Dive into a thorough analysis of how the insulin response to protein compares to that of carbohydrates, a subject crucial for individuals with diabetes or anyone endeavouring to manage their blood sugar levels effectively.

Through an in-depth examination of the food insulin index data, this article demystifies the effects of protein on blood glucose levels, providing actionable insights for those keen on optimizing their nutritional strategies for better health outcomes.

- Highlights

- Background

- The blood glucose response to protein

- The insulin response to protein

- Diabetic versus normal response to protein

- What happens when we eat a lot of protein?

- Do amino acids spill over into glucose in the bloodstream?

- Glucagon response

- Glucagon, the antidote to insulin?

- Letting your pancreas keep up

- The high protein ‘hack’ for diabetics

- What is the optimum amount of protein and carbohydrates?

- More

Highlights

- The food insulin index data indicates that blood sugar and insulin respond to the glucogenic component of protein. [1]

- A higher protein intake leads to better blood sugar control, increased satiety and reduced caloric intake.

- Digested amino acids from protein circulate in the bloodstream until they are required for protein synthesis, gluconeogenesis or the production of ketones.

- The release of glucose from protein via gluconeogenesis is a demand-driven process that is smoother and slower than carbohydrates.

- Someone who is insulin resistant and/or whose pancreas is not producing adequate insulin may benefit from higher protein with lower carbohydrate (LCHP) to smooth out the blood sugar response while still obtaining adequate protein.

Background

Protein doesn’t significantly raise blood sugars, at least compared to carbohydrates.

At the same time, it is generally acknowledged (at least by people with Type 1 Diabetes) that protein requires insulin to metabolise. Managing the blood glucose response to protein is a challenge for diabetics, particularly if they are minimising carbohydrates and hence may have a higher protein intake.

Recently, an increasing number of people trying to achieve nutritional ketosis have found that they need to moderate protein in addition to limiting carbohydrates to reduce insulin to the point where significant levels of ketones can be measured in the blood.

My aim here is not to criticise protein but rather to better understand the insulin and glucose response to the protein in light of the food insulin index data.

My wife Monica has Type 1 Diabetes. So any information that can help refine insulin dosing or help inform food choices that will lead to more stable blood sugars is of interest to me.

I have a family tendency towards obesity and pre-diabetes (based on my 23andMe testing and a lifetime of personal experience trying to keep the weight off), so I am also interested in how I can optimise my blood sugars and insulin levels. I would also love to dodge the weight creep that seems to come with middle age for most people.

This has been a challenging topic to get my head around. It is complex, and there is a lack of definitive research to provide clear guidance. Hopefully, more data and discussion can help to progress the theory’s understanding and practical application.

I do not claim to have all the answers, but plenty of observations and questions. I hope I can help move this discussion forward by documenting some of these.

The blood glucose response to protein

The food insulin index data contained in Clinical Application of the Food Insulin Index to Diabetes Mellitus by Kirstine Bell (Sept 2014) [2] intrigues me. There is a lot to be learned from looking at the body’s insulin response to food and the interrelationship to other parameters such as fat, protein, carbohydrates, fibre and blood glucose.

The data points on the right-hand side of the chart below [3] indicate that high protein foods (e.g. fish, tuna and steak) cause a small rise in blood glucose. However, the blood sugar response to protein is still small relative to the high carbohydrate foods on the left-hand side of the plot.

For most people, the discussion ends there. Protein does not raise blood sugar much; therefore, it is a non-issue. !

But is it really that simple? What does the expanded food insulin index data set tell us?

The insulin response to protein

One of the challenges I see for type 1 diabetics is that, even if they eat a low carbohydrate diet, they still struggle with blood sugar control after a high protein meal.

Type 1s who have a continuous glucose monitor know that they need to watch out for a rise in their blood glucose three or four hours after a high protein meal and use correcting insulin doses to keep their blood sugar from going too high.

Looking at the protein versus insulin index plot below, we can see that the insulin response to protein is more significant than the blood glucose response to protein.

For instance, the insulin index score for whitefish is 42%. However, it only receives a 20% glucose score (note: the percentage scores are relative to pure glucose, which has a glucose score and a food insulin index score of 100%).

Maybe something is going on that can’t simply be explained by the blood sugar response alone.

If we plot the glucose score versus the insulin index, we see that glucose and insulin are not directly proportional.

Low-carbohydrate, higher-protein foods such as chicken, cheese, tuna and bacon require a lot more insulin than would be anticipated if insulin was directly proportional to the blood glucose response.

On the lower side of the trend line, we have high carbohydrate foods from whole food sources such as raisins, wholemeal pasta, brown rice and water crackers having less of an insulin response than would be anticipated from the blood glucose response.

Diabetic versus normal response to protein

The figure below compares the blood sugar and insulin response to 50g of protein (200 calories) in type 2 diabetics (yellow lines) and healthy non-diabetics (white lines). [4] We can see that:

- Blood glucose remains relatively stable for healthy people after eating 50g of protein. However, when someone with Type 2 Diabetes eats a high protein meal, the insulin secreted seems to bring the blood sugar down from elevated levels!

- Insulin is elevated for more than five hours after ingestion of protein, particularly for the insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic. There’s something going on with insulin in response to high-protein foods, even if we don’t see a sharp increase in blood sugar.

- The diabetic requires a lot more insulin to deal with the same quantity of protein, and it takes a lot longer for the insulin levels to peak and comes down.

We can also see from the insulin response that protein takes more than three hours to digest and metabolise. It is possible that the food insulin index data (which is based on the measurement of insulin over only three hours) underestimates the insulin response to protein-containing foods and that the insulinogenic demand of protein is higher than predicted by the food insulin index data (i.e. protein requires more than 56% of the insulin relative to carbohydrate).

What happens when we eat a lot of protein?

The question of what happens to ‘excess’ protein that is not required for muscle growth and repair is controversial, and the science is not exactly clear.

Does the energy from unused protein magically disappear? If it did, then protein would be the ultimate macronutrient that everyone should eat to lose weight. We could effectively ignore calories from protein.

Does it turn into nitrogen and get excreted in the urine?

Or does it turn into glucose ‘like chocolate cake’?

There is limited authoritative information on this topic. However, some helpful guidance that I’ve found on the subject is outlined below:

- Richard Feinman says that “…after digestion and absorption, amino acids not used for protein synthesis may be trashed. The nitrogen is converted to ammonia which is converted to urea and excreted. The remaining carbon skeleton can be utilized for energy either directly or converted to ketone bodies, particularly on a very low carbohydrate diet.” [5]

- Richard Bernstein says, “Dietary protein is not the only source of amino acids. The proteins of your muscles continually receive amino acids from and return them to the bloodstream. This constant flux ensures that amino acids are always available in the blood for conversion to glucose (gluconeogenesis) by the liver or to protein by the muscles and vital organs.” [6]

- According to David Bender, “In fasting and on a low carbohydrate diet as much of the amino acid carbon as possible will be used for gluconeogenesis – an ATP-expensive, and hence thermogenic, process.” [7]

So it appears that amino acids circulate in the bloodstream and can be used as required for protein synthesis or to stabilise blood glucose levels.

The figure below [8] shows a comparison of the blood glucose response to ingestion of glucose and 600g of lean beef (i.e. a huge serving of steak!).

During the more than eight-hour period that the steak takes to digest, you can see the nitrogen levels continue to rise. Meanwhile, blood glucose rises only slightly until around four hours after the meal and comes back down.

What appears to be happening here is that the amino acids from digestion are being progressively released into the bloodstream (over a period of digestion of more than eight hours) but are not immediately converted to blood glucose. Thus the digestion of protein does not cause a sharp rise in blood glucose.

It is said that gluconeogenesis is a demand-driven process, not a supply-driven process. What I think this means is that the body can draw on the amino acids circulating in the bloodstream for muscle growth and repair (protein synthesis) or to balance the blood sugar (via gluconeogenesis) depending on requirements from moment to moment.

The fact that we don’t see a sharp rise in blood glucose in response to protein indicates that excess protein does not immediately turn into glucose. Gluconeogenesis occurs slowly over time, with the amino acids being used up as required.

However, as noted by David Bender above, if we are fasting or minimising carbohydrates, then our body will maximise the use of protein to produce glucose via gluconeogenesis. Conversely, if we eat more carbs and less protein, the body doesn’t need to rely on protein as much for glucose.

Do amino acids spill over into glucose in the bloodstream?

Most people aren’t eating so much protein that their amino acid stores in their blood are full to overflowing like peoples’ livers and are typically overflowing with glucose from a higher carbohydrate diet.

It would be interesting to see what happens in someone whose bloodstream became saturated with amino acids from long-term consistently high protein consumption.

Would we see more protein excreted or perhaps a larger amount removed from the blood via gluconeogenesis with subsequent conversion to fat using insulin?

By comparison, when carbohydrate is eaten, we typically see glucose causing an immediate rise in blood sugar because the liver is often already full.

Glucagon response

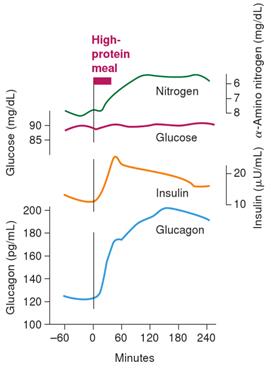

A healthy non-diabetic person will release both insulin and glucagon in response to a high-protein meal.

Insulin helps to metabolise the protein and grow and repair muscles (i.e. insulin is ‘anabolic’). Glucagon helps to keep blood sugar stable and prevent it from going too low due to the action of the insulin used in the muscle growth and repair process.

The body secretes glucagon and insulin in response to a high-protein meal (as shown in the figure below [9]). In a healthy insulin-sensitive non-diabetic person, the glucagon will cancel out the insulin response to the protein used for protein synthesis. Hence we see a flat line blood glucose response in the insulin-sensitive non-diabetic.

In a diabetic, particularly type 1s, we often see blood sugar rising after a high protein meal due to the initial glucagon response and then gluconeogenesis as some of the protein converts to glucose. In the diabetic, the insulin response is either inadequate (due to poor pancreas function) or ineffective (due to high insulin resistance) and therefore the blood sugar does not remain stable as it would in a metabolically healthy person.

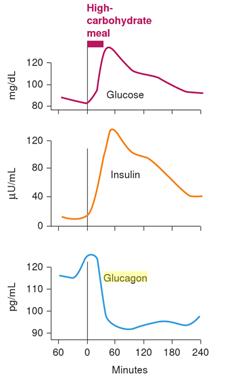

By contrast, after we eat a high carbohydrate meal, glucagon decreases as the insulin increases, and the body moves into fat storage mode, as shown in the following figure. [10] The primary thesis of Protein Power is that we want to do whatever we can to maximise glucagon, which promotes fat burning, rather than insulin which leads to fat storage.

Even though glucagon offsets the insulinogenic effect of protein used for protein synthesis, it seems that the glucogenic portion of protein requires insulin.

I haven’t found any data on the subject, but I wonder if the body does not secrete glucagon to negate the effect of the ‘excess’ protein over and above the body’s requirement for protein synthesis (say 7 to 10% of calories)?

If this were the case, will the glucogenic proportion of excess protein behave largely like a carbohydrate with no glucagon to counteract the insulin.

Glucagon, the antidote to insulin?

The observation that glucose does not rise significantly in response to protein is often taken to mean that protein is a non-issue. [11] [12]

This may be largely true for someone who is insulin sensitive. However, diabetics with impaired pancreatic function may not be able to secrete adequate insulin to offset the effects of glucagon and keep their blood sugars stable.

If you are a type 2 diabetic or someone with impaired insulin sensitivity, I suggest that it would be better to keep your carbohydrate AND protein intake to the point where your body can keep up and maintain normal blood sugars.

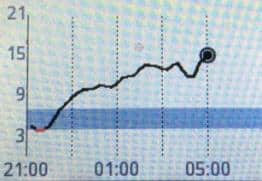

The image below shows the continuous glucose monitor (CGM) plot of a type 1 diabetic after ingestion of a protein shake (46.8g protein and 5.6g of carbs).

Without insulin, there is a blood sugar rise over more than eight hours, not dissimilar to what you would see from carbohydrates.

Is this blood glucose rise from gluconeogenesis of the protein or is the blood glucose rise from glucagon in response to the ingested protein or a bit of each? It’s hard to know.

What we do know is that there is a rise in blood glucose that needs to be managed if we are going to achieve optimal blood sugar control.

Letting your pancreas keep up

For a diabetic who is insulin resistant and/or whose pancreas is not producing adequate insulin, the issue is that the total insulin load of their diet (from carbohydrates and the glucogenic component of protein) is more than their body’s ability to keep blood glucose under control.

From the insulin index data, we know that the body’s blood sugar and insulin response are proportionate to carbohydrates plus about half of the ingested protein.

So potentially, we can balance our blood glucose response by managing the glucogenic inputs, that is, by moderating protein and keeping carbohydrates adequately low. And by doing this, we can minimise, or perhaps eliminate, the need for insulin or other medications.

The high protein ‘hack’ for diabetics

To some extent, obtaining glucose from protein rather than carbohydrate is a beneficial ‘hack’ for someone who is not able to manage their blood sugars given:

- eating higher levels of protein will ensure that the body’s needs for essential amino acids are met or exceeded;

- the blood sugar rise from protein is much slower than it is for carbohydrate foods, and hence it is easier to keep blood sugars under control;

- protein takes more energy to convert to glucose than using carbohydrates directly. Hence, additional energy is lost in the process (i.e. a calorie of protein is not really a calorie if you have to convert it to glucose before it can be used), [13] and

- protein is more satiating than carbohydrates.

Paul Jaminet argues that obtaining glucose from protein is not ideal, given that it’s not as energy efficient as getting it directly from carbohydrates.

However, I think that the optimal approach is to ensure that you maximise vitamins, minerals, fibre and amino acids from carbohydrate and protein-containing foods while at the same time not overwhelming your body’s ability to maintain optimal blood sugars due to excess glucose from either carbohydrate or excess protein.

To some extent, it’s a balancing act between gaining adequate nutrition from things that will raise blood glucose while at the same time not overwhelming the ability of your pancreas to produce insulin to keep blood sugars in the ideal range.

The food ranking and meal ranking systems have been designed around this approach.

What is the optimum amount of protein and carbohydrates?

I find Steve Phinney’s well-formulated ketogenic diet chart helpful when it comes to understanding how to optimise protein and carbohydrate intake.

- The minimum protein intake is around 10% of calories or 0.8g/kg body weight. [14] At this point, the vast majority of the protein will go to muscle growth and repair. Based on the guidance given by the WFKD triangle, you might even be able to tolerate up to 20% carbohydrates and stay in nutritional ketosis if you were to keep your protein levels low. At this point, you won’t have to worry too much about gluconeogenesis messing up your blood sugars because all of the protein will be used up in protein synthesis.

- If you are active, then you will likely want higher levels of protein, with 1.2 to 1.7g/kg body weight recommended for athletic performance. [15] Higher levels of protein will ensure that you have enough amino acids for optimal physical and mental function rather than just being adequate.

- As we move to higher levels of protein above the minimum 10% of calories, we should also consider reducing carbohydrates and increasing fat because the glucogenic portion of the protein that is over and above the basic needs for growth and repair will likely be turned into glucose, requiring increased levels of insulin which will work against you if your goals are reducing your insulin load to stabilise blood sugars or to lose weight.

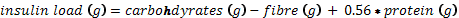

If you are keeping track of your food intake, you can use the formula below to calculate and track your insulin load.

If you are not yet achieving normal blood sugar levels you could try winding back your insulin load. Most people find that they will achieve stable blood sugars and nutritional ketosis with an insulin load of around 125 g. However, your mileage may vary, and you will likely have to tweak this level to find your optimum based on your goals and your situation.

More

References

[1] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glucogenic_amino_acid, https://www.dropbox.com/s/4dkl03mz2fci71v/The%20metabolism%20of%20%E2%80%9Csurplus%E2%80%9D%20amino%20acids.pdf?dl=0 and http://www.medschool.lsuhsc.edu/biochemistry/Courses/Biochemistry201/Desai/Amino%20Acid%20Metabolism%20I%2010-14-08.pdf

[2] http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/11945

[3] Glucose score is the area under the curve of the rise in blood glucose response over three hours relative to pure glucose tested in healthy non-diabetics.

[4] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC524031/

[5] Chapter 5 of The World Turned Upside Down: The Second Low Carbohydrate Revolution.

[6] Dr Bernstein’s Diabetes Solution, page 96.

[7] https://www.dropbox.com/s/4dkl03mz2fci71v/The%20metabolism%20of%20%E2%80%9Csurplus%E2%80%9D%20amino%20acids.pdf?dl=0

[8] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC424828/pdf/jcinvest00541-0071.pdf

[9] https://books.google.com.au/books?id=3FNYdShrCwIC&printsec=frontcover&dq=marks+basic+medical+biochemistry&hl=en&sa=X&ei=-ctaVcivOJfq8AXL84CAAw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=glucagon&f=false

[10] https://books.google.com.au/books?id=3FNYdShrCwIC&printsec=frontcover&dq=marks+basic+medical+biochemistry&hl=en&sa=X&ei=-ctaVcivOJfq8AXL84CAAw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=glucagon&f=false

[11] http://caloriesproper.com/dietary-protein-does-not-negatively-impact-blood-glucose-control/

[12] http://www.ketotic.org/2013/01/protein-gluconeogenesis-and-blood-sugar.html

[13] See chapter 15 of Richard Feinman’s The World Turned Upside Down: The Second Low Carbohydrate Revolution for an in depth discussion of this topic.

[14] This is based on the point where at least half of the population has adequate protein! Not exactly an ideal goal to be shooting for!

[15] https://www.dropbox.com/s/zelfo3n0q8kvtfx/Paoli%20et%20al.%20(2015)%20The%20Ketogenic%20Diet%20and%20Sport%20A%20Possible%20Marriage.pdf?dl=0

I think your work is brilliant and cannot thank you enough for it…however…I am an idiot because a lot of it might as well be in Greek for me. I am a retired nurse who just recently ditched 26 years of brittle diabetes by going extremely low carb. My issue is that if I get sick from others issues this poor old body suffers my sugars…even on less than 5% carbs and frequently none…is suddenly in the mid to high teens. I read you religiously because I am trying to find out why…and how this all works…but I am assuming you would have to dumb it down too much for folks like me. No worries, I will keep reading your wonderful work because…all evidence to the contrary…I am learning something from every post ! Thank you …

So glad to hear you’re enjoying the blog!

I have heard the term, but I have never seen “brittle diabetes” defined. I imagine it means you’re a type 1 with a completely exhausted pancreas and any carbs leaves you on an extreme blood sugar roller coaster.

Glad you’re learning something. I think the foods (https://optimisingnutrition.wordpress.com/2015/04/06/optimal-foods-for-blood-sugar-regulation-and-nutritoinal-ketosis/) and the meals (https://optimisingnutrition.wordpress.com/2015/03/22/recipes/ – a work in progress) will be the most practical application of the theory.

Thanks for the encouragement. Wish you the best on your challenging journey.

Good stuff here. Curious as to your thoughts on gut health?

Gut health is also a very important part of the picture. Reducing excess glucose will also go a long way to helping to balance gut bacteria.

Hi Marty

Despite being a type2 diabetic for 15 years I have only recently found out about the low carb way of controlling BGLs and even more recently found out that I need to take my protein consumption into account as well. I’ve spent the last 3 months reading and reading on the internet until my head is spinning.

Finding your blog has been a godsend. You have a knack of consolidating all that confusing (and often contradictory) info out there. My head is spinning less and my BGLs are coming down. I can more clearly see the path towards continuing improvements now.

Thanks for the help

Awesome. Thanks Carmel. The blog is my way to work through all the info and bounce it off people.

It frustrates me that there is such a lack of clarity for the people that need it so badly. I hope the blog can help address that.

I’m surprised that there are so many people that are interested in the longer more technical articles rather than just ‘what to eat to lose weight’.

I’m interested in the technical information because for the past 15 years I’ve been reading the “what to eat” books and have just ended up more and more unhealthy. Now I’m suspicious of everything and want to know “Why should I?!” Got to admit, the sciencey thing is just interesting too, and even kind of fun. Keep up the good work

Hi Marty I speak as a retired GP who spent nearly 50 years giving diabetics bad advice – along with just about all other doctors. Starting intermittent fasting in September 2013 at 108 kilos, I achieved my goal of 85 kilos in July 2014 and maintained it since. I’ve been under pressure to tell others how to do what I did. Preparing what to say in an authoritative manner, I’ve spent months discovering that the more I study the less I seem to know.

Here are some thoughts / observations:

Ketosis has been glorified

Fructose has been vilified.

I’m wary of extreme positions in medicine.

If it is true that neither Inuits nor polar bears are ketogenic, then ketogenesis is an extreme position in man.

Mind you, Type 1 diabetes is an “extreme” position in terms of it being invariably fatal before the discovery of insulin in 1921.

The fact that it takes weeks to keto-adapt but minutes to re-adapt to sugar suggests to me that sugar is OK at least for the otherwise healthy – in moderation.

Check out American Black Bears. They are omnivores who love honey. In case you think I am against ketosis, I note that bears can hibernate for up to 8 months a year living on fat alone.

It appears that Type 1 diabetics using insulin many times a day can eventually develop Type 2 diabetes as well. That really adds insult to injury.

This brings me to intermittent fasting:

Re type I diabetes: provided monitoring is tight, I think intermittent fasting could be part of the therapeutic approach. Having a rest from insulin kicks in a large number of beneficial mechanisms as I am sure you know.

Re Type 2 diabetes, some form of intermittent fasting should be, in my opinion, the treatment of choice before medications.

Going back to that “bad advice”. Just about every patient said to me: “I won’t have tablets yet doc. I’ll try diet”. I knew they would all fail, but that was because they all followed the Heart Foundation and Diabetes Australia’s advice, cut out fat and ate lots of bread and potatoes.

Finally I’d be most interested to know what happens to HbA1c in those type 1 diabetics who follow a slightly more relaxed approach to hyperglycaemia who simultaneously reduce their insulin requirement to next to nil twice a week by fasting.

Regards John Beaney

Hi John

Firstly, congrats!

I think I’m on the same page as you when it comes to fructose. Sugar alone appears to be a poor predictor of insulin response compared to non-fibre carbohydrates. See https://optimisingnutrition.wordpress.com/2015/04/27/is-sugar-really-toxic-2/

I also agree that therapeutic ketosis has been glorified.

I think ketosis and IF are different sides of the same coin. Both are about reducing the insulin load of the diet to restore insulin sensitivity. Both can be used to greater or lesser degrees depending on the requirement.

I know it was the IF that helped me break through my insulin resistance but I also enjoy a moderately low insulin load diet on a day to day basis with occasional IF.

I know type 1s who have seen significant reductions in their basal insulin and improvements in insulin sensitivity through IF.

Many type 2s are able to normalise blood sugars through IF which resets their insulin sensitivity and allows them to get off or avoid medication.

I also know that Bernstein advocates for small amounts of insulin for type 2s in addition to a low carb diet to ensure that they achieve optimal blood sugars.

Improving insulin sensitivity, normalising blood sugar levels and reducing insulin toxicity are all important.

It would be an interesting discussion to continue with the group at https://www.facebook.com/optimisingnutrition if you’re interested.

Cheers

Marty

Hi John – I found your comments very interesting.

One comment though: low carb means different things to different people, and likewise with intermittent fasting. Brad Pilon discusses the latter here: http://bradpilon.com/weight-loss/fasting-for-weight-loss-setting-the-record-straight/

Some go low carb, some go IF (eg Brad Pilon), and some like to combine both (eg Dr Jason Fung).

So, Dr Beaney, what sort of IF did you do? (eg 2 x 24 hour fasts per week – like Pilon and, more recently Mosley) and was it IF alone or did change what you ate as well? (+/- exercise).

Regards,

SL

Hi John,

I am a T1 diabetic and have had good results from doing the opposite of what the endocrinologist and diabetes association told me to do. Eat carbs and multiple times a day is ridiculous and only benefits the companies making the diabetic drugs.

Over a two year period, been able to lower my A1C from 13 to 5.4. I started by using variations of LCHF/Bernstein/Paleo type diets and they worked to some degree, but not well enough. The best results I have seen have been from implementing a ZC (zero carb) primal (95% raw/5% cooked or cured protein) keto (80% animal fat/20% animal protein) way of eating for a year, with IF/OMAD over the last six months (12:12 then 23:1 for last three months).

Occasionally when I would go low in the afternoon 5pm-6pm I would open my window early. One ounce of meat would raise my blood sugar from say 3.5 to 4.5; enough to get me through until I would eat at 9pm. Again misinformation from diabetes association that if you go low you need to eat sugar, which most of the time leads to an over compensation leading to having to take insulin to bring blood sugars back down. Protein only raises blood sugar a little, but works just as quick as sugar.

Over the last three weeks I dropped the 35% cream in my coffee/espresso and one or two BPC’s/day during my fasting window and saw dramatic results. I reduced average blood sugars from 6.5 to 4.5 and insulin use from 20 units long/day, 2-6 rapid/day to 10 long, no rapid per day. Also broke a three month weight stall and dropped 7lbs over this period.

So lower over all blood sugars, but also they are lower when I wake up and I do not see a rise in the morning like I used to. More stable during the day, although I did have lows, in the late afternoon initially and had to continue to drop insulin the following day until I was down to 6 long. I then adjusted back to 10 long/day to keep average blood sugar 4.5-5. Currently seeing if dropping coffee (just water) during my fasting window will make a difference.

Also my cpep when I was diagnosed was 340 and when I had it retested three months ago it was 373. Not sure if the IF/OMAD has boosted stem cell production to help rebuild pancreas or not, but better then going down. I was told when I was first diagnosed I could expect my remaining beta cells to die off. There is a company Viacyte that has had good success with implanting stem cells in T1’s to rebuild their pancreas beta cells. Since my wife refused to move to Edmonton, I looked up how to boost stem cells and came across fasting.

You may want to check out the work of Csaba Toth out of Hungary. He has had good results implementing a Paleolithic Keto Diet for T1 diabetics among other diseases and aliments.

For any T1 or even T2 diabetics who want to know more about how to implement these methods check out these two FB pages; One Meal A Day IF Lifestyle – Gin Stephens and Principia Carnivora. There are many others in the sphere of keto/lchf and fasting, but most do not allow for open discussions and are kinda cult like.

Good luck to everyone living with diabetes and trying to get it under control.

Chris Divito

Love the blog just wanted to mention that I have read and listened to a Dr Jason Fong who has done major research on diabeties and some great information.

Jason is great! https://intensivedietarymanagement.com/lchf-for-type-1-diabetes/

Am learning so much from this great blog. Thank you. I am wondering though if you can elaborate on the intermittent fasting. Like when and how you start – when you stop for the day, what is best to eat and then when to start the fast all over again. I am a type 2 diabetes on the verge of going onto 8ml insulin. I so much want to reverse this. Suppose this is nutrition only. Then One must still get to the exercise. Thanks RG

So glad your are enjoying the blog.

There are a ton of great resources on fasting coming out lately.

I know for me IF seemed to help me break through to help restore my insulin sensitivity where diet alone wasn’t getting there.

Ted Naiman has a good overview of the various approaches at http://www.burnfatnotsugar.com/IF.pdf

Jason Fung’s blog – http://www.burnfatnotsugar.com/IF.pdf – or videos are great – https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=FcLoaVNQ3rc

And Bob Briggs has a great way of making complex things understandable – https://m.youtube.com/user/butterbobbriggs

Make sure you track your blood sugars to know where your you’re at. Many can restore insulin sensitivity so that the need for insulin can be greatly reduced or eliminated.

Best of luck on your journey.

There have also been some great discussions on fasting on the closed FB group at https://www.facebook.com/groups/optimisingnutrition/

Great article. Diabetics are given the worst dietary advice generally. You included some Steve Phinney in your article so maybe you could now do some comparisons using his science – low carb, moderate protein, high fat. See how you go with that? As a nurse I despair at the poor health of diabetics who are eating what doctors and dietitians are telling them to.

Thanks Jeanie.

Phinney’s lowish carb and moderate protein typically comes out on top in the nutritional analysis. I have a range of recipe profiles lined up to be published over the next few months, so watch this space.

This article describes the ranking system – https://optimisingnutrition.wordpress.com/2015/03/22/the-most-nutritious-diabetic-friendly-meals/

The current batch of recipes profiled can be found at https://optimisingnutrition.wordpress.com/category/recipes/

Great work, Marty!

I have two comments to the biology of insulin/glucagon response.

First, the incretin effect of foods is responsible for more than 50 % of insulin and some of glucagon secretion. These hormones (incretins) are produced in the digestive system in response to all foods, but in varying amount. Obviously, more to simple (to digest) carbs, less to protein and very little to fat. Although this effect is relatively new to endocrinology, by now there is a vast amount of literature accumulated out there.

Second, based on the good work of Dr. Unger’s lab (and others) it is now clear that insulin is not simply an antidote to glucagon. Insulin has three major roles in the body and three different physiological levels are needed to carry out these. The highest naturally occurs in the pancreas where it can block synthesis of glucagon by the alpha cells, then the second level inhibits (or reduces the effect of) glucagon in the liver and the third, lowest level takes action in the peripherals. Now, the medium level mentioned is still significantly higher than what T1 diabetics shoot themselves with and insufficient inhibition of glucagon results in too high levels of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis in the liver, exactly because these represent the main action of glucagon there.

There is a huge amount of research going into glucagon receptor blockers right now to develop a dual hormone approach for T1 (and as a bad side effect, also T2) diabetics which could much more closely resemble the natural working mechanism of these blood sugar or rather energy homeostasis regulators.

A recent paper on this:

http://www.nature.com/nrendo/journal/v11/n6/abs/nrendo.2015.51.html

Thanks for the detailed feedback.

I’ve watched Roger Ungers’ lecture three times and I’m still getting my head around it all. Certainly lots more to learn in this area.

Once I work out the simple take home message I hope to update this article.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VjQkqFSdDOc

Hi Marty. Thank you for this excellent and thought-provoking article! As a T1 myself I often find baffling things going on with my control and am sure much of the explanation lies within this and linked articles. There is so much still to discover – its a fascinating field of research and study with potential benefits for so many. Please keep up the good work. Regards Ian

Cheers Ian. I’ve learned so much from people generously sharing their knowledge lately. I also see a lot of questions out there that need further investigation and answering. It’s fun to be part of the conversation. Diabetics need and deserve clear advice that works!

Dear Marty:

Thank you for writing this! I liked the data showing the effects of various foods. Also I liked the fact that you distinguished between diabetics and non-diabetics.

I’m one of the two co-authors of a blog post that you cited “” http://www.ketotic.org/2013/01/protein-gluconeogenesis-and-blood-sugar.html , which is citation [12] in your post above. (Disclaimer: I’m not the co-author most responsible for the scientific content.)

I have two comments.

My first comment is that you said “The observation that glucose does not rise significantly in response to protein is often taken to mean that protein is a non-issue. [11] [12]”, but in http://www.ketotic.org/2013/01/protein-gluconeogenesis-and-blood-sugar.html we were *not* saying that it is a non-issue “” we were saying only that it doesn’t increase blood glucose levels in non-diabetic people on a glycolytic diet, and that it doesn’t increase blood glucose levels *too much* in non-diabetic people on a ketogenic diet.

Please see also our follow-on post “” http://www.ketotic.org/2013/02/protein-ketogenesis-and-glucose.html “” in which we explicitly describe reasons why it *might* still be an issue, especially for ketogenic dieters, although we were unable to find conclusive evidence one way or the other about whether it *is* an issue.

My second comment is that your recommendation for people to get as little as 0.8g/kg seems likely to put them at risk of harmful effects! Please see http://www.ketotic.org/2014/01/how-much-protein-is-enough.html for our review of the evidence about safe levels, about those harmful effects of low-protein, and our bottom-line estimate that 1.4g/kg (of ideal body weight) for males and 1.2g/kg for females is the lowest safe amount.

I previously had some discussions with Amber in the comments on your previous post – http://www.ketotic.org/2012/08/if-you-eat-excess-protein-does-it-turn.html

When I was having discussions with people on various groups trying to work through what I saw in the insulin index data and what I saw in type 1 diabetics I kept getting pointed back to the two articles referenced.

I don’t think it’s what you intended, but taken to its logical extension people were inferring that protein was a magical macronutrient that disappeared if it didn’t contribute to you gainz. That’s why I went down the rabbit hole in this article to try to stick a few more pieces together to progress the discussion. I think we’re all just trying to deal with the data we see.

I definitely agree with your comment that 0.8g/kg is by no means ideal. It’s just noted as a minimum for maintenance and the bottom end extreme of Phinney’s WFKD triangle. I’m pretty sure Phinney is not recommending minimum protein for people either.

My main thesis in all of this is that optimal nutrition revolves around maximising nutrition in terms of aminos and vitamins while working within your personal glucose tolerance (i.e. your own pancreas’ ability to keep up with the glucogenic inputs). See https://optimisingnutrition.wordpress.com/2015/06/04/the-goldilocks-glucose-zone/.

I’ve added an extra paragraph in this article – https://optimisingnutrition.wordpress.com/2015/06/22/why-we-get-fat-and-what-to-do-about-it-v2/ – to try to clarify this. I will re-read this article and see if I can do a similar thing to elucidate this point.

Thanks for taking the time to write. I hope we can continue the conversation. It’s exciting what we can all learn from each other in this online world!

Zooko

Your comments got me thinking about how I could look at what it meant to balance insulin load versus nutrition quantitatively and what this would tell us about the optimal levels of protein for different people.

Have a look at this draft article… https://www.dropbox.com/s/w3khxpm09ztq0l6/how%20much%20protein%20how%20much%20carb.docx?dl=0

It certainly supports the case for maximising protein and moderating carbs for people without insulin resistance to maximise nutrition. This with what I think was your main point in your post and Bill Lagakos were trying to communicate. That is, for healthy people who do not have insulin resistance protein does not equal carbohydrates.

For people who do have insulin resistance or are aiming for theraputic ketosis it seems prudent to limit moderate or limit protein to avoid the insulinogenic effects.

Cheers

Marty

I was wondering what is your take on people who have Adrenal insufficiency, and who deal with hypoglycemia and reactive hypoglycemia. I was very luck to see great endo, and now I am supplementing with hydrocortisone. (replacement dosage) . that of course made me more insulin resistant, at the same time my body over produces insulin in response to food…(especially carbs) Low carb diet and IF really helps, but if I don’t include some carbs in every meal -my BS drops… some days really really low…

is that because I don’t have enough glycogen in my liver – or because my body can’t make enough? or?

i..e

normal BS sugar before the meal, normal fasting insulin;

2 soft side up eggs, on 1 tbs of butter, + 1 slice of bacon… 2 hrs later BS 35…

but if I don’t eat anything – my BS fluctuate very little. (as long as I use my HC as needed)

for now – veggies or nuts are my “to go” fix…

Hi Hala

Adrenal insufficiency is not really my area of expertise. My 2c would be to normalise blood sugars, maximise nutrition, find a way to relax / meditate and get outside a and move a bit and see the sun.

Beyond that I would suggest you check out people like Chris Kresser (http://chriskresser.com/the-modern-lifestyle-a-recipe-for-adrenal-fatigue/), Chris Kelly (http://www.nourishbalancethrive.com/, http://www.phoenixhelix.com/2015/03/28/episode-15-adrenal-fatigue/) and Robb Wolf (http://robbwolf.com/2012/04/09/real-deal-adrenal-fatigue/) who know a lot more about that sort of thing than me.

Best of luck on the journey.

Marty

Hello All:

I would love your help. Five years ago, a doctor gave me oral bioidentical progesterone. She said it would go through the second pass of the liver and give me wonderful sleep. Yes, it did for a while, but it produced a problem which I am still battling today even though I went off the medication after a few weeks. I think the medication harmed my liver.

I must eat every 3 hours now, even at night. This is because I cannot sustain my blood sugar longer than 3 hours. It drops to 80 and rarely lower, but when it does drop, I feel shakey, very weak. I keep going by eating every three hours some protein and some carbs.

Questions:

1. What is going on do you think ?

2. I have been to 5 endocrinologist and they are clueless. But one told me that I was having problems with my glycogen stores. Do you think there is something to this ? She wanted to increase my carbs significantly (not a good idea for someone with A1C of 6.1 and rising) and take steroids (not good idea for someone who is hyper-reactive/sensitive to foods, supplements, meds. ).

3. If the problem is glucagon storage, what can I do to help myself ?

Help !! Your input would be appreciated.

Susan

The info is rather intriguing.|

Love the site- very user pleasant and lots to see!|

A few corrections: excess protein consumption is either converted to energy through the Krebs Cycle or else converted to fat and stored.

Insulin and glucagon are hormones secreted by the pancreas in a feedback loop based on blood sugar levels only. Receptors detect high blood sugar and secrete insulin. Receptors detect low blood sugar and secrete glucagon. They can exist in the blood at the same time (residual amounts) but are not secreted at the same time (e.g. During fasting glucagon is secreted to mobilize fat stores and break down amino acids for energy, then you eat a high sugar meal and blood glucose levels spike causing insulin secretion).

Very educational article! I am currently insulin resistant and have issues with visceral fat. I am doing a modified ketogenic/paleo diet and am actively losing weight. My question is: does fiber reduce the insulin/glucose response for protein the way it does for carbohydrates? Is there such a thing as “Net Protein”?

Great in depth information here!!

I eat a lot of protein especially when going keto. Always wondered how all that protein was affecting my insulin response and blood glucose levels.

Can’t say enough about how interesting and informative this article was!

Great job!

Thanks Mike!

Thanks for the article Marty… As a T2D (not yet on ketosis but have lowered the carbo to 50-80 grams range while meeting Protein requirements of 80 grams) it makes me wonder if it is better to spread the Protein intake to 4 times a day while having all the carbos for nutrition (mostly low GI ones) by lunch time ,,a modification of more than three meals of smaller proportion of SAD diet which Doctors used to recommend

Not sure. My only thought is that you might do better to eat whole foods that don’t come in neat separate macro packages. A compressed eating window can also have a ton of benefits.

By way of background my 3rd health failure at xmas 2015 had me in ‘adrenal failure’ & gut disbiosis for most of 2016, reflecting my life long problems of G6PD deficiency confirmed in March 2017. Your article piqued my interest because of a recent health challenge.

I am Zero Carb for obvious reasons & follow a Magnesium protocol to reduce the iron overload of Haemolysis. Mineral imbalance an oversite in the above article.

HIIT & fasting is detrimental for my condition, but I do have to deplete my glycogen stores before I break fast for a 4hr eating window 2 – 6 pm, finding by my reading, that 12 hrs plus is sufficient for autophagy. I then intentionally overeat [increased fat] to gain weight & support an increasing physical life. Although I did find I was essentially substituting a breakfast with specific protein powders & Coconut Oil & am trending toward 2 meals at noon & 6pm.

Without the conflictions of carbs or fibre, starting with a reintroduction of minimal low caffeine [adrenal/cortisol] I had a rise in FBG from low 4s to high 5s that continued with experimentation of low histamine cooked meats creating a Glutamate overload, I believe, readily converted to glucose. These affects are easily seen in a return of red coloured cloudy urine. Over the month I returned to raw meat & boosted antioxidant support for a clearing of red [Lipofuscin pigment granules] but continued high BG & cloudy sludge.

With past edema experience of low Potassium [K] I increased K for a return to clear cloudless urine & relief of Chronic Fatigue & perhaps [postprandial BG 4.8] return of better FBG just happening now. I doubt a HbA1c would be better than 5.4 of previous 5.8

Also intriguing is recent, retrying, use of pre meal ACV for avoidance of postprandial narcolepsy.

I believe in & hope for a return of LC dietary fibre when my iron is reduced.

Anyone can read my experience in https://www.my-diary.org/users/894906 ‘Canary in a Coal Mine’.

his is amazing information. This is helpful for me na nahihirapan sa pagtulog at nalilito sa kung anong vitamins ang i-take para maging healthy. But yes, having a healthy lifestyle is still the best answer.

The article is great and useful, providing enough information for users or those looking for information. I like it very much. Thank you very much.

thanks heaps!