Chromium, a critical micromineral, plays a substantial role in our bodies, particularly in optimizing insulin sensitivity.

Though it’s required only in trace amounts, its impact is profound. However, the data regarding chromium content in various foods is not extensively recorded, leaving many unaware of how to obtain it through their diet.

This article sheds light on the vital functions of chromium, highlights symptoms associated with its deficiency, and provides a thorough list of food sources rich in chromium.

Embark on this informative journey to understand how chromium acts within your body and how you can ensure its adequate intake through a balanced diet.

History of Chromium

In 1797, the mineral chromium by the French chemist Louis Nicholas Vauquelin as a naturally occurring, brilliantly coloured element. Hence, chromium got its name from the Greek word for colour, ‘chroma’. You can find it as number 24 on the periodic table.

In 1957, Schwarz and Mertz noticed there was a ‘glucose tolerance factor’ (GTF) absent in the feed of rats they were studying. In 1959, they determined this compound was chromium and that this mineral had physiological action within the human body.

In the 1970s, chromium was recognised as an essential trace mineral in humans when a patient receiving total parenteral nutrition (TPN) developed symptoms of diabetes when this nutrient was absent from their feeding tube.

Exogenous (injected) insulin made no dent in their symptoms, but supplemental chromium did; nowadays, chromium is regularly added to TPN solutions and is recognised for its important role in glucose metabolism.

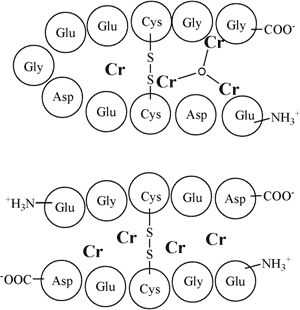

Chromium is often found in its trivalent (Cr3+) form. This allows it to form complexes with proteins and nucleic acids, making it easy for the human body to incorporate. It is not to be mistaken for the hexavalent chromium (Cr6+) that was the troubling compound in the movie Erin Brockovich that was poisoning the California groundwater systems thanks to local municipalities.

Hexavalent chromium (left) and trivalent chromium (right).

To date, no Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) has been set for chromium (note: the EAR is the average daily intake of a nutrient that appears to be sufficient for 50% of healthy individuals).

Thus, the Adequate Intake (AI), or the amount of a nutrient that is assumed to be adequate when there isn’t enough evidence to develop an EAR, was used to set our Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA). Unfortunately, this means the research on chromium is sparse!

Within the human body, we hold around five to six milligrams (mg) of chromium in our tissues. Although we only lose about one microgram of chromium daily via urinary excretion, our recommended intake for chromium has been set at anywhere from 30 to 200 mcg, with 50 mcg being the go-to recommendation. Americans ingest about half of that, with women consuming 25 mcg and men consuming 33 mcg, on average.

The table below shows the Adequate Intakes for Chromium.

| Age | Male | Female | Pregnancy | Lactation |

| Birth to 6 months* | 0.2 mcg | 0.2 mcg | ||

| 7–12 months* | 5.5 mcg | 5.5 mcg | ||

| 1–3 years | 11 mcg | 11 mcg | ||

| 4–8 years | 15 mcg | 15 mcg | ||

| 9–13 years | 25 mcg | 21 mcg | ||

| 14–18 years | 35 mcg | 24 mcg | 29 mcg | 44 mcg |

| 19–50 years | 35 mcg | 25 mcg | 30 mcg | 45 mcg |

| 51+ years | 30 mcg | 20 mcg |

Some of the highest chromium concentrations in the human body include the spleen, testes, epididymis, and bone marrow, which could highlight some organs and organ systems that require more chromium. Additionally, this can give us some indication of which animal foods contain more chromium.

What Does Chromium Do for the Body?

We should clarify and highlight that we are still learning about chromium’s roles and interactions within the human body. However, most of the benefits of chromium relate to glucose and insulin metabolism.

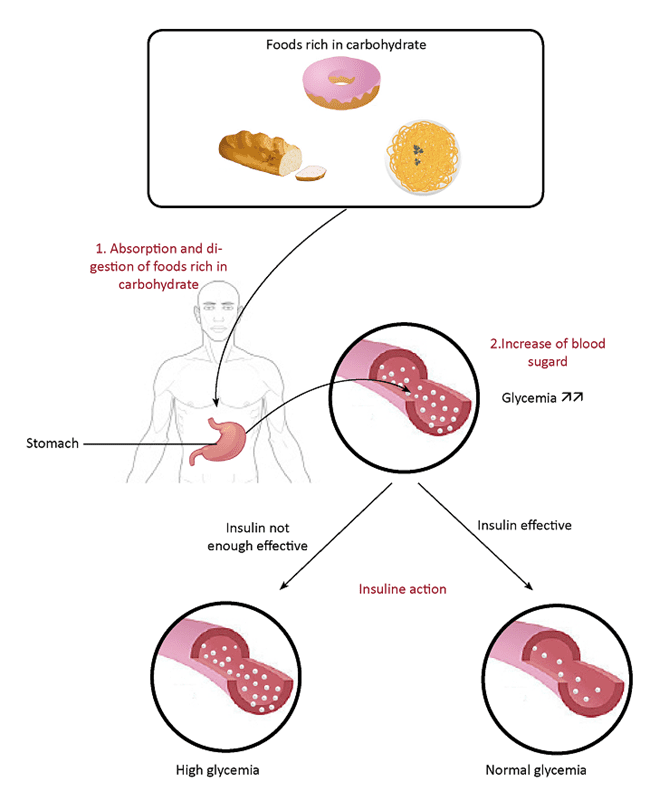

Chromium is a cofactor of the oligopeptide chromodulin—otherwise known as low-molecular-weight chromium-binding substance (LMWCr)—that facilitates the release of insulin. Ultimately, chromium is most well-known for its ability to increase insulin sensitivity and improve glucose transport into cells; it does so by inhibiting the enzyme that cleaves phosphate from the insulin receptor. Clinically, it is used as an adjunct in high amounts for people with diabetes.

- In addition to its role in insulin sensitivity, chromium has been shown to amplify the effects of insulin by binding to insulin-activated insulin receptors and increasing the actions of insulin. No other ions have been shown to have a similar effect.

- In a recent mouse study, subjects with diabetes were administered chromium. Researchers noted that chromium might help inhibit insulin breakdown, which could help facilitate glucose clearance. This was linked to a reduction in oxidative stress and inflammation that often results from high glucose, which can feed into the cycle of insulin resistance.

- Studies have shown that higher serum chromium levels are linked to lower serum cholesterol levels and low-density lipoprotein (LDL).

- Because of its role in insulin release, chromium has been linked to increased muscle mass. This is because insulin is essential for utilising amino acids in dietary protein.

- Low serum chromium levels are associated with symptoms resembling diabetes mellitus.

What Are the Symptoms of Chromium Deficiency?

To date, no clinically defined state of chromium deficiency exists. However, several symptoms and conditions are associated with low serum chromium levels based on animal models and humans on long-term TPN. Most of the conditions stem from poor glucose regulation. These include:

- Diabetes-like symptoms, like reduced insulin sensitivity and glucose regulation;

- Impaired glucose and lipid metabolism;

- Increased cardiovascular risk;

- Peripheral neuropathy;

- Atherosclerosis;

- High cholesterol or triglycerides;

- Weight gain or weight loss;

- Impaired coordination and

- Confusion.

When Would I Need More Chromium?

Studies have indicated that people who eat a high-glycemic diet or have high insulin levels may need more chromium because of its role in insulin metabolism. Research also showed that these people may have altered excretion and absorption levels, which may indicate increased demand.

Aside from people with blood sugar regulation problems, people who are older, more physically active, more stressed, recovering from infections or myocardial infarction, or who have reduced digestive capabilities might require more chromium.

Does Chromium Help with Weight Loss?

Like almost every other essential vitamin, mineral, fatty acid, and amino acid, eating or taking more chromium does not necessarily mean you will instantly shed pounds. However, chromium is involved in a list of metabolic processes influencing healthy body weight.

Higher serum chromium levels have been shown to increase insulin sensitivity, which regulates blood glucose and insulin, which can normalise and improve cravings and satiety.

Additionally, its insulin-regulatory properties play a role in muscle protein synthesis, which helps us build lean muscle mass. More muscle mass stokes our metabolism and raises our metabolic rate.

Synergistic Nutrients with Chromium

While we won’t go into detail about every synergistic relationship, it is essential to note that most of the nutrients included below are involved in glucose transport and utilisation. Hence, they work with chromium to keep your blood sugars stable and regular.

These nutrients include, but are not limited to:

- Vitamin A,

- Thiamine (B1),

- Riboflavin (B2),

- Niacin (B3),

- Pyridoxine (B6),

- Vitamin C,

- Vitamin E,

- Magnesium,

- Iron,

- Zinc,

- Manganese,

- Potassium, and

- Phosphorus.

Aside from glucose transport and utilisation, nutrients like vitamin C have been shown to increase chromium uptake in animal studies when administered simultaneously.

It’s important to remember that almost all essential vitamins and minerals have some sort of synergistic relationship because many interact somewhere down the line in human metabolism.

While they may not be direct relationships, it’s essential to focus on consuming a complete array of nutrients to ensure your body has an even amount of resources and not just a lot of one. Remember: it’s about the ‘sum of the parts’!

Antagonistic Nutrients of Chromium

Antagonists refer to nutrients that directly decrease chromium absorption and increase our demands for it. You can think of them as the movie antagonists or the bad guys that usually go against the main character.

The following nutrients and compounds are known as either direct or indirect chromium synergists:

- Vitamin B10 (PABA),

- Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin),

- Vitamin D,

- Copper,

- Iron,

- Carbohydrates,

- Estrogen, and

- Lead.

We have included a bit more detail on some of these interactions below where the information was available.

Vitamin D increases the absorption of calcium. Additionally, vitamin D can increase insulin synthesis, meaning vitamin D and calcium can raise our Cr demand and deplete it over time.

Research and hair-tissue mineral analysis (HTMA) have shown that the calcium:magnesium ratio is critical for balanced chromium levels. Maintaining a Ca:Mg ratio of around 7.1:1 for optimal chromium uptake and utilisation.

For more on nutrient ratios, check out Nutrient Balance Ratios: Do They Matter, and How Can I Manage Them?

Copper is considered an indirect chromium antagonist because it increases serum estrogen, calcium, and vitamin D levels, which are all known to deplete chromium.

Lead (Pb) is a toxic element that impairs many biochemical processes when it accumulates in the body. Because of its atomic weight, it is known to ‘mimic’ and fit itself into the place of essential minerals with similar charges, which cannot be used in the same way. You can think of it as shoving a safety into an electric plug.

Although iron and chromium compete for binding sites of the iron transport molecule transferrin, high supplementation with chromium was not shown to decrease or negatively influence iron levels. However, conditions related to iron overload and excess iron (i.e., haemochromatosis) may interfere with chromium uptake and utilisation. This is interesting, as high iron levels and diabetes mellitus are known to coexist.

Carbohydrates demand the release of insulin. Hence, a diet rich in sugary carbohydrates increased the excretion of chromium in subjects.

Chromium and Satiety

Because there is limited data on the amount of chromium in varying foods, we do not have much information on the relationship between satiety and chromium as we do for the other more well-known nutrients. However, that can change in time!

Although our data is limited, many studies show chromium is critical for healthy glucose and insulin responses. Hence, consuming more chromium-rich foods should—theoretically—give your body the raw ingredients to regulate insulin and manage glucose more efficiently. Additionally, we could add that increasing your intake of nutrient-dense whole foods that provide you with more protein, fibre, and other satiating micronutrients will also provide you with more chromium.

Lastly, it’s essential to remember that a chromium supplement likely does not have the same satiety influence as whole foods containing more chromium. While it may be more helpful in a clinical setting for a targeted purpose, foods containing more chromium tend to include other micronutrients that also influence satiety.

For our complete satiety analysis, check out The Cheat Codes for Optimal Satiety and Health.

What Foods Are High in Chromium?

As we mentioned in the introduction, data on chromium in foods is not as readily available as it is for other nutrients. Additionally, the amount of chromium varies by as much as 50-fold in samples of the same foods grown in different places! Hence, the chromium contents of foods highly depend on the soils they are grown in.

Plant

- Brewer’s Yeast,

- Broccoli,

- Green beans,

- Potatoes,

- Apple with peel,

- Banana,

- Lettuce,

- Grape juice, and

- Tomatoes.

Animal-Based

- Mussels,

- Rabbit liver,

- Pork kidney,

- Beef liver,

- Colostrum,

- Haddock,

- Chicken breast, and

- Ham.

Chromium is most often added to multivitamins and sold as an isolate as chromium picolinate.

Nutrient Series

Minerals

- Calcium

- Iron

- Magnesium

- Phosphorus

- Potassium

- Sodium

- Zinc

- Selenium

- Copper

- Manganese

- Chromium

- Molybdenum

- Biotin (B7)

- Iodine

Vitamins

- Vitamin A

- Vitamin E

- Thiamine (B1)

- Riboflavin (B2)

- Niacin (B3)

- Pantothenic acid (B5)

- Vitamin B6

- Folate (B9)

- Vitamin B12

- Vitamin C

- Vitamin D

- Choline

- Vitamin K1

- Vitamin K2