So much of our modern ‘nutrition advice’ focuses on avoiding ‘bad’ foods or nutrients.

But as you will see, many of these beliefs become irrelevant when we prioritise nutrient density. Dive into a realm where common dietary beliefs are put under the microscope, revealing truths that could revolutionize your approach to nutrition.

This investigative piece uncovers ten prevalent nutritional myths, with a spotlight on carbohydrate misconceptions that have long misled many. As you journey through each myth, you’ll discover a blend of scientific insights and empirical data, equipping you with a clearer, fact-based understanding of nutrition’s impact on your health.

Are you ready to challenge the status quo and redefine your nutritional knowledge? Your pathway to a more informed and healthier lifestyle begins here.

- Nutrition Science is Still a Baby!

- We’re Getting Fatter!

- The Nutrition Data

- Myth #1: Dietary Cholesterol Is Bad for You.

- Myth #2: Saturated Fat Is a ‘Bad’ Fat.

- Myth #3: Monounsaturated and Polyunsaturated Fats are ‘Good’ Fats.

- Myth #4: Fat Does Not Make You Fat.

- Myth #5: Only Carbs Make You Fat.

- Myth #6: Salt Is Bad for You.

- Myth #7: Calories Don’t Count.

- Myth #8: Sugar Is Public Enemy #1.

- Myth #9: Red Meat and Eggs Are Bad for You.

- Myth #10: Macronutrient Percentages Matter.

- Bringing it All Together

Nutrition Science is Still a Baby!

Nutrition science is still relatively young in the grand scheme of things.

We still have a long way to go before nutrition can be considered a hard science like physics, maths, or chemistry, where we can know things with a high degree of accuracy.

Unfortunately, it’s hard for nutritional research to move quickly because it’s unethical to use A/B testing on humans straight out of the gate. Getting an experiment to the status of a controlled trial takes time and money. Thus, we often rely on nutritional epidemiology to study the impact of nutrition and diet.

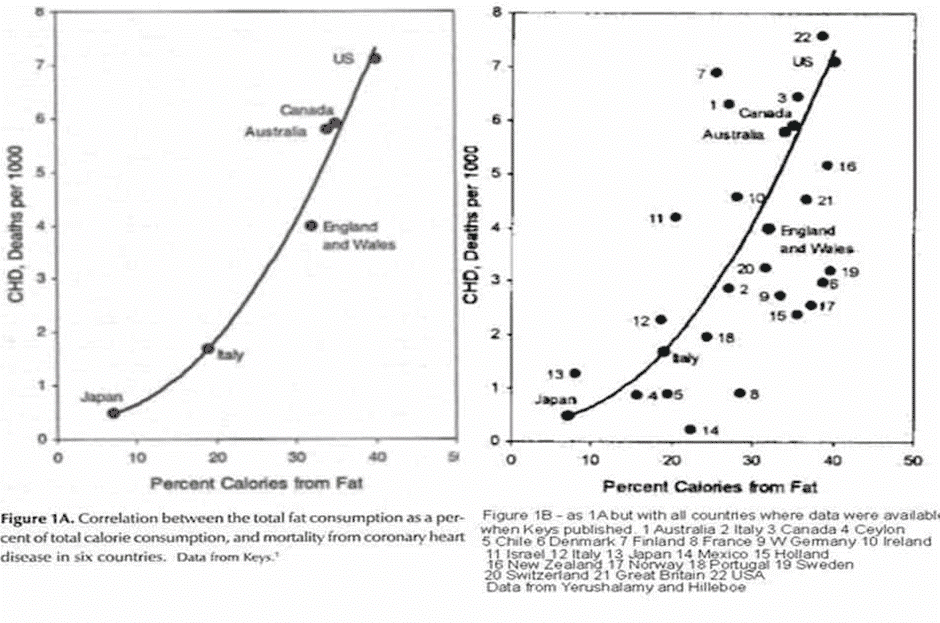

Nutritional epidemiology compares the health and habits of different populations. Ancel Keys’ Seven Countries study is an (in)famous example.

While epidemiology can be helpful, these studies cannot show causality. Epidemiology only suggests relationships between particular components and a specific health outcome.

Most of us are bad at recording what we eat, so it can be hard to study the effects of nutritional interventions. In the absence of hard data, our dietary views are often influenced by:

- tradition,

- religious beliefs,

- ethical convictions, and

- financial conflicts of interest (e.g. advertising from food companies and studies sponsored by drug companies).

The global population has been part of some large-scale nutritional experiments over the past 50 years that have dramatically changed our health and how we eat.

Rather than looking at different populations or small, controlled experiments, we now have a significant amount of longitudinal data that we can use to evaluate how our nutritional beliefs are working out for us.

We’re Getting Fatter!

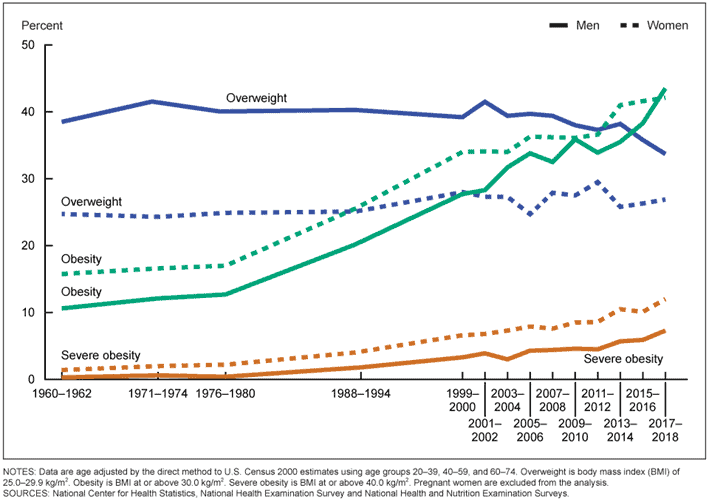

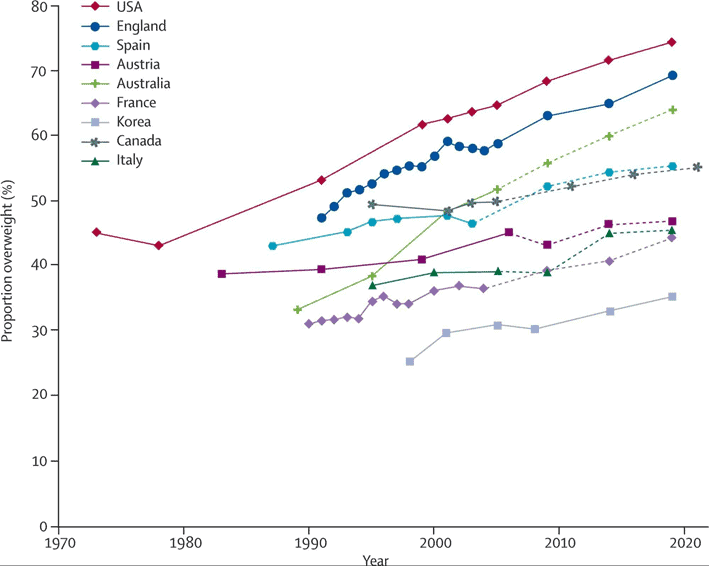

One thing we all can agree on is that the global population is getting fatter. The chart below shows the obesity rates published by the U.S. Centre for Disease Control.

In 1960, only about 13% of us were considered obese with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30. Fast forward to 2018, and about 42% of Americans were overweight. During this time, the proportion of Americans suffering severe obesity, with a body mass greater than 40, jumped from 0.9 to 9.2%!

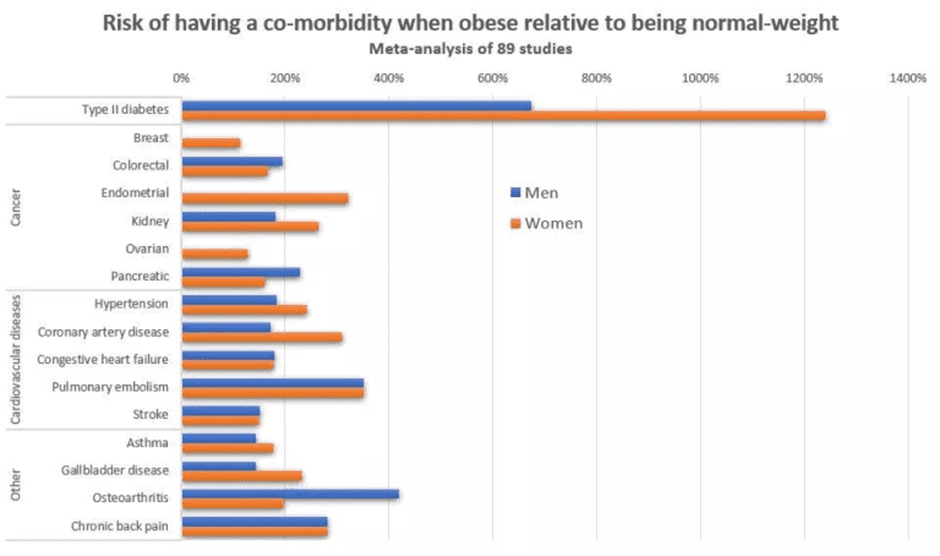

Although many are accepting obesity as the new ‘normal’, most people don’t want to be fat if they had a choice! But it’s not just about appearance. Most people understand instinctively that obesity is not ideal. Obesity increases your chance of having a wide range of metabolic issues that are bad for you, your community, and the economy.

While many factors affect obesity, our food list is likely #1. This article analyses long-term nutritional trends by comparing one hundred years of data against U.S. obesity trends. If you’re not in the U.S., this information is still relevant, as your diet and obesity rates are likely to follow the United States.

The Nutrition Data

The nutrition data used in this analysis is taken from the USDA Economic Research Service. This data shows how our food has changed over the past century.

Observing the long-term trends of humans in the wild can be more helpful than seeing a few individuals for a few days in a controlled metabolic chamber.

While the data has its limitations, it also gives us another viewpoint to test the observations that we can make from other sources. We’re not trying to demonstrate causality. Instead, we’re hoping to understand which beliefs do not align with reality.

Myth #1: Dietary Cholesterol Is Bad for You.

Let’s start with cholesterol as an example of a dietary belief that many have decided is not only useless but detrimental.

Because of Ancel Keys’ work on dietary cholesterol in the Eisenhower era, most people believed that consuming dietary cholesterol directly correlated with blood cholesterol levels, arterial plaques, and heart disease. However, we now understand that:

- there are many risk factors for heart disease,

- dietary cholesterol does not equate to blood cholesterol levels, and

- your liver produces 80-90% of your body’s cholesterol needs whether you eat it or not.

More recent studies have actually shown the negative effects that low cholesterol can have on the body.

Cholesterol is not considered an essential nutrient because your body typically produces it endogenously. If you eat less cholesterol, your body will make more to compensate.

We require cholesterol to synthesise hormones like estrogen, progesterone, testosterone, and cortisol. We also need cholesterol to make bile and build human cell membranes.

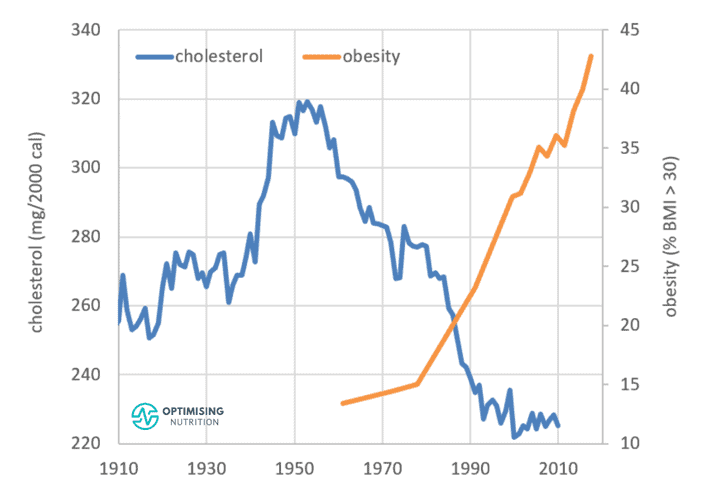

The chart below shows cholesterol available in the food system over the last hundred years overlaid with obesity rates since the 1960s. We can see that the cholesterol in the food system has been declining since the 1950s when we started to ramp up the industrialisation of our food system.

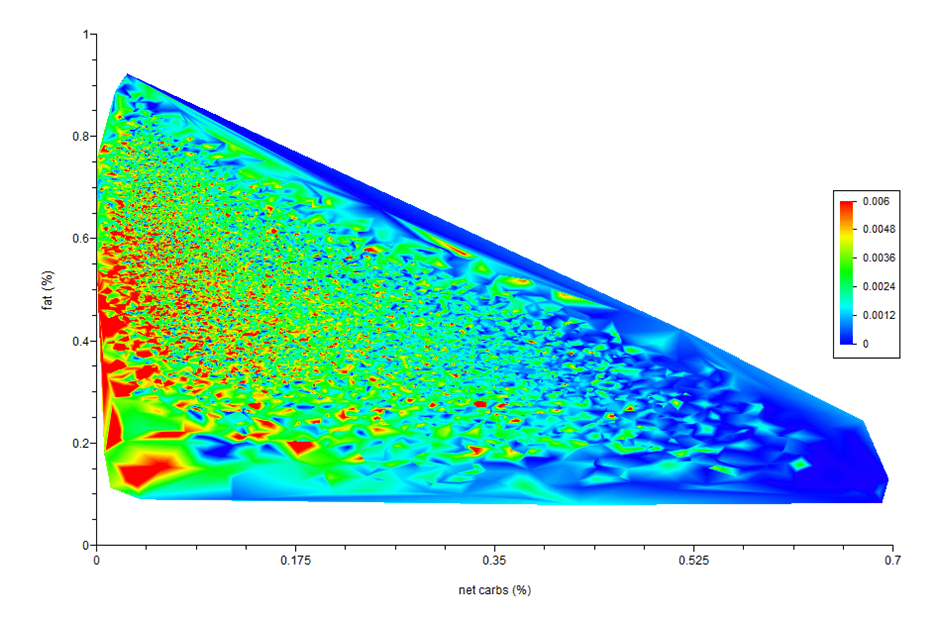

As shown in the heat map chart of net carbs vs fat, cholesterol intake tends to be higher in diets lower in carbohydrates and moderate or low in fat.

Interestingly, our satiety analysis shows that foods with a higher percentage of energy from cholesterol tend to align with a lower overall calorie intake.

This does not mean that you should go out of your way to consume more dietary cholesterol. But instead, you shouldn’t fear nutrient-dense foods that happen to contain cholesterol.

Until recently, we were recommended to limit cholesterol to 300 mg/day, or 200 mg/day if you had a high risk of heart disease. However, due to the lack of evidence for a direct causal relationship between dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease, the Dietary Guidelines Committee recently removed cholesterol as a nutrient of concern.

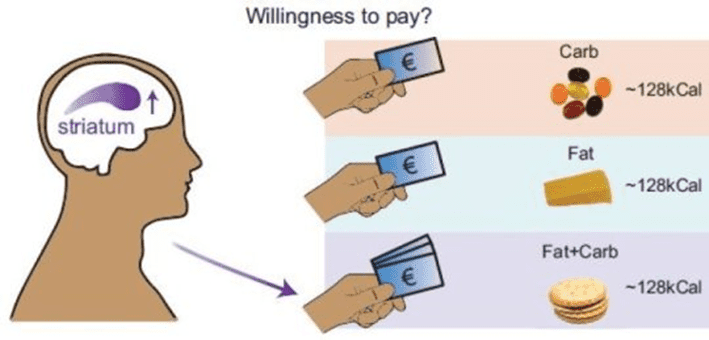

We now better understand that the most significant risk comes when you have both high glucose and high fat in your blood due to a diet that is a mix of excess fat and carbohydrates.

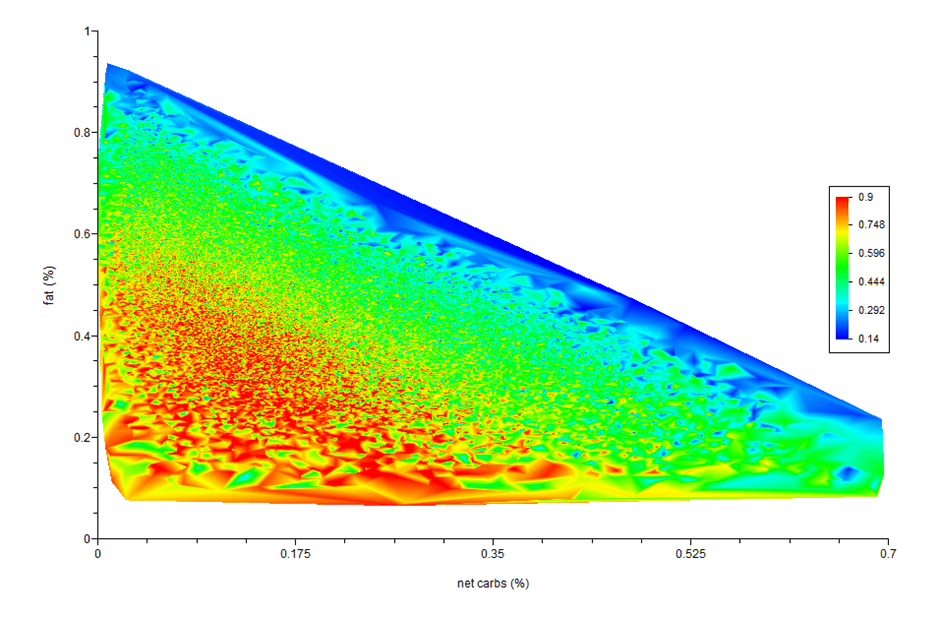

The heat map chart below shows the relationship between carbs, fat and total calorie intake from the analysis of data from Optimisers. The blue area represents low intakes, while the red is high.

Overall, this shows that we tend to eat a lot more when we consume a nutrient-poor diet that is a mix of carbohydrates and fat, which also leads to oxidised LDL cholesterol in our blood.

Bottom line: While you don’t need to prioritise dietary cholesterol, there is no need to fear the cholesterol in otherwise nutritious foods.

For more on cholesterol, see Cholesterol: When to Worry and What to Do About It.

Myth #2: Saturated Fat Is a ‘Bad’ Fat.

Similar to cholesterol, saturated fat mostly comes from animal foods like meat, poultry, and dairy products.

Saturated fat has also caught the blame for many things! Because saturated fat was solid at room temperature, many believed it would harden your arteries and cause heart disease.

As an aside, if your arteries are ever at room temperature, you’d have bigger issues than the amount of saturated fat in your diet.

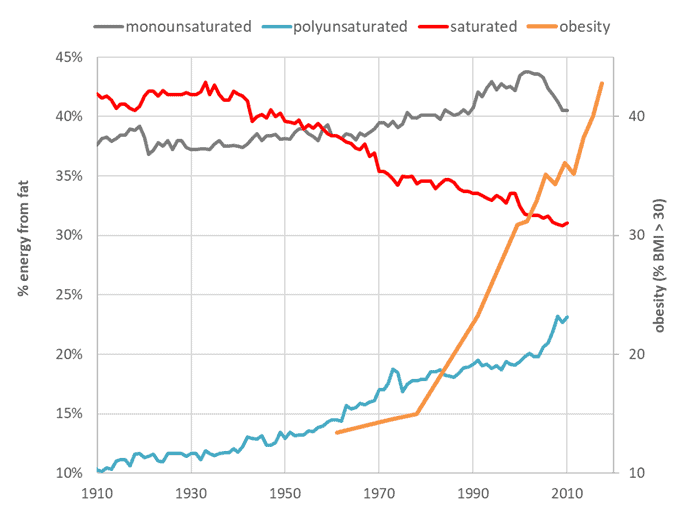

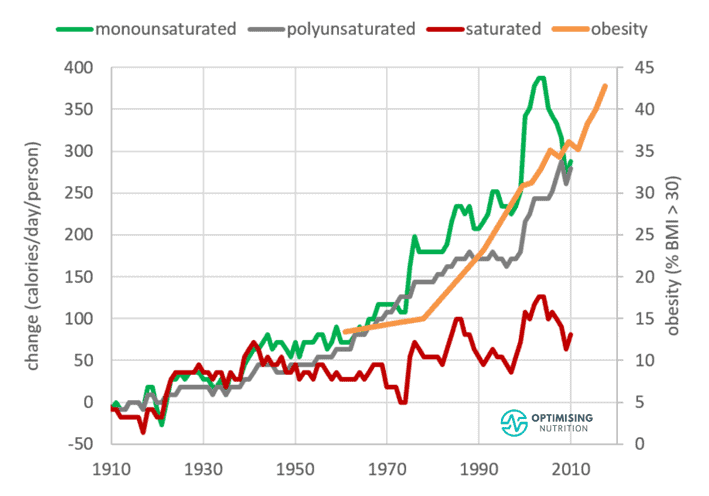

The data from the USDA Economic Research Service shows that saturated fat as a percentage of our total fat intake has been declining for some time. Animal-based fats like butter and lard have been progressively replaced with margarine and industrial seed oils since the 1930s.

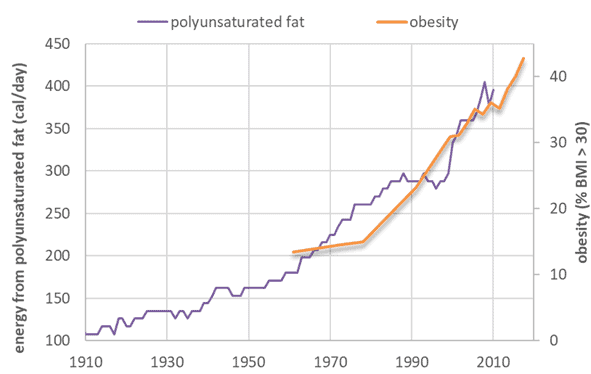

Conversely, a century ago, polyunsaturated only contributed around one-tenth of our fat intake. Now, they provide around a quarter of our fat as they have consistently been on the rise as we followed the expert advice to consume more of the ‘good fats’ like soybean and corn that are high in polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids.

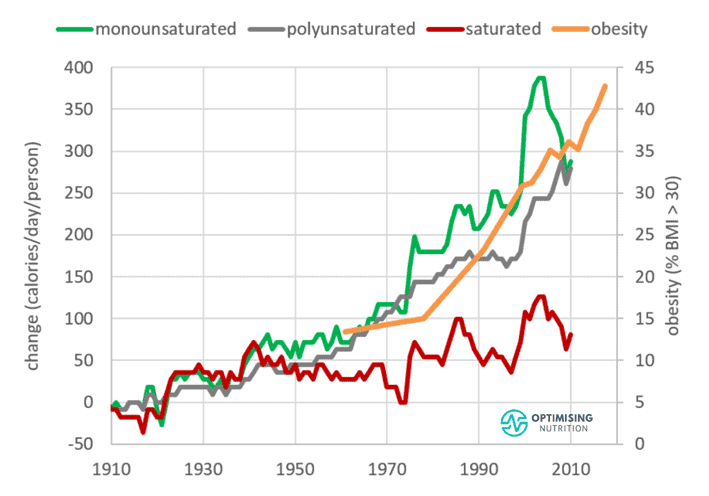

The chart below shows we’re consuming more total calories from all types of fats! While the amount of total calories from fat has climbed, the percentage of energy from saturated fat has trended downwards. Industrialised fats have likely replaced it.

While saturated fat is by no means a ‘free food’, it might not be as toxic as we have been led to believe—at least compared to monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats. Similar to cholesterol, there appears to be no need to avoid otherwise nutrient-dense foods that happen to contain energy from saturated fat. If you focus on getting plenty of nutrients within your calorie budget, you won’t be overdoing the saturated fat.

Myth #3: Monounsaturated and Polyunsaturated Fats are ‘Good’ Fats.

Mainstream advice from the USDA Dietary Guidelines suggests that we should prioritise ‘good’ fats (i.e. monounsaturated and polyunsaturated) in place of saturated fats. But the reality is that all food contains a mixture of poly, mono and saturated fats. The figure below shows that plant-based foods contain more polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fat, while animal-based foods contain more energy from saturated fat.

A large amount of dietary guidance has been driven by ethical or religious convictions against animal-based foods. For a deep dive into the religious and ethical influences on our nutritional beliefs, check out my podcast with Belinda Fettke.

It’s also relevant to note that the United States Department of Agriculture controls the U.S. Dietary Guidelines. It shouldn’t be surprising that their guidance favours agricultural products like corn, wheat, and soy when their explicit mission is to promote U.S. agriculture.

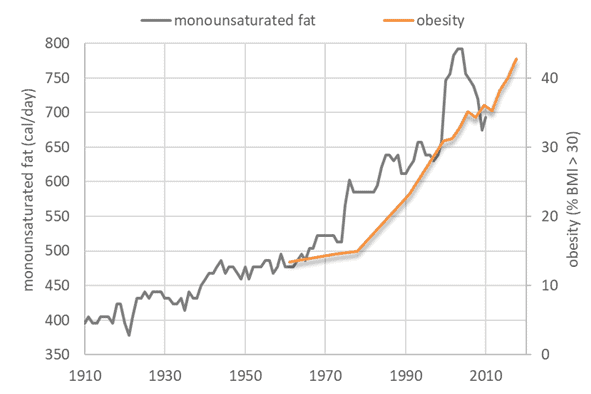

The chart below shows that the production of monounsaturated fats like olive and canola oils has been steadily trending upwards.

Meanwhile, our intake of polyunsaturated fats has also been trending upward. They are mostly from corn and soybean oils.

Over the past century, we’ve increased both our polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fat consumption by almost 300 to 400 calories per day, while saturated fat has increased by less than 100 calories per person per day.

While saturated and unsaturated fats behave slightly differently in your body, the headline issue is that the availability of fat has increased by eight hundred calories per person per day over the past century!

When we look at where this change has come from, we see that the increase in ‘salad and cooking oils’ coincides with our increase in body weight. Interestingly, our intake of animal-based added fat sources like butter, dairy, and lard has not changed significantly since 1970.

Given the massive increase in intake fuelling the obesity epidemic, I don’t think we can call polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats ‘good’ fats!

For more details, see Keto Lie #11: You Should ‘Eat Fat to Satiety’ to Lose Body Fat.

Myth #4: Fat Does Not Make You Fat.

With the recent reversal in thinking on cholesterol, some people have taken to believing that fat cannot make you fat because it does not raise insulin.

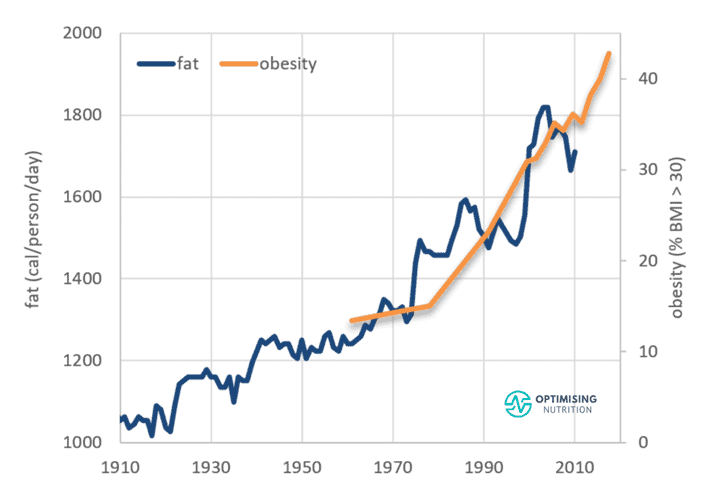

While it would be nice if we could enjoy as much fat as we wanted, the data doesn’t seem to support this belief. Instead, as shown in the chart below, obesity rates appear to have risen in line with fat, which has increased by around eight hundred calories per person per day over the past century!

Per our work on the food insulin index, we know that fat doesn’t raise insulin as much as carbohydrates in the short term. However, your pancreas must still release insulin to keep your body fat in storage while using up the energy coming in from your mouth.

While insulin plays a role in allowing your cells to use glucose when your blood sugars are elevated, we can also think of insulin as a brake that stops the liver from releasing stored energy into the bloodstream.

Your pancreas will raise your insulin levels to ensure you use up the energy from the food you’ve just eaten. Thus, your insulin will be higher if you have more body fat on board or you eat more regardless of the macro split.

At nine calories per gram, fat is the most energy-dense macronutrient. Unfortunately, very high-fat foods are also relatively low in essential micronutrients like amino acids, vitamins, and minerals that keep you feeling full. Thus, ‘eating fat to satiety’ might not be so satiating, and you may eat a lot more fat than you had anticipated.

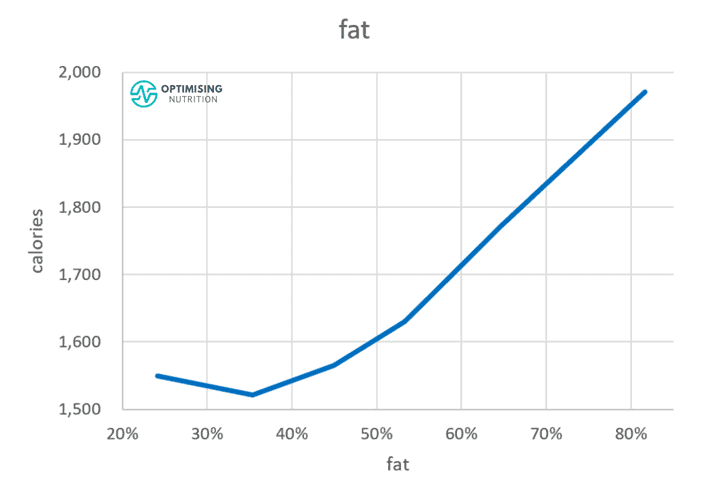

Our satiety analysis shows that, above around 40%, a higher fat intake aligns with a higher energy intake.

Per the First Law of Thermodynamics, energy is always conserved. If we relate this to nutrition, we either have to burn off the energy we’re consuming from food with activity or store it as fat. No matter what foods provide the bulk of your calories, you’ll store whatever you’re not burning off as body fat!

For more details, see

- Oxidative Priority: The Key to Unlocking Your Fat Stores

- Does Insulin Resistance Really Cause Obesity?

- The Carbohydrate–Insulin Hypothesis vs the Personal Fat Threshold Theory of Obesity,

- Keto Lie #5: Fat is a ‘Free Food’ Because it Doesn’t Elicit an Insulin Response and

- What Does Insulin Do in Your Body?

Myth #5: Only Carbs Make You Fat.

This belief is based on the idea that carbs raise insulin more than other macronutrients.

In people with diabetes, we have noted that injecting insulin can drive excess fat storage. If you recall, insulin is the brake to our liver that keeps us from using stored energy for fuel. By extension, some people have concluded that we will store more fat if we get more of our energy from carbs because they increase insulin more over the short term.

But how does this stack up with the data?

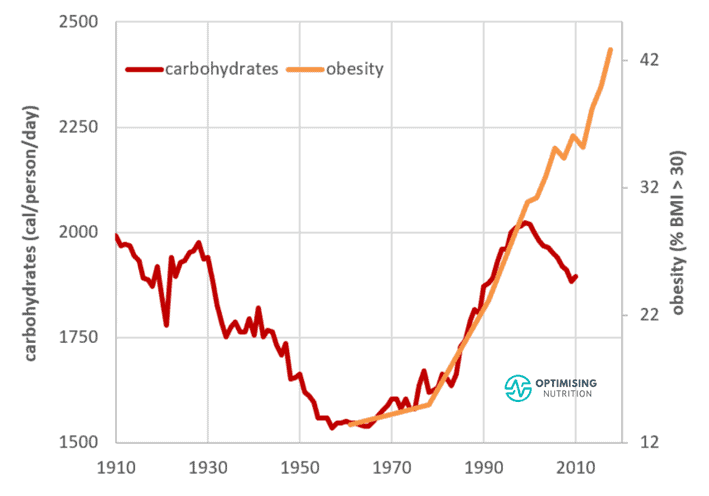

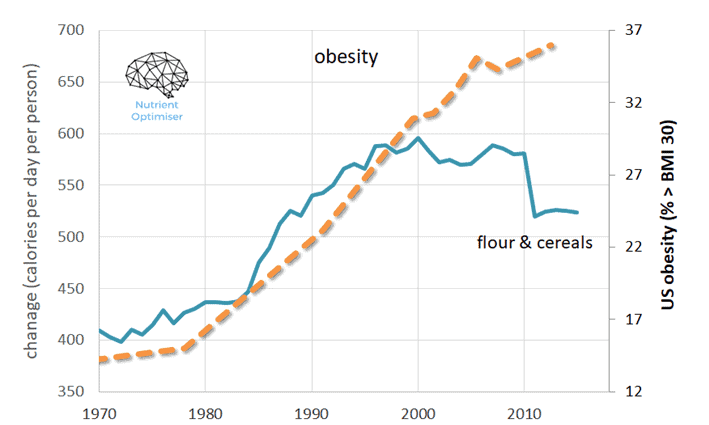

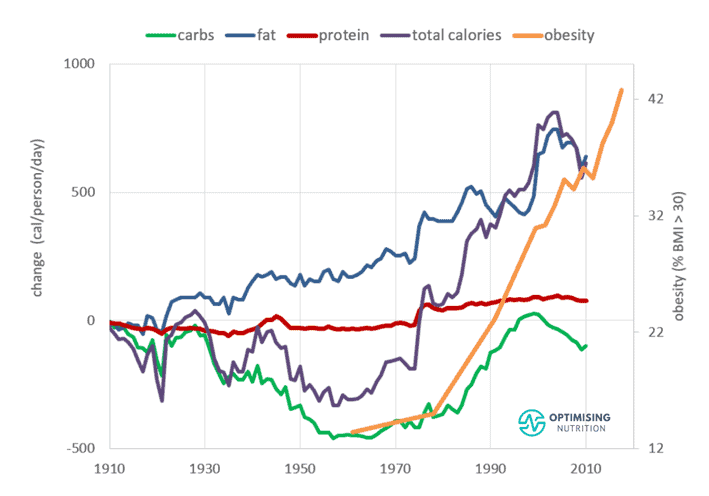

As the chart below shows:

- Carbohydrate production decreased in the United States from 1910 until about 1960.

- Between 1960 and 2000, obesity rose in line with increased carbohydrate intake.

- However, from 2000, carbohydrate consumption dropped while obesity powered on (and still continues to).

When Dr Robert Atkins released his book Diet Revolution in the 80s, it looked like carbs were driving obesity. Perhaps the popularity of this low-carb movement contributed to the decline in wheat and flour interest throughout the 90s. But the food industry pivoted, and the obesity epidemic has prevailed. As we will see below, the advent of artificial sweeteners enabled processed food manufacturers to create flavourful concoctions from seed oils without as much reliance on flour and sugar.

This divergence in the trend of obesity and carbohydrate production and consumption should cause a healthy level of scepticism around the idea that carbs are the primary thing that makes us fat.

While there’s no need to eat more refined carbohydrates than you need to, especially if your blood sugars are already dysregulated, it doesn’t appear that carbohydrates are the only smoking gun of the obesity epidemic.

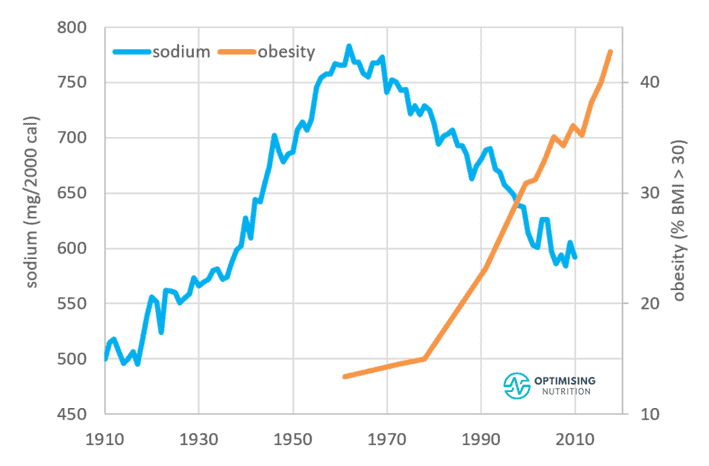

Myth #6: Salt Is Bad for You.

Too much sodium from salt has been known to increase blood pressure. Salt is a common ingredient in processed junk food that drives us to eat more of it. But despite low-salt DASH diet and nutrition guidelines, the obesity and hypertension epidemics have powered on.

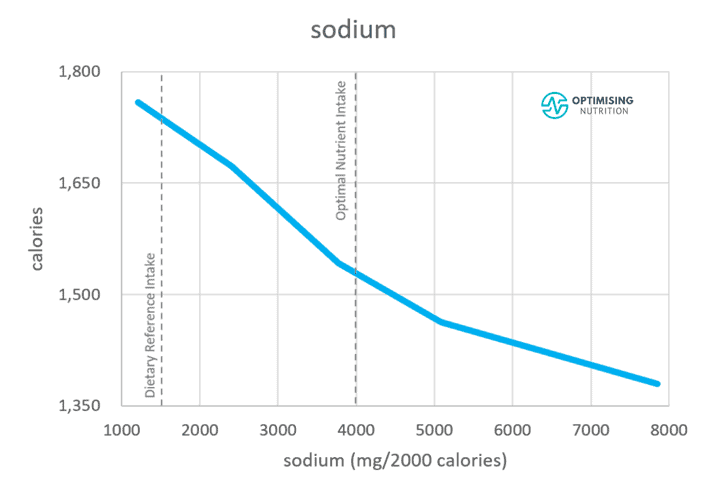

Per our satiety analysis, sodium is vital for taming our appetite and feeling satisfied. Thus, lowering our sodium intake may have worsened the obesity epidemic by driving us to get the salt our bodies require and thus consume more calories.

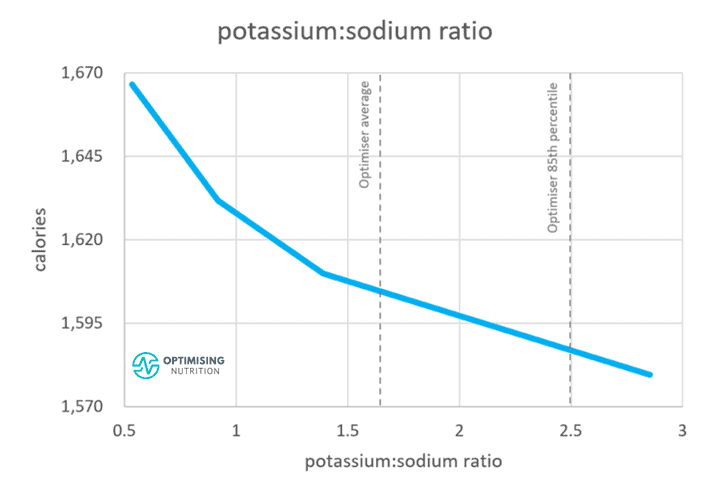

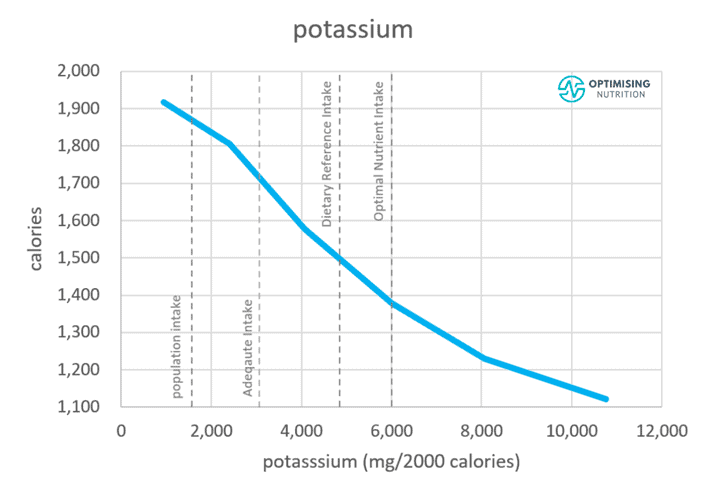

Sodium and potassium work in tandem; sodium balances the fluid outside the cells, whereas potassium balances the fluid inside. While many people believe it’s simply high sodium levels that underly hypertension, we’ve started to see that the problem is a lack of potassium in our diet to balance the salt. As shown in the chart below, people with higher potassium:sodium ratio tend to eat less.

In our Micros Masterclass, most people are already getting plenty of sodium by salting their food to taste and find they need to prioritise potassium before they worry about adding any more sodium.

For more on sodium, check out Sodium in Food: A Practical Guide and Micronutrient Balance Ratios: Do They Matter and How Can I Manage Them?

Myth #7: Calories Don’t Count.

Counting calories sucks, and it usually doesn’t work. However, people who believe ‘calories don’t count’ don’t exactly have it right, either!

Based on the First Law of Thermodynamics, we know that all energy is conserved. In other words, the calories you consume from food are either burned off from activity or stored as body fat. Calories count, but only if you can precisely measure both sides of the calories in vs calories out equation perfectly.

Mainstream diet trends like low-carb, keto, whole-food plant-based, paleo, keto, carnivore, Atkins, The South Beach Diet, or Whole30 that claim calories don’t count drive early success because they cut out the high-calorie combo of processed flours and added oils. This causes people to believe that the animal foods, carbs, or fat they eliminated caused their transformation—not the lowered calorie intake.

But the reality is that our obesity rates track reasonably closely with our increased calorie intake from hyper-palatable fat-and-carb combo foods.

Food production had dropped from 1910 to 1960, but calories and obesity have been on a similar upward trend since 1960.

I think it’s safe to say there is some relationship between calories and obesity!

For more, see Keto Lie #9: Calories Don’t Count.

Myth #8: Sugar Is Public Enemy #1.

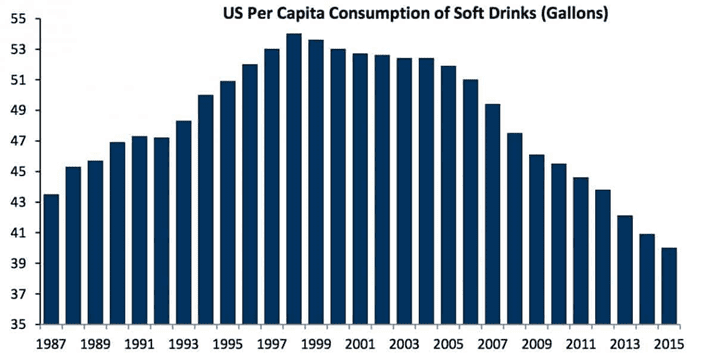

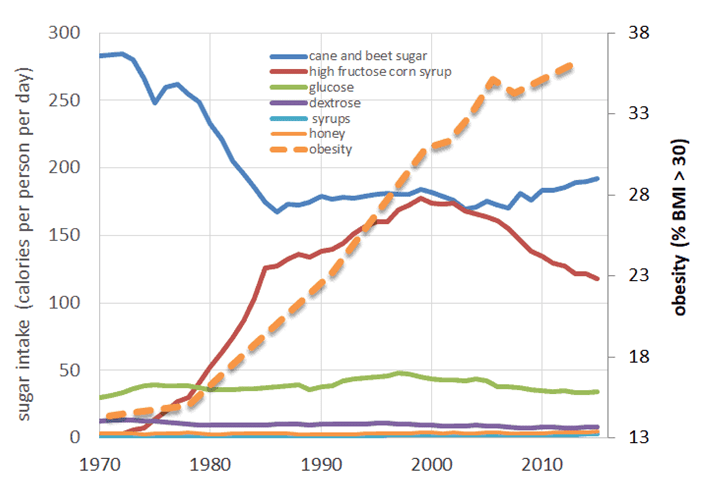

Other camps opine that added sugars are the most significant issue in our food system. However, added sugars and obesity diverged around 2000.

Data from the USDA shows that in 2015, Americans were using 15% less added sugar compared to when they peaked in 1999. After the advent of artificial sweeteners, food manufacturers no longer needed to rely on High Fructose Corn Syrup.

Between 1970 and 1999, High Fructose Corn Syrup replaced unsubsidised cane and beet sugar in the food system. Because of corn and wheat subsidies, HFCS was cheap and abundant.

With the introduction of flavour technology and artificial sweeteners, food manufacturers could take cheap flour and industrial oils and make them look and taste like real food without added sugars. This allowed them to satisfy market demand in new and creative ways.

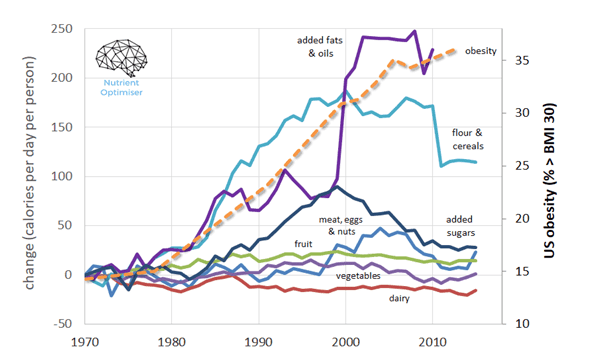

Since the 1970s, each American has consumed an average of 600 more calories per day than they used to. However, only a tiny portion of them come from added sugars. While many have been led to believe that these extra calories are from ‘meats, eggs, and nuts’, most of this excess energy actually comes from ‘added fats and oils’ and ‘flours and cereals’.

While refined sugar is effectively empty calories and does not help metabolic syndrome, I don’t think the case argument that sugar is the primary driver of obesity is as strong as some claim it to be. There’s no need to fear naturally occurring sugar in otherwise nutrient-dense foods.

Myth #9: Red Meat and Eggs Are Bad for You.

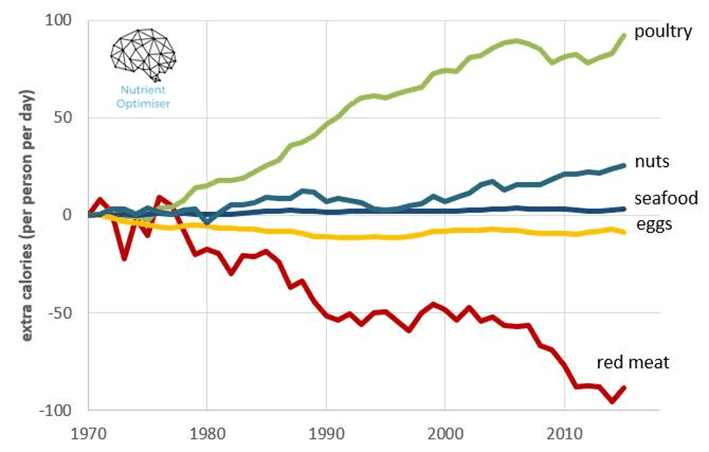

There has been a lot of fear instilled around saturated fat for reasons similar to cholesterol. This has caused many to believe that red meat causes cancer, which has pushed people to eat white meat instead.

The ‘red meat, eggs, and nuts’ category represents about 20% of total energy intake, which has decreased from 25% in 1970 (note: this is a percentage of total calories).

The overall increase in energy intake from meat, nuts, and eggs has only increased by 25 to 50 calories per day, which are insignificant compared to the increase from added fats and oils and flour and cereals.

The following chart shows the change in the foods that make up the ‘meat, eggs & nuts category’. Per the guidelines, we prioritised white meat, and our poultry consumption has increased almost as much as red meat has decreased. Our consumption of nuts has increased a little while our seafood intake has stagnated, and our egg intake has fallen.

Given our intake of red meat has declined throughout the growing obesity epidemic, it’s hard to support the claim that red meat, seafood, or eggs have any significant impact on the obesity epidemic.

Red meat, eggs, and seafood contain high amounts of essential micronutrients like amino acids, vitamins, minerals, and essential fatty acids. Per our satiety analysis, we know that eating enough of these nutrients is vital for feeling full.

Thus, we could argue that eating less of these foods has been detrimental to our waistlines and metabolic health as they’ve allowed us to eat more energy more quickly.

Myth #10: Macronutrient Percentages Matter.

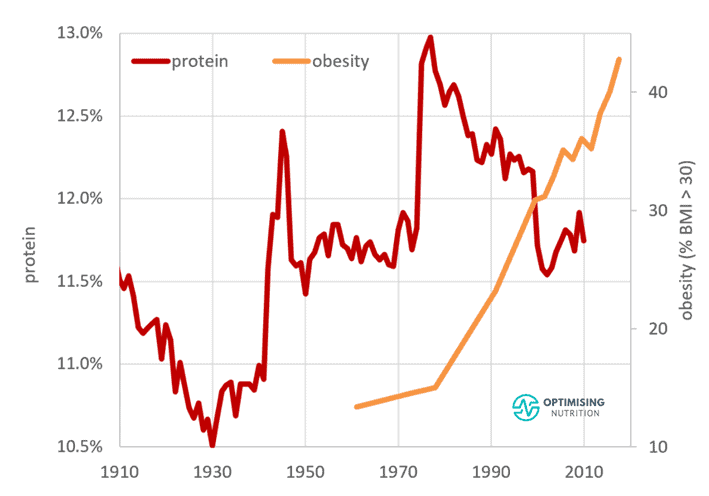

Our next chart shows the change in protein % over the last century, with an initial low of 10.5% coinciding with The Great Depression. From there, protein rose with affluence until the 1977 Dietary Goals for Americans encouraged people to reduce fats, especially saturated fat and cholesterol.

Since the release of these guidelines, people have responded by decreasing their protein intake, which aligns with the uptick in obesity rates. In other words, the lower someone’s protein consumption is, the more they want to eat to get the amino acids and other nutrients we require.

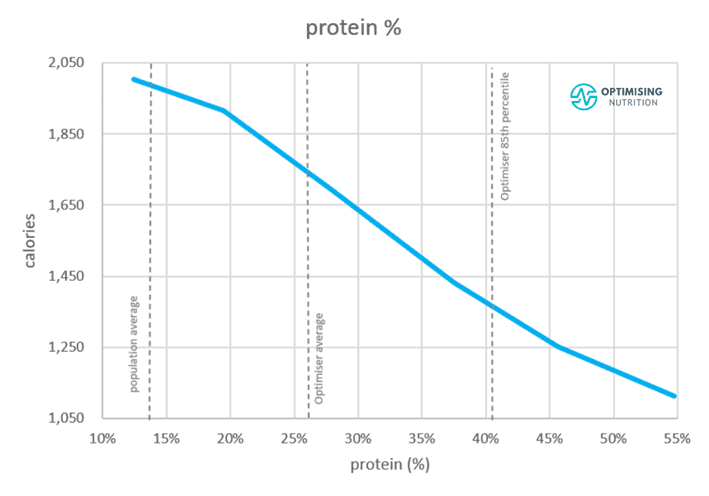

Our satiety analysis of data from Optimisers shows that people consuming less protein tend to eat more. So, while protein does contribute to your calorie intake, it seems you are likely to consume fewer calories overall if a more significant proportion of your total calories are from protein.

In response to the 1977 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, people reduced their percentage of total calories from fat and increased their carbs up until 1999. But since then, this trend has essentially reversed. When we look at long-term trends, we now tend to consume similar percentages of carbs and fat but with less protein.

The availability of carbohydrates and fat fluctuates largely in a natural setting, depending on the time of the year and our latitude. Fats and carbs are rarely available simultaneously unless for a period of growth (i.e., breastmilk for a growing infant, fruit and fats to fatten up for winter).

Both of these macronutrients affect the nervous system, and they elicit a strong dopamine response to get us to eat more, so we fill our fuel tanks. Our bodies are still relatively primal and want to ensure we get food whenever it’s plentiful, in case it isn’t available for some time. Thus, we tend to gravitate towards foods that combine them and stimulate both reward systems when fat-and-carb combo foods are available.

The image below was taken from Cian Foley’s Don’t Eat for Winter. It shows how the glycaemic index (G.I.) of foods varies with the seasons of the northern hemisphere. Essentially, Mother Nature provides us with more foods with a higher G.I. to prepare for the coming winter.

It’s as if the presence of foods with a similar proportion of fat and carbs tells your body winter is coming so you can raise your body fat setpoint. As we prepare for survival, our nervous system reinforces our ‘good behaviours’ by releasing a huge dopamine hit when consuming carbs and fat. Likewise, we get a synergistic dopamine hit when we consume foods that combine them.

These fat-and-carb combo foods are only possible with modern processed foods that rely heavily on added oils from soy and corn and processed flours from wheat and corn.

Rather than following seasonal variations, we can now eat the same gratifying food all year round. Unfortunately, this tells our bodies that winter is coming, and we need to store some extra fat.

The chart below summarises our satiety response to each of the macronutrients, showing:

- reducing either fat or carbs aligns with a similar reduction in overall calorie intake,

- increasing our protein %, by reducing energy from carbs and/or fat has the largest impact on our satiety.

So, in the end, it doesn’t matter whether you prefer to get your energy from carbs or fat, so long as you get the nutrients you require, particularly protein in your energy budget.

Bringing it All Together

Hopefully, you can see that many of the claims about what we should fear in food are not particularly useful. On the contrary, following them may lead us to be more confidently wrong.

Over the past six years of crunching the numbers on nutrition, I have become even more confident that all of the ‘bad’ things in our food sort themselves out when we prioritise getting enough of the essential nutrients we require within our daily energy budget. There is little left to worry about if you get enough nutrients without excess energy.

To wrap up, I want to share some new 3D charts that we have developed using our Optimiser data.

Carbs vs. Fat vs Protein

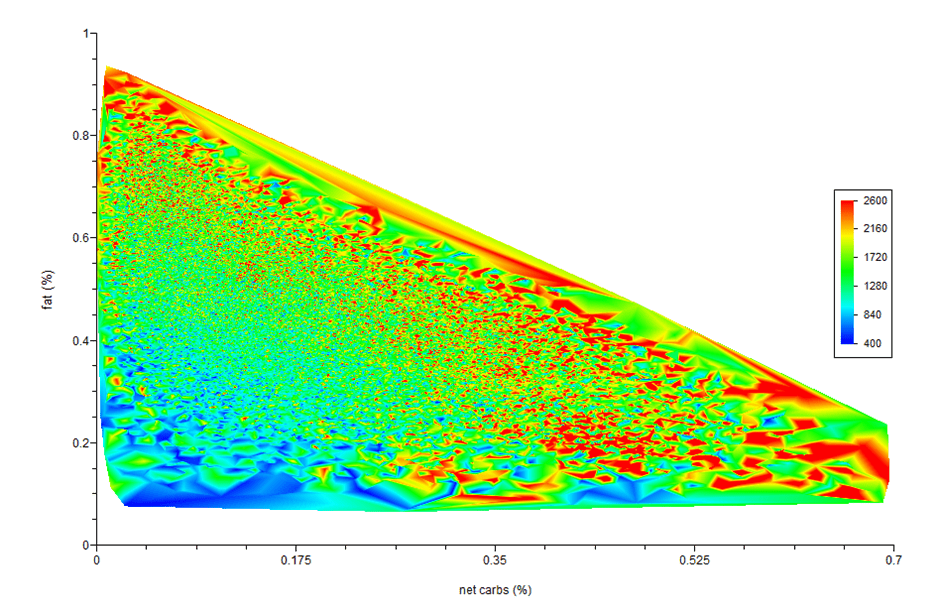

This first chart shows non-fibre carbs vs. fat, with the colour coding representing protein. The blue area represents days of data where Optimisers’ diets consist of mainly fat and carbs, while the red area is the high protein zone. In our Macros Masterclass, we guide Optimisers to identify where they sit on this landscape and guide them to adjust their macro targets to move towards their goal (e.g. a higher protein % for greater satiety and fat loss).

Carbs vs. Fat vs. Calories

This next chart shows carbs vs. fat vs. calories. The red areas correspond to the higher calorie intake, while the blue is the lowest calorie intake. Notice how the lower calorie intake aligns with the higher protein area in the chart above? As you move away from the low protein diagonal edge, you will automatically ensure that you are not getting excess fat, saturated fat, sugar, calories, monosaturated fat or polyunsaturated fat.

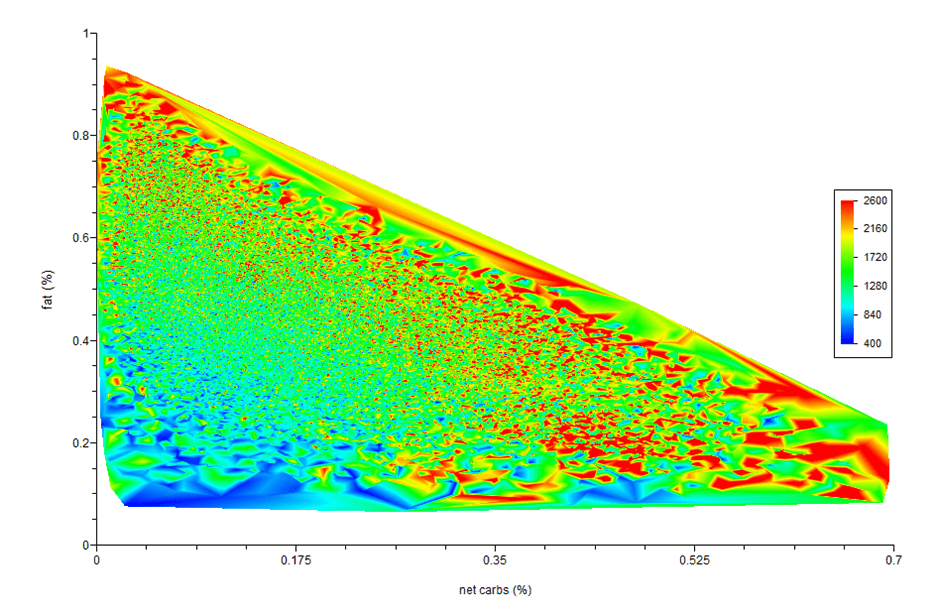

Carbs vs. Fat vs. Diet Quality

Finally, we have carbs vs. fat vs. diet quality. The blue areas represent very low nutrient density, while the red represents higher nutrient density. In our Micros Masterclass, we guide Optimisers to add new foods and meals that provide more of their priority nutrients while reducing energy from fat and carbs that they don’t really need to achieve a higher diet quality score.

It’s beautiful how this simple approach automatically leads people to realise they need to eliminate the foods that many would consider to be ‘bad’ for them in the pursuit of nutritional optimisation.

Legend Marty, if only everyone would absorb your info and put it to personal use, and the Food Companies change their ways. Youre a key player in the game mate. 🤘

Hello Marty, you have been systematically tunneling through this mountain of information which continually is being shaped by ignorance and beliefs, economic interests and lies, public policies and corruption, and, let’s not forget, the untiring work of scientists. Now there is some light at the end. Congratulations! I take off my hat.

Hi Marty,

Please do not perpetuate the common and widely disseminated error of the famous Keys Fat v Heart Disease graph by implying that it is connected to the the “Seven Countries Study”.

It has nothing to do with this study and was produced 5 years before it was started.

The graph was a slide produced for a lecture in 1953 and subsequently published as:

“Atherosclerosis: A problem in newer public health,” Journal of the Mount Sinai Hospital, 1953

You will also note that the graph only shows 6 countries not 7.

It should always be referred to as the “6 Countries Graph” and clearly labeled as such.

Totally agree, Mr. Lass. I don’t know why Mr. Kendall doesn’t change the description, especially because he is such a stickler for accuracy. If you are sloppy here, it makes one wonder what and where else the inaccuracies begin to mount.

I’m wondering why you kept HFCS and cane/beet sugar separate in your part about sugar. They are both roughly 50/50 glucose/fructose, are they not? Combine the two and it might paint a different picture.

They’re shown combined in the added sugar chart.

Hi Marty, nice overview of many pet theories. Just one place made me have a doubt really.when you said that the US has reduced carb production, and obesity rates are still going up. Don’t we live in a global economy these days? When a lot of our food is produced elsewhere, probably in 3Rd world countries? Bananas from Costa Rica, mangoes from Australia, nuts in Brazil etc etc?

Anything is possible, and no data is perfect, but it’s not the simplest explanation for what we see in the data.

Just watched it. Thanks for the heads up. I’m not sure which version of nutrient density he’s talking about that divides by fat. Lalonde’s version of ND is actually very very high in animal products. My version only focuses on the harder to find nutrients per calorie which gives a mix of plants and animals (I don’t think it matters whether you prefer more or less of one or the other). I think people get a bit excited about fat being an essential nutrient. You actually only need a few grams of omega 3. If you prioritise nutrients you will get plenty of fat and protein. All carbs are not evil just like all fat is not evil, however combining them into hyper-palatable fake foods tends to get us into trouble.

This draft post on nutrient density may add some clarity. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1KPmJvkqxoOLLLJ-r2Q8_-U3AJYuFJkFUjipCGbBDjm0/edit?usp=sharing

Hi Marty!

You’re churning through all of this data and gaining a lot of insight.

Please watch some of Dr. Greger’s videos about saturated fat, cholesterol, and the long-term effects on the heart. The Blue Zones, etc. Not saying veganism is the be-all-end-all by any means but severely limiting saturated fat intake and cholesterol intake will keep obesity at bay while ensuring the long-term health of the cardiovascular system. Thanks for the insight you’ve given so many people and keep up the great work!

As noted in the article there has been a reduction in saturated fat in percentage terms aligning with the obesity epidemic, so I think it’s hard to support an anti saturated fat view from this info or that it should be a primary focus. Dr Gregor is the medical director for the Humane Society and I feel his perspective on nutrition may be heavily influenced by this. https://optimisingnutrition.com/2017/07/25/vegan-vs-keto-for-diabetes-which-is-optimal/