero and wait longer. If most of your glucose values are below your current trigger, your trigger will continue to drop. A lower premeal glucose aligns with weight loss, improving waist-to-height ratio, lower blood pressure and lower fasting glucose.

Why Do We Get Hungry?

True hunger is a signal from our body that we need nutrients or energy, but there are several theories of hunger.

- In 1953, Jean Mayer proposed the glucostatic theory of appetite control based on the understanding that our appetite increases when glucose lowers.

- Shortly after this, in 1957, Kennedy proposed the lipo-static theory of appetite, which proposed that leptin rises and we get hungry when our fat stores are depleted.

- Meanwhile, in 1956, Mellinkoff proposed the aminostatic theory of appetite, whereby our hunger increases because we crave protein.

- Others have recently highlighted that we also crave minerals like sodium and calcium. Our satiety analysis also confirms this.

In summary, the reason we get hungry is fascinating and complex. But know that it’s time to eat if you’re hungry and your glucose is below normal for you.

How to Use Your Glucose to Guide WHAT You Eat

It’s ideal to eat before your glucose gets too low, but if you wait too long, the DDF app will suggest you use some fast-acting carbs to avert the emergency and prevent you from binging. This is similar to the approach someone with Type 1 Diabetes might make if they overshoot their blood glucose target.

But if all goes to plan, your blood sugar rises and falls gently below your trigger, and it’s time to eat again.

But suppose you do find yourself hungry, and your glucose is above your current premeal glucose trigger. In that case, you know that you don’t require carbohydrates. If you’re still overweight, you also know that you don’t need more fat. Your body is likely craving protein and nutrients.

So, if you’re truly hungry and still above your trigger, the DDF app will suggest you prioritise protein and nutrients with less energy from fat and carbs. This quantified mindful eating allows you to ensure that you are giving your body precisely what it needs when it needs it while also draining your excess energy stores.

Why Your Glucose is Such an Excellent Fuel Gauge

To understand why using your glucose to guide when to eat, we need to understand more about how the fuel tanks work in our bodies. As shown in the graphic below, your body contains several different ‘fuel tanks’:

- your body fat,

- the fat in your blood,

- the glycogen (stored glucose) in your liver and muscle, and

- the glucose in your blood.

Due to oxidative priority, your body must burn off the glucose backed up in your system before it gets on with burning the fat. Glucose is a volatile fuel, and there’s not much room to store it, so it needs to be used up as a priority.

Meanwhile, your body has heaps of room to store fat. When your body fat and liver are full, the excess energy from your diet ‘backs up’ into your bloodstream. The glucose effectively floats on top of all the other fuels. Hence, elevated blood glucose indicates that all your other fuel tanks are also full.

As you wait a little longer before your meals and prioritise nutrients over fuel from fat and carbohydrates, you allow all your fuel tanks to be depleted and ultimately use up your stored body fat.

Who knew the humble glucose meter could be such a powerful tool to train your hunger and guide your eating?

Summary

- Our analysis of 357,323 premeal glucose values from 6,517 people using the DDF app shows a clear relationship between our glucose and our true hunger.

- Your blood glucose before you eat can be a powerful guide to validate your hunger and food choices.

- Rather than waiting until your glucose gets too far below what is normal for you, developing a consistent routine where you are just below your trigger most of the time is ideal.

- If you’re truly hungry and glucose is above your current trigger, you can prioritise nutrient-dense foods to allow the energy in your blood and body to continue to be used.

Action Steps

- If you’d like to find your current premeal glucose trigger, you can take our DDF App for a free test run here.

- Meanwhile, you can join our next Data-Driven Fasting Challenge if you want more guidance.