Are your blood sugar levels and weight loss goals not aligning despite your best efforts?

It might be time to peek into the stress-cortisol-blood sugar triangle. This article unravels the complex interplay between stress, cortisol, and blood sugar, shedding light on how they can make or break your weight loss journey.

Discover the science-backed explanations for those stubborn scales and learn proactive strategies to manage stress, balance your blood sugar, and reignite your weight loss progress.

Your journey towards a healthier weight amid life’s stresses begins here.

- What Is Stress?

- Is Stress Bad?

- Drain Your Stress Bucket

- How Does Stress Affect My Body?

- What Are the Different Types of Stress?

- Stress and The Adrenal Glands

- Cortisol and Other Body Systems

- The Daily Ebb and Flow of Cortisol

- How Does Cortisol Affect My Weight Loss Journey?

- How Does Cortisol Affect My Blood Sugar?

- How Does Cortisol Affect My Body Weight?

- Stress and Blood Glucose Balance

- How Can I Avoid Adrenal Problems?

- How Can I Fix My Adrenal Issues?

- Summary

- More

What Is Stress?

Simply put, stress refers to, ‘any type of stimulation that causes physical or psychological strain.’

Is Stress Bad?

Stress isn’t all bad.

Some stress is good for you; it allows you to grow and improve!

Distress is stress that harms us, while eustress motivates us to make a positive change, adapt and grow.

If you’re trying to improve your skills, training with someone a little better than you will improve your skills.

Resistance training is a hermetic stressor that allows you to improve by applying additional stress to your body.

But in all things, the key is to stretch yourself just enough to grow consistently but not so much you break.

Too much stress can be detrimental. Even progressive overload without adequate rest can soon lead to fatigue, burn out and injury. While it might seem easy initially, you can find yourself putting too much weight on the bar before long.

As with most things, if a little bit of something is good, more may not be better—especially when it exceeds your capacity to recover.

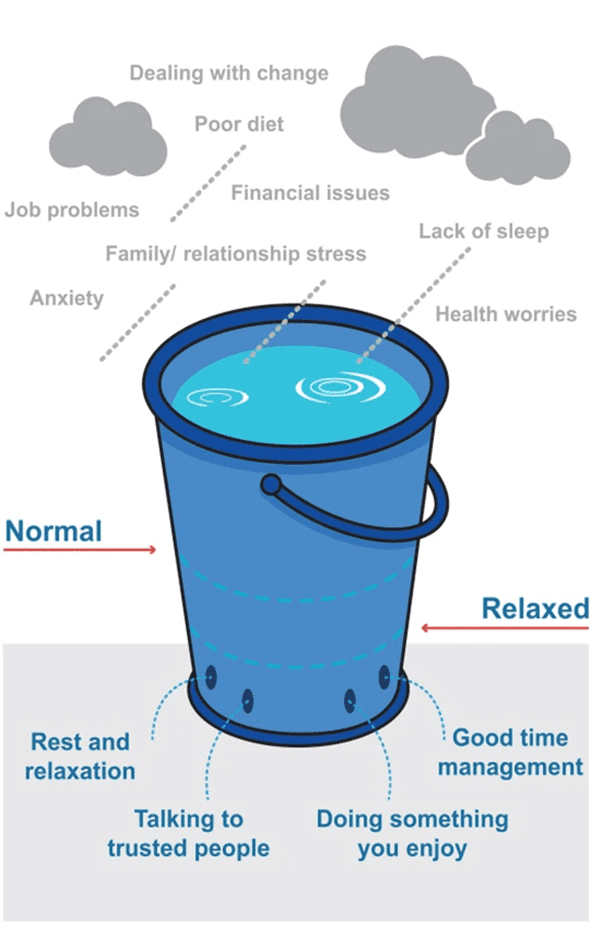

Drain Your Stress Bucket

In our Macros Masterclass, everyone is excited in the first week, ready to make massive overnight progress. So, before things become more challenging, we encourage them to evaluate and empty their stress bucket a little.

Anything new can be stressful to adapt to, and the later phases of weight loss can become a stressor on your body. However, it’s often the cumulative stress from your life that often breaks you.

Before you start something important that you want to succeed at, it’s best to start by managing some of the significant stressors plaguing your life. That way, you’re less likely to throw in the towel if things get harder later.

In the rest of this article, we’ll look under the hood to understand what’s happening in your body and how you can proactively manage your stress so it doesn’t break you in the long term.

Ready to dive in?

Let’s go!

How Does Stress Affect My Body?

There are a ton of physiological reactions that occur when your body is stressed. Too much stress for prolonged periods can tax the body.

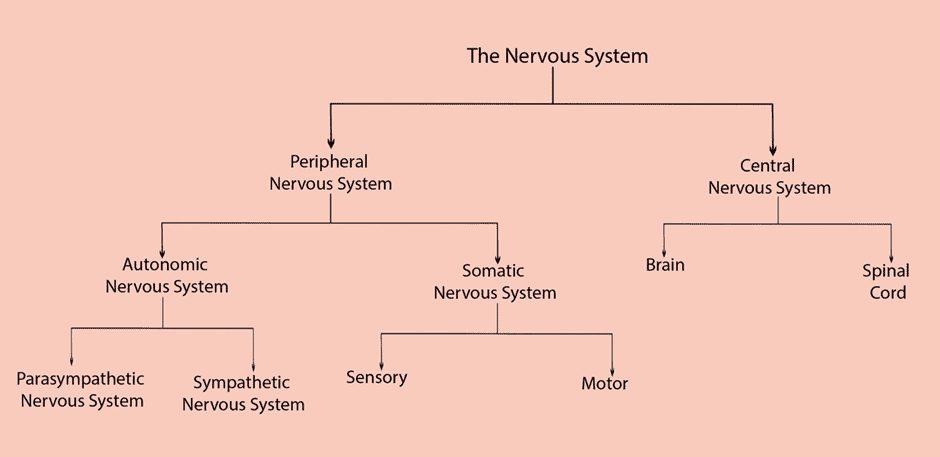

Your nervous system is divided into two sections based on function: the autonomic nervous system and the somatic nervous system.

- Your autonomic nervous system regulates automatic functions like heart rate, breath rate, and blood pressure.

- In contrast, your somatic nervous system controls your voluntary movements.

Your autonomic system is broken up even further between the sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous systems (PNS). They are commonly referred to as your ‘fight-or-flight’ and ‘rest-and-digest’ states.

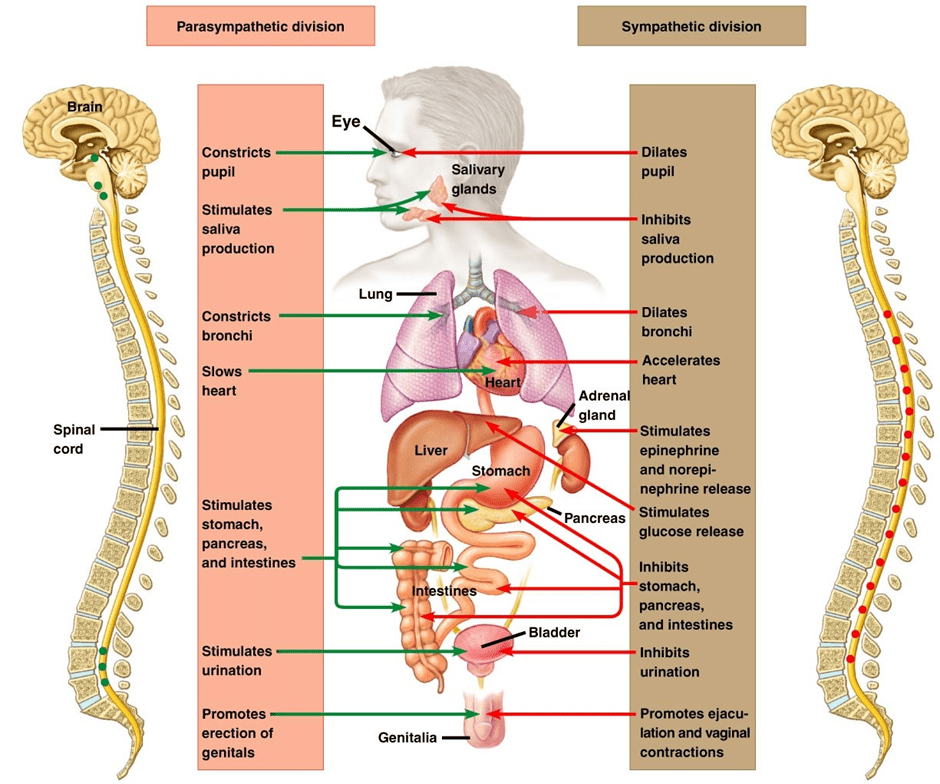

The Parasympathetic Nervous System

When you’re in a parasympathetic state, your heart rate, blood pressure, and breath rate are regulated, and you’re relatively relaxed. When we’re in ‘rest-and-digest’, our perceived stress levels are low. We can digest and absorb food, move our bowels, reproduce and have a libido, grow and regenerate, and our immune system can function adequately.

It’s estimated that we are in this state around 80% of the time.

The Sympathetic Nervous System

When you are in a sympathetic state, your pulse, blood pressure, and breathing rate all increase to move more oxygen throughout your body, digestion, healing, and immune function halt to prioritise your limited resources to get you out of immediate danger, stress hormones like noradrenaline and cortisol are released.

For more on digestion, check out Digestion: The Missing Link Between Your Nutrient-Dense Diet and Optimal Health.

During evolutionary times, the fight-or-flight response would be activated to get us out of danger, like if we were trying to outrun a predator or pulling ourselves over a rock face after nearly falling over a cliff.

Our bodies would respond by releasing stress hormones like norepinephrine and epinephrine. It is estimated that we only evolved to spend around 20% of our lives in a fight-or-flight state.

The release of this hormone duo would work quickly to potentially save your life; by supporting vasoconstriction, they would force expedited blood flow and oxygen to your brain and muscles so you could think and move faster.

Additionally, they would help you convert stored energy in the form of liver glycogen into glucose in your bloodstream to fuel your metabolic needs. Digestion and immune function halt abruptly so your body can save energy to keep you alive in what it perceives as a life-or-death situation.

As the stress continues and becomes more chronic (i.e., long-lasting), the body signals to the brain that this ‘danger’ persists. Your amygdala—or your ‘lizard brain’ that’s responsible for fear—sends a signal to your hypothalamus. Next, your hypothalamus sends a signal that eventually gets transmitted to the adrenals, telling them to release the infamous stress hormone cortisol.

What Are the Different Types of Stress?

When someone mentions stress, most people think of its psychological and mental aspects. While these stressors substantially contribute to your overall stress burden—especially in this day in age—other types do, too.

Physical Stress

We could define physical stress as excessive physical activity from intentional exercise or hard labour.

While you may voluntarily work out at the gym daily, your body might not understand that! Physical activity—whether it’s having to walk 100s of miles as you hunt for food or running by choice for fun—is a stressor. This is why it’s essential to take rest days and alter your training schedule if you’re getting weaker, your sleep is suffering, or you’re showing signs of burnout.

When you exercise, you’re intentionally damaging your muscles, so they grow bigger and stronger. Counterintuitively, this can lead to increased inflammation and water retention while your body recovers. Hence, you may see a bump on the scale on days you worked out harder than usual. Exercise will also increase your appetite to ensure you get the necessary nutrients and energy to recover. Neither of these ‘fun facts’ is really a problem, so long as you’re also getting adequate rest and avoiding excessive fatigue that can stall your progress.

Physical stress could also result from inadequate physical activity.

Insufficient physical activity also stresses the body. Humans thrive on movement; we are an extremely mobile species!

If we’re not moving, our muscles aren’t getting any stimulation, the circulatory and lymphatic systems do not move adequately, our gastrointestinal organs are restricted, and our posture takes a hit. We’re also not using as much energy, so we’re more prone to energy toxicity if we don’t change how much we eat!

Physical stress can stem from a lack of sleep.

Sleep is critical for recovery. Changes in your sleep are also a huge red flag that something in your life needs attention.

Physical stress can result from poor blood sugar control.

While stress can cause poor glucose control, erratic blood sugar is also a stressor. As you can tell from the sounds of it, this can turn into a vicious cycle! When our blood sugar rises and plummets not long after, this ‘lowest of the low’ can cause them to fall into an uncontrolled binge on less-optimal foods. This is very common in people with Type-2 Diabetes. For more details on how to get off the blood sugar rollercoaster, check out our article on reactive hypoglycemia.

If your cortisol levels are also off the charts, this can create an environment for insulin resistance, sex hormone imbalance, and reduced thyroid output. The perfect trifecta for weight gain!

Physical stress from a chronic illness.

Whether you’re suffering from a specific disorder like autoimmunity, cancer, diabetes, neurodegeneration, or another condition that propagates chronic inflammation, this can engage the body’s stress response. Other examples of illnesses that can activate the fight-or-flight response include (but aren’t limited to) chronic gut dysfunction, Lyme coinfections, and other long-term infections.

Biochemical Stress

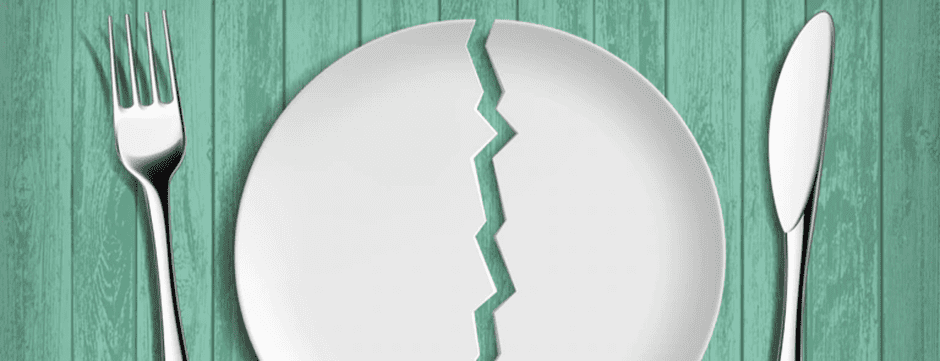

Nutrient deficiency and (or) excessive energy deficit can propagate biochemical stress.

This can include eating a nutrient-poor diet, a diet with insufficient calories (i.e., chronic dieting), not eating enough (infrequent meals and skipping meals), chronic fasting, and too few carbs when your body is already stressed.

In our Macros Masterclass, Micros Masterclass, and Data-Driven Fasting challenges, we guide our Optimisers through 4-week periods of dialling in their macros, nutrient density, and blood glucose, followed by a maintenance period.

Before you start pushing again, the recovery phase allows your body time to recover. It also allows you to practice healthy maintenance, which is often more challenging than the weight loss period itself. If you engage in back-to-back-to-back-to-back challenges or continue to keep your calories low 24/7-365 in the hopes of losing more and more and more weight, your body will eventually perceive starvation. Over time, the effects of high cortisol, which you will read about below, can occur, causing you to have dysregulated blood sugar, lower muscle mass, and unfavourable body weight.

Chronic fasting is no different than what we mentioned above. Many of our Optimisers come to Data-Driven Fasting after burning out and stalling with extended fasting approaches. Unfortunately, these approaches often lead to losing precious lean muscle mass without adequate protein and nutrients. When your body loses precious lean mass, cortisol rises as your body perceives starvation.

In the short term, things might be ok. But your stress hormones and appetite will increase as you go for more extended periods without adequate protein and nutrients.

Very low-carb diets can also cause biochemical stress.

Lastly, while many do very well on an uber-low-carb diet, others don’t over the long term. More often than not, this pertains to women. I wanted to take a minute to explain what may be going on.

A low-carb diet keeps blood glucose relatively low and stable. However, for some people who tend towards the hypoglycaemic (low blood sugar) side, this might be unfavourable as blood sugar will fall too low, triggering a cortisol response. This can further exacerbate thyroid and sex hormone dysfunction. Once again, lower-carb diets are great for most people wanting to lose weight, but not if there is pre-existing adrenal fatigue or imbalance!

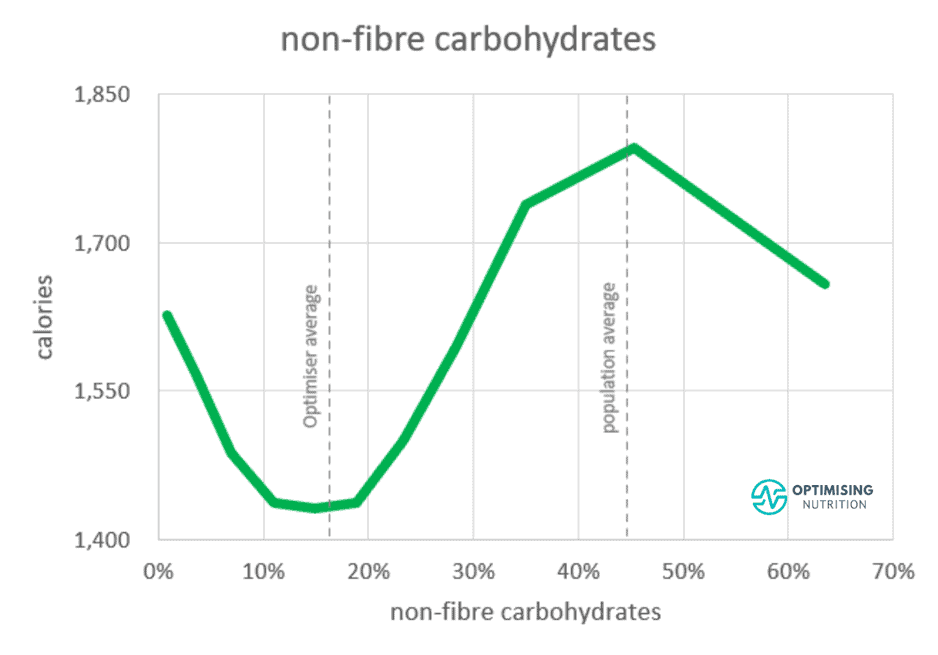

As shown in the chart below from our satiety analysis, we see a 25% reduction in calorie intake when we move from the hyper-palatable fat-and-carb zone to a lower-carb diet with 10-20% carbs. However, pushing lower isn’t necessarily better.

Because we have an appetite for some carbohydrates, pushing our carb intake below 10% of total calories seems to align with eating more. Although we can create glucose from protein via gluconeogenesis, it’s harder and more stressful for your body to do.

If you have a tendency towards low blood sugar or live a higher-stress life because of a chronic illness (i.e., autoimmunity), you struggle to eat enough calories, you are more physically active in your job or from workouts, you already partake in fasting, or you already have some degree of adrenal fatigue, it’s essential to consider how much carbohydrates may benefit you.

While it’s ideal to dial your carbs back if you’re experiencing large blood sugar swings, reducing carbs even further to achieve flatline blood glucose isn’t necessary or optimal. If your rise in blood glucose after meals is less than 30 mg/dL (1.6 mmol/L) to lose weight, you’ll likely benefit from dialling back the fat in your diet rather than pushing carbs lower.

Nutrient and (or) calorie excess creates biochemical stress.

Eating excess energy can stress the body into obvious symptoms like fat gain, hyperglycemia, high blood pressure, and high blood lipids. Unsurprisingly, it is stressful for the body’s organs to carry extra weight, especially the heart and skeletal system. High blood sugar also causes oxidative damage to various body parts like the eyes, nerves, and blood vessels.

Nutrient excess also includes over-supplementation. Your body has to work harder to clear the nutrients it doesn’t need, which can create problems for the body. Nutrients like copper, iodine, and vitamin A can even cause toxicity. Additionally, overconsuming other nutrients in relation to synergists and antagonists can create an imbalance that causes stress to the body.

For more info, see:

- Nutrient Balance Ratios: Do They Matter and How Can I Manage Them? and

- Nutrients: Could You Be Getting Too Much of a Good Thing (from Supplements and Fortification)?

Environmental Stress

Your environment around you constantly interacts with your immune system. Once alerted, your immune system can activate numerous inflammatory mediators along with your fight-or-flight response.

As it turns from acute to chronic, this increases and takes a toll on your adrenals (amongst other things). Some examples of environmental stressors include mould exposure, pollution (air and water), and direct toxin exposure.

Biomechanical Stress

Pain from injury, trauma or surgery can stimulate the fight-or-flight response. No matter if it’s chronic or acute, both can keep the body in a stressed state.

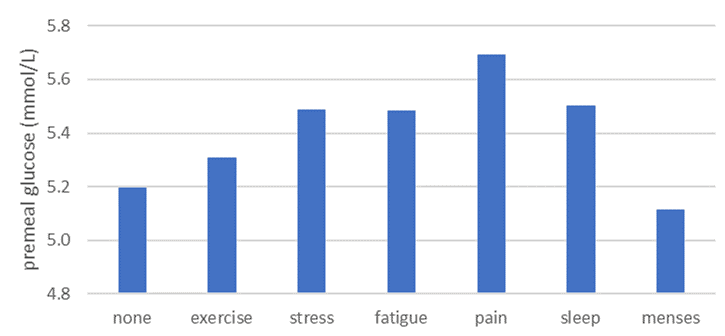

In the DDF app, users can flag various ‘events’ affecting their blood glucose. As you can see in the chart below, people experiencing pain tend to have the highest blood glucose levels, followed by poor sleep, stress, fatigue and after exercise.

Mental and Emotional Stress

When we typically think of stress, we usually think about mental and emotional stress. Some common contributors are death of a loved one, grief, relationship problems (with friends, family, and colleagues), career challenges, school stress, and financial hardships. However, just about anything can cause mental and emotional stress.

Stress and The Adrenal Glands

Chronic stress lands us in a long-term state of fight-or-flight. If you remember from above, we only evolved to be here for around 20% of our lives.

So, what are the implications in our modern world?

Whether it be from being chased by a predator, not having enough money for your mortgage payment, or too many competing deadlines at work, the body’s reaction is the same when it perceives stress.

Initially, the body will release fast-acting stress hormones like epinephrine and norepinephrine. As the stress turns from short-term to long-term, it will begin releasing cortisol.

Cortisol is a hormone produced by the adrenals, which are two small glands that sit atop your kidneys (pictured below). Aside from cortisol production, they create sex hormones like estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. They also produce other hormones that play a role in fluid and electrolyte balance.

As the adrenals perceive stress for longer and longer periods, they become increasingly tired and struggle to keep up with the output that is required of them. Over time, they may slip from a hyper-productive state where they overproduce cortisol to compensate into a state where they cannot make enough cortisol to keep up with demand.

Symptoms of adrenal fatigue include:

- stubborn belly fat gain;

- trouble getting out of bed without your morning coffee;

- feeling ‘tired but wired’ or feeling exhausted but unable to sleep when your head hits the pillow;

- being a ‘night owl’;

- poor sleep, frequent waking, and insomnia;

- loss of weight or muscle tone;

- inability to handle stress;

- edginess;

- sweaty palms;

- clenching or grinding teeth;

- high blood pressure and high resting pulse;

- imbalanced sex hormones;

- the need for caffeine to accomplish anything, and

- an irregular cortisol curve.

Symptoms of hypoadrenia include:

- weight gain around the hips, belly, and waistline or unexplained weight loss;

- low energy;

- fatigue;

- brain fog;

- poor immunity and frequent illness;

- wounds slow to heal;

- variations in thyroid output;

- imbalanced sex hormones;

- poor digestion, constipation, and diarrhea;

- orthostatic hypotension;

- postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS);

- low mineral levels, especially sodium and potassium;

- loss of muscle tone;

- a need to wear sunglasses;

- low blood pressure and a slowed pulse;

- poor blood glucose control;

- episodes of reactive hypoglycaemia and

- hunger fluctuations (no appetite to binge eating).

Cortisol and Other Body Systems

So, your cortisol is high.

This is just an adrenal problem.

Right?

Actually, no.

As we’ve started to look more into how different organ systems influence one another, we’ve actually learned that chronically high cortisol output can have detrimental effects on many other parts of the body. We’ve mentioned a few below that are somewhat relevant to metabolic health and metabolism.

Insulin Resistance

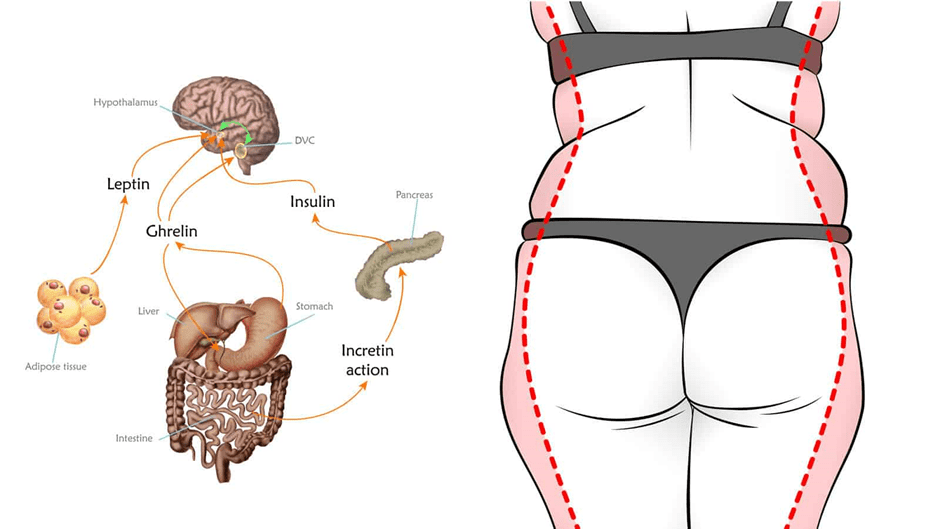

During stress, cortisol triggers the release of glucagon, which opposes the effects of insulin. Thus, high-stress levels can actually raise blood sugar and create insulin resistance. This is why stubborn body fat is known as the ‘stress belly’.

For more on insulin resistance, check out:

- The Real Reason Why You’re Insulin Resistant and the Macros to Reverse It,and

- What Is Insulin Resistance (and How to Reverse It)?

Sex Hormone Imbalance

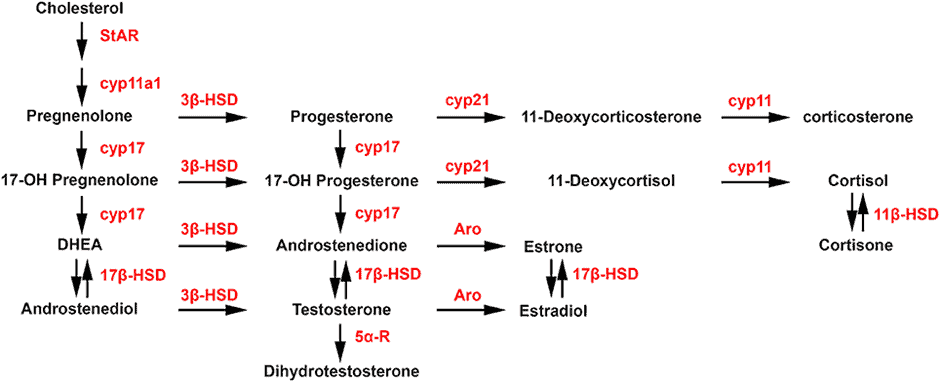

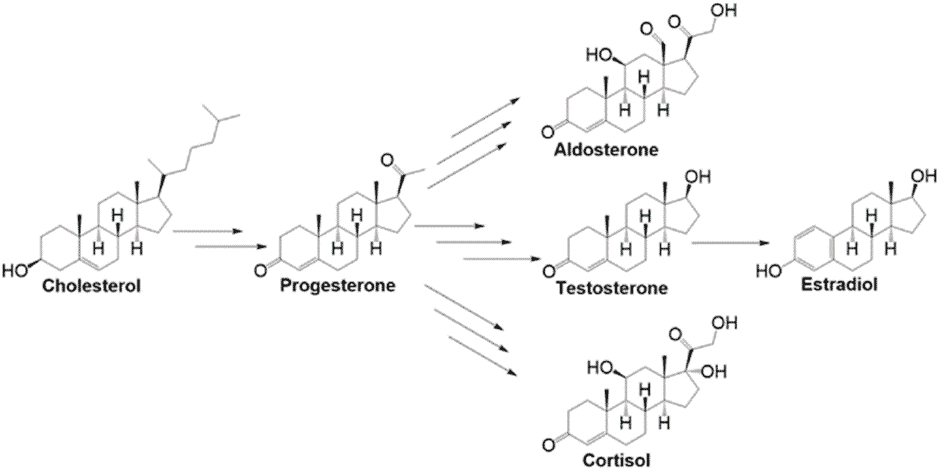

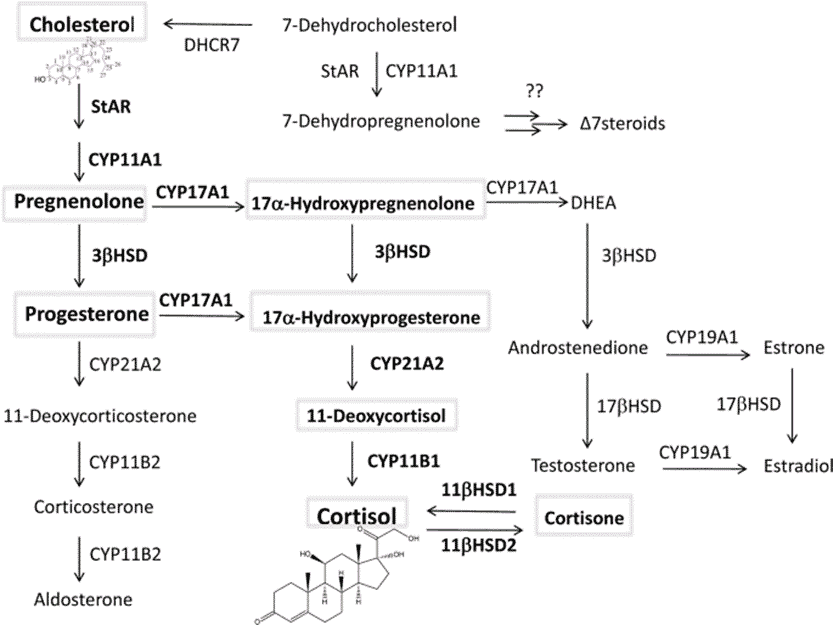

Like sex hormones (i.e., estrogen, testosterone, and progesterone), cortisol is a sterol hormone. Interestingly, they are all synthesised down the same pathway. Your body is efficient, so it isn’t surprising that it prioritises the production of the hormone that will keep you alive (i.e., cortisol) in times of stress.

Subsequently, the production of certain hormones—like progesterone—is halted so the body can optimise its cortisol production. This can contribute to imbalances in other sex hormones, like estrogen and testosterone.

Additionally, sex hormone imbalances can be exacerbated by erratic blood sugar, too.

Insulin is also a hormone, and it requires something known as sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) to be eliminated. By producing more and more insulin, the body has less SHBG left to metabolise hormones.

Interestingly, new research is starting to show that conditions like amenorrhea, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, menstrual cycle irregularities, and other disorders related to the reproductive system may be rooted in chronic stress, adrenal imbalance, high cortisol, and blood sugar dysregulation.

For more on eating to support your hormones as a female, check out Blood Sugar, Insulin, and What to Eat During Each Phase of Your Menstrual Cycle.

Thyroid Imbalance

The body’s endocrine system refers to the glands that produce hormones and the hormones themselves. Hormones are messengers that tell different body parts to do different things depending on the environment. Endocrine organs include the thyroid, pancreas, hypothalamus, pituitary, adrenals, thymus, pineal gland, parathyroid gland, and reproductive organs (i.e., testes in males and ovaries in females).

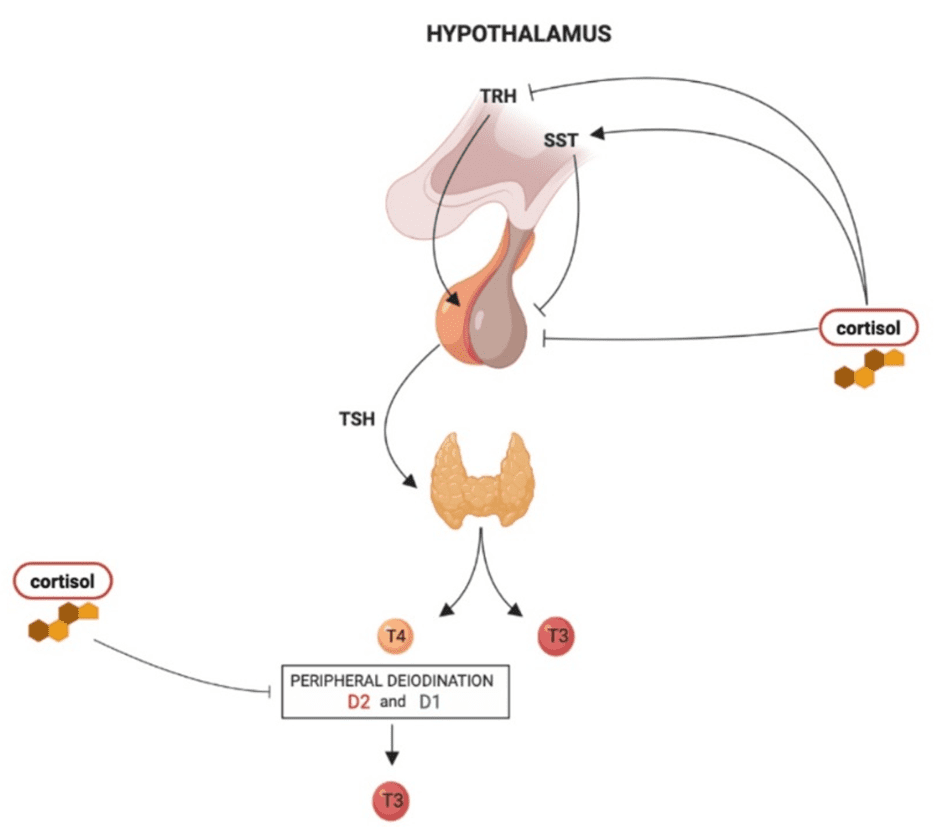

The hypothalamus and pituitary are the ‘control centres’ of the rest of the body. Thus, the pituitary and hypothalamus tightly regulate the adrenals, and the state of the adrenals greatly influences the pituitary and hypothalamus. Therefore, when the adrenals are under stress, the pituitary and the hypothalamus can also take a hit and affect the function of other organs. Cool but complicated, isn’t it?

Anyway, the hypothalamus and pituitary also stimulate thyroid function through a hormone known as thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). TSH stimulates the production of active thyroid hormones like T4 and T3. When the pituitary and hypothalamus are stressed, sometimes TSH isn’t produced adequately. Thus, we can see irregular thyroid output (hypo or hyper). The same goes for follicular stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteal hormone (LH) in a woman’s reproductive system.

Fluid and Mineral Imbalances

As we mentioned, the adrenals produce other hormones—known as mineralocorticoids—that help the body regulate fluid and mineral balance.

These hormones include aldosterone, a hormone that regulates blood pressure by managing sodium and potassium levels, and antidiuretic hormone, which controls the amount of water your body excretes and reabsorbs.

As your adrenals become worn down due to long-term stress, the production and utilisation of these hormones are often dysregulated. As a result, we can see increased mineral excretion or retention and increased water loss or water retention.

Not only does this affect how much you pee, but it also influences your blood pressure, heart rate, and circulatory standings!

For an excellent electrolyte recipe to support your adrenals with the right balance of critical minerals, check out our optimal electrolyte mix.

Allergies and Increased Reactivity

There is growing evidence that low cortisol (i.e., hypoadrenia or lowered cortisol output from prolonged adrenal exhaustion) plays a role in hyperreactivity to environmental stimuli. In other words, it makes you more susceptible to reacting to the things around you, whether it be food, water, air, or something in them.

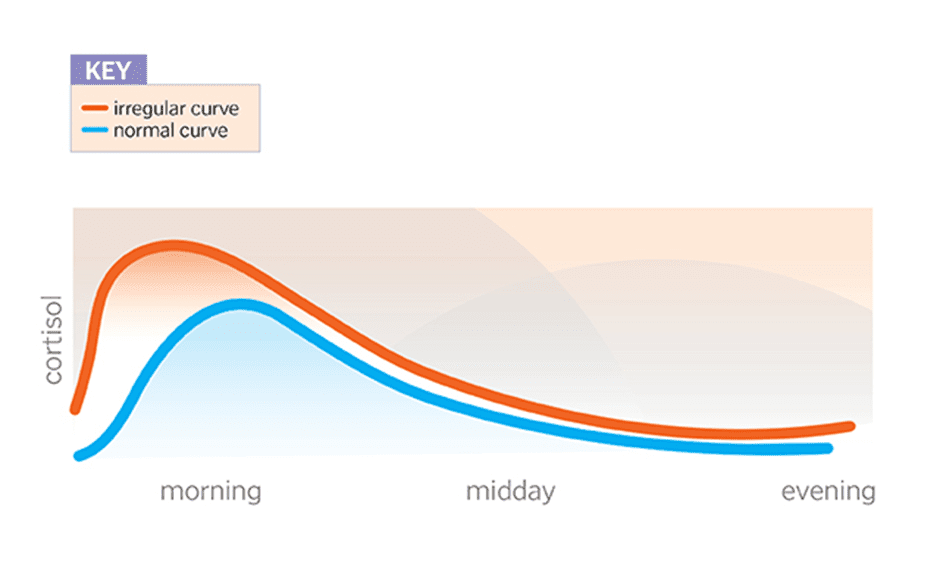

The Daily Ebb and Flow of Cortisol

Cortisol, like most hormones, runs on a clock or a timer we know as your circadian rhythm. This means it’s released at similar times throughout the day.

Cortisol reaches its peak when you get up, causing you to wake in the morning. As the day goes on, it slowly declines until you go to sleep; low cortisol makes you sleepy and able to ‘hit the pillow’. Around 1-3 a.m., it will reach its lowest point before it increases again, which will wake you up.

So, what does this have to do with stress and everyday life?

When you’re chronically stressed, this curve can be altered or shifted. Often, people

with weak adrenals do not see their morning cortisol spike much—if at all—and their overall cortisol levels are relatively low. This may make them feel stuck, or like they’re running on empty in the morning.

Someone might also produce too much cortisol, or their curve might shift towards the right (i.e., later in the day). These people see their cortisol peak later in the day or the evening, giving them the ‘talent’ of being night owls.

How Does Cortisol Affect My Weight Loss Journey?

Your body is a complex system of a slew of different parts known as organ systems. These systems relate to one another in more ways than we probably realise!

As we mentioned above, the adrenals are closely interrelated with the thyroid and reproductive systems; you can think of it like a pyramid with the adrenals at the base. When the adrenals start to take a beating, the thyroid and reproductive systems might also slide downhill.

As we mentioned earlier, cortisol and sex hormones like testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone are synthesised down the same pathway. Cortisol is essential for life; we need cortisol to keep us alive. While cortisol in excess can be a problem, we would die without it!

Subsequently, our bodies prioritise the production of cortisol in times of scarcity over sex hormones. As a result, we often produce less testosterone (our muscle-building and libido-forming hormone), progesterone (for women, this is usually the first thing to go when menstrual cycles become too short or too long), and estrogen.

However, the body tends to alter the synthesis of this hormone disproportionally, often still producing more estrogen relative to testosterone and progesterone. As a result, someone might experience high-estrogen or ‘estrogen-dominance’ symptoms.

As shown in the image below, your sex hormones are produced from cholesterol. When cortisol is chronically elevated, more testosterone is converted to estrogen (estradiol).

High estrogen in women looks like irregular and heavy menstrual cycles, weight gain around the hips, buttocks, and thighs, mood changes, and hot flashes. They can also end up with symptoms of low progesterone, like anovulatory cycles and cycles much longer than the 28-day average. In men, this can look like poor muscle tone, baldness, gynecomastia (i.e., man boobs), and weight gain.

How Does Cortisol Affect My Blood Sugar?

Insulin and cortisol also have a close relationship.

When stressed, your body releases stress hormones, as we’ve described. These hormones also signal the body to release glucagon—the antagonistic hormone of insulin—to break down stored glycogen and body fat so that we have the energy to fuel us through whatever stressful situation we face. It’s how we access our body’s energy stores.

This is fine now and then when we run into danger. But after consecutive releases of glycogen and energy stores from the body, energy stores begin to run thin unless someone eats accordingly. As a result, the body starts to release its muscles for fuel, which can harm your body’s metabolism over time.

As mentioned above, cortisol is synergistic with glucagon, the antagonistic hormone to insulin; hence, cortisol spikes tend to result in massive blood sugar drops. This is why we often reach for energy-dense, ultra-processed comfort foods when we’re stressed.

If you’re making poor choices when you’re stressed—which most of us do when we’re not eating intentionally—we might be setting ourselves up for a front seat on the blood sugar rollercoaster, or we exacerbate the one we’re already on.

We get stressed, our blood sugar plummets, and we binge on the first piece of edible hyper-palatable junk we can get our hands on. In turn, this spikes our blood glucose, crashing down shortly after, and it likely provides little protein or nutrients.

For more on how the blood sugar rollercoaster can affect you, see Reactive Hypoglycaemia: Symptoms, Causes & Dietary Solutions.

How Does Cortisol Affect My Body Weight?

The human body is primarily regulated by signalling molecules known as hormones. Hormones and the glands that produce them make up the endocrine system, which we mentioned briefly earlier.

The endocrine system includes the thyroid gland, pancreas, hypothalamus, pituitary, adrenals, and reproductive system (i.e., ovaries and testes, depending on sex).

Your thyroid gland is a butterfly-shaped gland on your neck that regulates your metabolic rate by producing hormones like triiodothyronine 3 and 4 (T3 and T4).

Sex hormones, including estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, regulate your reproductive system. In males, the dominant hormone is testosterone; in females, the dominant hormones are progesterone, estrogen, and to a lesser extent, testosterone. These hormones affect your ability to burn fat, retain muscle, and regulate metabolism.

The adrenal glands produce cortisol, a sterol hormone derived from cholesterol made from the same pathway as the sex hormones. So, despite cortisol being a negatively connotated ‘stress’ hormone, we need some cortisol to keep us alive. After all, it regulates our heart rate, breathing, and blood pressure.

Because of a phenomenon known as ‘cortisol steal’, our bodies prioritise the production of cortisol in times of need. Subsequently, it produces fewer sex hormones in favour of cortisol. As a result, our hormone production decreases, and our hormone levels become imbalanced. In the following picture, you can imagine all the production being shunted to the centre towards cortisol.

When it comes to the thyroid, we see a similar trend take place. Cortisol inhibits the conversion of T4—the less active thyroid hormone—to T3, the active form that stimulates your cells. As a result, cortisol increases TSH levels, which is a major symptom of hypothyroidism. Cortisol also can increase the rate at which reverse T3, the anti-thyroid hormone, is produced. High reverse T3 levels are often indicative of high cortisol levels.

So, what does this mean?

When the body produces lots of cortisol for an extended period, whether it be from stress at work, overexercising, too much fasting, over-dieting, nutrient deficiency, or chronic illness, your sex hormones and thyroid can take a hit. So, it’s possible to gain weight despite eating less, fasting, and working out too much!

Additionally, the excess activation of the adrenals tends to take a toll on the pituitary and the hypothalamus, two master-regulatory glands in the brain. These two structures are often referred to as the ‘control centres’ of the adrenals, reproductive system, and thyroid.

As the demand for cortisol continues, the adrenals go into overdrive. As time and time goes on, this begins to take its toll. As a result, the hypothalamus and pituitary suffer, too, as they produce hormones that regulate the other organ systems, like Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) of the thyroid, Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) and Luteinizing Hormone (LH) of the reproductive system, and Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACH) of the adrenals. You could liken the fall of the hypothalamus and pituitary to pulling a rug out from underneath a table full of food.

If you are hypothyroid or suffer from hormone imbalance, it’s critical to evaluate the state of your adrenals. Often, the problem’s origin partially comes from excess stress and long-term adrenal overuse!

Stress and Blood Glucose Balance

Stress can increase blood sugar, too. Your body is on high alert, with plenty of fuel in the bloodstream, ready for action.

In fact, high cortisol is known to cause insulin resistance; this is why one of the most characteristic features of longer-term adrenal imbalance is weight gain around the stomach (i.e., stubborn body fat).

How Can I Avoid Adrenal Problems?

This is plenty you can do to avoid adrenal imbalances that negatively affect your metabolism. Avoiding excessive fasting and incessant dieting is probably step number one!

You can still lose body fat and get (and stay) at the weight you want to be by learning to use your blood glucose as a fuel gauge, as we do in our Data-Driven Fasting Challenges. But the key is to give you just enough stress to see some change and then let it recover. Using your glucose as a fuel gauge to guide when and what to eat ensures you achieve a long-term energy deficit without overdoing it.

Additionally, you can try out our four-week Macros Masterclass to learn how to give your body what it needs when it needs to thrive without excess energy. We find that progressively dialling back extra energy from carbs and fats while prioritising protein and other nutrients provides much better long-term results than trying to limit your calories to some arbitrary number.

We also discuss how to practice maintenance and when it’s time to move into this phase. A healthy balance between push (dieting) and pull (maintenance) is critical for long-term, sustainable weight loss.

How Can I Fix My Adrenal Issues?

Depending on the state of adrenal fatigue you’re experiencing and what caused you to get into the hole in the first place (i.e., too much exercise, dieting, work stress, poor diet, or all of the above), it might take longer or shorter to get back to baseline. Essentially, your body needs to feel like it’s safe again. Below, we’ve included some essential tips to get you there.

1. Aim for three solid meals a day.

Infrequent eating times and long gaps between meals can leave you hypoglycaemic, exacerbating your adrenal issues. While we find that most people see the best weight loss results with two meals a day if you’re trying to recover, start eating three meals a day if you’re trying to get back to baseline without any intervention. This will give your body more-even fuelling throughout the day.

2. Avoid inflexible fasting schedules, excessive dieting, and skipping meals unnecessarily.

Data-Driven Fasting can help you learn how to use your blood sugar as a fuel gauge to determine when you need to eat and what can help. While we often use this for dieting, we can also use it to get out of dieting danger and verify when our blood sugar is too low, and we need food again.

Additionally, our Macros and Micros Masterclasses can help you ensure you’re getting the macro and micronutrients your body needs to rest, replenish, and support your adrenal glands. You might just get to crank up the energy from carbs and fat to give yourself more fuel.

3. Eat at maintenance energy or higher.

The amount of fuel you require fluctuates with the amount of stress you’re under (scroll back up for all the different types of stress). All of them can increase the energy your body requires to function optimally, and they may increase the frequency at which you need to eat. To begin, start by consuming your maintenance calories divided into three solid meals. You can use our Macros Calculator to determine your approximate maintenance calories. From there, you can determine when to eat using the Data-Driven Fasting method.

If you find you are gaining weight at maintenance, you may need to reverse diet and bring your calories up from where you left off. While we don’t currently have a program for this, you would essentially track for a week at your normal diet to determine the number of calories you eat without intervention. From there, you would select the number of calories you need at maintenance and slowly add around 100 calories per week until you’re at your calculated intake.

4. Consume some carbs AND fat (in the case of adrenal fatigue), and ensure you’re hitting your protein goal at each and every meal.

Protein, fat and fibre are crucial for blood sugar stabilisation. While eating carbs AND fat is the opposite advice we’d give to someone with hyperglycaemia and T2D, introducing some carbs can be helpful if you’ve been driving your blood glucose low for a long time. In a stressed and taxed state, your body’s glycogen stores are often depleted more readily than in someone who is in a rest-and-digest state.

5. Consume water with electrolytes.

Minerals are like the batteries of your adrenals. When you are chronically stressed, your body burns through key electrolytes like sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium. These are especially critical for you if you struggle with something like high or low blood pressure from stress or POTS from adrenal fatigue. You can check sip on our electrolyte cocktail recipe throughout the day, and you might also consider hitting our ONIs for each electrolyte.

6. Avoid highly strenuous exercise.

Yes, we know; these exercises might feel addicting and challenging to give up! Want to know why? When you engage in them, your body releases tons of stress hormones like epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol to get you through it. If you’re in adrenal burnout, this flood of stress hormones will likely give you the energy and power to function. However, you might not feel so good in the hours after, or your sleep might suffer. If you’re experiencing these adverse symptoms, try toning down your exercise output.

7. Try some rest days.

Instead of working out multiple days back-to-back, try working out one day and taking the next day off (i.e., working out every other day). If you still feel taxed after your workout, try working out every other day. You might even have to put the brakes on things for a few weeks to let your body heal completely. Later, you’ll have more energy to get back into it with renewed vigour.

8. Sleep at least eight hours per night.

Whether you’re trying to heal your body from adrenal imbalances or not, this should be a priority up there with nutrient density and satiety.

Research shows that one poor night’s sleep can alter blood sugar regulation and inhibit your decision-making regarding food. Additionally, insufficient sleep is linked to higher incidences of all-cause mortality (i.e., death from all causes), cancer, autoimmunity, and diabetes.

It’s best to get at LEAST eight hours of sleep time (not in-bed time scrolling on your phone!). And while we’re talking about phones, try and keep your eyes away from the blue light of your TV, iPad, or other devices to ensure you sleep more soundly!

9. Avoid caffeine before your first meal of the day or in the afternoon.

While it’s delicious, caffeine—like that found in green and black teas, coffee, energy drinks, and pre-workouts—is a stimulant and can trigger the release of stress hormones.

If you rely on caffeine, this is an even bigger indication that you likely need to back off; you should have the energy you require to get through the day on your own and not with the help of substances! Try and get down to one cup or none.

Summary

- If your weight loss is stalling or you have stubborn fat that you can’t seem to lose, you might consider evaluating the state of your adrenals.

- The adrenal glands are in charge of making stress hormones in times of need. Regulating your body’s stress levels and supporting it with a healthful diet and lifestyle is critical for regaining a regulated metabolism.

- While it’s great to give your body enough stress to change and grow, overdoing it can be counter-productive in the long term.

- This may require resting, taking time away from the gym, eating more calories, and practising stress management until you recover.

More

- Reactive Hypoglycaemia: Symptoms, Causes & Dietary Solutions

- Waking Up with High Blood Sugar? It Might Be the Dawn Phenomenon.

- How Much Weight Should I Lose Per Week?

- Blood Sugar, Insulin and What to Eat for Each Phase of Your Monthly Menstrual Cycle

- Data-Driven Fasting: How to Use Your Blood Glucose as a Fuel Gauge

- Macros Masterclass

Thank you Marty for a very thorough article.

My personal journey with Type One Diabetes has included bsl management challenges from the stress of:

1) chronic pain, in my case sciatica, even on maximum dose anti-neuropathic medication – the medication also causing insulin resistance (an operation has solved both)

2) repeated urine infections caused by prostate problems, and continuing 4 months after operation so far

3) the fear/excitement occasioned by watching a horror or thriller movie !!

Who said life was fair ???!!! LOL

our experience (with my wife) is that stabilising blood glucose with diet helps with all of these.

Excellent article! I read somewhere that coffee, cortisol and fat retention were linked and gave up coffee altogether which I am convinced actually helped in my fat loss journey. I hadn’t a full understanding of why until now. Many thanks.

Marty,

My daughter Cate and I met you and thoroughly enjoyed your session in Denver. Thank you very much.

Due to my S4 melanoma I’m getting monthly immunotherapy that about 9 months ago way over-inflamed my pituitary gland and thus has essentially whacked three of my hormones,…thyroids, cortisol, and testosterone.

Accordingly my formerly naturally produced and distributed cortisol is now 10mg of hydrocortisone when I get up and 5mg more at 3:00 in the afternoon. With it being that rigidly supplied, do you see any application of diet factors?

Fasting-wise, due to my seriously seeking Warburg effect melanoma cells suppression, with low blood sugar and high ketones, I intermittently fast five days a week with only one evening meal per day. And every month I extensively fast three days,…one day before immunotherapy, the day of it, and the day after it.

Even with my regular fasting and therapeutic ketosis (20 grams of carbs/day) effort it is an absolute bear to keep blood glucose 85ish or less and ketones 3ish or more. Any thoughts on making the glucose as low as possible and the ketones as high as possible?

Thanks again for sharing your brilliance, and your caring Marty! And once again, a thrill for both Cate and me to meet you!

Thanks for the kind words. It was great to meet you in Denver. It’s so good to see you thriving in spite of the cancer. You’re a real inspiration!

Brilliant thorough article Marty. I work with police officers who struggle with stress and all the things associated with it – I’ll give this article to them to help their understanding – thanks again

wonderful. thanks Cas! the police certainly have a tough job!

This puts a new light on why I gained so much weight when my husband was going thru chemo and previous weight gain periods with very stressful careers. Thank you so much for what you do.

cheers. managing stress, cortsiol and dopamin is a big part of the satiety equation.

This article is very informative. I just wish that more people knew it applied to them.

I’ll use myself as an example: When I found intermittent fasting, it made total sense to me and I loved how I could “wing it” when it came to meals and eat what I wanted and saved money from not eating as much and the scale was moving, albeit slowly, in the right direction. Until it wasn’t. That was how I found you.

Now I had heard that there were certain individuals that SHOULD NOT FAST. Well, I wasn’t pregnant or breastfeeding, didn’t have a previous eating disorder and nobody ever told me that my adrenals were malfunctioning. I didn’t think I had that much stress in my life. I don’t have kids, I have a happy marriage and I had even taken less stressful jobs (making less money of course) to eliminate those stressful environments.

But, after all this time it has been brought to my attention that not only am I actually very stressed from daily life (work, traffic, parents health, etc.) and past traumas that have gone unresolved putting me in a constant “fight or flight” status which has, as recent saliva tests have confirmed, drained my adrenals.

If you are someone like me, who has many of the symptoms listed in this article, please consider taking the steps also listed above in order to regain your health. I am a work in progress. Now that I know what is really happening, it is a relief, but also another thing to possibly stress over, LOL. But, I am committed to healing my body AND my mind at MY pace.

Thank you Marty, for all you do 🙂

Fasting is an aggressive form of energy restriction, which is a stress. In our classes we encourage people to manage their total stress load. Progressive overload and incremental changes always work best without pushing the body to rebounding.