In a world where nutritional buzzwords often overshadow the essentials, iodine emerges as a silent guardian of health, metabolism, and overall well-being. Hidden in the depths of the ocean and sprinkled across various foods, iodine is a crucial yet often overlooked mineral that plays a pivotal role in our bodies.

Welcome to the insightful exploration of iodine – the unsung hero among essential nutrients – and where to find it in food. This guide is more than just a list of iodine-rich foods; it’s an enlightening journey through the history, significance, and sources of iodine, interwoven with practical insights on avoiding deficiency.

Whether you’re a health enthusiast, a culinary explorer, or simply curious about this vital mineral, this article is your gateway to understanding and harnessing the power of iodine for optimal health.

Dive in and discover the best food sources of iodine as we unveil the mystery behind this elemental necessity.

History of Iodine

In 1811, Bernard Courtois was extracting sodium salts while manufacturing gunpowder when he noticed a purple vapour emanating from seaweed ash he had just treated with sulphuric acid. Unfortunately, he lacked the funding to keep researching what had just occurred, but he had thought he had just discovered a new element.

Two years later, Charles Desormes and Nicolas Clement made Courtois’s accidental discovery public; he had stumbled upon the element with the atomic number 53, which would be named ‘Iodine’. Its name comes from the word ‘iode’, which means ‘violet-coloured’ in Greek.

In 1873, Casimir Davaine of France discovered that iodine was a powerful antiseptic, even at low concentrations. Today, iodine is still used to sterilise pre-operation sites, wounds, and other injuries. It has been used and continues to be used in the event of nuclear fallouts to protect the thyroid from radioactive damage.

Outside of medicine, iodine has some other pretty cool roles; it’s used to detect counterfeit money and is a component of polarised filters for LCDs, like the one you’re looking at right now. It allows for more compact and efficient propulsion systems when used as a propellant for spacecraft like satellites.

Roles of Iodine in the Body

While iodine is a pretty cool element in technological applications, it’s arguably even more incredible because it keeps you alive! Some of the critical functions of this essential mineral are listed below.

- Your thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland on the front of your neck responsible for producing and storing metabolism-driving hormones like triiodothyronine-3 (T3) and triiodothyronine-4 (T4). Iodine makes up 59% of T3 by weight and 65% of T4. T4 is the storage hormone, and T3 is the more biologically active hormone. Selenoenzymes, or selenium-derived proteins known as iodothyronine deiodinase, convert T4 to T3.

- The thyroid gland traps iodine from the blood, incorporates it into a protein known as thyroglobulin, and turns it into thyroid hormones that are stored and released in circulation as needed. 70-80% of the body’s iodine stores are thus stored in the thyroid as thyroid hormones.

- Thyroid hormones regulate many physiological and metabolic processes, like metabolic rate, reproduction, growth, and development.

- Besides the thyroid, iodine is found in concentrated amounts in the salivary glands, gastric mucosa, lactating mammary glands, eyes, thymus, skin, placenta, ovaries, uterus, prostate, and pancreas. Hence, it’s likely critical for many actions outside the thyroid.

- Recently, iodine was shown to be a component in iodolipids, organic fatty acids containing iodine. These compounds are known to play a role in thyroid autoregulation and thyroid cell proliferation.

- Iodine is a member of the halogen family, which also includes Bromine, Fluorine, and Chlorine. It is the heaviest of the four, meaning adequate iodine intake is known to ‘bump out’ and protect against these toxic, harmful substances.

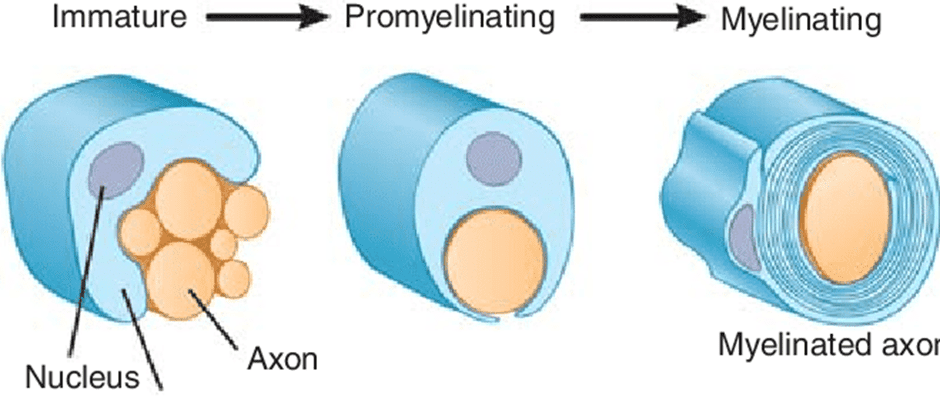

In foetal development, iodine is critical for forming the brain’s cortex and nerve connections. Additionally, it’s essential for myelination, the process that results in the fatty covering and protection of nerves.

- The body requires iodine-rich foods for innate immunity. Leukocytes—or white blood cells—use iodine in cell-induced immunity to fight bacterial and viral infections.

- Iodine functions as an antioxidant in many parts of the body, protecting it from peroxides and radicals. Where iodine deficiency is present, DNA damage to the thyroid gland has resulted in lab animals. Thyroid nodules were found in human subjects.

- Additionally, iodine has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects and lower iodine levels have been associated with higher instances of inflammation and inflammatory diseases.

- Studies have shown that iodine has been positively associated with ocular health, and higher levels have been associated with improved visual acuity, macular degeneration, myopia, and colour perception.

- Iodine has been shown to regulate estrogen metabolism and have an anti-estrogenic effect in animal models.

- Iodine is critical for cellular regeneration, making it essential for healthy skin, nails, and hair. Additionally, it is necessary for maintaining the skin’s moisture levels.

- Because of its role in thyroid health, iodine is essential for cardiovascular health, as hypothyroid-like conditions result in irregular lipid metabolism, decreased myocardial contractility, and increased peripheral vascular resistance.

- Iodine has been shown to help antagonise various heavy metals like lead and protect the body from the oxidative damage they create.

- Iodine has been shown to protect against pancreatic alterations related to hypothyroidism in human rabbits.

Best Food Sources of Iodine

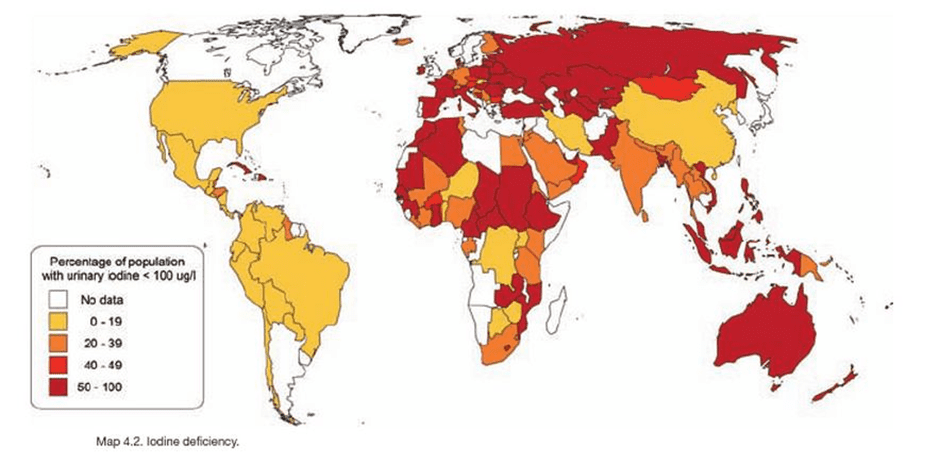

Iodine is found in concentrated sources in and around oceans; it originates in the sea and works its way into the soil. Hence, aquatic beings like fish, shellfish, and seaweeds are the best sources, and mountainous and landlocked regions are the most deficient. Lands once covered by oceans may have some iodine, but this nutrient is rapidly depleted by erosion.

Listed below are some of iodine-rich foods.

Animal Foods

- grass-fed beef

- eggs

- milk

- cheese

- yogurt

- kefir

- butter

Seafood

- sardines

- anchovies

- tuna

- seabass

- shrimp

- lobster

- clams

- cod

- oysters

- mussels

- seaweeds (i.e., kombu, wakame, kelp, etc.)

Plant Foods

- potatoes (with skin)

- mushrooms

- prunes

- lima beans

- green peas

- cantaloupe

- watermelon

- strawberries

- tomatoes

Processed foods contain virtually no iodine. So, if you’re not consuming iodine-rich foods from the sea or other nutrient-dense whole foods—or even if they are, but those nutrient-dense whole foods aren’t grown or raised in iodine-rich soils—hitting your iodine goal can be challenging.

Iodine is one nutrient that largely depends on soil content. This is why iodised salt is almost the only source of iodine for someone consuming a standard Western diet.

Iodine Antagonists and Synergists

Essential vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, and amino acids work antagonistically and synergistically. In synergism, one nutrient can compound the effects of another nutrient and increase retention. In antagonism, one nutrient can decrease the functions of another and deplete your reserves of it.

Because of its role in thyroid function, iodine works synergistically with selenium, iron, vitamins A, C, D, and B vitamins, magnesium, zinc, copper, and tyrosine. Consuming more of this nutrient complex tends to increase and ‘reinforce’ the functions of iodine.

In contrast, minerals like fluorine, chlorine, and bromine tend to antagonise iodine; while these nutrients aren’t essential, they’re widespread in our environment. Additionally, certain antinutrients known as goitrogens can antagonise the absorption of iodine, decreasing levels over time.

High-goitrogen foods include cruciferous vegetables, cassava, soy, beans, sweet potatoes, collards, kale, mustard greens, rapeseed, rutabagas, and turnips. However, goitrogens are easily destroyed by high-heat cooking methods. Usually, these foods are problematic for someone who relies on them as staples or someone with a pre-existing thyroid condition.

You only need to worry about nutrient synergism and antagonism if you are not consuming iodine-rich foods and supplementing with nutrient isolates or you are eating a LOT of one food that’s very high in a few vitamins, minerals, amino acids, or fatty acids. On the other hand, if you consume a nutrient-dense, varied diet, these properties tend to look after themselves.

Factors Increasing Demand

You will need more iodine if you have breast cancer, diarrhoea, excessive carbohydrate intake, obesity, are pregnant, have a goitre or consume a lot of goitrogen-rich foods (like cabbage, turnips, Brussels sprouts and cassava).

Recommended Daily Intake of Iodine

The thyroid gland needs no more than 70 micrograms per day of iodine to synthesise T4 and T3. However, this only makes up a portion of what we require iodine for; it is also necessary for the many roles we explained above and to nourish an infant via breastmilk.

Nonetheless, the US Recommended Daily Intake for iodine is 150 micrograms in adults over 19. However, this need nearly doubles during pregnancy and lactation, with the RDI climbing to 220 micrograms and 290 micrograms, respectively.

Unfortunately, because iodine in food is so variable depending on where it’s grown, it is often not tracked in food databases.

Iodine Deficiency

Even 5600 years ago, the harms of iodine inadequacy were well known; Chinese medical writings from this time document goitres decreasing in size after consuming seaweed and burnt sea sponge!

It’s estimated that 2 billion globally are deficient worldwide, with 45% of the European population not getting enough. To complicate things further, it’s estimated that a pregnant or breastfeeding woman’s needs increase by almost 50%.

As you learned earlier, iodine is critical for synthesising thyroid hormones. Hence, deficiency can lead to hypothyroidism or an under-functioning thyroid resulting from the body’s inability to produce thyroid hormones. As a result, someone may experience

- goitre (see image below),

- reduced metabolic rate,

- depression,

- low basal body temperature,

- weight gain,

- cognitive dysfunction,

- brain fog,

- hormonal imbalance,

- fatigue, and

- death.

Severe physical and mental retardation, known as cretinism, can also result from deficiency, especially if iodine is deficient during development. Because iodine is critical for nervous system development, iodine deficiency in pregnant mothers, babies, and infants is the most widespread but preventable cause of brain damage. Iodine deficiency in pregnancy can also result in mental retardation as well as miscarriage, preterm birth, and neurological impairments.

Iodine deficiency is usually diagnosed by testing the urine. We pee out 90% of the iodine we consume within 24-48 hours of consumption. Thus, administering a higher dose and measuring excretion can indicate whether or not deficiency is present; someone that retains a lot of it needs more, and vice versa.

Tolerable Upper Limit and Toxicity

The Tolerable Upper Limit (UL) has been set at 1,100 mcg per day (1.1 mg).

However, this is largely disputed, as the Japanese—one of the healthiest populations worldwide—are known to consume 5,280 to 13,800 micrograms (5.28 to 13.8 milligrams) per day from seafood and seaweeds. Many regard the Japanese as one of the healthiest populations in the world; their incidence of thyroid disease is only 07.-2.1%, so what gives?

Many studies on iodine toxicity point out that the condition often results from supplementation, not food. Additionally, the form of iodine tends to matter; radioactive iodine, those used in contrast dyes, and certain supplement forms are unnatural, and the body does not manage them well. Conditions like thyrotoxicosis also tend to result if someone loses the ability to handle excess iodine, like when they’ve been deficient for a while.

Iodine toxicity has been shown to present itself as:

- iodine-induced hyperthyroidism;

- thyroiditis;

- hypothyroidism;

- cancer (radioactive forms);

- GI upset;

- nausea;

- vomiting;

- diarrhea;

- rash;

- delirium;

- stupor; and

- shock.

If you are using an iodine isolate, it’s essential to supplement under a knowledgeable individual’s care. If you have thyroid antibodies—or autoimmune thyroid disorders run in the family—too much iodine, especially in the form of potassium iodide, can trigger or exacerbate autoimmune thyroid disease. Additionally, if you have an ‘iodine allergy’, it’s best to be cautious when using iodine supplements or high-iodine foods.

Fortification and Iodization

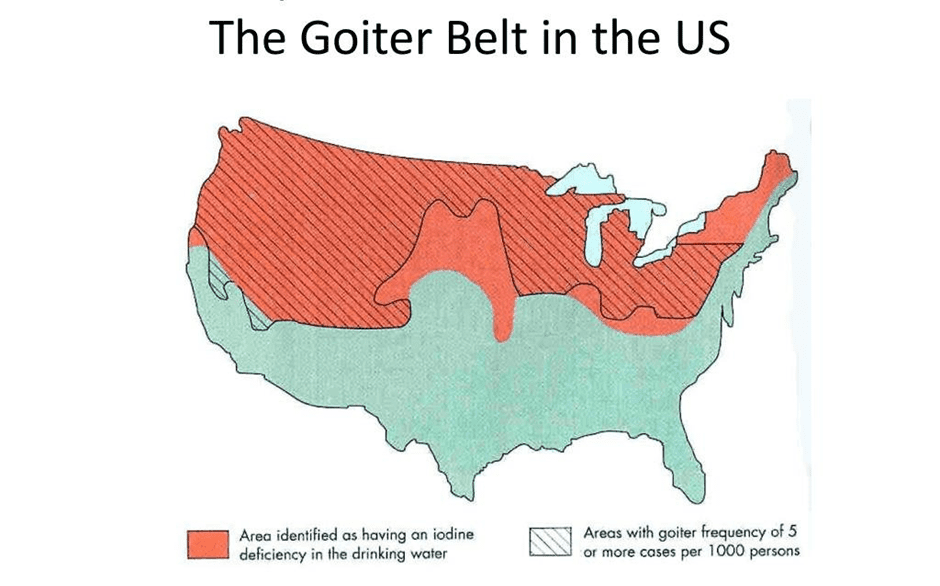

In the 1910s and 1920s, there was an epidemic of iodine-deficient-related thyroid disorders throughout the United States. Soils of most flooded river valleys, inland regions, and mountainous regions like the Appalachians, Alps, Atlas, Andes, and the Himalayas are often deficient in iodine. Hence, the US ‘goitre belt’ was hit by relentless iodine deficiency during this time.

In 1922, Dr David Cowie of the University of Michigan (pictured below) proposed fortifying table salt to prevent goitre. This led to the release of the first iodised salt product in 1924. Many countries that also struggled with low iodine intakes followed suit, with India making it available in the 1950s and China in the 1960s. Around 120 countries now have formal fortification programs.

To date, 80 to 90% of households have access to iodised table salt worldwide. Since the fortification of salt began in the US, a 2013 study showed that the IQ of iodine-deficient regions increased by nearly 15 points since introducing iodised salt and 3.5 points nationally.

Iodine has a heavy atomic mass, meaning its abundance tends to decline with time. Additionally, humid and high-temperature climates can accelerate the decay of iodide, the form found in table salt.

Iodine in Food vs. Iodine in Supplements

There are many different conditions related to ‘iodine toxicity’. So, why can some populations consume high amounts, but others cannot?

Iodine is one of the many nutrients for which cofactors matter, as its metabolism depends on other nutrients, like selenium. In one study looking at the effects of selenium on iodine toxicity, it was shown to alleviate the symptoms of iodine excess.

The takeaway from this finding is that it’s best to get your iodine—and any other nutrient, for that matter—from food and to avoid taking supplements as much as possible!

Food provides the complete spectrum of iodine cofactors like vitamins A, C, D, and B vitamins, magnesium, selenium, zinc, copper, tyrosine, and other nutrients that support iodine metabolism. As a result, it’s much harder to overdose on iodine from food! It’s also much easier to get the complete complex of nutrients your body requires to function optimally.

Nutrient Series

Minerals

- Calcium

- Iron

- Magnesium

- Phosphorus

- Potassium

- Sodium

- Zinc

- Selenium

- Copper

- Manganese

- Chromium

- Molybdenum

- Biotin (B7)

- Iodine

Vitamins

- Vitamin A

- Vitamin E

- Thiamine (B1)

- Riboflavin (B2)

- Niacin (B3)

- Pantothenic acid (B5)

- Vitamin B6

- Folate (B9)

- Vitamin B12

- Vitamin C

- Vitamin D

- Choline

- Vitamin K1

- Vitamin K2