Fasting glucose is a critical marker of your overall metabolic health, not just a commonly used method to diagnose pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes.

Many people in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenge ask how they can control their fasting glucose. While there are some short-term ‘hacks,’ lowering your waking glucose is mostly a long-term game.

This article, based on the analysis of 854,632 glucose values from 8,880 people who have used the Data-Driven Fasting app, will give you insights that will empower you to take control of your weight, body fat and metabolic health.

What is Fasting Glucose?

Fasting glucose, or waking glucose, is your glucose value when you wake after sleeping all night (an overnight ‘fast’) before you eat anything. Fasting glucose is a common test ordered by your doctor, but it can also be checked at home.

In our programs, we suggest people test their waking glucose with a glucometer as part of their normal morning routine, after getting out of bed but before coffee and food.

What is a Normal Fasting Glucose Level?

The table below shows the blood glucose values used to diagnose pre-diabetes and Type 2 diabetes.

- A fasting glucose below 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) is considered “normal”.

- Type 2 diabetes is diagnosed after two fasting glucose readings above 126 mg/dL (7.0 mg/dL).

- Pre-diabetes is the zone between normal and type 2 diabetes.

| Fasting | After-Meal | HbA1c | |||

| mg/dL | mmol/L | mg/dL | mmol/L | % | |

| ‘Normal’ | < 100 | < 5.6 | < 140 | < 7.8 | < 5.7% |

| Pre-Diabetic | 100 – 126 | 5.6 to 7.0 | 140 to 200 | 7.8 to 11.1 | 5.7 to 6.4% |

| Type 2 Diabetic | > 126 | > 7.0 | > 200 | > 11.1 | > 6.4% |

Doctors often use these cut-offs to prescribe diabetes medications like metformin or insulin. However, rather than simply addressing the symptoms, it’s ideal to address the root cause well before you require medication.

How to Hack Your Fasting Glucose (Short Term)

Over the three years of running Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, we have identified a few ‘hacks’ that often lead to lower waking glucose levels.

Stop Eating Earlier

If your last meal is late in the day, it makes sense you will have more energy stored in your system the next morning when you wake, so your fasting glucose will be higher. We also tend to make poor food choices after dinner and late at night, which overfills our energy stores.

Incrementally moving your last bite of food a little earlier (i.e., 9 pm rather than 10 pm) will help lower your glucose when you wake.

Smaller Dinner

Eating less at dinner also leads to lower waking glucose the next day. It helps you be hungrier for a robust meal earlier in the day, making you less likely to binge at night.

Eating most of your food late at night means your body will be working harder to digest, metabolise, and store the energy from dinner. If your schedule allows it, eating most of your food during the day when the sun is out and your body needs more energy is ideal.

Prioritise Protein

If your glucose is higher in the morning due to the dawn phenomenon, prioritising protein (with less energy from fat and carbs) at your first meal when you first feel hungry helps your blood sugars fall again quickly and leads to stable blood glucose across the day and less likely to overeat at night.

Less Fat and More Carbs at Dinner

Counterintuitively, having more carbohydrates and less fat at dinner often leads to lower waking glucose. A large high-fat meal at night can overfill your fat fuel tanks, which means the glucose ends up backing up in your system when you wake. Conversely, a lower-fat meal with some carbohydrates increases insulin, lowering overnight gluconeogenesis and lowering glucose the next morning.

What is the Typical Range of Fasting Glucose?

The charts below show the distribution of fasting glucose values logged in the DDF App. The first chart shows glucose in mg/dL (used in the US), while the second chart shows mmol/L (used by the rest of the world).

Notice, towards the right, that some people exceed the cut-off for type 2 diabetes while many exceed the cut-off for pre-diabetes.

Because your liver always works to ensure enough glucose in your bloodstream, very few people see a fasting glucose below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).

What is the Optimal Target for Fasting Glucose?

Below are several charts showing factors that align with elevated fasting glucose. This deeper understanding will help you improve your metabolic health and address the root cause of elevated fasting glucose and insulin levels — energy toxicity.

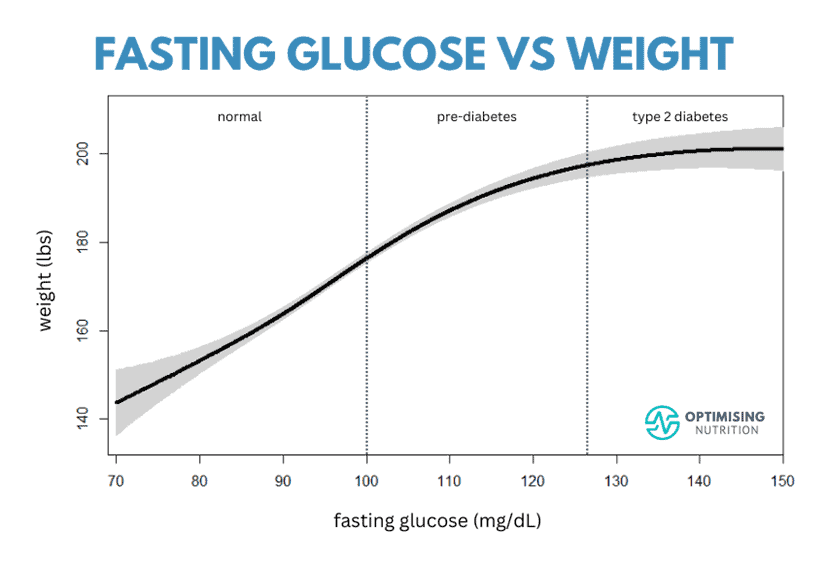

Fasting Glucose vs Weight

This first chart shows the root cause of elevated fasting glucose — people with higher weights have higher fasting glucose.

Notice that people in the type 2 diabetes zone aren’t necessarily a lot heavier. Counterintuitively, insulin-sensitive people can gain more weight more easily than those who are insulin-resistant.

Fasting Glucose vs Body Mass Index

Similarly, people with a higher body mass index (BMI) also have higher fasting glucose.

- A BMI of 30 (i.e., the cut-off between overweight and obese) corresponds to a fasting glucose of around 108 mg/dL (6.0 mmol/L).

- Meanwhile, the normal BMI of 25 corresponds with a much lower fasting glucose.

A lower BMI tends to align with a low hazard ratio (i.e. risk of dying of any cause).

However, being underweight (i.e. anorexia or sarcopenia) is not ideal due to an increased risk of infections and frailty. See Optimal BMI for Longevity and Optimal Health (And How to Achieve It) for more details on navigating a healthy BMI.

Fasting Glucose vs Body Fat

BMI is popular because it’s easy to measure. All you need is your weight and height.

But it’s even more important to keep an eye on the balance between lean mass and fat in your body. It should be no surprise that a higher fasting glucose corresponds with a higher body fat %.

Note: Men tend to have a lower body fat % than females. However, the chart above shows all our data combined, which is around 80% female, with a high proportion of postmenopausal women.

Professor Roy Taylor’s recent research has given us some powerful insights into the root cause of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome.

While it’s easy to think that diabetes is a form of ‘carbohydrate intolerance’, metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance occur when our body fat stores become full and can no longer accept more energy from the low-satiety, nutrient-poor food that we continue to eat.

Fasting Glucose vs Waist

The chart below shows that people with a larger waist circumference tend to have higher fasting glucose.

People reach their personal fat threshold at different body fat levels depending on their genetics and other factors. You can be large and metabolically healthy (i.e. metabolically healthy obesity).

It’s when your fat fuel tank can no longer accept more energy that being overweight becomes dangerous. Excess fat gets stored in your liver and other vital organs, so you see a higher waist circumference.

A higher fasting glucose is an early indication that you are reaching your personal fat threshold and need to take action to reverse the progression.

Fasting Glucose vs Waist-to-Height Ratio

People with a larger waist-to-height ratio have a higher fasting glucose.

- The cut-off between healthy and overweight (W:H = 0.53) aligns with a fasting glucose of 92 mg/dL (5.1 mg/dL).

- The cut-off between overweight and obese (W:H = 0.58) aligns with a fasting glucose of 108 mg/dL (6.0 mmol/L).

- The cut-off between obese and highly obese (W:H = 0.63) aligns with a fasting glucose of 129 mg/dL (7.2 mmol/L).

The chart below, from Waist-to-Height Ratio Is More Predictive of Years of Life Lost than Body Mass Index, shows that a waist-to-height ratio of 0.5 aligns with the lowest risk.

Fasting Glucose vs Systolic Blood Pressure

Fasting glucose also aligns with a higher systolic blood pressure. Conversely, people with normal fasting glucose in the normal range also tend to have healthy blood pressure.

While high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes and many other related diseases are diagnosed separately, with different drugs to treat them, they tend to be clustered together because they are due to the same root cause (i.e. energy toxicity).

Fasting Glucose vs Post Meal Glucose

Many people like to focus on their glucose after they eat or maintain stable blood glucose, but people with high fasting glucose will also see higher glucose after they eat.

Changing what you eat can help lower your glucose after you eat, but the best way to lower your post-meal glucose is to focus on the things that lower your fasting glucose and move the needle on your overall metabolic health.

Fasting Glucose vs Rise in Glucose After Eating

It’s fascinating that people with high fasting glucose tend to see a larger rise in their glucose after they eat. Once your body fat stores are full, the excess energy from your food backs up into your bloodstream, and you will see higher glucose values after eating.

Larger rises in glucose often lead to rapid falls in glucose, which can lead us to want to eat sooner and make poorer food choices. This is known as reactive hypoglycaemia.

Some fluctuation in glucose after you eat is a normal, healthy part of appetite signalling. Simply swapping the carbohydrates in your diet for fat won’t improve your overall metabolic health unless it also reduces your body fat, waist, weight and fasting glucose.

Fasting Glucose vs Premeal Glucose

Our data shows that your glucose before eating is the biggest predictor of fasting glucose.

- To move from type 2 diabetes to pre-diabetes, you need to get your premeal glucose under 110 mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L).

- To move from pre-diabetes to normal glucose control, you need to get your premeal glucose below 94 mg/dL (5.2 mmol/L).

How to Lower Your Fasting Glucose

In our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges, the DDF App guides Optimisers to wait until their glucose is below normal before they can eat. This process of draining the excess glucose allows their bodies to get on with using the stored fat.

The chart below from Muffy, one of our original Optimisers, shows how this process impacted her waking (or fasting) glucose over the long term.

Beyond the numbers, this is what it looks like on the outside!

You can read more about Muffy’s amazing transformation using Data Driven Fasting here.

Fasting Glucose on a Lower Carbohydrate Diet

Most people on a lower carbohydrate diet tend to see higher glucose levels earlier in the day but lower glucose later in the day. Overnight, their liver ensures they have plenty of glucose in their system, ready to start the day.

As they progress through the day, their bodies use up the glucose in their blood and see their premeal glucose slowly fall, as shown in the example hourly chart from the DDF app below.

People on a lower fat, higher carbohydrate diet tend to see the reverse. They wake with lower fasting glucose and fill their glucose fuel tank throughout the day with food.

So, if you see slightly higher than optimal fasting glucose on a lower-carb diet, there’s no need to be too concerned so long as your other markers, like waist-to-height ratio, body fat and premeal glucose, are dialled in.

Conclusion

Our comprehensive analysis of fasting glucose underscores its vital role in assessing and managing metabolic health.

By understanding the normal ranges and factors that affect those ranges and taking steps to attain and maintain healthy fasting glucose levels, individuals can prevent or reduce the progression of pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes.

The insights gathered from the Data-Driven Fasting app highlight the importance of personalized approaches to health and empower you to take control of your well-being through informed data-driven decisions.

More

- Data-Driven Fasting: Use Your Blood Glucose as a Fuel Gauge to Lose Weight and Optimise Your Metabolic Health

- Mastering Blood Sugar: Insights for Non-Diabetics

- Blood Glucose and Hunger: Decoding the Intimate Relationship

- Ideal Blood Sugar Levels for Weight Loss: How to Achieve and Maintain Them

- Data-Driven Fasting Challenge