Indulging in the latest diet fads might seem like a modern phenomenon, but the real story of nutritional trends spans much longer and is deeply intertwined with historical events and technological shifts.

This exploration dives into the long-term trends that have defined our nutritional journey over the last century. From the impact of world wars to the advent of synthetic fertilisers, discover how our food choices have evolved and what these shifts mean for our health and society at large.

Unveil how understanding our nutritional past can empower us to navigate the diabolical health challenges looming and take a step towards a better nutritional future.

What Are the Current Trends in Nutrition?

Scientifically speaking, and for the sake of this article, trends are a general direction in which something is developing or changing.

Rather than dietary fads, we’ll be examining long-term trends that are influenced by:

- world wars and depressions,

- politics and government subsidies,

- paradigm shifts in food processing,

- the creation of synthetic fertilisers made from fossil fuels and

- the introduction of artificial flavourings, colourings, and sweeteners that compensate for the lack of flavour associated with the lack of nutrients in processed foods.

As you will see, the long-term data shows that our intake of micronutrients and macronutrients has shifted substantially, not for the better. We can attribute these changes to farming techniques that maximise production, government subsidies, innovation in flavour technologies, and the widespread use of artificial sweeteners that makes processed foods hyperpalatable.

Humans have created innovative technologies to get more food with less effort for as long as we have been around. Around ten thousand years ago, we domesticated grains, which created greater food security and allowed us to settle down and build cities rather than move around in search of new food.

Over the past fifty years, we have made massive technological breakthroughs that have changed our food forever. With the industrialisation of agriculture, food has become more plentiful and tastier. However, as we will see, our food now contains fewer essential micronutrients, or the essential vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and essential fatty acids we require to thrive and truly satisfy us.

The Data

For this analysis, the macro and micronutrient data we’ve used is taken from the USDA Economic Research Service. The obesity data is from the United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

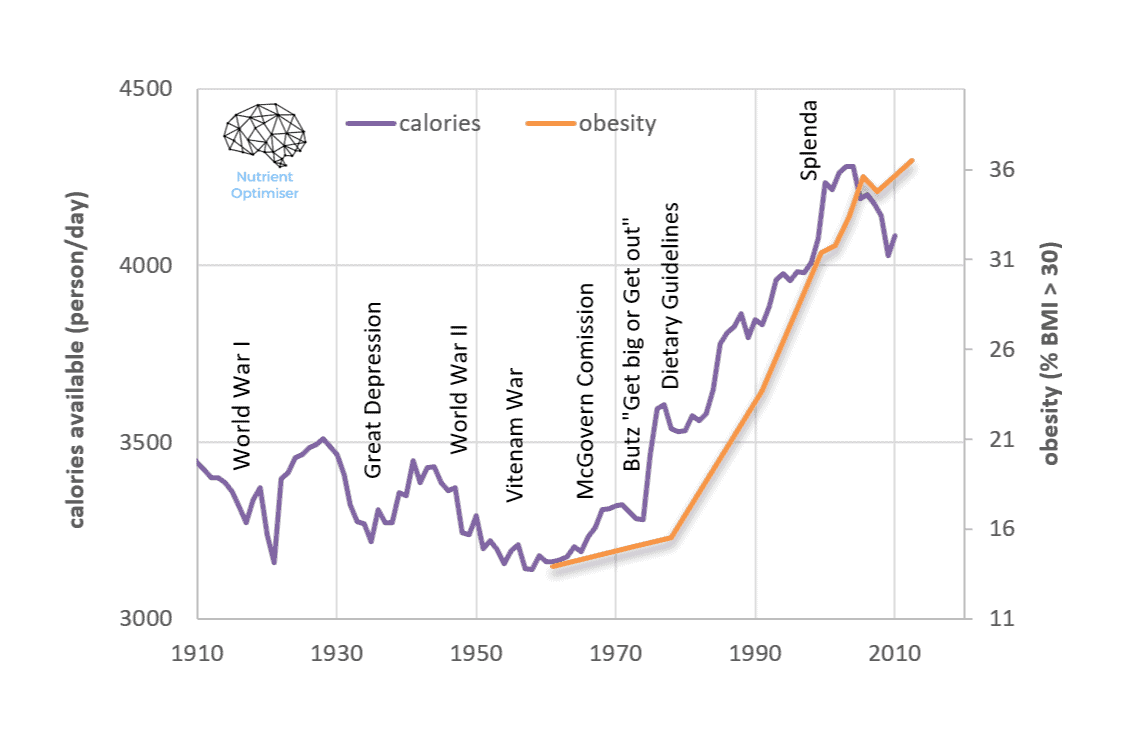

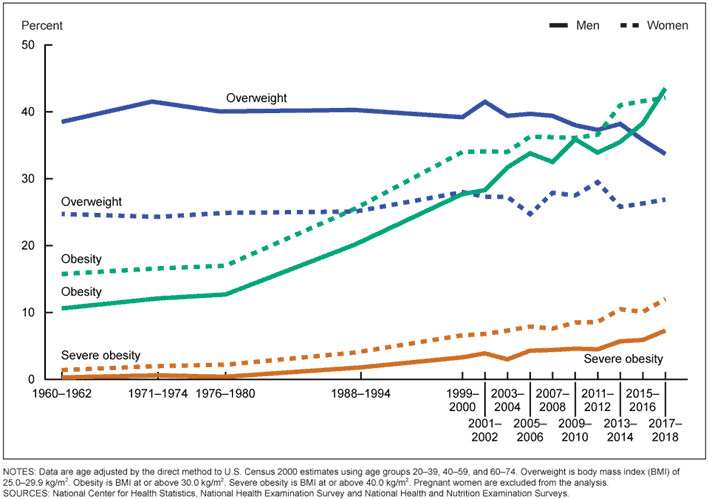

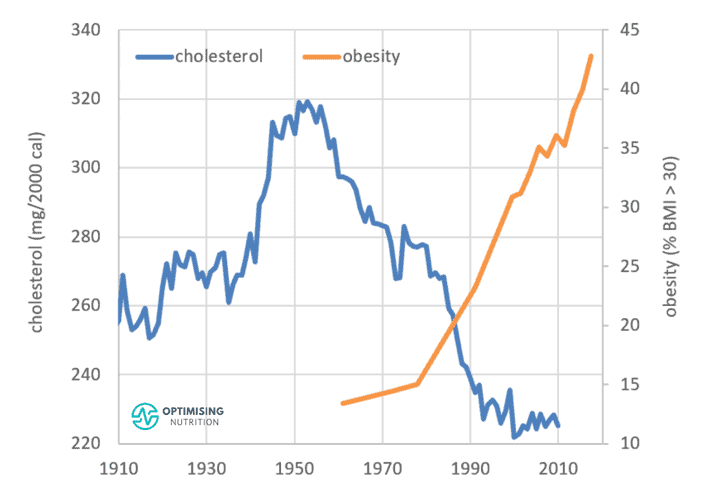

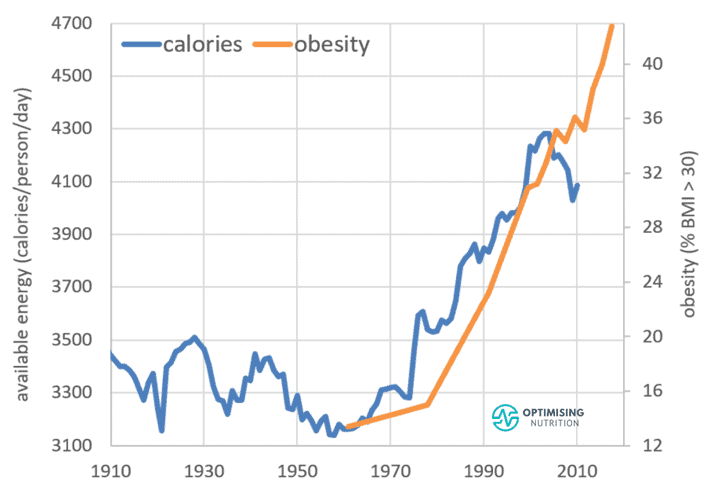

The chart below shows that obesity rates have risen from around 10% in 1960 to 43% in 2018! Something has changed! Many people have different theories on why this change has occurred in such a short time. This is mine.

How Did We Get Here?

Let’s start the story by looking at how food production and obesity have changed over the last century.

The period between the American Civil War and the start of the 20th century was a time of rapid technological innovation and industrialisation. The first fifty years of the 20th century were dominated by some unpleasant global events, including:

During this time, nutrition was more about quantity over quality; the focus was on feeding armies and optimising food production to provide for the masses with limited resources. As you can see in the chart above, the energy available in the food system was dwindling to dire levels in the 1960s. But by leveraging technological innovation, we learned to do more with less.

After some lean years through The Great Depression and World War II, when food was much harder to come by, America became the wealthiest country in the world. By the 1960s, the US population was a bit like a starving man who stumbles into an all-you-can-eat buffet!

You really can’t blame the leaders and technological wizards of the time for doing everything they could to maximise food production at any cost.

What Are the Most Important Topics in Nutrition?

You’ve likely heard parts of this story before, so I’ll keep it brief.

- In the 1950s, coroners found plaque build-up in the arteries of troops that was assumed to be from dietary cholesterol. Of course, we now understand that dietary cholesterol doesn’t equate to blood cholesterol or arterial plaque, but cholesterol and saturated fat in food became scapegoats at the time.

- Although heart disease rates had risen for a while, cholesterol became public enemy number one after President Eisenhower’s 1955 heart attack.

For more on cholesterol, check out Cholesterol: When to Worry About It and What to Do About It.

- Ancel Keys’ high-profile Seven Countries Study began in 1956. It pointed to dietary fat as the primary culprit for heart disease.

- In 1977, the Dietary Guidelines for The United States were published, recommending:

- less fat,

- less cholesterol from fatty meats, eggs, and dairy products,

- less refined and processed carbohydrates, and

- more fibre from fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

- At this point, Americans and some of the world had cut their dietary cholesterol intake to record lows. The US population’s dietary cholesterol intake has been falling since the 1950s (as shown in the chart below). But unfortunately, obesity rates continued in the other direction.

- Toward the end of the Vietnam War, food prices soared due to high inflation. With an election imminent, President Nixon appointed Earl Butz as Secretary of Agriculture with a mandate to reduce the cost of food. So, rather than rotating crops and letting farmers’ fields rest in between harvests, Butz pushed farmers to plant up their entire farm ‘from hedgerow to hedgerow’ and ‘get big or get out’ to deflate food prices.

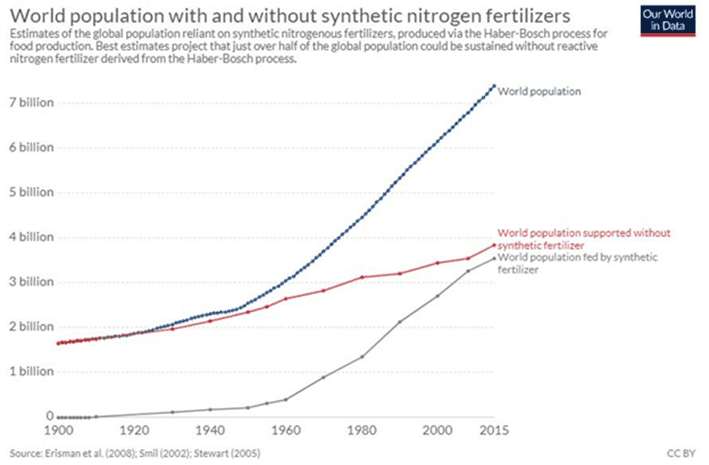

- In 1905, two genius chemists, Harber and Bosh, were awarded the Nobel Prize for working out how to create ammonia-based synthetic fertilisers powered by methane. This technology was used initially to create explosives during WW1. But around 1930, farmers started to increase their use of fertilisers to produce more food in less time.

- The impact of this technology cannot be understated. As shown in the chart below, it is estimated that nearly half of the current global population would not exist if it were not for the extra food that this technology facilitated.

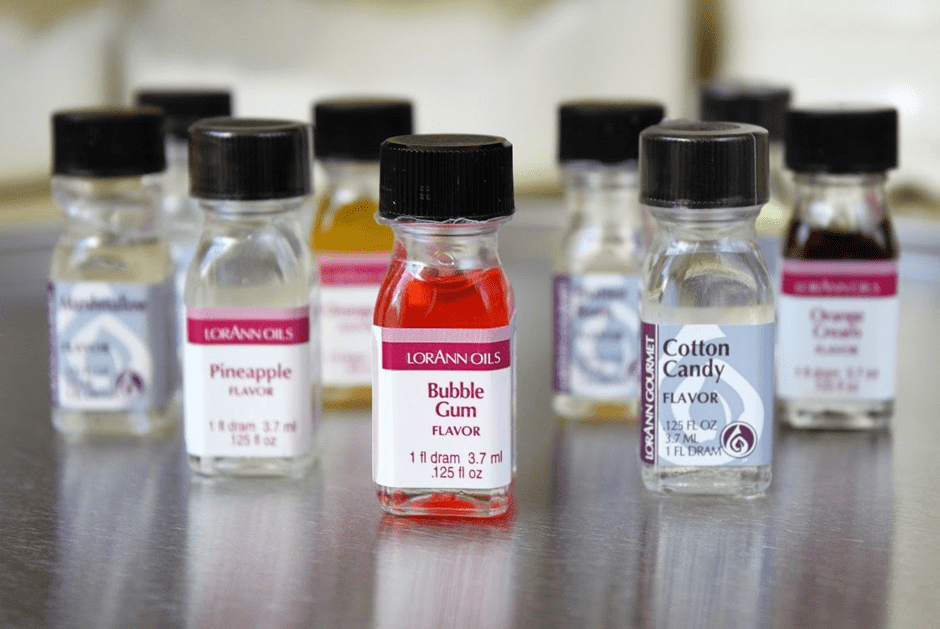

- While fast-growing, industrialised plants and animals provided plenty of energy, neither had the same nutrient content nor did they have the same flavour. The processed food industry teamed up with chemical engineers to optimise taste to address this problem. This quote from Mark Schatzer’s The Dorito Effect summarises the development of flavour technology quite well, although it’s a bit disturbing:

‘For millions of years, it worked perfectly. It helped us balance our nutrition so that we could find the foods we need, get what we needed and not eat to excess.

‘That all changed in the mid-1950s when the first gas chromatograph went on sale. Before that, scientists had absolutely no idea where flavour came from. They knew a lot at this point about things like the macronutrients, protein, carbs, and fat. But flavour was a mystery because flavours exist in such minute amounts.

‘With the gas chromatograph, you could take a piece of food and literally turn it into a gas. You volatize it and send the gas through this big coil. The coil separates every compound out.

‘Out the other end comes a flavour chemical, and then they would analyse it. It didn’t take long for them to analyse the flavours in things like fried chicken, tacos, tomatoes, or cherries. Then, they started making flavours in flavour factories.

‘They started putting them in foods… Junk food is a high-calorie, nutritionally empty food, that is true. But here’s the thing; we wouldn’t eat that stuff if not for the flavour. That’s what was added to make it irresistible.’

Mark Schatzker, The Dorito Effect

If you’re interested in hearing more from Mark, check out the podcast episode The End of Craving I recorded with him.

- Food manufacturers no longer needed the food they sold to contain nutrients. Instead, food scientists could take cheap energy from plants and animals grown quickly with the help of fossil-fuelled fertilisers and slap their new flavour technology on it for a profit. Voila! An effective workaround to the appetite cues developed by millions of years of evolution. What could go wrong?

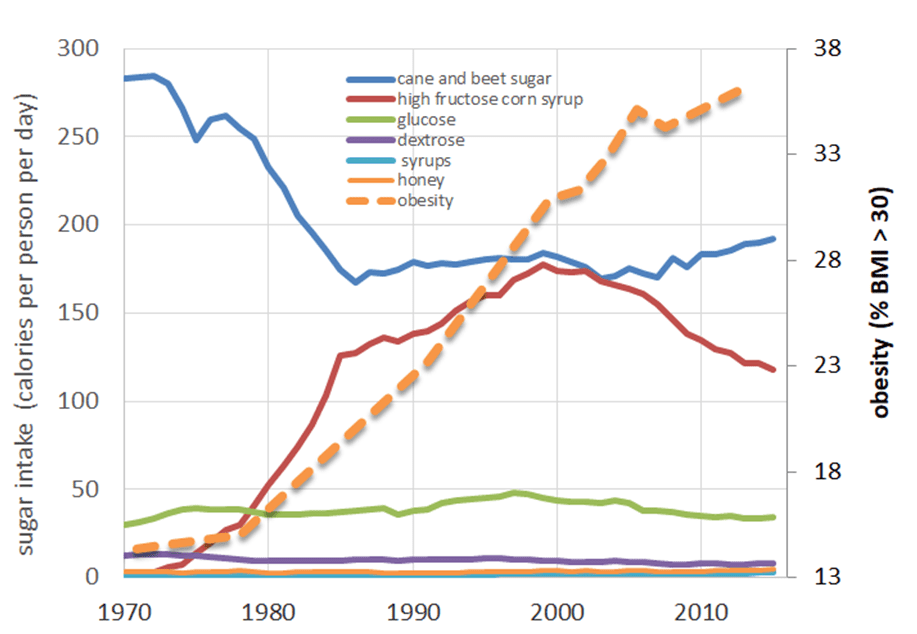

- In the late 60s, food scientists created High-Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS) from the overflow of subsidised corn. HFCS is similar to sucrose in the number of single sugars it contains. The significant difference is that glucose and fructose are free in HFCS rather than being bound together like sucrose.

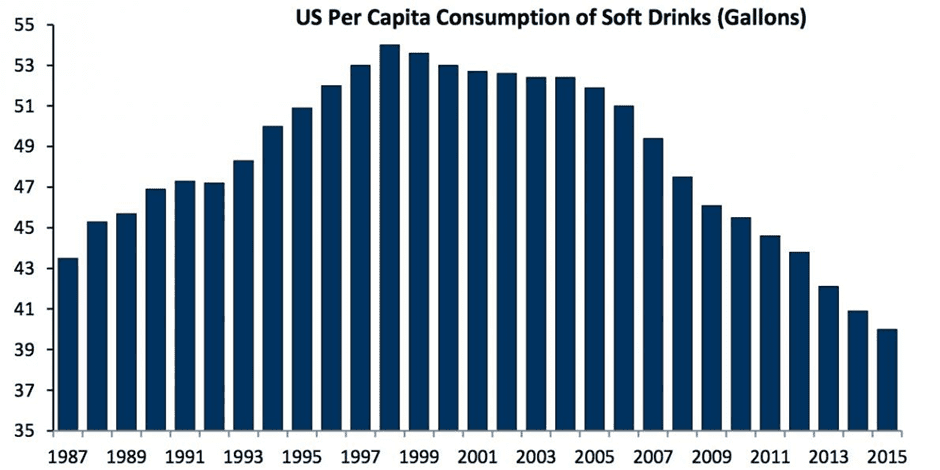

- Until soft drinks began to fall out of favour in 1999, more HFCS was consumed than cane or beet sugar.

- In 1992, Robert Atkins published his ground-breaking New Diet Revolution, which made many cautious of carbohydrates and less fearful of fat. In response, the food industry did what any intelligent for-profit organisation would do: it pivoted and gave the public more taste with less sugar. Now the energy was from fat from industrial seed oils, flavoured by artificial sweeteners rather than HFCS.

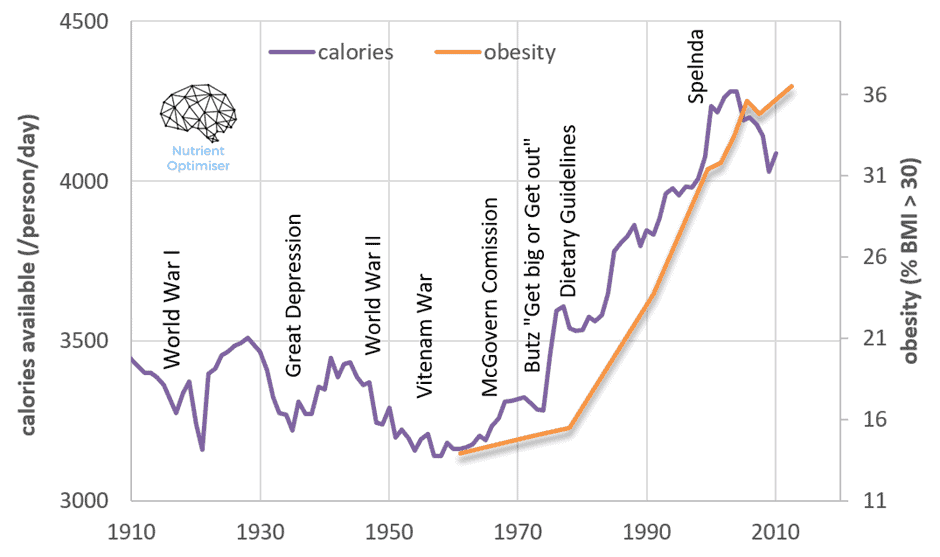

- In 1999, Splenda (or sucralose) was approved by the FDA. It didn’t take long before it had taken over the market, replacing HFCS in soft drinks and foods. The chart below shows the explosion of products containing artificial sweeteners.

- There are diverging opinions on whether artificial sweeteners cause weight gain independent of calories. But, regardless, foods full of chemical sweeteners and flavours optimised for bliss points stimulate the reward centres in your brain and are easier to overeat.

For more on how industrialisation has changed our food supply, check out What Lies Beyond the Nutritional Apocalypse?

While the low-carb movement won the battle against sugar in 1999, we’re all still losing the war against obesity. Thanks to the advances in modern agriculture, processing, flavour technology, and artificial sweeteners, today’s foods are still chock full of energy and flavour, which makes us want to eat more of them.

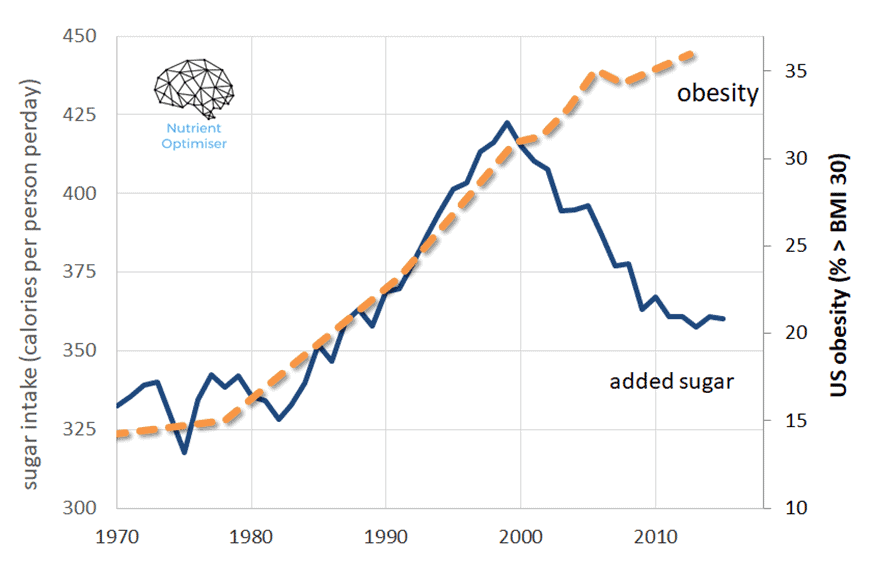

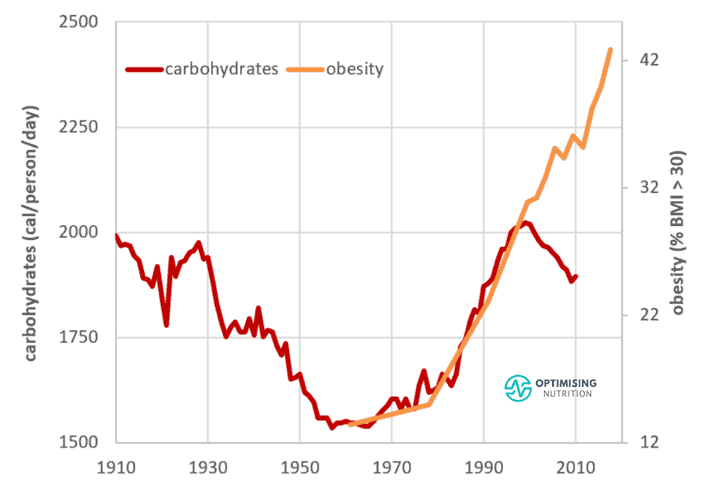

The chart below shows that carbohydrate availability over the past century dropped, increased, and then dropped again when artificial sweeteners were introduced, which displaced sugar in our food system.

Despite reducing carbohydrates two decades ago, obesity has powered on.

But if it’s not the sugar, HFCS or carbohydrates, why are we eating more than ever before and continually getting fatter?

Macro Trends in Nutrition

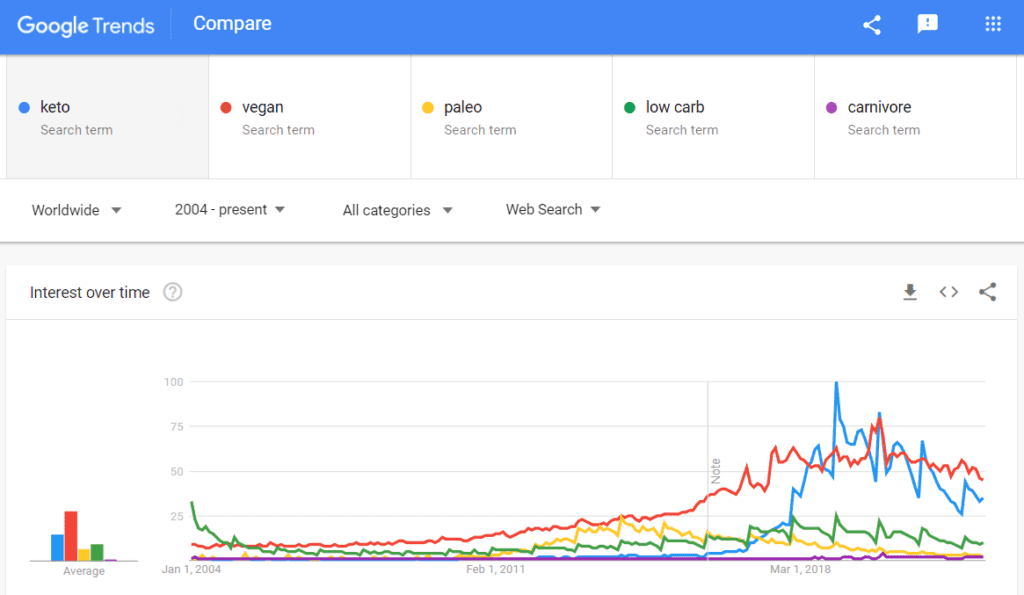

While our minds might jump to keto, paleo, or vegan when we think of ‘what’s in’ in terms of diet, we see some common trends with regard to what’s inside the foods we’re eating.

Let’s explore a few and how they relate to the obesity epidemic. First, let’s look at how macronutrients have changed.

Macros

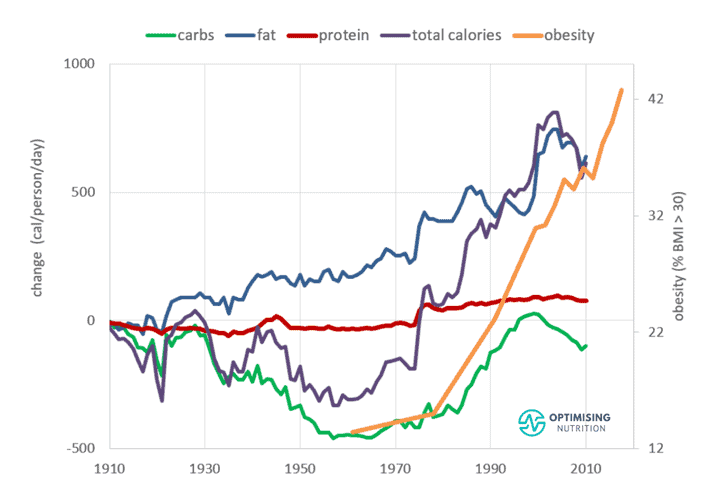

The chart below shows us that:

- protein content has been relatively stable;

- carbohydrates dipped and recovered to the levels they were at the start of the century; but

- fat has trended steadily upwards over time.

While the energy available from carbs has varied, obesity rates have tracked closely with total energy availability (purple line) since the 1960s, when obesity rates started to be measured.

‘Good Fats’ vs ‘Bad Fats’

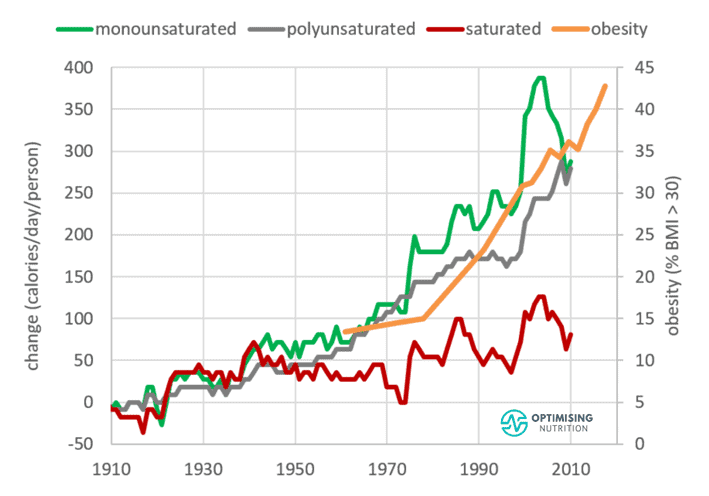

Contrary to what we’ve been led to believe, our production of saturated fats has only risen slightly in the past hundred years. However, the supply of fats deemed ‘good’ and ‘healthy’ from polyunsaturated sources like soy and corn has increased much more.

Saturated fat as a percentage of calorie intake has been dropping since the 1930s. It’s not that I believe saturated fat is good and can be eaten in unlimited quantities, but it doesn’t appear that it is the smoking gun of the obesity epidemic that it is often made out to be.

During the fifties and onwards, polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats from cheap vegetable oils replaced saturated fats like butter and animal lard in our diet for millennia.

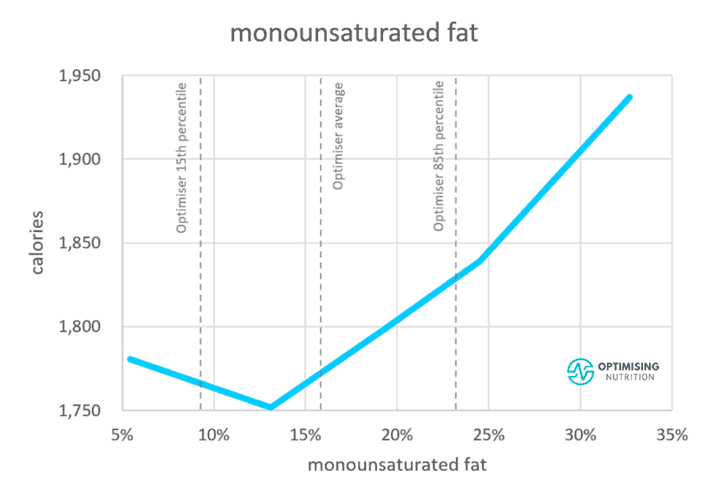

Our satiety analysis has shown these polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats have an inverse relationship to satiety. So, it’s no wonder more people have begun to question how ‘heart healthy’ they are for us, especially when they come as industrial seed oils added to ultra-processed foods.

Ironically, these fats produced from industrialised agriculture are cheap to make and easy to profit from. If you were cynical, you might think that the widespread demonisation of saturated fat and the promotion of unsaturated oils was a ploy to get you to eat more of the ultra-processed foods that are ultra-cheap to manufacture.

Micronutrients

Next, we come to the change in micronutrients, where things get interesting.

As you will see, the availability of many essential micronutrients in our food system has plummeted with the rise in industrial agriculture.

We now need to consume a lot more food to get the same amount of critical micronutrients.

Potassium

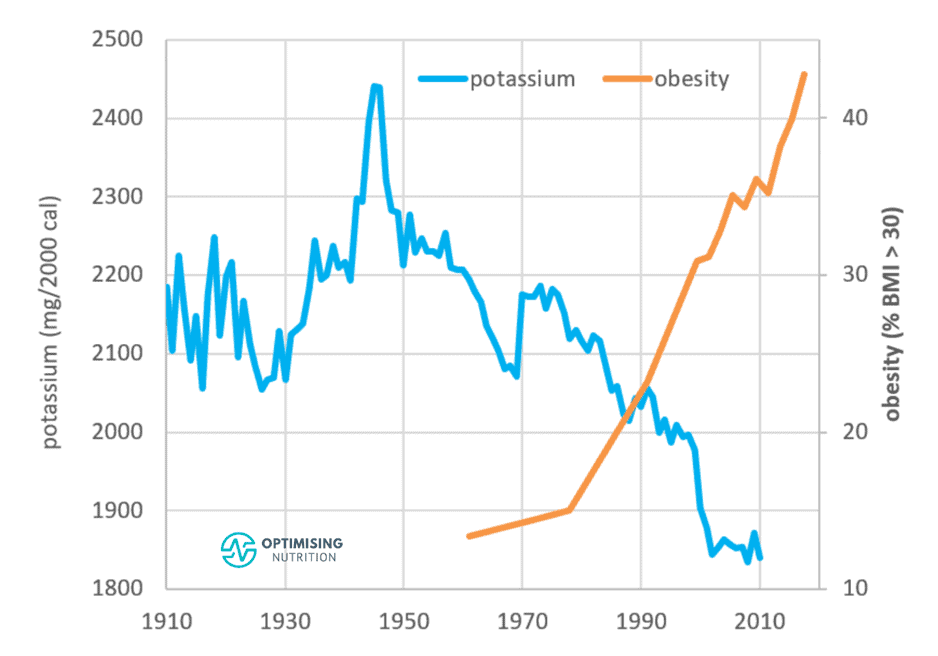

Potassium has been declining within our food system since chemical fertilisers made from liquid natural gas became more widespread. This nutrient has been deemed ‘a nutrient of public health concern’ because so many of us struggle to get enough of it.

To get your recommended minimum potassium intake (4700 mg/day) from readily available foods, you would need to eat around 5000 calories.

For more on potassium and where to find it, see High-Potassium Foods and Recipes: A Practical Guide.

Sodium

Sodium has been vilified for its role in hypertension and cardiovascular disease. But is potassium’s antagonist or the mineral that balances it? Thus, too much sodium can lower potassium levels. We’re only now beginning to recognise that hypertension has more to do with too little potassium than too much sodium.

Sodium is an essential nutrient, and we need some to survive! The sodium-potassium pump is vital for energy production. Hence, having enough of both nutrients is critical if we want to thrive.

The chart below shows how the sodium in our food system has declined since the 1960s. Interestingly, the rise in obesity correlates most closely to the reduction in sodium within our food system!

For more on sodium in food, check out Sodium in Food: A Practical Guide.

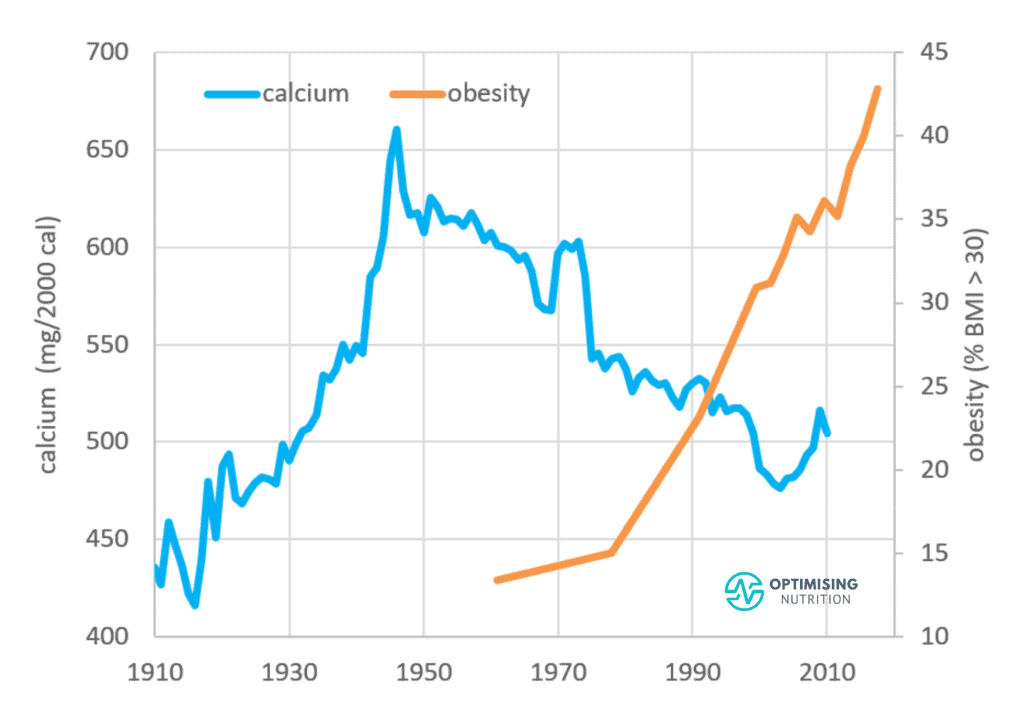

Calcium

Since we began our widespread use of fossil fuel-based fertilisers, the calcium content of our soils has also steadily decreased. We also consume less of foods like dairy products and green leafy veggies that contain substantial amounts of calcium.

To hit the RDI for calcium of 1.3 grams recommended for a healthy heart and skeletal function, you must now consume 5500 calories per day! Unfortunately, calcium supplements aren’t as effective as calcium from whole foods.

To read more about calcium and what it does for you, visit Healthy High-Calcium Foods and Recipes.

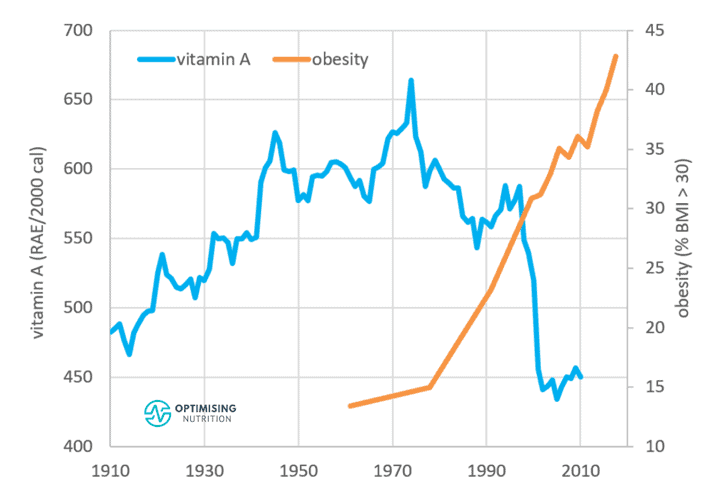

Vitamin A

We require the fat-soluble nutrient vitamin A for normal vision, reproduction, development and immune function. The bioavailable form of this nutrient, retinol, is found abundantly in liver, fish, eggs, and dairy products.

Data from the USDA shows that it has decreased substantially in our food system since the 1977 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

Ironically, foods that contain vitamin A also often contain saturated fat and cholesterol. These foods were not part of the USDA’s farm-centric agenda that emphasised ‘heart-healthy’ ‘whole grains’.

To get the recommended daily intake (DRI) of vitamin A from foods available in the modern food system, you’d need to eat around 2650 calories. In comparison, you’d only need to consume about 1550 calories daily in the mid-70s.

For more on vitamin A, visit Vitamin-A Rich Foods and Recipes: A Practical Guide.

Phosphorus

Phosphorous is a mineral found in protein-rich foods like meat, poultry, fish, nuts, beans, and dairy products. Since the 1940s, it’s been steadily decreasing within our food system. Plant-based sources of phosphorus are much less bioavailable than animal-based sources.

To get the phosphorus RDI of 1000 mg per day, you’ll need to eat far more calories from foods today to get the same amount of phosphorus as you would in the 1970s.

For more on phosphorus, visit High-Phosphorus Foods and Recipes.

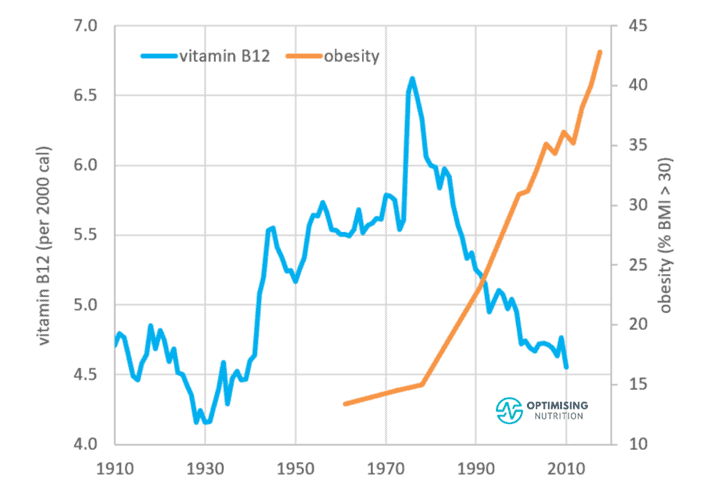

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 is a nutrient found almost exclusively in animal products that is critical for neurological function and energy production. Since the 1970s, it has also decreased substantially within our food system.

For more on B12, visit Highest B12 (Cobalamin) Foods and Recipes.

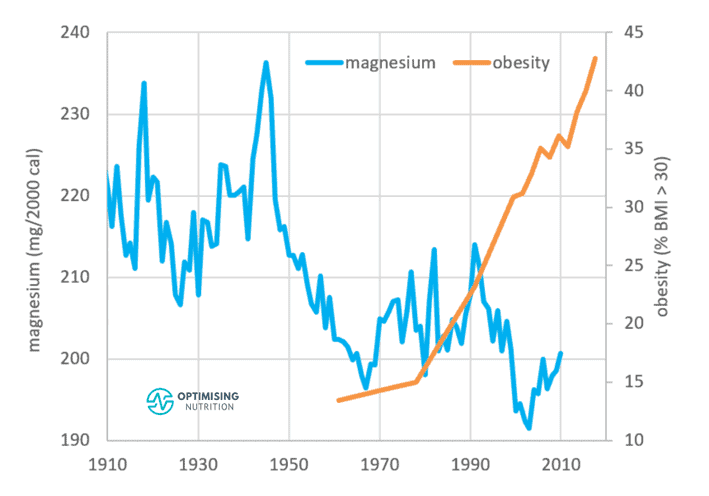

Magnesium

It’s hard to overstate the importance of magnesium, which works with other minerals to produce energy, relax muscles, and send nerve signals (amongst other things).

Since we started relying more heavily on fertilisers to expedite crop growth, magnesium also seems to have declined. You must now consume more than 4,000 calories per day to get your daily dose of magnesium.

For more, check out Magnesium-Rich Foods and Recipes: A Practical Guide.

Correlation Analysis

While correlation doesn’t mean causation, the table below shows the change in a range of nutrients with obesity rates. The decrease in nutrients towards the top of this table is correlated most strongly with the increase in obesity.

| Nutrient | correlation |

| sodium (g/2000 cals) | -96% |

| calcium (g/2000 cals) | -96% |

| cholesterol (g/2000 cals) | -96% |

| saturated fat (%) | -92% |

| potassium (g/2000 cals) | -91% |

| vitamin A (RAE/2000 cal) | -81% |

| phosphorus (g/2000 cal) | -80% |

| vitamin B12 (mcg/2000 cal) | -70% |

| magnesium (mg/2000 cal) | -33% |

| vitamin C (g/2000 cals) | -3.4% |

How Much Do You Need to Eat to Get Enough Nutrients?

The table below highlights some of the nutrients we are getting less of, along with the maximum and minimum amount available in the food system over time from the above charts. The right-hand column shows how much extra we would need to eat to get the minimum amount of these nutrients.

| Micronutrient | Max | Current | DRI | extra calories |

| Vitamin A | 980 | 680 | 900 | 32% |

| Calcium | 660 | 480 | 1300 | 171% |

| Potassium | 2440 | 1835 | 4700 | 156% |

| Sodium | 780 | 495 | 2000 | 304% |

| Magnesium | 236 | 191 | 420 | 120% |

| Phosphorus | 1030 | 890 | 1000 | 12% |

Without improving the nutrient density of the foods you eat, you’ll need to consume a ton of extra energy to get enough of these key nutrients.

To get the amount of vitamin A you require, you would need to consume an extra 30% of total calories, nearly 170% extra to get sufficient calcium, 160% extra to get adequate potassium, and 120% extra to get the magnesium you require.

Summary

- The industrialisation of the food system since the 1960s means we have more food available. This has allowed us to support a larger population of larger people. However, due to the decrease in nutrient density, we need to consume more energy than before to get the nutrients we need, including vitamin A, vitamin B12, phosphorus, calcium, potassium, sodium, and magnesium.

- Similar to the Protein Leverage Hypothesis, it is likely that micronutrient leverage is at least a partial contributor to the significant increase in energy consumption that we’ve seen over the past four decades.

- As nutrient density declines, our appetite ramps up, and we consume more food than we otherwise would to obtain the nutrients we need to thrive.

There is another significant source of easily absorbed iron. All flour in the US is fortified with iron. Everyone gets extra iron with every food and snack item. Iron is stored as ferritin in liver, bone marrow, and shows up as serum ferritin in the blood. Ferritin in the US is very much higher than in most other countries.

This is so very fascinating, and necessary. Thank you for doing the work!

This is an excellent summary. Thank you!

Is cornivore a typo (on Google graph), or is there a new corn-based fad diet I haven’t heard of?

😉

good pickup! fixed.