Are you tired of diets that leave you hungry and unsatisfied? Yearning for a way to eat less without feeling deprived? Look no further! We’ve spent five years decoding the secrets of satiety per calorie, and we’re ready to share our findings.

In this article, we’ll reveal:

- How to quantify food properties for ultimate satisfaction.

- Foods and meals that maximize satiety per calorie, keeping you full and content.

Say goodbye to endless cravings and hello to an intentional, fulfilling way of eating. Join us on a journey to transform your relationship with food and achieve your wellness goals effortlessly. Your path to lasting satisfaction begins now.

- What Is Satiety?

- Satiety Per Calorie

- Eating TO Satiety vs FOR Satiety

- How Long Do You Want to Feel Satiated?

- What Are the Most Satiating Foods Per Calorie?

- What Are the Most Satiating Meals?

- It’s Often Best to Start Slowly

- Protein %

- What Makes Food Less Satiating Per Calorie?

- Which Foods Provide the Least Satiety?

- Other Factors that May Influence Satiety

What Is Satiety?

Satiety is the absence of hunger and desire to eat after consuming a food or meal.

When you feel satiated, you are comfortably full. You are no longer dreaming of raiding your pantry or polishing off those leftovers in the fridge. Instead, you can get on with your day without thinking of food for hours until hunger returns, and you eventually want to eat again.

Satiety Per Calorie

To improve your metabolic health and lose weight sustainably without constantly battling hunger, you need to find a way to increase the satiety per calorie of the food you eat. This will empower you to feel satisfied with less energy.

Eating TO Satiety vs FOR Satiety

Most people simply eat TO satiety rather than FOR satiety.

Let me explain.

Because you have limited space in your stomach, there is a limit to the quantity of food you can eat in one sitting. Eating a lot of energy-dense, ultra-processed junk food TO satiety will make you feel full. However, unfortunately, you will have consumed a LOT of calories to feel satisfied, and you will probably feel hungry again before long.

Rather than eating to satiety—or until your body says, ‘I’m full!’—to lose weight and improve your metabolic health, you need to eat for satiety. To do this, you need to choose foods and meals that provide you with a higher satiety per calorie. This will not only allow you to feel satisfied for longer but also allow you to consume less energy and lose weight.

- Eating to satiety = mindless eating until the volume of your stomach tells you no more.

- Eating for satiety = intentionally prioritising foods that provide greater satiety per calorie across the day.

As you will see below, using data from people like you, living and eating in the real world, we have reverse-engineered overeating and identified properties of food that empower us to feel full for fewer calories.

How Long Do You Want to Feel Satiated?

When discussing satiety, it’s important to understand that different foods will help you feel satiated over different timeframes.

- Short-term satiety is the feeling you get from foods after eating a bulky meal with lots of fibre or water. Your belly is full, and you’re stuffed, so you can’t eat anymore. But unfortunately, depending on what you ate, this satiety can be short-lived.

- Long-term satiety means you don’t think of food for several hours after eating. Our analysis shows that longer-term satiety occurs when you provide your body with the essential nutrients your body requires, particularly the amino acids that makeup protein.

As we will discuss further below, protein and fibre impact satiety and how much we eat across the day.

So, while high-fibre, lower energy-density foods fill us up in the short term, foods that contain more protein and minerals crush our cravings and tend to keep us satiated for the longer term.

For best results, you want to strike a balance between foods that provide both long-term and short-term satiety that you also enjoy eating.

What Foods Provide Short-Term Satiety?

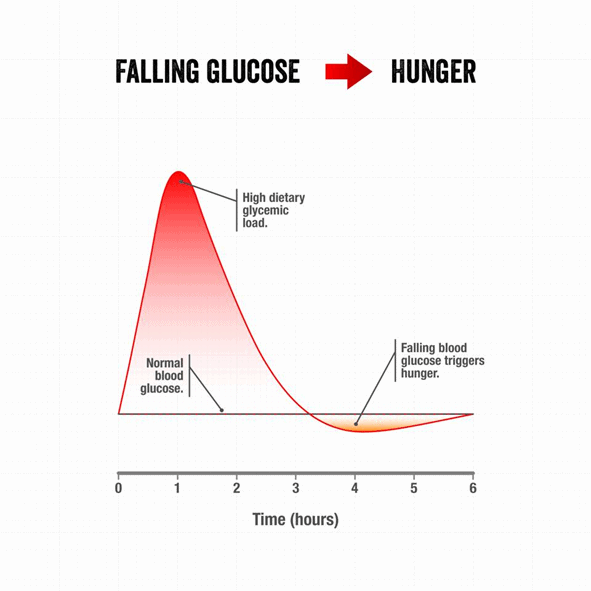

You may be surprised to learn that refined carbohydrates provide the greatest short-term satiety. These rapidly digesting foods raise your blood sugar and insulin quickly, causing your appetite to switch off. However, this only lasts a couple of hours until your glucose comes crashing down and you feel compelled to eat again to bring your glucose back into the normal range. Unfortunately, this blood sugar roller coaster leaves many people feeling like they are ‘‘addicted to food’.

To avoid this ‘reactive hypoglycaemia’ and the binge response that often follows, we suggest that people in our programs dial back their intake of refined carbohydrates if they see their glucose rise by more than 30 mg/dL or 1.6 mmol/L after they eat.

Foods containing a lot of fibre and water will also provide you with short-term satiety if you eat enough. Their sheer volume will stretch your stomach to the point you can’t eat more.

But once you’ve digested them after a couple of hours, you will feel hungry again and compelled to eat again. For example, a watery soup or a big salad may leave you feeling stuffed but hungry again before too long.

There’s not much point in achieving short-term satiety if these foods leave you ravenous and prone to overeating energy-dense comfort foods only a few hours later!

Long-Term Satiety

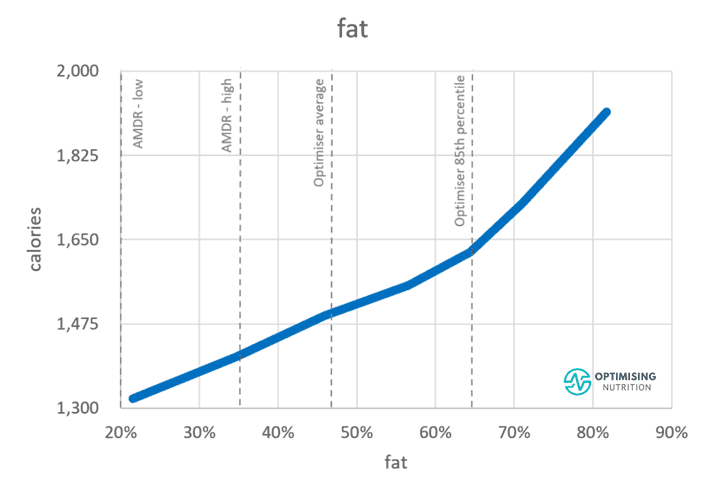

High-fat foods tend to digest more slowly, keeping you full for longer. But because fat is more energy dense than fibrous green-and-leafy vegetables, you need to consume a lot more energy to feel satiated.

Many people subjectively report that a very high-fat diet is satiating, but how many calories did they eat to achieve that satiation?

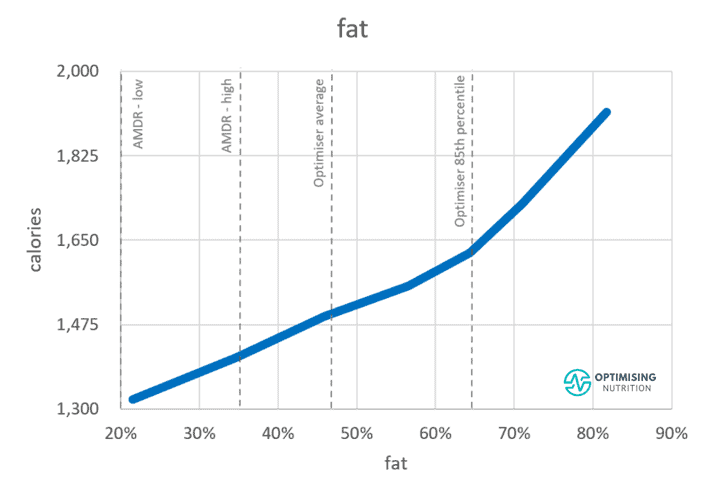

But we can’t avoid fat altogether because it comes packaged with foods that also contain protein. However, the reality is that fat is the least satiating of the macronutrients. As shown in the chart below from our satiety analysis, calorie for calorie, we eat more when our diet contains more fat.

Satiety Per Calorie Across the Whole Day

To eat less and manage your appetite over the long term, you need to find the foods that keep you satisfied throughout the day, every day.

Unfortunately, most studies investigating satiety simplistically measure how much people eat at their next meal, so they only consider short-term satiety. This leads to recommendations for low energy density, low fat and often low protein foods packed with heaps of fibre and water.

Over the past five years, we have amassed 136,514 days of data from more than forty thousand people using Nutrient Optimiser. This unique dataset allows us to understand the properties of food that align with eating less across the whole day.

Using this data, we have developed our Satiety Index Score using multivariate regression analysis to rank foods based on how many calories of each food or meal you are likely to eat if that’s all you ate for the whole day.

We’ll dig into how we developed the Satiety Index Score later. But first, let’s show you the foods and meals that provide the most satiety per calorie!

Protein and Micronutrients

One of the primary findings from our research and analysis is that foods that satisfy your cravings for longer tend to contain more of all the essential nutrients, particularly the amino acids that makeup protein.

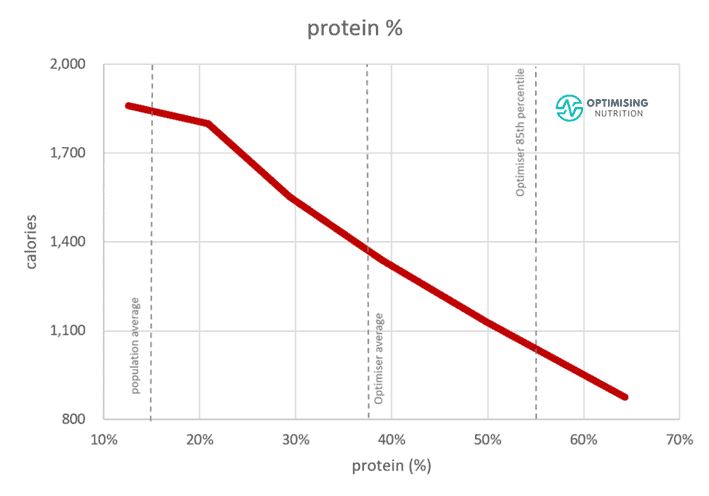

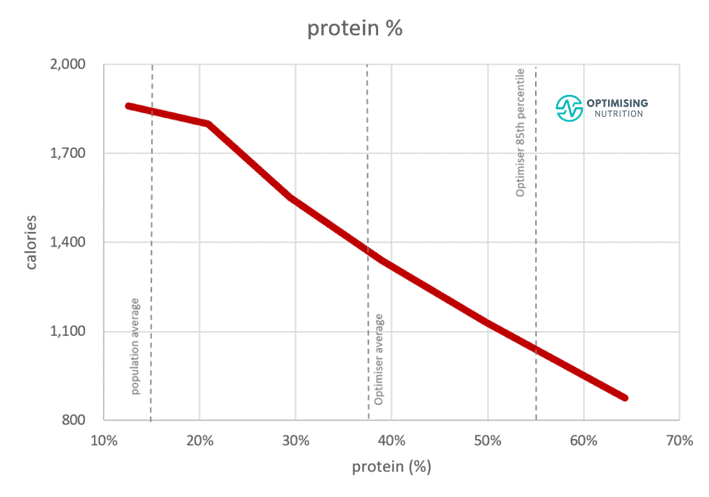

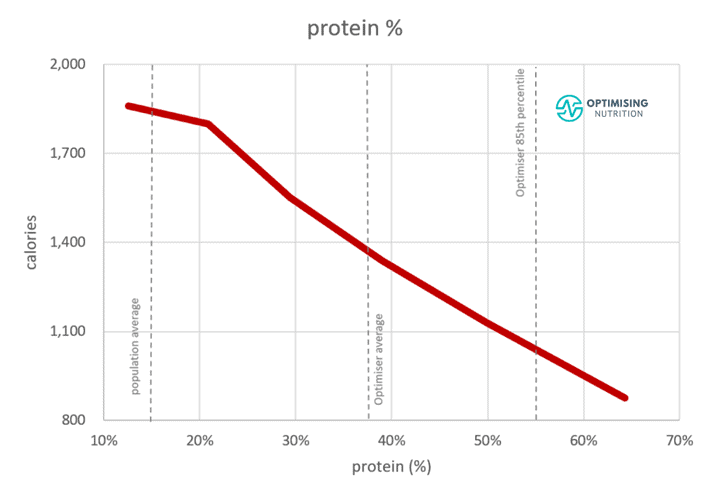

As shown in the chart below, protein % is the most dominant factor in how much we eat across the day. However, fibre and other nutrients, particularly the larger minerals (e.g., calcium, potassium and sodium), also appear to play a part in satisfying our cravings. In the end, nutrient density and satiety are intimately related.

Like a baby crying for its bottle or a dog whining for food, your appetite is your body’s way of getting you to eat all the nutrients your body needs to thrive. So, when we look at long-term dietary patterns in our data, we find that maximising satiety per calorie comes down to satisfying your cravings for the nutrients it needs from food without excess energy from fat or non-fibre carbohydrates.

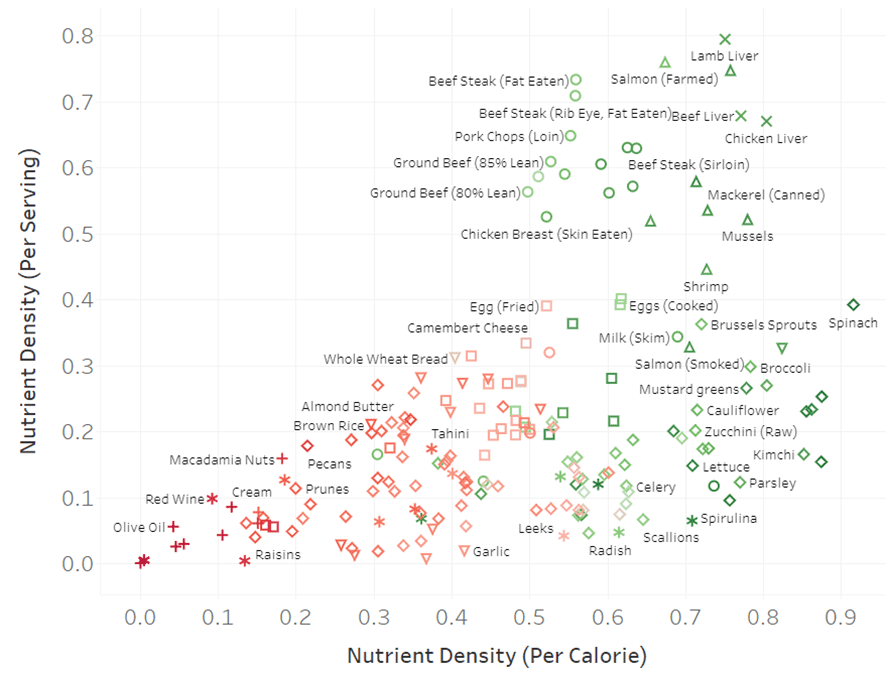

What Are the Most Satiating Foods Per Calorie?

To explain what this means for our food choices, the chart below shows a range of popular foods plotted on the landscape of nutrient density (per calorie) vs nutrient density (per serving).

- Foods shown in green towards the top right have a higher Satiety Index Score.

- Conversely, foods in red shown towards the bottom left have a lower Satiety Index Score.

You can click here to dive into more detail in Tableau on your computer screen.

- Foods with the highest nutrient density per calorie, shown towards the right of this chart, tend to provide greater short-term satiety per calorie. But if you try to fill your plate with only non-starchy vegetables like lettuce and spinach, you may be stuffed in the short term, but you may be hungry before long because you can’t get enough energy to get you through the day.

- Meanwhile, the foods at the top of the chart provide more nutrients per serving. You can use these foods to build the foundation of your daily diet to get enough protein, energy, and the other nutrients you need. These foods provide greater long-term satiety as well as plenty of nutrients.

Plants vs Animal Based Foods

Quantifying foods based on the nutrients they contain removes the all-too-common dichotomy between plant-based foods vs animal-based foods. While some people prefer animal base foods and others prefer plant-based foods, we find people thrive when they find a balance of both that they enjoy.

As you add more of the high-satiety foods shown in green, you should also reduce or avoid the low-satiety, energy-dense foods shown in red towards the bottom left. But as you begin giving your body the nutrients it needs; this usually happens automatically as it loses interest in less-than-optimal foods because they have already satisfied their cravings with nutritious foods.

Click here to download our printable food lists tailored towards various goals.

Now we know what contributes to satiety, let’s dive into each of the main food groups.

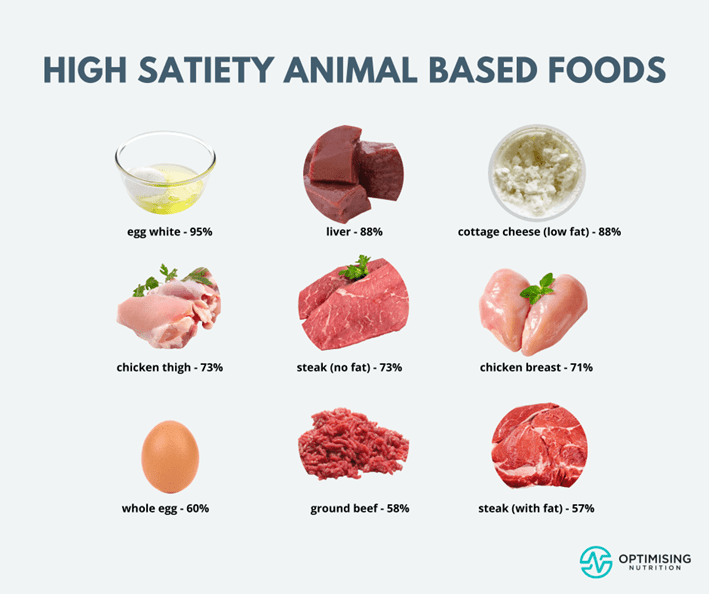

Animal-Based Foods

The chart below only shows how animal-based foods stack up in terms of satiety.

Animal-based foods tend to be pretty satiating across the board. However, the more processed an animal-based food gets (i.e., ice cream, luncheon meats, and hot dogs), the more fat it contains, the less satiating it is. For more details on finding the right balance between protein and fat, see High Protein vs High Fat: What’s Ideal for YOU?

Seafood

In the chart below, we’ve detailed the nutrient density of seafood. As a general rule, seafood tends to be highly satiating and nutritious.

Similar to animal-based foods, most seafood in its unprocessed form is quite satiating. However, breading and frying it—like calamari and battered fish—dilutes its satiety score by adding extra energy from refined fats and carbs.

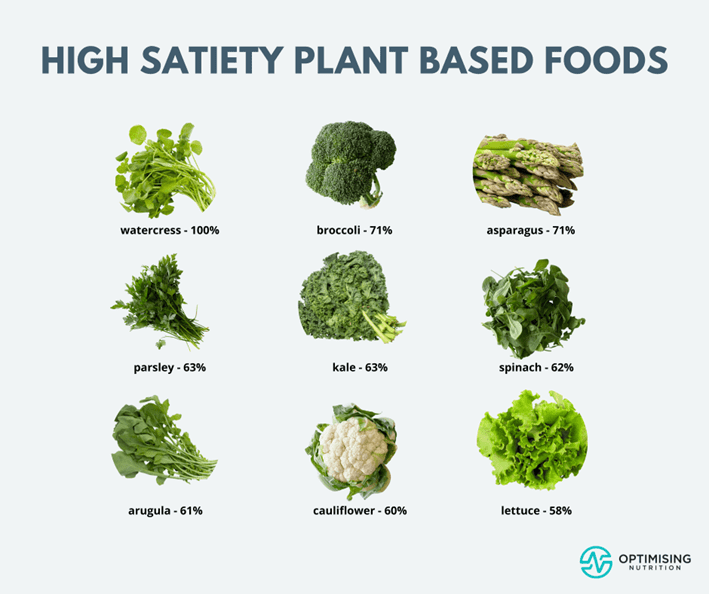

Plant-Based Foods

Lastly, we have plant-based foods. From broccoli, spinach, asparagus and chard in the top right corn to sugar, bread and ketchup in the bottom left, the plat-based category covers a broad spectrum of foods.

Although you can create a satiating, nutrient-dense, plant-based diet, simply defining your diet as ‘plant-based’ does little to help you avoid the worst of the nutrient-poor ultra-processed foods.

Based on our analysis, the most satiating plant foods per calorie tend to provide a substantial amount of nutrients per calorie. Most of these foods include nutritious, non-starchy green vegetables, which are some of the densest sources of harder-to-find nutrients like vitamins A, C, E, and K1, and minerals like magnesium, calcium, copper, and iron. But even if you’re in a hurry to lose weight, it will still be hard to get enough protein and energy from these foods alone.

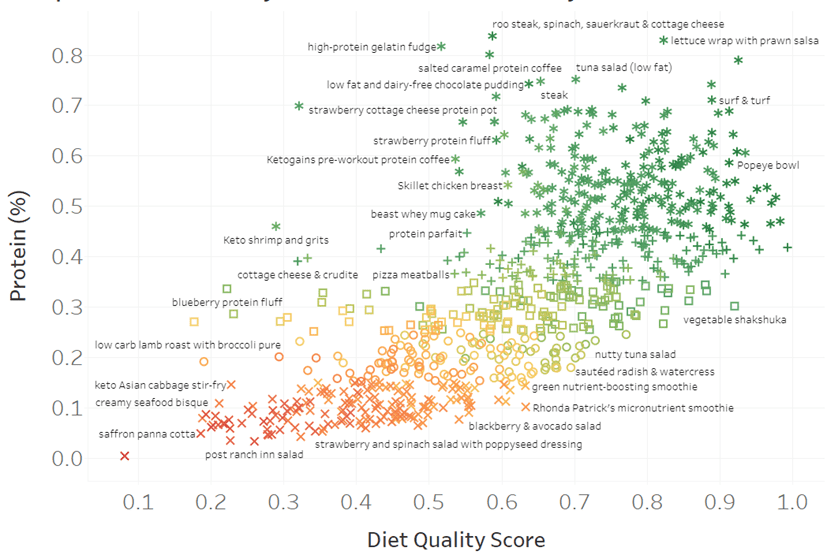

What Are the Most Satiating Meals?

While it’s interesting to look at the most satiating foods, most of us don’t consume individual foods; we combine them to make meals that balance our macronutrient and micronutrient needs.

The chart below shows the 1016 recipes we have analysed on the landscape of our Diet Quality Score vs protein %.

- Again, the recipes shown in green have the highest Satiety Index Score, meaning they will keep us fuller over the long term because they provide greater satiety per calorie.

- Conversely, the ones shown in red provide less protein and the least satiety per calorie.

Again, you can click here to explore the detail of this chart in Tableau. You will see all the details if you click on the dish’s name. At the bottom of the window, you can click ‘click to view recipe’ to view the recipe in your browser.

It’s Often Best to Start Slowly

Over the years of working with people in our Macros Masterclasses and Micros Masterclasses, we’ve found that most people experience the best long-term success when they progressively level their nutrition rather than jumping from one extreme to another.

For example, you may not enjoy jumping to 80% protein recipes on day one if you’re currently following a high-fat keto diet or a low-protein standard western diet. Hence, jumping from one extreme to another is rarely sustainable.

Most people do much better when they level up their nutrient density and protein % incrementally. Aggressive overnight changes rarely last, and you only need to make enough change to see sustainable results (e.g. a weight loss of 0.5 to 1.0% per week).

So, enjoy the progress and success; you don’t need to go from zero to hero overnight!

In our Macros Masterclass, we guide Optimisers to progressively level up their satiety by breaking our NutriBooster recipes into four levels:

- Level 1 – 15 to 25% protein

- Level 2 – 25 to 35% protein

- Level 3 – 35% to 45% protein

- Level 4 – Greater than 45% protein

For reference, the average protein intake is around 12-19% of calories.

- The level 1 recipes would be ideal for most people starting from a standard western diet aiming for healthy weight maintenance.

- Level 2 would be ideal for gentle weight loss.

- Level 3 would be great if you’re enjoying Level 2 but find you want to push a little bit harder.

- Finally, the level 4 recipes are ideal for rapid fat loss over a short period (i.e., an ‘aggressive cut’). While they will provide more nutrients and the greatest satiety per calorie, they may be a little hardcore for most people starting their journey of Nutritional Optimisation because they provide minimal energy from fat and carbs.

If you’re a member of our Optimising Nutrition Community, you can learn more about our NutriBooster recipe books and check out samples here.

Now we’ve shown you which foods and meals provide more satiety per calorie, let’s finish off by delving a little deeper into our analysis to see what makes a food or meal more satiating per calorie.

Protein %

Our analysis has repeatedly shown that protein % is the most critical variable for whether or not someone will feel satiated over the long term. Our appetite is constantly working to find the right balance of nutrients and energy. Because protein is critical, getting adequate protein is the first step to optimising this relationship.

As the chart below shows, people consuming a higher protein % tend to consume 62% fewer calories than those who consume the lowest protein %.

But protein isn’t the only factor influencing satiety; as discussed below, we also see a statistically significant response to foods containing more nutrients like fibre, potassium, calcium, and sodium per calorie.

For more on the impact of micronutrients on satiety, check out The Cheat Codes for Optimal Nutrition, Satiety, and Health.

What Makes Food Less Satiating Per Calorie?

In practice, most people find they don’t need to eat a lot more protein to increase their satiety per calorie throughout the day. Instead, they make more progress by reducing dietary fat and non-fibre carbohydrates while prioritising protein and minimally processed foods. This leads to an increase in protein %.

To increase your protein % successfully, you need to gradually reduce energy from fat and non-fibre carbs. But, increasing your protein % too quickly might make it hard to adhere to. Even if you’re in a hurry to lose weight, you still need some energy from your diet. Carbs and fat are relatively accessible energy sources, whereas your body has to work a bit harder to produce energy (ATP) from protein.

While protein is the most satiating macronutrient, fat, fibre, and carbohydrates also have a unique satiety response. Let’s quickly look at how each one of them influences how full you feel (or don’t).

Fat

Although some people recommend ‘eating fat to satiety’, it may surprise you that fat is the least satiating macronutrient on a calorie-for-calorie basis. Refined fat also contains very few nutrients per calorie or essential vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, and amino acids.

As the chart below illustrates, people who consume more of their energy from fat tend to consume more calories. At the same time, fat tends to accompany protein, which we know is critical for satiety. Hence, it’s hard to eliminate dietary fat completely.

The takeaway is that you can’t just eat more bacon, butter, nuts, or other high-fat foods that contain some protein to increase your protein %. Instead, you must dial back added fat and prioritise lower-fat, high-protein foods. This will increase the amount of protein you’re eating relative to fat, upping your overall protein %

For more details, see Fat – Optimal vs Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR).

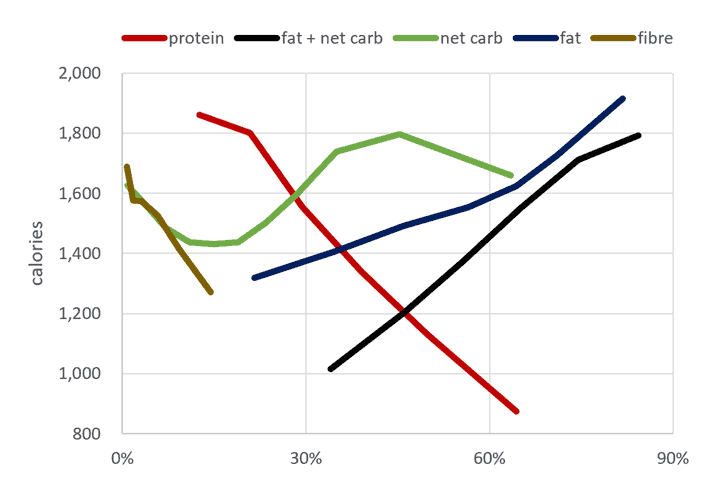

Carbohydrates

While the satiety response to fat is almost linear, our satiety response to carbohydrates is more interesting. As we can see in the chart below:

- we tend to eat the most when we consume foods consisting of about 43% non-fibre carbohydrates with most of the remaining energy coming from fat (this blend of fat and carbs is the signature of modern ultra-processed foods);

- moving from the hyper-palatable blend of fat and carbs to 10-20% carbohydrates aligns with a 23% reduction in calorie intake; and

- our calorie intake also tends to decline again when we get most of our energy from carbs, some of our calories from protein, and very little from fat.

While carbs might cause more fluctuations in your blood sugar than fat, whole-food carbs are not necessarily the enemy, as some people would have us believe! Like fat, carbohydrates are just a source of energy that we can overconsume. For more detail, check out our article, Carbs OR Fat vs Carbs AND Fat.

Fibre

Fibre increases the satiety value of our food, but to a lesser extent than protein %. High-fibre foods are bulky, fill you up, and take a sizable amount of work to digest. Foods that naturally contain more fibre also tend to provide more of the harder-to-find vitamins and minerals. In our programs, we don’t necessarily prioritise fibre, but we find that people who are getting plenty of all of the essential nutrients are also getting plenty of fibre.

For more on fibre, check out Dietary Fibre: How Much Do You Need?

All Macronutrients

To bring it all together, the chart below compares the satiety response to each macronutrient alongside one another. In summary:

- Reducing energy from either fat or carbs will positively affect satiety.

- However, you get the biggest ‘bang for your buck’ when you reduce fat and carbohydrates while prioritising protein and fibre. This leads to an increase in protein % and nutrient density.

Which Foods Provide the Least Satiety?

So far, we’ve focussed on the parameters of our food that align with eating less. But it’s also useful to understand the properties of food that aligns with eating more than we need to.

The table below shows the results of our multivariate regression analysis when we look at the factors that align with increased calorie intake. While some people avoid sugar, saturated fat, starch, or monounsaturated fats, each one aligns with eating more.

| 15th | 85th | calories | % | |

| Sugar (g/2000 cal) | 11 | 71 | 119 | 7% |

| Saturated fat (g/2000 cal) | 20 | 61 | 279 | 16% |

| Starch (g/2000 cal) | 0.8 | 48 | 201 | 11% |

| Monosaturated (g/2000 cal) | 16 | 53 | 225 | 13% |

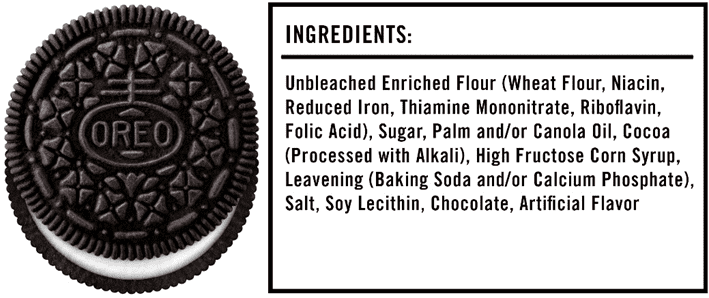

While we undoubtedly need some energy from our food, ultra-processed foods combine several energy sources—like sugar, starch, and processed seed oils—with artificial flavours, colourings, and synthetic vitamins to spruce up the appearance, taste, and nutrition label. This is the basic formula for modern ultra-processed foods.

Avoiding foods that contain a mixture of refined ingredients like grains, added sugar, and oil is perhaps the #1 thing you can do to improve your metabolic health and lose weight. The ingredient list of the Oreo cookie shown below is a prime example.

Although tasty, the Oreo does little to supply you with protein, fibre, or essential nutrients. Unfortunately, you’ll find that most of the packaged foods in the centre isles of your supermarket have a surprisingly similar ingredient list.

Other Factors that May Influence Satiety

Other than the macronutrient content of your food, several other factors align with greater satiety. While their effects are less, they’re also worth mentioning for completeness.

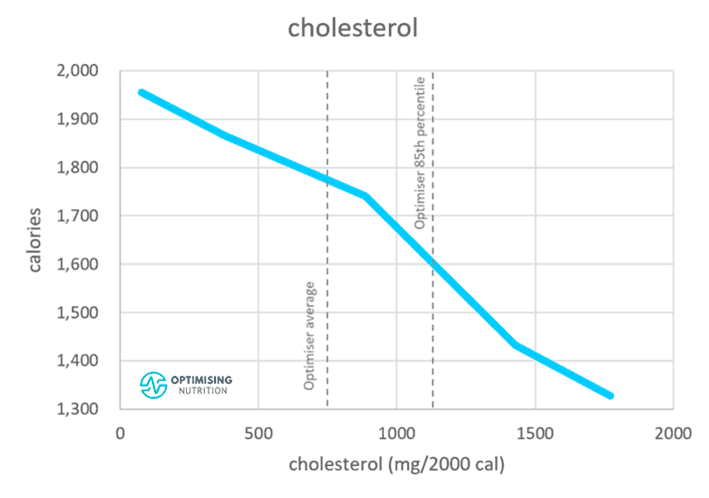

Cholesterol

While some people still believe that cholesterol is a nutrient we should avoid, our satiety analysis shows that foods that contain more cholesterol per calorie tend to be more satiating.

Unfortunately, actively avoiding cholesterol also leads us away from foods that contain more protein and other essential nutrients that align with greater satiety.

When we test the impact of cholesterol in our multivariate analysis, we find that it has a large positive impact on satiety, more than fibre, but less than protein. While cholesterol isn’t an essential nutrient (because our body can make it in the liver), it plays several crucial roles, so it makes sense that we may crave foods that contain more of it.

While there’s no need to go out of your way to consume more cholesterol, there’s no need to avoid nutritious foods that naturally contain it.

For more details, see

- Dietary Cholesterol and Blood Cholesterol: Are They Related?

- Does Eating Fat Make You Fat? The Surprising Truth About Cholesterol and Saturated Fat! and

- Cholesterol: When to Worry and What to Do About It

Hedonic Factors

Anyone who has ever combined carbs and fat would tell you there appears to be something almost magical that occurs when we eat them together, especially if we negate protein and fibre, too. Whether it be French fries, pizza, your favourite cake, or even the classic loaded baked potato, this hyper-palatable combo is guaranteed to make you eat more.

Whether by accident or design, food manufacturers seemed to have taken advantage of the combination of refined starch, added sugar, seed oils, and added flavours, colours, and synthetic vitamins that send us into a feeding frenzy. Some people call this hyperphagic response ‘hedonic hunger’, meaning we eat for pleasure from the dopamine response these foods provide.

While we have tried to model the cumulative effects of this ‘hedonic factor’ that occurs from the combination of sugar, starch, and fat, we’ve found it doesn’t make much of a difference compared to if we consider the factors that positively influence satiety.

For more detail, see Ultra-Processed Food: Modelling The ‘Hedonic Factor’.

Energy Density

As we mentioned earlier, energy density plays a role in short-term satiety. However, voluminous low-calorie foods are often digested quickly. Hence, a watermelon, a head of lettuce, or a big bowl of watery soup may not stop you from overeating energy-dense comfort foods later in the day.

We’ve tried to make energy density work in our Satiety Index Score, but it doesn’t appear to be statistically significant once we consider the other factors. Once you prioritise foods that naturally contain more fibre, potassium, and calcium, energy density seems redundant. Nutrient-dense foods with plenty of protein, fibre and essential nutrients already have a lower energy density.

For more detail, see:

- Low-Energy-Density Foods and Recipes: Will They Help You Feel Full with Fewer Calories? and

- Energy Density vs Protein % for Satiety and Weight Loss.

Viscosity

Viscosity—or how thick a fluid may be, like honey—also may have a small impact on satiety. In other words, solid and high-viscosity foods are more satiating than liquids and lower-viscosity foods.

To put this into perspective, a thick drink that’s a little harder to digest appears to keep you fuller for longer. However, data on the viscosity of whole food is sparse, so it’s hard to use. Viscosity is also unlikely to be relevant over the long term.

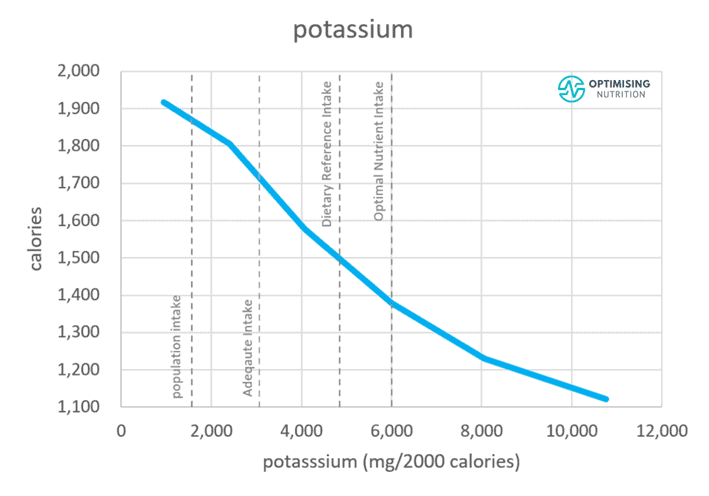

Micronutrients

Like protein, we also see a nutrient leverage effect with most other essential nutrients. Foods that naturally contain more minerals—like potassium, calcium, and sodium—per calorie tend to be more satiating. Similar to protein, it seems we may crave these essential nutrients because they are critical for bodily function. Hence, we will continue eating until we get enough of them. For example, the chart below shows that as we consume foods with more potassium per calorie, we tend to eat less.

The table below shows the results of our multivariate analysis of 136,514 days of data when we also consider the micronutrients. While protein still dominates, the larger minerals (like calcium, potassium and sodium) also play a role in the satiety equation. Whole foods that are harder to overeat tend to contain more of the other essential nutrients we need per calorie.

| 15th | 85th | calories | % | |

| Protein (%) | 19% | 44% | -452 | -30% |

| Fibre (g/2000 cal) | 11 | 44 | -87 | -5.7% |

| Calcium (mg/2000 cal) | 470 | 1909 | -68 | -4.5% |

| Potassium (mg/2000 cal) | 1891 | 6043 | -57 | -3.7% |

| Sodium (mg/2000 cal) | 1488 | 5179 | -47 | -3.1% |

| Total | -46.7% |

When all of the statistically significant factors are considered together, we find that:

- People consuming 44% of their energy from protein consume 30% fewer calories than those who consume 19% protein.

- People getting 44 grams of fibre consumed 6% fewer calories than those who only consume 11 grams of fibre;

- People eating 1.9 grams of calcium consume 4.5% fewer calories than those who consume 0.5 grams of calcium;

- People getting 6 grams of potassium consume 3.7% fewer calories than those who only get 1.9 grams of potassium; and

- People eating 5.1 grams of sodium consume 3.1% fewer calories than those who only consume 1.5 grams of sodium.

While our analysis quantifies the average satiety response to the various nutrients based on the data we have from forty thousand people, each person likely has their own priority nutrients they crave more than others due to their current diet, health conditions, and their unique metabolism.

In our Micros Masterclass, we guide Optimisers to identify their ‘priority nutrients’ they are getting less of. They then use Nutrient Optimiser to identify the foods and meals that contain more of them to achieve a balanced diet at the micronutrient level.

To identify the nutrients your diet is currently lacking and that you need to prioritise, you can take our free 7-Day Nutrient Clarity Challenge.

Summary

- Satiety is the feeling of fullness you get after eating a food or meal.

- It’s important to consider both short-term satiety—or how full you feel in the short term after consuming a meal—and long-term satiety—or how full you feel in the many hours after a food is eaten.

- Most people eat TO satiety but find themselves hungry again soon before long. By making more informed food choices, we can eat to achieve greater satiety across the day.

- The most significant factor influencing satiety per calorie across the day is the per cent of total protein—or protein %—someone consumes.

- Fibre, along with other nutrients, also play a role in helping us to eat less and satisfy our cravings with less energy.

- In contrast, foods containing sugar, starch, and monounsaturated fat align with a higher calorie intake. This is the basic formula for modern ultra-processed foods.

- You might want to jump into an extremely low-carb, low-fat, high-protein, high-fibre for rapid results. However, most people have better long-term success when they progressively dial back on their carbs and fat while slowly increasing their protein %.

More

- High Satiety Index Foods

- Sugar, Carbs, and Beyond: Decoding Cravings and Food Addiction

- Satiety Per Calorie vs Calories In – Calories Out

- One Nutrient Density and Satiety Chart to Rule Them All

- Macros Masterclass

- Micros Masterclass

- 7-Day Nutrient Clarity Challenge

- The Food Satiety Index

- Optimised Food Lists