When it comes to dietary recommendations, fiber often takes center stage as a crucial part of our diet.

But is it an essential nutrient or just a well-intentioned myth? In a realm filled with diverse dietary advice, the role of fiber has left many individuals puzzled about its actual importance for well-being.

Dive into an enlightening exploration as we sift through the scientific intricacies of dietary fiber, examining its potential benefits, its impact on gut health, blood sugar levels, and beyond.

With a blend of science-backed insights and myth-busting facts, this article aims to provide a clearer understanding of fiber’s place in our nutritional landscape.

- What Is Dietary Fibre?

- What Are the Main Types of Fibre?

- Other Types of Fibre

- Does Fibre Help You Poop?

- Can Dietary Fibre Help Your Gut Health?

- Does Fibre Lower Blood Sugar?

- Can Eating More Fibre Lower Cholesterol or Lower My Risk of Other Diseases?

- Will Fibre Help You Eat Less?

- The Fibre:Carbohydrate Ratio

- Fibre vs Net Carbs

- Total Carbs vs Net Carbs

- How Much Fibre Should I Consume?

- Higher Fibre Foods Tend to Be More Nutritious

- What Nutrients Do High Fibre foods Provide?

- What Foods Contain Fibre AND Nutrients?

What Is Dietary Fibre?

Before we get started, what is dietary fibre?

Scientifically, dietary fibre refers to a non-starchy chain of polysaccharides and lignins that cannot be broken down or absorbed by the human digestive tract. Because of its chemical structure, fibre can swell, retain water and fat, and serve as a prebiotic and antioxidant.

What Are the Main Types of Fibre?

While we often refer to all fibres as fibre, there are two main types:

- soluble, and

- insoluble.

Soluble Fibre

‘Soluble’ means it can be dissolved in water.

Soluble fibre is a viscous fibre that dissolves and expands in water. This fibre is later broken down in the large intestine and is readily found in foods like oats, peas, beans, apples, oranges, carrots, barley, psyllium, and pears.

Soluble fibre is often referred to as the ‘heart-healthy’ fibre for its cholesterol-lowering and detoxifying abilities. Additionally, it slows gastrointestinal movement, which gives you the feeling of staying full for longer and blunts the rate at which glucose is absorbed into your bloodstream.

Insoluble Fibre

Aside from soluble fibre, we also have insoluble fibre. This is the type of fibre we associate with ‘roughage’. You can find insoluble fibre in vegetables—especially green and leafy ones—nuts, whole grains, and some fruits.

In contrast to soluble fibre, insoluble fibre does not dissolve when mixed with digestive fluids and remains relatively unchanged as it passes through your system. This is because humans do not have the enzymes to break down the plant fibres it contains. However, this type of fibre is excellent for adding stool bulk and making your bowels move smoothly.

Other Types of Fibre

Aside from these two main fibre categories, there are also different kinds of fibre with varying health benefits.

Beta-Glucan

Beta-glucan is a kind of soluble fibre with antioxidant properties. It also increases and regulates immune function, lowers cholesterol, and improves blood glucose control. You can find it in whole grains like oats, barley, sorghum, and rye.

Fructans

Fructans are tiny chains of fructose molecules found readily in different fruits and grains. They can be helpful prebiotics and can reduce certain types of diarrheas.

The two main types of fructans are inulin and oligofructose, which are found readily in watermelon, onions, shallots, leeks, asparagus, and artichokes.

For someone with IBS or IBD, fructans can cause digestive upset as they belong to the category of foods known as FODMAPs.

Lignins

Lignins are a chain of polymers that help make up the cell walls of plants. You can find them in whole grains, legumes, fibrous vegetables, fruits like avocados and unripe bananas, nuts, and seeds. Lignins are known to have disease-preventing, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties.

Cellulose

Like lignins, cellulose is an insoluble fibre that helps give a plant structure. It is known for helping move food through your digestive system and keeping your bowel movements regular. For this reason, it’s been linked to reducing the risk of developing constipation-related diseases like diverticulosis and GI cancers.

Pectins

Pectins are soluble fibre found in apples, citrus fruits, pears, grapes, and some vegetables. It’s used in food manufacture as a gelling agent to thicken jams and jellies, and it’s sold as a popular health supplement (i.e., modified citrus pectin) that has been shown to have anti-cancer and detoxifying properties.

Resistant Starch

While resistant starch technically isn’t a fibre, they’re worth mentioning.

Resistant starch is a type of starch that resists digestion, similar to fibre. It forms when certain types of starch are heated and cooled, and it serves as a prebiotic. Additionally, the rate at which the sugars are broken down in resistant starch is slower, meaning these ‘starchy’ foods might have a less substantial effect on blood glucose if you let them cool first.

What’s cool is that if you heat them up and let them cool multiple times, you will form more resistant starch!

Foods high in resistant starch include green bananas, plantains, legumes, oats, white and sweet potatoes, and cashews.

Does Fibre Help You Poop?

Fibre absorbs water and adds bulk to your stool. Subsequently, consuming dietary fibre can increase your bowel movements’ weight and size, making them softer and easier to pass. It can also allow you to pass stools more frequently.

If you frequently deal with loose or watery stools—commonly reported on a zero-carb diet—fibre can help by absorbing some of the water.

Fibre is a critical component of a healthy bowel movement. However, your water, potassium, sodium, calcium, magnesium, and fat intakes can also influence how often—and how easily—you poop!

If you’re hitting your mineral, nutrient and water goals and still experience constipation or diarrhea, it might be worthwhile investigating your microbiome.

Can Dietary Fibre Help Your Gut Health?

Dietary fibre is also touted as beneficial for its pro #guthealth benefits. However, this is a bit more complex, and it depends on the health of the person eating it.

Because dietary fibre is undigestible, it is a prebiotic or substance that feeds the bacteria in your intestines. This is great for someone with a healthy gut as it gives good bacteria fuel to produce substances like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate that nurture the colonocytes lining your intestines.

However, if you have an unhealthy microbiome and suffer from a condition like Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), Inflammatory Bowel Disorder (IBD), bacterial overgrowth, or dysbiosis, you might feel awful consuming more fibre. This is because you’re essentially feeding this bacterial imbalance. Often when these chronic issues resolve, fibre intolerance goes away.

Some nutrition groups demonise fibre for some of the symptoms it causes when it is not tolerated. However, it may not be the fibre is not the problem—it is your microbiome. Once you get your gut healthy, fibre should be your friend again!

Gut health is a complex, controversial rabbit hole. But feeding a healthy gut is similar to feeding a healthy human. Our modern diet tends to be packed with energy-dense, ultra-processed foods that create rapid growth in us and our microbiome. Once you prioritise a variety of nutrient-dense, higher-satiety foods, you will also create a more balanced bacterial profile in your gut.

Does Fibre Lower Blood Sugar?

In contrast to other carbohydrates like sugar or starch, we cannot break fibre down.

Additionally, fibre slows transit time through the gastrointestinal system. As a result of both of these factors, consuming more fibre can delay glucose uptake, which can minimise blood glucose spikes and cravings that tend to ensue after we eat a lot of nutrient-poor, low-fibre carbs.

Our food insulin index analysis shows that dietary fibre has a negligible impact on blood glucose and insulin.

Can Eating More Fibre Lower Cholesterol or Lower My Risk of Other Diseases?

Exogenous (from the outside environment) and endogenous (from your body) toxins have been linked to diseases like cancer, diabetes, heart disease, autoimmunity, autism, and neurodegenerative conditions.

When these substances make it into your body, they undergo processing in your liver. From there, they are released into bile, where they find their way out of your body through your stools—that is, if you’re pooping!

As we mentioned in earlier sections, soluble ‘viscous’ fibre is a gel-like substance that swells in the digestive tract. Because of its absorbent and absorptive properties, fibre is known to grab hold of compounds in the digestive tract, like cholesterol, bile acids, and toxins in bile, so they make their way out. This is where fibre gets labels like ‘hearty-healthy’ and ‘reduces cancer risk’.

At this point, it’s worth noting that most of the cholesterol in your blood is produced in your liver. Cholesterol was removed from the 2015 US Dietary Guidelines as a nutrient of concern because it was found there is no link between dietary cholesterol and heart disease. Our satiety analysis has found that nutritious foods that naturally contain more cholesterol tend to be more satiating. For more on this, see:

- Cholesterol: When to Worry and What to Do About It, and

- Dietary Cholesterol and Blood Cholesterol: Are They Related?

- The Cheat Codes for Nutrition for Optimal Satiety and Health.

In addition, insoluble ‘non-viscous’ fibre helps to bulk up your stools and keep your bowels moving and grooving. If you are not regularly eliminating waste by pooping, the toxins in your poop—and the junk in it—can build up and recirculate inside of you.

The relationship between more fibre and a lowered risk of many chronic illnesses is multifactorial. However, some of the main components are fibre’s ability to stabilise blood sugars, remove toxins, and nurture the health of the cells lining your gastrointestinal tract.

Will Fibre Help You Eat Less?

Fibrous foods are hard to overeat. This is partially due to its absorbent properties; when fibre makes contact with your digestive juices, it swells and increases in volume.

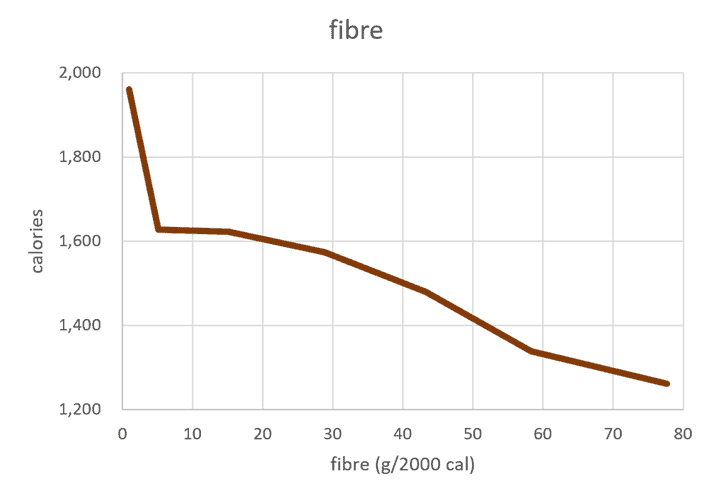

The following chart shows the average satiety response to fibre using 106,106 days of data from our Optimisers. Here, we can see that:

- A slight increase in fibre consumption from zero to five grams of fibre per day aligns with a significant calorie drop. So, some fibre tends to be more satiating than no fibre.

- People consuming more fibre tend to eat a substantial 39% fewer calories.

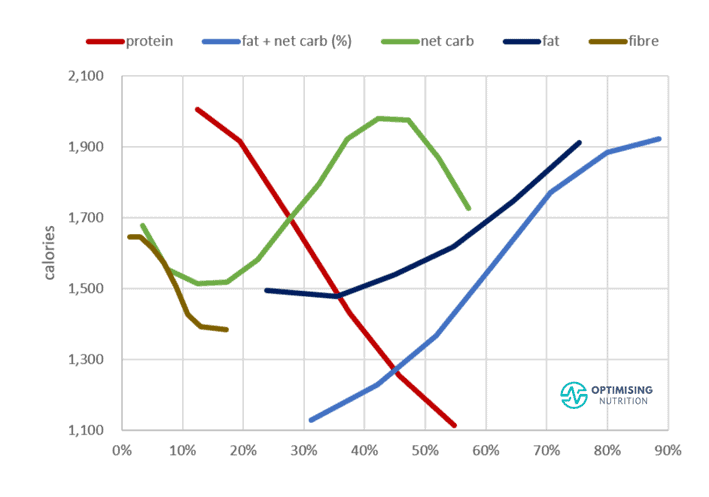

The table below shows the results from our analysis of 111,897 days of Optimiser data. Here, we see that while moving from low to high protein per cent—or per cent of total calories from protein (protein %)—impacts satiety the most, fibre ranks at #3 after potassium.

| Nutrient | P-value | 15th | 85th | Calories | % |

| protein | 0 | 19% | 44% | -486 | -31.6% |

| potassium | 2.18E-38 | 1931 | 5915 | -72 | -4.7% |

| fibre | 7.96E-48 | 11 | 44 | -70 | -4.5% |

| sodium | 1.14E-28 | 1480 | 5076 | -41 | -2.7% |

| calcium | 1.69E-17 | 469 | 1869 | -40 | -2.6% |

| pantothenic acid (B5) | 0.006 | 4 | 15 | -18 | -1.1% |

| folate | 0.22 | 167 | 956 | -7 | -0.4% |

| total | -47.6% |

For more details on this analysis, see The Cheat Codes for Nutrition for Optimal Satiety and Health.

That said, people consuming more fibre tend to eat 4.5% fewer calories when all the other factors that positively influence satiety are considered.

The chart below shows our satiety response to fibre, protein, fat, and non-fibre carbohydrates. Although a higher fibre intake aligns with eating less, the impact is small compared to protein %. As you will see, adequate fibre tends to come along for the ride when we prioritise foods with a higher nutrient density.

For more details on this analysis, see The Cheat Codes for Nutrition for Optimal Satiety and Health.

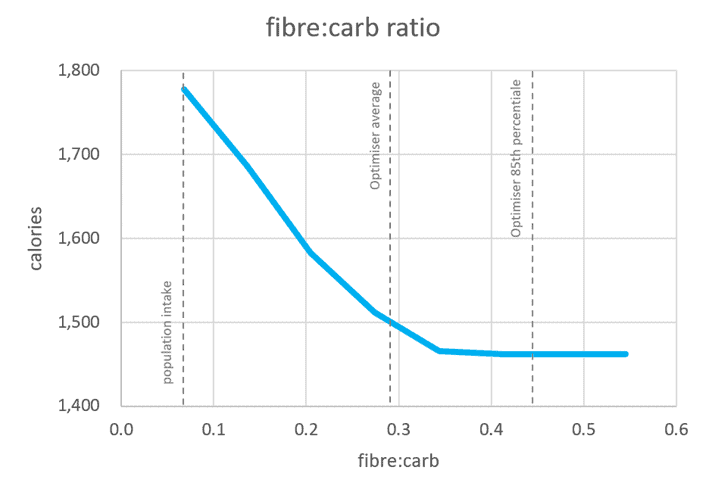

The Fibre:Carbohydrate Ratio

If you’ve read our article on protein and protein %, you’d know satiety that it’s not about simply eating more protein.

Interestingly, we see a similar trend in the data when it comes to fibre.

If you consume carbohydrates, it’s more important to ensure you’re eating more fibrous carbohydrates and less starchy, processed ones that consist of sugars and refined flour.

The chart below shows that we eat 20% fewer calories when more of our total carbohydrates are fibrous. But you’re not going to get a lot of extra benefit from increasing your fibre:carb ratio beyond 0.3.

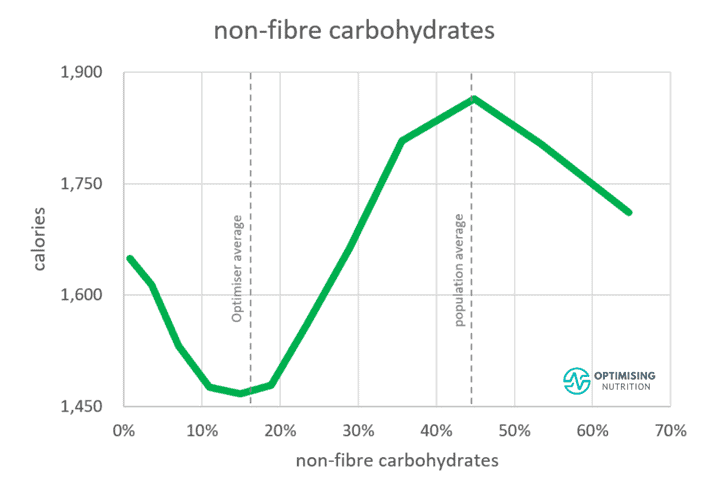

Fibre vs Net Carbs

Because your body cannot break fibre down into usable fuel unless you’re using something like digestive enzymes, it’s often better to think in terms of net carbs. Net carbohydrates are simply total carbohydrates minus fibre and sugar alcohols.

Net Carbs = Total Carbohydrates – (Carbs from Fibre + Carbs from Sugar Alcohols)

There’s not much point for most people trying to avoid the carbs in your lettuce, asparagus, or broccoli for the sake of carbs. Not only is that fibre beneficial for satiety, but it also accompanies all the other micronutrients that make those foods nutrient-dense and valuable. Additionally, it does not significantly affect blood glucose levels.

The chart below shows our satiety response to net carbohydrates. As you can see, the maximum calorie intake corresponds to 45% non-fibre carbohydrates, and the minimum calorie intake aligns with 10-20% non-fibre carbohydrates.

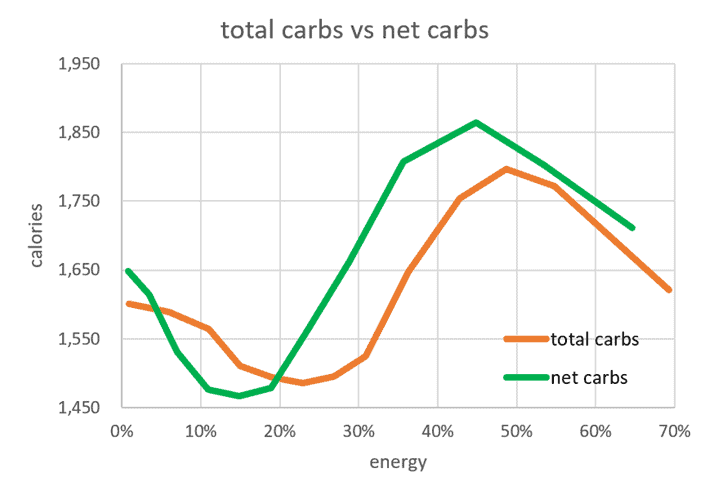

Total Carbs vs Net Carbs

The following chart shows our calorie consumption and how it corresponds to varying intakes of total carbs and net carbs together. Here, we see a more significant 25% reduction in energy when we focus on net carbs instead of only 19% if we consider total carbohydrates.

So, if you’re managing your carbs to stabilise blood sugars or dialling in your macros to maximise satiety, it’s more beneficial to focus on net carbs over total carbs.

How Much Fibre Should I Consume?

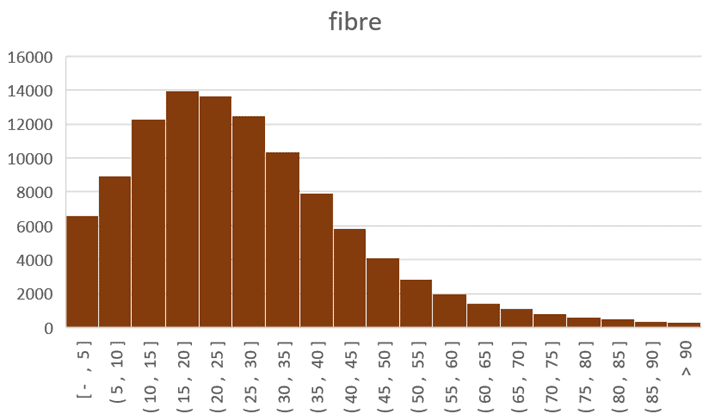

Everyone wants a specific target that they should target. However, your gut microbiome and fibre demands are as unique as your fingerprint, so the fibre intake that’s best for you may vary dramatically from the person next to you. Instead of giving you a fixed intake, I listed some stats from our Optimiser data below:

- The average fibre intake amongst our Optimisers is 24 grams per 2000 calories.

- The 85th percentile fibre intake of our Optimiser population is 44 grams per 2000 calories.

- The 15th percentile Optimiser intake is 10 grams per 2000 calories.

The following distribution chart below shows our Optimisers’ entire range of fibre intakes per 2000 calories.

If you’re looking for a ballpark target, the table below shows some ranges for low, high and average depending on your calorie intake based on our Optimiser data. However, as you will see below, if you are prioritising your priority nutrients from whole foods, you’ll be getting plenty of fibre.

| Calories | Low | Average | High |

| 1000 | 5.0 | 12 | 22 |

| 1500 | 7.5 | 18 | 33 |

| 2000 | 10 | 24 | 44 |

| 2500 | 12.5 | 30 | 55 |

| 3000 | 15 | 36 | 66 |

If you’re interested in identifying your priority nutrients and the foods and meals that contain them, you can take our 7-Day Nutrient Clarity Challenge here.

Higher Fibre Foods Tend to Be More Nutritious

While fibre is not an essential nutrient, consuming more dietary fibre is correlated with higher intakes of micronutrients found readily in fibre-rich plant foods, like:

- Manganese,

- Copper,

- Iron,

- Vitamin C,

- Vitamin E,

- Vitamin K1,

- Folate,

- Potassium,

- Calcium, and

- Magnesium.

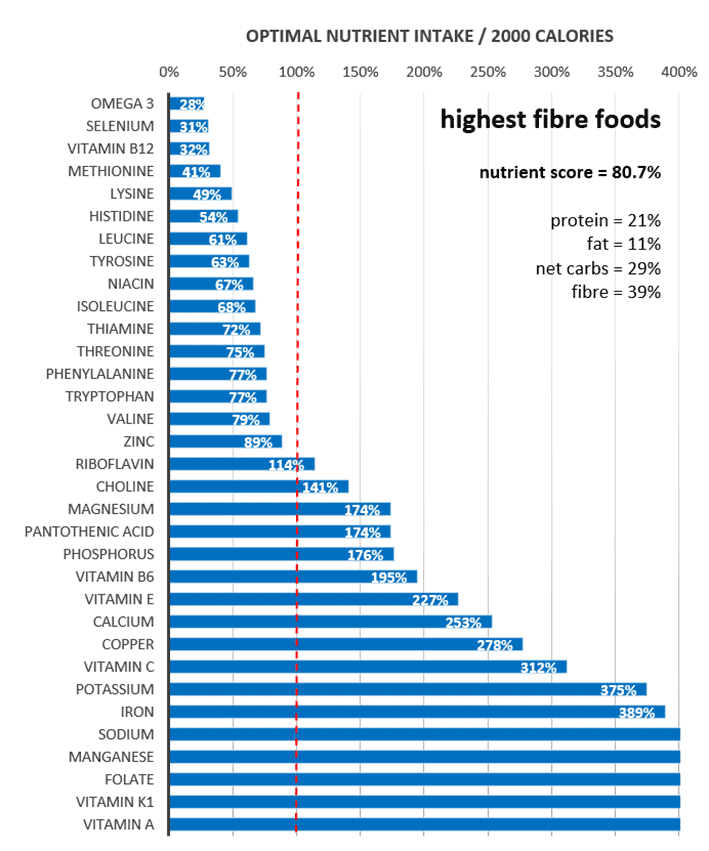

What Nutrients Do High Fibre foods Provide?

The micronutrient fingerprint below shows the nutrients found in the highest-fibre foods. Towards the bottom, you can see the most fibre-rich foods are packed with vitamin A, vitamin K1, folate, manganese, and a massive 39% fibre.

But towards the top, you can see that it’s challenging to come by critical nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids, selenium, B12, and most amino acids if you simply focus on fibre as your main priority.

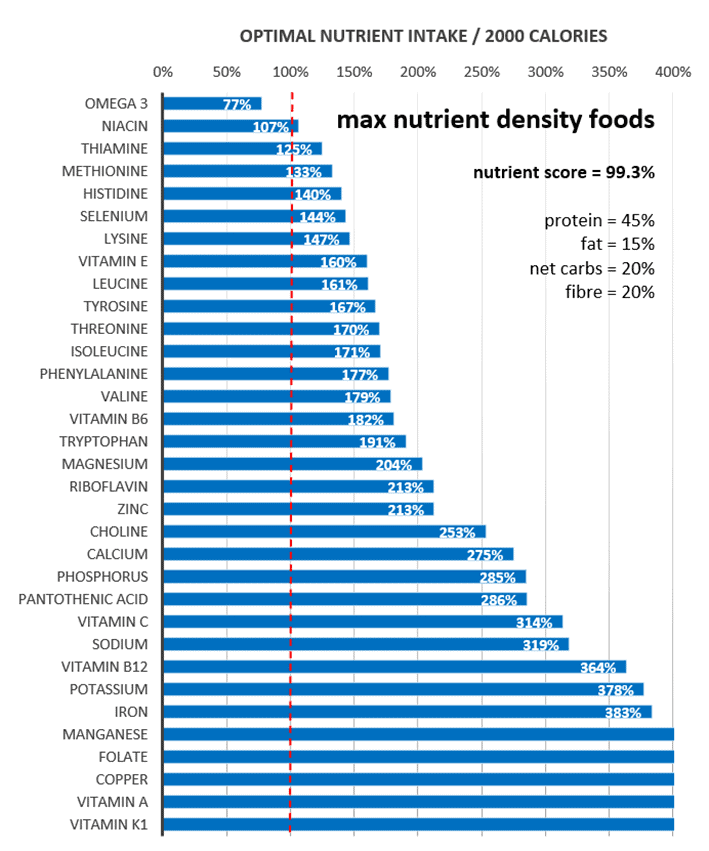

If we switch up our priority to the most nutrient-dense foods, the chart below shows what our nutrient profile would look like. When you focus on nutrient density, you’ll inherently get plenty of fibre (20%) from the nutrient-dense fibrous vegetables you will consume, AND a great complement of ALL the essential nutrients.

What Foods Contain Fibre AND Nutrients?

To help you up your fibre and nutrient density game, the chart below illustrates a range of foods in terms of fibre vs nutrient density. Foods towards the right contain more fibre per calorie.

The colours are based on our Satiety Index Score. The foods shown in red are easier to overconsume, while those in green are more satiating per calorie.

To dive into this data in more detail, check out the interactive Tableau version here.

Nutrient-dense high-fibre foods

Towards the top right corner, we can see there is a wide range of nutrient-dense, low-calorie, high-fibre foods like:

- broccoli,

- spinach,

- nori,

- endive,

- basil,

- wombok,

- collards,

- escarole, and

- celery.

It’s worth noting that these foods are ones that we typically eat in small quantities, at least in terms of the nutrients they provide.

Nutrient-dense low-fibre foods

But if we look towards the top left of the detailed version of the chart, we can see there is an array of nutrient-dense, high-satiety foods that contain no fibre, like:

- liver

- crab,

- kidney,

- shrimp, and

- caviar.

Foods like these are nutritious and satiating, even though they don’t contain fibre.

If you want some inspiration for more nutrient-dense foods and meals tailored to your goals and preferences, check out our full suite of optimised food lists and NutriBooster recipes here.

Summary

- Fibre is not an essential nutrient.

- There are two types of fibre: soluble ‘viscous’ and insoluble ‘non-viscous’.

- Viscous fibre helps trap wastes in the stool. Non-viscous fibre adds stool bulk and prevents constipation and diarrhea. The two together give fibre its detoxifying, ‘heart-healthy’, ‘anti-cancer’ properties.

- Fibre is satiating, but not as much as a higher protein %.

- Fibre has a negligible impact on blood glucose and insulin. So, if you’re managing your carbs, it’s better to track net carbs, which also aligns with our satiety response to food.

- Nutrient-dense plant-based foods contain fibre and other essential nutrients like manganese, copper, iron, vitamin C, vitamin E and potassium.

- You’ll get plenty of fibre if you chase the essential nutrients from whole food.

AMDR series

- Protein – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR)

- Carbohydrates – The Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR)

- Fat – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR)

- The “Acceptable” Macronutrient Ranges (AMDRs) for Protein, Fat and Carbs: A Data-Driven Review

- Dietary Fibre: How Much Do You Need?

- Low Carb vs LowFat: What’s Best for Weight Loss, Satiety, Nutrient Density, and Long-Term Adherence?

- High Protein vs High Fat: What’s Ideal for YOU?