Prepare to uncover the hidden secrets of protein and its dance with insulin!

We all know that carbohydrates send insulin levels on a rollercoaster ride. But here’s the curveball: dietary protein has its own ticket to the insulin party!

Here’s where it gets interesting: High insulin levels have been linked to metabolic mayhem, sparking worries about the health impacts of consuming “too much protein.” Some fear it might pack on the pounds or even shorten their lifespan.

But hold on to your dumbbells because, on the flip side, the world of bodybuilders is all about whey protein shakes strategically designed to give insulin a kickstart. Why, you ask? To supercharge muscle growth and slam the brakes on muscle breakdown!

Now, you’re probably wondering, “What’s the deal? How do we find the sweet spot between these contrasting views? Is protein our ally or adversary when it comes to insulin?”

Well, it’s time to cut through the confusion and get some answers! In this article, we’re taking the plunge into the intricate relationship between protein and insulin. We’ll lay it all out so you can decide whether or not to raise an eyebrow of concern.

How Does Protein Impact Insulin?

Fortunately, we have some robust data to help us understand the insulin response to protein.

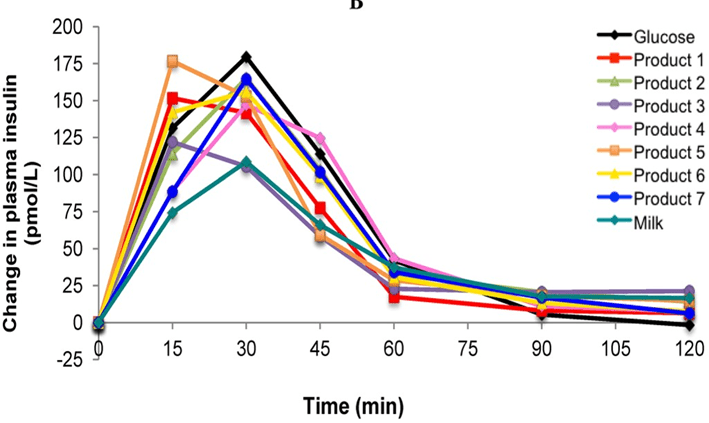

The 1997 study, An insulin index of foods: the insulin demand generated by 1000-kJ portions of common foods, measured the change in insulin levels above baseline in participants over three hours after consuming 38 popular foods.

The figure below shows the results of a few of these tests, with insulin measurements taken every 15 minutes. The Food Insulin Index is calculated based on the area under the insulin response curve.

While those tests measure the insulin response to carbohydrates well, they likely don’t capture the complete insulin response to protein or fat because it occurs over a longer timeframe.

Notice how the insulin response to pure glucose (black line) rises quickly but returns to baseline at three hours. Meanwhile, milk (aqua line) has a smaller insulin response over the short term but remains elevated after three hours.

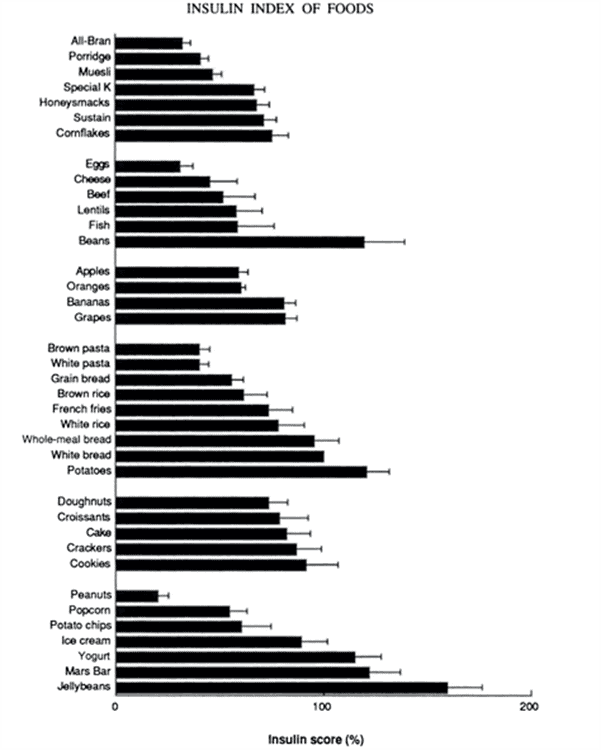

The figure below summarises the results of the original Food Insulin Index study. White bread was given a score of 100%, and all foods were measured relative to this. Jellybeans elicited the largest insulin response, while the insulin response to higher-fat foods like eggs and peanuts was much lower.

Unfortunately, 38 foods don’t clarify where everything else in our modern food environment stands. However, the insulin response has been tested for more foods using the same protocol since this initial study. We now have food insulin index data for 120 foods (document in the PhD thesis, Clinical Application of the Food Insulin Index to Diabetes Mellitus, Bell, 2014).

We ran a multivariate analysis of the complete data set and found the following:

- protein elicits 46% of the insulin response that carbohydrates do;

- fibre in food raises insulin by only 22% relative to non-fibre carbohydrates; and

- on a calorie-for-calorie basis, fat appears to raise insulin by about 15% relative to carbohydrates over the first three hours.

Based on this analysis, we can now calculate the food insulin index response to any food. The chart below shows carbohydrate (%) vs calculated food insulin index for a range of popular foods. You can dive into all the detail of this chart in the interactive Tableau version here.

If you’re wondering about the colour coding, it’s based on our food satiety index. In short,

- the foods shown in green contain the most protein and are thus relatively harder to overeat, while

- foods in red contain less protein and more fat and carbs, making them generally easier to overconsume.

Overall, we can see that the insulin response to the food we eat is heavily influenced by its carbohydrate content. However, when we look to the left of the chart, we see that many low-carbohydrate, high-protein, high-satiety foods also provoke a significant insulin response in the first three hours.

To summarise, all food elicits an insulin response, including protein and fat—not just carbohydrates!

The Lowdown on Protein and Insulin

So, what do we make of the fact that protein raises insulin?

Is it a problem?

Should we be concerned?

To answer this, we need to understand what insulin does in our bodies.

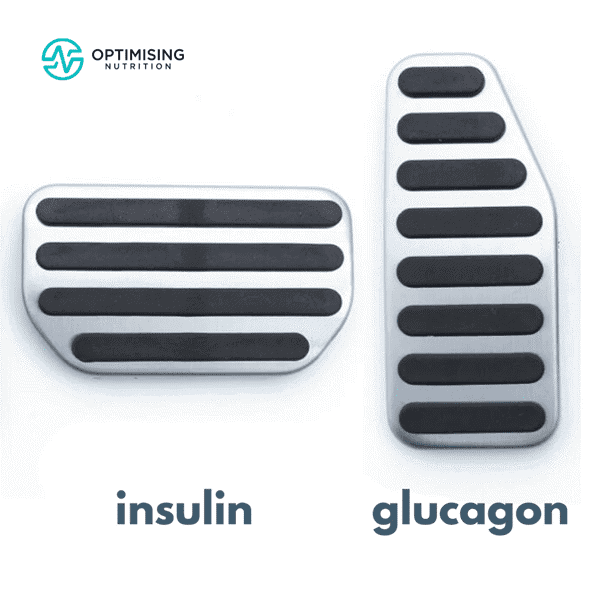

While most people know insulin as the anabolic hormone that forces glucose into cells, it can be more helpful to think of insulin as an anti-catabolic hormone.

In summary,

- We can liken insulin to a brake pedal that slows the release of stored energy into your bloodstream via your liver if you already have plenty of energy in your bloodstream.

- Meanwhile, glucagon is the antagonistic hormone to insulin or the ‘accelerator’ that prompts your liver to release stored energy when your blood sugar is low.

If your blood glucose levels rise too high, say above 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) or so, your pancreas will ramp up insulin production to push glucose out of your bloodstream and into storage. But in someone lean and metabolically healthy, insulin levels are low most of the time, and the body can use glucose without insulin via non-insulin-mediated glucose uptake.

For more info on insulin, check out:

Most of the insulin produced by your pancreas works to hold your energy reserves in storage, especially when you’ve eaten recently. So, depending on the amount of energy you have stored as body fat, liver and muscle glycogen, and blood lipids, your body may have more or less energy that needs to be held back by insulin.

Insulin slows the release of stored energy from the liver while energy is coming in via your mouth. As an extreme example, without insulin, someone with uncontrolled Type-1 Diabetes would essentially disintegrate as their stored energy flows into their bloodstream. Their body would plunge into uncontrolled catabolism. Eventually, they would be unable to inhibit the breakdown of their organs, muscles, bone, fat, and other tissues.

From people with Type-1 Diabetes, we also know that 50 to 80% of someone’s daily insulin is basal insulin or the insulin produced in between and away from meals. Thus, most of your daily insulin requirement is unrelated to your food intake.

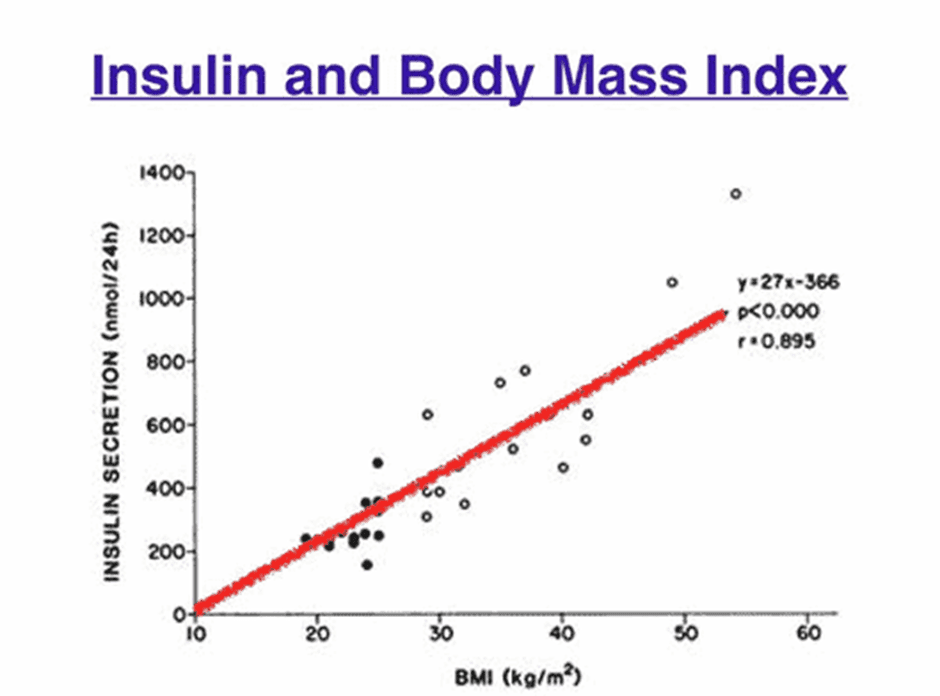

The figure below shows how the insulin secreted across the day is proportional to your BMI. So, although lowering carbohydrates will help reduce the insulin your pancreas needs to produce, the most effective way to lower insulin across the whole day—not just after meals— is to lower your body fat to healthy levels. This includes prioritising—and not avoiding—protein to increase satiety and build lean body mass.

Protein and Satiety

We know from the Protein Leverage Hypothesis and our own satiety analysis that protein is the most satiating macronutrient. Protein keeps you full and satiated with fewer calories, so you can eat less and lose weight over the long term.

As shown in the figure below, we consume less energy when dialling our protein % by reducing energy from fat and carbs while prioritising protein.

While dietary protein will raise your insulin in the short term, prioritising adequate protein allows you to decrease the amount of energy stored on your body. Thus, you can reduce the amount of basal insulin you require to hold your energy reserves in storage over the long term.

But just because increasing your protein % will increase satiety does not mean it’s wise to jump from one extreme (i.e., low-protein to high-protein) to another. Often, this changes the body’s baseline too quickly and usually ends in mental stress, dissatisfaction, and rebound bingeing. If you would like some help dialling in your macros, we’d love you to check out our Macros Masterclass!

Does Protein Spike Your Glucose?

As we’ve mentioned, your pancreas secretes some insulin when you eat a higher-protein meal. Without insulin, you wouldn’t be able to use the amino acids (in protein) to repair muscles and organs, make neurotransmitters, or perform the myriad of other functions you need protein for. Insulin also inhibits the breakdown of your muscles.

Your pancreas also releases glucagon to balance the insulin response to protein, as shown in this chart from Marks’ Basic Medical Biochemistry. This balance between insulin and glucagon is why high-protein % foods cause a minimal rise in glucose.

How Does Protein Impact Blood Glucose?

As part of the Food Insulin Index testing, researchers also determined the Glycemic Index and the Glucose Score. While you might be familiar with the Glycemic Index, the Glucose Score is potentially more useful.

Like the Food Insulin Index, they tested the area under the curve glucose response over three hours. So, foods with a lower Glucose Score will keep your blood sugars more stable after meals.

Again, we have used multivariate regression analysis to understand how macronutrients align with the rise in blood glucose over three hours, showing:

- Protein raises glucose by 9% of that of carbohydrates;

- Fat increases glucose by 6% as much as carbohydrates; and

- The fibre in carbohydrates reduces the glucose impact of carbohydrates by 25%.

The chart below shows protein % vs the rise in glucose over three hours for a range of popular foods. Again, the colouring is based on our satiety index score. You can dive into the interactive Tabluea version of this chart here to find high-satiety foods that will keep your blood glucose stable.

Towards the right, we can see that high-protein, high-satiety foods like egg whites and fish have a minimal impact on glucose.

So, while protein does elicit an insulin response, foods with a higher protein % will help to keep your blood glucose stable and provide greater satiety, help you eat less and thus reduce your basal insulin over time.

Not only will higher-protein % foods help you build precious, metabolically-active lean muscle mass, but you will also feel fuller with fewer calories so you can decrease your body fat levels below your Personal Fat Threshold and thus the total amount your pancreas needs to produce across the whole day.

For more details on the drop or rise you might see in your BG after a high-protein meal, check out Why Does My Blood Sugar Drop (or Rise) After Eating Protein?

Will Protein Turn to Sugar in My Blood?

Protein can be converted to glucose via a process known as gluconeogenesis. However, it is an inefficient process that takes a lot of time and energy. Thus, it tends to happen more readily if you consume minimal carbohydrates. So, your body would prefer to get glucose from carbohydrates and use protein to build your muscles and repair your organs.

Some people with diabetes see a rise in glucose after they eat protein. But, this is not due to the protein instantly turning into chocolate cake in your bloodstream and converting to glucose. Instead, the insulin vs glucagon response becomes imbalanced and excess glycogen is pushed from the liver into the bloodstream due to insulin resistance (in Type-2 Diabetes) or a lack of insulin (in Type-1 Diabetes). As a result, blood glucose rises.

So if you’re managing insulin resistance or Type-2 Diabetes, the solution is not to avoid protein; instead, someone should prioritise it for greater satiety, muscle growth, and fat loss while dialling back carbohydrates and fat. Over time, this will improve body composition.

To manage Type-1 Diabetes, you must consider that protein requires insulin within five hours or so after eating. The insulin requirement for protein is often ignored because the insulin requirement for carbohydrates is much larger. However, insulin dosing for protein becomes more important to manage if you’re on a lower-carb diet, which tends to be higher in protein.

What Is the Best Protein for Me?

As mentioned earlier, bodybuilders will use protein shakes or a quick protein hit to replenish amino acids after a workout. Whey protein shakes are quickly absorbed and highly bioavailable. They also spike insulin to prevent muscle breakdown, which makes them ideal if you want to bulk up.

However, you may not need to resort to protein shakes if you’re not doing heavy workouts. Protein powders are processed and, hence, effectively pre-digested. Thus, they will not provide the same satiety response (or nutrients) as whole-food protein sources.

So, if you’re trying to maximise satiety for weight loss, you should first do what you can to get your protein from whole-food sources and only use powders, shakes, and bars to make up the shortfall.

To help people find nutritious foods that align with their goals and preferences, we have created a wide range of optimised food lists that you can download here.

Summary

- Basal insulin is the insulin your body produces throughout the day to keep your blood glucose stable. Bolus insulin refers to the insulin your body produces at mealtimes.

- Carbs elicit a short-term insulin response, protein a medium-term response, and fat a long-term response.

- Protein tends to keep your blood sugars stable. However, if you have insulin resistance or some form of metabolic dysfunction, your blood sugar may rise after consuming protein.

- Because protein is the most satiating macronutrient, focusing on protein at each meal will allow you to eat fewer calories and remain satiated so you can lose weight and decrease your total insulin production.