Embark on an intellectual exploration contrasting the Carb-Insulin Model and the Protein Leverage Hypothesis in the realm of obesity.

This article meticulously unpacks these theories, offering a clear lens through which to view the often-debated topic of weight management.

By delving into the Carb-Insulin Model and the Protein Leverage Hypothesis, you’ll gain a profound understanding of how different macronutrients might influence your weight.

Unearth the wisdom embedded in these theories and chart a science-backed course towards your wellness goals.

- The Carb-Insulin Hypothesis

- Protein Leverage Hypothesis

- Carb-Insulin Hypothesis vs Protein Leverage Hypothesis

- Why Low-Carb Works

- Basal vs Bolus Insulin

- Reducing Carbs is a Smart Place to Start

- Fat Is NOT a Free Food!

- What’s the Solution

- Your Personal Fat Threshold and Oxidative Priority

- What to Eat to Increase Satiety and Reverse Insulin Resistance

- Summary

- More

The Carb-Insulin Hypothesis

While there are many iterations of the carb-insulin model, it generally goes like this:

- Someone eats carbohydrates,

- Those carbs raise their insulin, and

- They get fat.

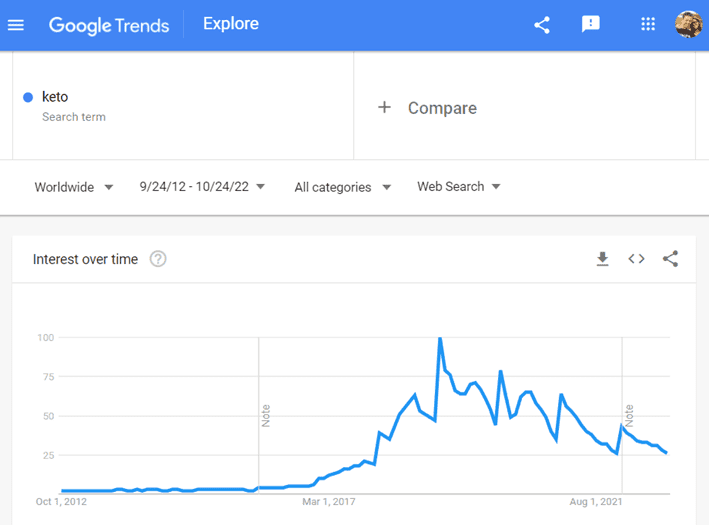

Many believe the simple solution is to cut carbs to decrease insulin and lose weight. This has been the dominant belief that has driven the keto movement.

Protein Leverage Hypothesis

In contrast, the Protein Leverage Hypothesis of Obesity explains that we become overweight because we continue to eat until we get enough of the nutrients our bodies need, particularly protein. In other words, we’ll overeat energy — from fat and carbs — if our food environment is low in protein. We become obese and insulin-resistant from overconsuming energy.

Our food system has become increasingly refined, processed, and inundated with more energy from refined sugars, grains, and industrial seed oils. Additionally, synthetic fertilisers, agricultural subsidies, and technological innovations regarding food production have made these foods both hyper-palatable and hyper-profitable.

Smart food manufacturers love to sell us the food we love to eat!

So, to reverse this trend, we must dial back energy from BOTH carbs and fat while prioritising protein. Interestingly, this doesn’t mean you have to increase your absolute protein intake (i.e., in grams) much, if at all. It doesn’t take a significant shift in protein % to increase satiety marginally and decrease overall energy intake. For more, check out this article on the Protein Leverage Hypothesis.

Aside from protein, our analysis suggests we also crave other nutrients—like vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids, and amino acids—in our food. Thus, we’ll be satisfied with fewer calories if we can pack more of all the nutrients we need into our food. For more detail on this, check out The Cheat Codes for Nutrition for Optimal Satiety and Health.

Carb-Insulin Hypothesis vs Protein Leverage Hypothesis

In an exciting juxtaposition, each model’s foremost proponents recently gave a 15-minute presentation to the Royal Society Scientific Meeting on the Causes of Obesity: Theories, Conjectures, and Evidence. For details, check out this video on Dr David Ludwig’s presentation on the Carb-Insulin Hypothesis (from 4:38), followed by Professor Stephen Simpson (from 37:03).

Why Low-Carb Works

I’m a fan of lower-carb diets—not to be mistaken for high-fat—particularly for people with dysregulated blood glucose levels. However, I don’t believe the magic simply comes from its ability to reduce glucose and insulin after you eat.

The real magic of lower-carb diets comes from their ability to move you away from the fat-and-carb combo foods that overdrive-drive your dopamine. The foods most people consider to be ‘bad carbs’—like cakes, chips, doughnuts, and pizza—are actually the magical low-protein, low-fibre combinations of fat and carbs.

These low-satiety foods allow us to fill our glucose and fat fuel tanks simultaneously and rapidly. Our bodies LOVE these foods, so we crave and eat more.

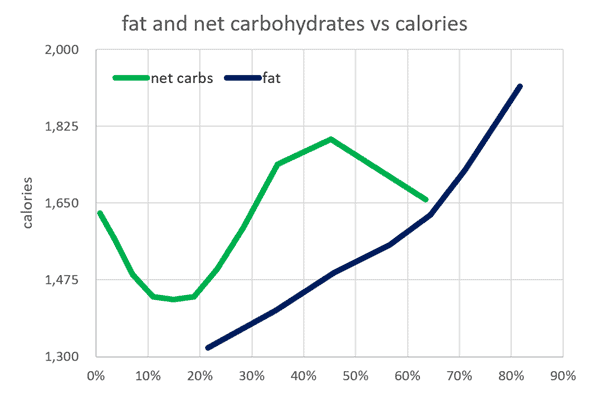

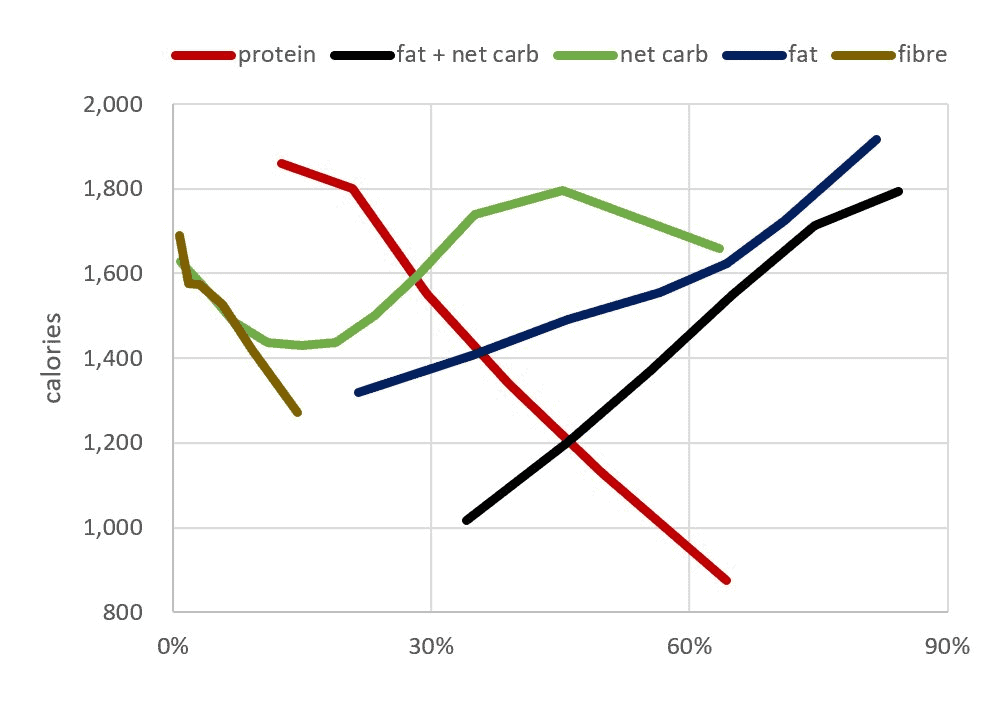

We created the chart below using our satiety analysis of one hundred and fifty thousand days of food logging data from forty-five thousand Nutrient Optimiser users. As we can see, we eat 23% fewer calories when we lower non-fibre carbs from 45% to 10-20%.

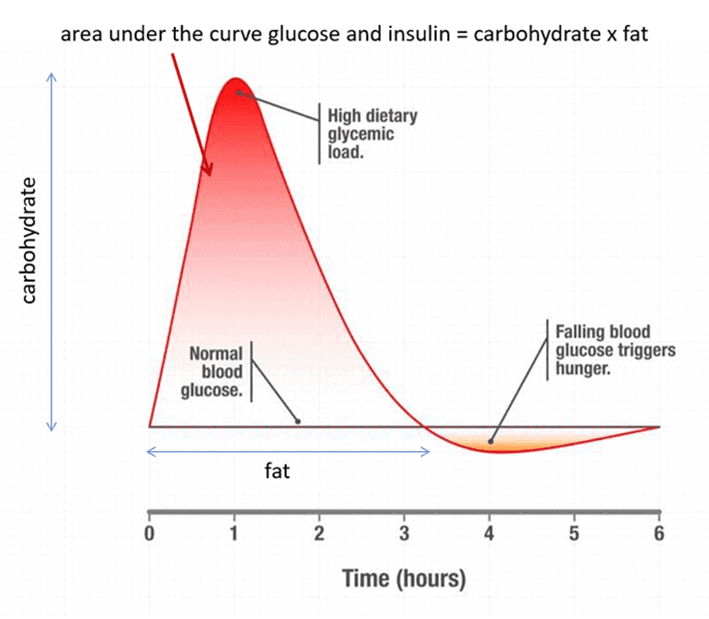

Additionally, reducing our carb consumption stabilises our blood glucose levels so we can get off the blood sugar rollercoaster and regain control of our appetite. The biggest problem with large intakes of high-glycemic carbs in the short term is when your glucose rapidly spikes and then crashes a few hours later.

When your glucose levels fall below your normal, your primitive ‘lizard brain’ takes over, and you eat anything and everything until you feel good and raise your blood glucose again!

An elegant study from the Zoe team with more than a thousand people wearing CGMs—Postprandial glycaemic dips predict appetite and energy intake in healthy individuals—showed that people who have the largest swings in glucose that tend to have the most dysregulated appetite and end up eating more at the next meal.

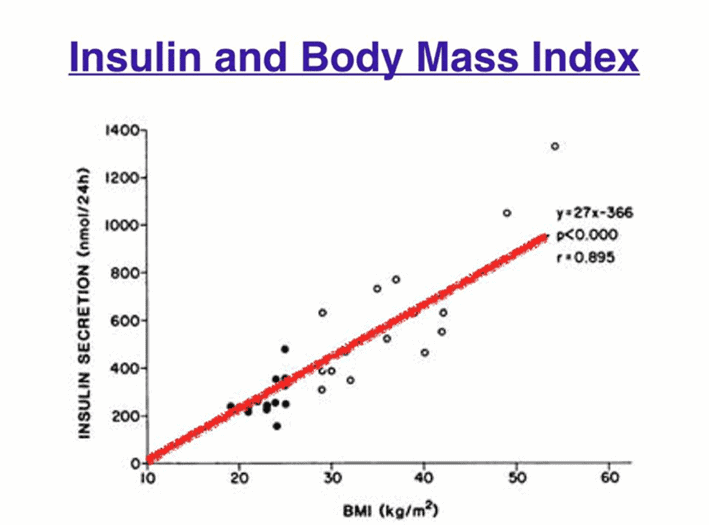

As this process continues, we eat more than we need to and gain weight. Because insulin works primarily as an anti-catabolic hormone that keeps us from using stored energy, we eventually need more insulin to store that fat.

Before too long, basal insulin levels creep up, and we become insulin resistant because we are getting fatter (not the reverse).

Basal vs Bolus Insulin

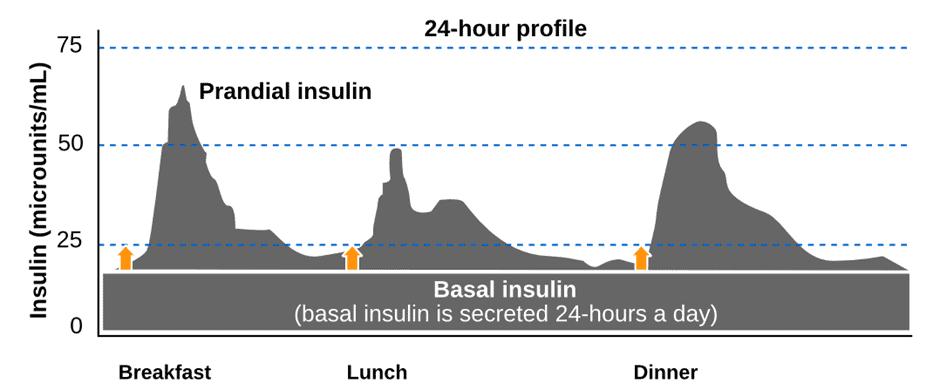

When discussing insulin, it’s important to differentiate between bolus and basal insulin.

- Your pancreas secretes bolus insulin in response to the food you eat, while

- Basal insulin is secreted by your pancreas 24/7, whether you eat or not, to regulate the release of stored energy in your bloodstream.

Because it’s easy to measure, bolus insulin usually gets most of the attention. The Food Insulin Index testing shows that carbs raise insulin the most over the first three hours. Protein and fat have a much smaller impact over a longer period of time.

But the rise in insulin after you eat is only half the story. Data from people with Type 1 Diabetes suggest that about half the insulin produced by the pancreas on a standard western diet is basal. If you reduce your carbs, you may end up with an 80:20 basal:bolus split.

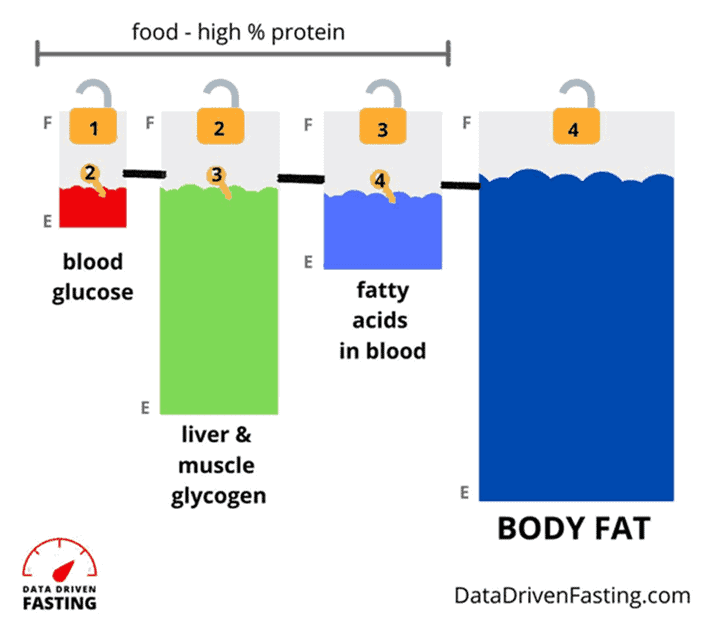

So if your carbs are already low, the next step to reduce your insulin levels and reverse your insulin resistance is to eat for greater satiety to enable you to reduce your excess body fat.

Someone who is obese and insulin resistant may have a fasting insulin of 30 uIU/mL. This basal insulin is required across the day just to hold the large amounts of stored energy (body fat and glycogen) in storage. Without the basal insulin, all of their stored energy would spew into their bloodstream like someone with uncontrolled Type 1 Diabetes.

Your body has plenty of capacity to store dietary fat as body fat, so we don’t see a large short-term insulin response to a high-fat meal. However, excess dietary fat can still contribute to body fat and thus increase your basal insulin. The bigger you are, the harder your pancreas will need to work to keep all that energy in storage.

The bottom line here is that:

- dietary fat can easily be stored as dietary fat, even though it doesn’t raise insulin much after you eat,

- excess stored energy is the root cause of insulin resistance, and

- simply ‘eating fat to satiety‘ in the mistaken belief that it does not affect your insulin may cause you to worsen the root cause of your insulin resistance.

Reducing Carbs is a Smart Place to Start

In Data-Driven Fasting and our Macros Masterclass, we suggest participants dial back their intake of refined and processed carbs if their glucose rises by more than 30 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) after they eat.

However, most people in our challenges already come from a lower-carb or keto background. Because they have been told that carbs and insulin work together as our mortal enemy, their progress stalls out because they often overconsume dietary fat.

The chart below shows the distribution of the rise in glucose after meals in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges. Only about 9% of participants find they need to dial back carbs to achieve healthy post-meal glucose levels.

A lot of my time each day is spent helping people understand that just because dietary fat does not raise glucose or insulin much over the short term, fat is not a ‘free food’ that they can eat to satiety.

In our Macros Masterclass, many people quickly realise how many extra calories come from fat when they start tracking their foods. Fat also contains little in the way of micronutrients—or your vitamins, minerals, and amino acids—so it isn’t very satiating.

Participants of our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges find that when they dial back their dietary fat, their glucose drops sooner, and they can eat a nourishing meal again sooner.

Fat Is NOT a Free Food!

Unfortunately, dietary fat is not a free food you can ‘eat to satiety’, as some have been led to believe. When we look at the relative satiety response of fat vs carbs, we see that reducing fat can influence satiety even more.

Lowering carbs while not fearing fat can be a great way to start your weight loss journey. However, if we believe carbs raise insulin and insulin makes us fat, it’s easy to give ourselves a free pass to fat and swap one pattern of disordered eating for another. Unfortunately, we can’t simply ‘hack’ our biology. Optimal never lies at extremes!

Excessive dietary fat consumption can lead to fat gain and high basal insulin levels. In fact, slamming fat in pursuit of high ketones and ‘eating fat to satiety’ can easily contribute to increased insulin resistance. Consuming more energy beyond Your Personal Fat Threshold will lead to metabolic disorder over time.

What’s the Solution

The Protein Leverage Hypothesis centres around the idea that we eat to get what we need from food, whether it be protein, the amino acids that makeup protein, or other vitamins, minerals, and essential fatty acids.

So, the elegant solution is to prioritise giving our bodies what it needs and reduce our energy intake if we are obese or insulin resistant.

The chart below shows the average satiety responses to all the macros and fibre alongside one another. Here, we can see that:

- Reducing either fat or carbs aligns with eating less;

- Reducing energy from fat and carbs results in an even more substantial reduction in calorie intake than if we were to reduce fat or carbs alone; and

- The inherent increase in protein %, or the per cent of total calories from protein, that results from reducing fat and carbs has the most significant impact on satiety.

When you give your body the protein and nutrients it needs with less energy, your appetite settles down.

This is theoretically simple but not necessarily easy in practice because you must fight against your natural urges for comforting energy-dense, low-protein carb-and-fat combo foods.

In nature, this macronutrient combination was only available in the months leading up to wintertime, which allowed us to pack on the pounds and make it through what could be a long winter. It’s hard to resist these foods when they surround us because we’re hard-wired to eat more of them when they’re available! Your life literally depends on it—or so your body thinks.

Your Personal Fat Threshold and Oxidative Priority

To tie this up, I want to touch on another theory I find extremely helpful for understanding insulin resistance and diabetes—Professor Roy Taylor’s Personal Fat Threshold Theory.

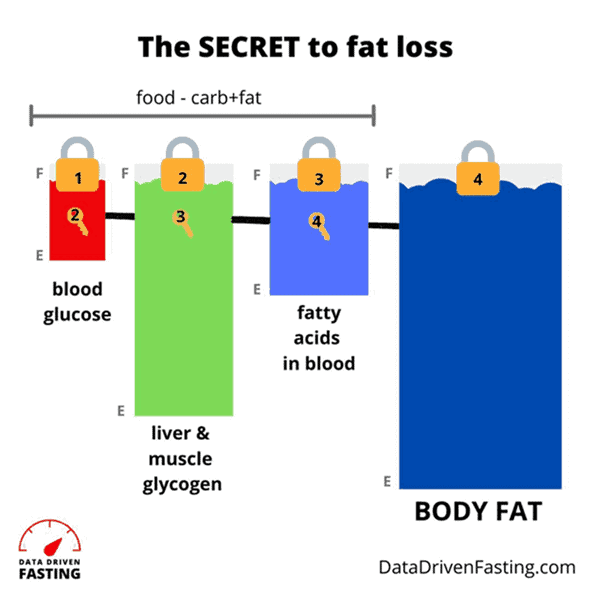

Your body has a large—but not infinite—capacity to store fat. Once your body fat capacity taps out, energy backs up in your system, which you see as high blood glucose. Essentially, you’ve over-fuelled your fat and carb fuel tanks, which you see on your glucometer.

Most of us walk around with all our fuel tanks full to the brim. Because of oxidative priority, we must deplete our glucose before we can unlock our stored body fat.

Dialling back carbs allows you to manage symptoms of insulin resistance, like high blood glucose. But it doesn’t address the root cause—energy toxicity—that stems from exceptionally high body fat levels, particularly if we keep overfilling our fat fuel tank.

Everyone has a different body fat threshold, which explains why people become insulin resistant at different weights.

If your goal is to burn and lose body fat, it is still critical to dial back dietary fat. If we can scale back our intake of carbs and a little fat while prioritising protein and nutrients to maximise satiety, we can draw down our body fat and address energy toxicity, the root cause of insulin resistance. Eventually, your pancreas won’t need to work as hard to keep all that body fat locked away in storage.

For more info, see:

- Oxidative Priority: The Key to Unlocking Your Body Fat Stores

- Personal Fat Threshold Model of Insulin Resistance, Diabetes and Obesity

What to Eat to Increase Satiety and Reverse Insulin Resistance

So, by now, you probably want to know what to eat.

There’s no magical protein leverage diet. It’s simply a matter of giving your body the protein and nutrients it needs with less energy.

With all the nutrients and less energy, your cravings will settle so you can draw down on the stored energy in your body.

Foods

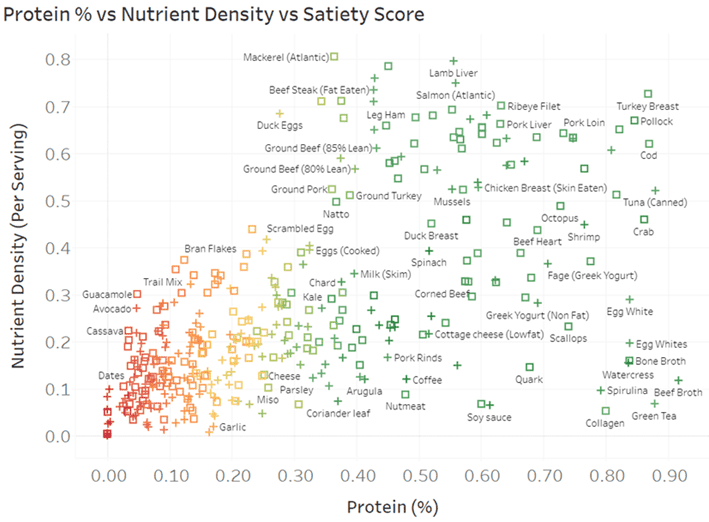

The chart below shows how various foods rank in terms of protein % vs nutrient density vs satiety.

- To increase your protein %, choose recipes towards the right.

- To increase nutrient density, choose recipes towards the top.

- For greater satiety, avoid the red recipes and focus on the green ones.

You can dive into the detail with our interactive Tableuea chart here or access our suite of free food lists.

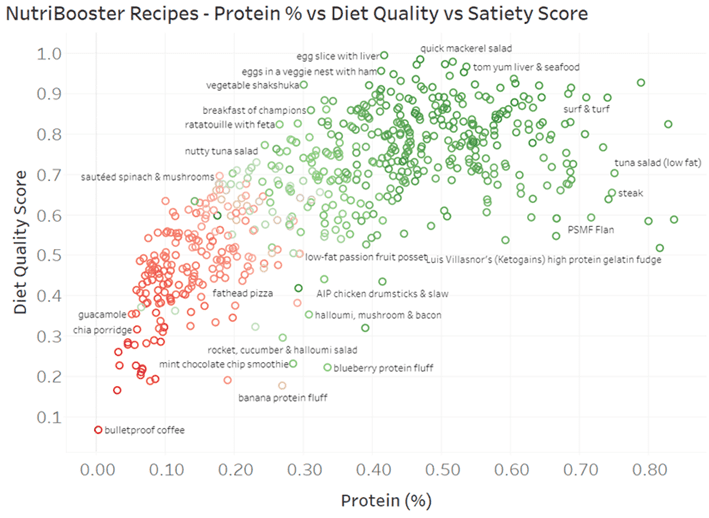

Meals

Rather than just foods, the chart below shows six hundred of our NutriBooster recipes, graphed in terms of protein % vs nutrient density vs satiety. You can also dive into all the details in the Tableau chart here.

Summary

- The carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity can be helpful, but it only addresses half of the problem. Protein leverage focuses on dialling back energy from carbs AND fat while prioritising the protein and nutrients your body requires.

- While reducing carbohydrates can be helpful, particularly if your blood glucose is dysregulated, it’s only part of the solution.

- Even though dietary fat raises insulin and glucose less over the short term, it can still lead to body fat gain, which increases insulin resistance and basal insulin requirements over the longer term.

- Once you’ve dialled back your carbs to manage blood sugars and the short-term bolus insulin response to food, the next logical step is to target your basal insulin.

- Prioritising protein and nutrients while dialling back fat and carbs is the most effective way to increase satiety and lose fat and thus addresses the root cause of insulin resistance: energy toxicity.

More

- The Carb-Insulin Hypothesis vs Protein Leverage Hypothesis of Obesity

- Personal Fat Threshold Model of Insulin Resistance, Diabetes and Obesity vs the Carbohydrate Insulin Model

- Does Protein Spike Insulin (and Does It Matter)?

- The Protein Leverage Hypothesis

- Highest Satiety Index Meals and Recipes

- High Satiety Index Foods: Which Ones Will Keep You Full with Fewer Calories?

- What Does Insulin Do in Your Body?

- What Is Insulin Resistance (and How to Reverse It)?

Question: where does fiber fit into all of this? Yes, it’s carbs, but undigestible net zero ones.

Whether you’ve got energy going in as fat/carbs, or energy going in as protein/gluconeogenesis, how is one lose supposed to lose weight, besides a never-ending fast? People can’t live while on a never-ending fast–ask a staunch Breatharian if you can find one still living.

When faced with the dilemma of physical disability to the point where exercise is impossible (such as various diseases that restrict one to a wheelchair, like the late Stephen Hawking), how does one go about losing weight besides fasting or ingesting fiber just to maintain existence? Also, how does one maintain adequate nutrition when facing this circumstance, other than IV nutrition?

naturally, occurring fibre is a marker of lower processing. the energy in these foods tends to be more slowly absorbed, and some passes on through. but I don’t think it’s just the fibre, but the nutrients that tend to come with fibre that also satisfy cravings (e.g. manganese, copper, iron, C, E, K1, folate). foods with more fibre tend to be more beneficial, but not as much as protein. https://optimisingnutrition.com/dietary-fibre/#h-higher-fibre-foods-tend-to-be-more-nutritious

but the bottom line of this article is that you just need to prioritise protein (and fibre) and dial back fat and carbs a little. it doesn’t take a radical shift.

Just found this: Go pound sand

https://www.sciencealert.com/purified-sand-particles-have-anti-obesity-effects-scientists-confirm

maybe the next fad diet will be eating the sand at the beach or the desert?

I understand that we need to lower fat and carbs. If I’m eating chicken breast, lean Turkey, egg whites, fat free cheese, cottage cheese, and Canadian bacon- with spring mix salad, broccoli, cauliflower, green beans, salsa- which I would find not too hard- is this too low in fat? And are we supposed to count calories? I am 47 years old, 5’3 and 159lbs. I was doing some fasting and had mild success but nothing too exciting. Should I still be fasting? I am confused about how much protein I should be aiming for. I can’t exercise much besides walking and light weights due to ehlers danlos syndrome. I’m very much enjoying reading all the articles and the book! Thank you 🙂

So glad you’re enjoying the articles. Thank you!

Simply limiting calories rarely ends well, but tracking can be useful to dial in your macros to improve satiety.

Check out the links at the bottom of this article to learn what we do in the Macros Masterclass. https://optimisingnutrition.com/macros-masterclass/