Embark on a journey to understand insulin resistance and its profound impact. Amidst varied dietary advice, mastering the balance of macros—carbohydrates, proteins, and fats—is key to managing insulin resistance, fostering weight loss, and improving metabolic health.

This article sheds light on optimal macros for insulin resistance, helping you manage daily carb intake, comprehend insulin resistance symptoms, and steer towards effective weight loss and better metabolic health.

Your voyage towards debunking insulin resistance myths and embracing a healthier lifestyle begins here?.

- Background

- Symptoms of Insulin Resistance

- What Does Actually Insulin Do?

- Insulin and Type 1 Diabetes

- The Problem With Injected Insulin

- Can You Turn Off Your Pancreas?

- The Fatal Flaw in the Carbohydrate–Insulin Hypothesis

- Your Pancreas Does Not Produce More Insulin Than You Require

- How the Food You Eat Affects Your Insulin Levels

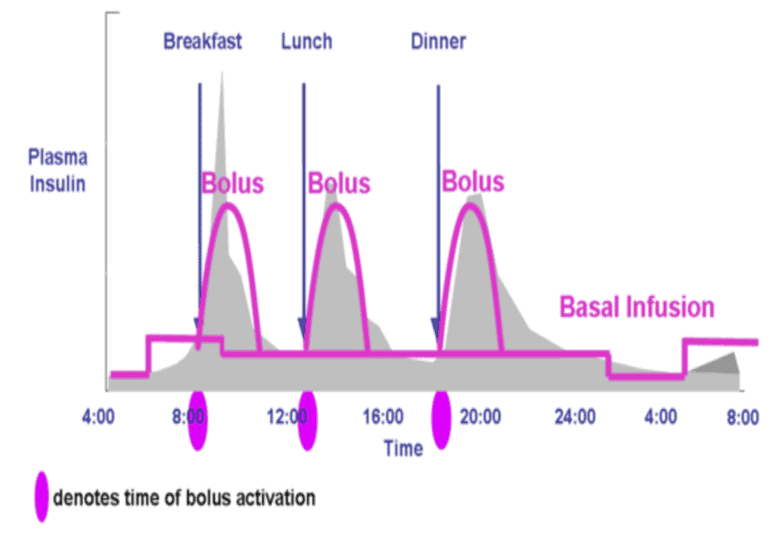

- Basal vs Bolus Insulin

- The Root Cause of Insulin Resistance Is Exceeding Your Personal Fat Threshold

- Can Insulin Resistance Be Completely Reversed?

- How Can I Reverse Insulin Resistance Quickly?

- How Long Does It Take to Completely Reverse Insulin Resistance?

- What Should Macros Be for Insulin Resistance?

- Is A Low-Carb Diet Good for Insulin Resistance?

- Reduction in Insulin Requirements on a High-Satiety, Nutrient-Dense Diet

- Insulin Change in Response to Weight Loss

- Nutrient-Dense, High-Satiety Recipes

- Summary

- More

Background

Let’s bust some myths and uncover the real deal about insulin resistance – it’s a journey that’s as complex as it is fascinating!

In the realm of low-carb and keto enthusiasts, there’s a common belief that reversing insulin resistance is as simple as waving goodbye to carbs and embracing fats while giving protein the cold shoulder.

But hold onto your nutritional compass because the truth is far more intricate. Swapping carbs for fat might help you tame one symptom of insulin resistance – those pesky post-meal blood glucose spikes. Yet, it may not be the golden ticket to address the root cause, which is energy overload, or give your metabolic health the makeover it deserves.

If you’re insulin resistant, carbohydrates may send your blood sugar on a rollercoaster ride in the short run. But here’s the twist:

- All foods have a backstage pass to trigger an insulin response.

- Insulin’s role is like a guardian, ushering energy into storage and keeping it there.

- The more body fat you carry, the higher your insulin levels tend to be.

So, it’s not as straightforward as

carbs -> insulin -> fat storage

Instead, it’s a captivating dance that goes like this: Low-satiety, nutrient-poor foods -> wild blood sugar swings -> insatiable cravings -> an energy intake frenzy -> fat storage -> a daily insulin rollercoaster.

Now, the real solution emerges:

High-satiety, nutrient-packed foods and meals -> tamed cravings and appetite -> controlled energy intake -> farewell to fat -> hello, healthy insulin levels!

In this article, prepare to unravel the puzzle. We’ll show you that it’s not just about dodging carbs and protein but about embracing nutrient-dense foods that keep you satisfied. This not only tames your appetite but also paves the way for weight loss without a growling stomach.

It’s a path to a better body composition and long-term metabolic health that you won’t want to miss!

BONUS: FREE Video Lecture “Making sense of the food insulin index”

Symptoms of Insulin Resistance

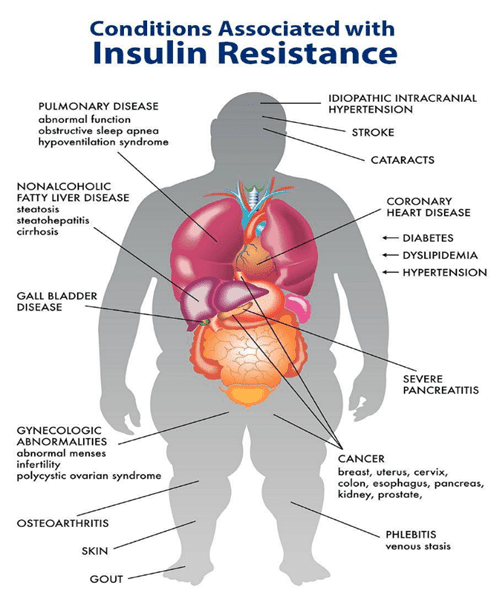

Hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance are associated with many modern health conditions, including:

- Type-2 Diabetes,

- Alzheimer’s,

- dementia,

- metabolic syndrome,

- heart disease,

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD),

- infertility,

- endometriosis,

- PCOS,

- obesity, and autoimmunity.

Yes, insulin gets the blame for a lot of things! But, as you will see, insulin is usually not the bad guy in the story.

It’s great to have healthy insulin levels! But there is still a lot of confusion about the best way to do it.

Much of the confusion stems from a misunderstanding of insulin’s primary role and what it does in your body.

As you will see below, insulin itself is not the fundamental problem. The root cause of all these issues is NOT insulin toxicity; it’s energy toxicity.

Insulin is not the root cause in this whodunit mystery. Your body simply responds with more insulin when you have more energy stored in your body.

Unfortunately, we often eat more than we need to because modern foods are designed with a perfect combination of fat and carbs, with minimal protein and nutrients.

But don’t worry. There’s good news. This article will show you how to adjust your macros to maximise satiety and reverse your insulin resistance.

But before we look at how to dial in your macros to reverse your insulin resistance, let’s look at the roles of insulin in your body.

What Does Actually Insulin Do?

Insulin plays several unique roles in the body:

- glucose uptake,

- anabolism, and

- anti-catabolism.

We usually only think of this anabolic hormone role of insulin, pushing energy into cells or helping to build and repair our muscles and organs.

However, it’s more helpful to view insulin as an anti-catabolic hormone that holds energy in storage and stops your body from breaking itself down.

My Insights from Living with Type 1 Diabetes

Over the past twenty years, I have helped my wife Monica, who has Type 1 Diabetes, actively manage her insulin and blood sugars. Additionally, in December 2021, our 16-year-old son was also diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes. So, insulin and blood sugar management are something I live and breathe every day.

Both my wife and son manage their blood sugars on a lower-carb diet. The most surprising insight from getting up close with Type 1 Diabetes, that I hadn’t heard from anyone else, is that their bolus insulin requirement (i.e. related to the food they eat) is only 20-30% of their total daily dose. Most of their daily insulin (70-80%) is delivered as basal insulin. Basal insulin is the anti-catabolic portion of insulin that stops the body from breaking down, whether they eat or not.

As you will see, this insight is critical to understanding how we can manage insulin resistance and optimise metabolic health.

Glucose Uptake

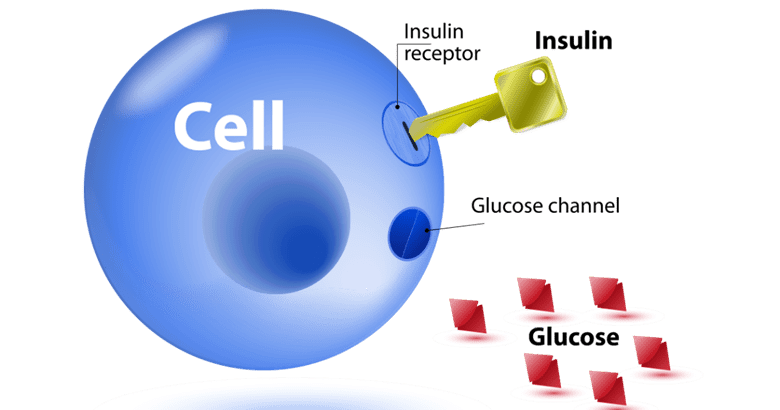

Insulin is a signalling hormone, made in your pancreas. When insulin is released, it signals to transporter proteins within the cell to rise to the surface. These transporter proteins are the portals that let glucose into the cell.

We often liken insulin to a key and to a lock that permits glucose into cells to be used for energy. This was the analogy my wife Monica was taught when she was diagnosed with Type-1 thirty years ago. It was also taught to my son when he was recently diagnosed.

Insulin indeed fulfils this function if necessary. If your blood sugar rises well above normal healthy levels, your pancreas will pump out some more insulin to slow the release of stored insulin and help the glucose enter your cells from your bloodstream.

However, we don’t always require insulin to use glucose. This is because glucose also enters your cells without insulin via non-insulin mediated glucose uptake (GLUT1 transporters). This occurs when you’re active or your cells are hungry for energy. When you have depleted the glucose in your cell, the glucose simply flows from your blood into your cells – it doesn’t need to be ‘pushed’ by insulin.

The 2011 study by Krakoff et al. titled Assessment of Non-insulin Mediated Glucose Uptake: Association with Body Fat and Glycemic Status showed that 83% of glucose uptake occurs through non-insulin mediated mechanisms like GLUT1 glucose transport.

Your body can clear 1.6 mg/kg of glucose per minute from your bloodstream without using any insulin. If you weigh 70 kg, that’s more than 160 g of glucose (or carbs) per day. So, if you’re on a lower-carb diet, all of the glucose you eat can be used by your body without any insulin!

Some degree of insulin pushing glucose into cells is common for people with insulin resistance and elevated blood sugars. While this is considered ‘normal’ today in a world awash with diabetes and obesity, it is really a crisis management situation that would have been rare in the past before we had constant access to food.

The amount of insulin released after a high-carb meal will be significant in someone with Type 2 Diabetes, however, their basal insulin levels will be even greater, especially if they hold a lot of fat in storage.

Insulin Is Anabolic

Insulin also helps you use food to build muscle, repair your vital organs, and store fat. Some bodybuilders even use massive amounts of insulin to help them grow. They also have to eat like their life depends on it to prevent their blood sugars from crashing (because it does). This is NOT recommended if you value your metabolic health!

Insulin Is Anti-Catabolic

While insulin does play a role in building and repairing your muscles, it really works to stop your muscles from breaking down. That is, the primary role of insulin is its anti-catabolic role.

‘… physiologic elevations in insulin promote net muscle protein anabolism primarily by inhibiting protein breakdown, rather than by stimulating protein synthesis.’

Gelfand and Barret, 1987

‘… it is demonstrated that in healthy humans in the postabsorptive state, insulin does not stimulate muscle protein synthesis and confirmed that insulin achieves muscle protein anabolism by inhibition of muscle protein breakdown.’

Nair et al., 2006

Insulin ensures your body doesn’t disintegrate with all your stored energy flowing into your bloodstream at once.

Imagine your body is like a giant water tank with a tap at the bottom that releases glucose and fat slowly into your bloodstream.

- Insulin is the signal that turns the tap (i.e. your liver) to allow just enough stored energy to flow into your bloodstream as required to fuel your day-to-day activities.

- Without insulin, the tap would remain open, and all the stored energy would flow into your bloodstream.

- The more energy you’re holding in storage, the more insulin is required to make sure the tap is turned off tightly to hold back the pressure.

For more details, see What Does Insulin Do in Your Body?

Insulin and Type 1 Diabetes

To better help us understand the role of insulin in our bodies, it’s useful to think of what happens to someone with uncontrolled Type-1 Diabetes, whose pancreas cannot produce enough insulin.

With no insulin, people with untreated Type-1 Diabetes release their stored energy (glycogen in the liver, body fat, muscle, and organs) into their bloodstream in an uncontrolled manner. Their blood glucose, ketones, and free fatty acids rise quickly, registering as high glucose in urine and ketones on the breath.

Without adequate insulin to turn off the tap, they basically disintegrate. Glucagon, the opposing hormone to insulin, has a catabolic effect. When it goes unbalanced, it causes an uncontrolled release of stored energy into the bloodstream. Thankfully, people with Type-1 Diabetes can quickly return to normal if they inject insulin, and their livers can hold back their stored energy.

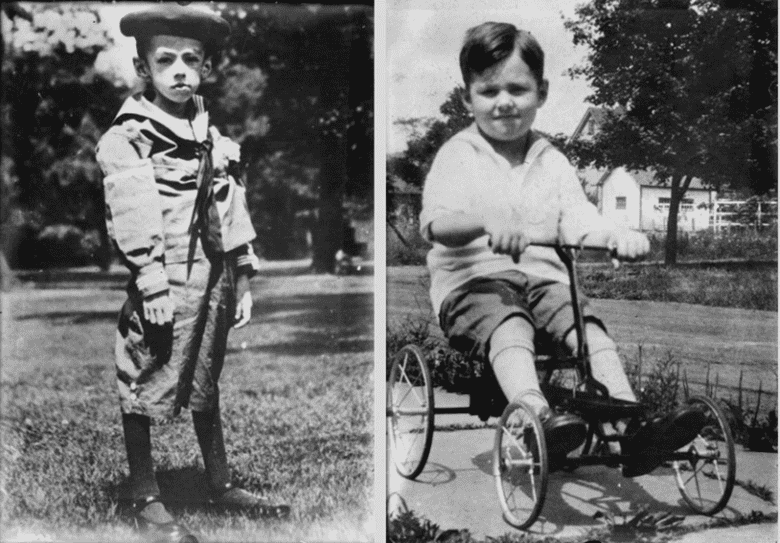

The before and after photo below shows the same child with Type-1 Diabetes before (left) and after (right) starting insulin therapy. Fortunately, it doesn’t take too long for the insulin to work and ensure that the food they eat is stored in their bodies again.

To bring things a bit closer to home, the photos below show my son Michael. In December 2021, we randomly tested his blood sugar, and it was 25.3 mmol/L (457 mg/dL)! Blood tests the next day revealed his HbA1c was 14.4%, and his fasting insulin was 3. He weighed 77 kg at the time.

The photo on the right shows him five months later after taking about 40 units per day of insulin at 90kg (13 kg heavier) with an HbA1c of 5.8% and dropping. The insulin per day stopped his body from breaking down. Along with some protein and weight training, the insulin also allowed him to rebuild his muscles and perform well in his first powerlifting competition.

The Problem With Injected Insulin

Insulin often gets a bad rap because it makes people put on weight rapidly. However, the problem is not the insulin but that it’s hard to match insulin doses perfectly to the foods they eat. This is especially true if they consume a processed, standard Western diet.

People injecting insulin often over-eat more than they otherwise would after their blood sugars drop too low because they have to compensate for injecting too much insulin. Once they refuel with highly processed fat-and-carb combo foods, they find their blood sugars are elevated, and they need to inject more insulin to bring them down again. This gives them a front-row seat on what we commonly refer to as the blood sugar-insulin roller coaster.

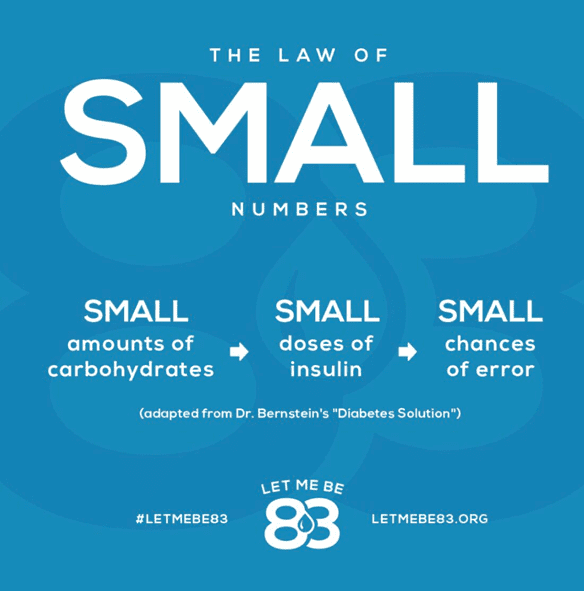

The good news is that reducing processed dietary carbs enables people who inject insulin to match their insulin requirements to their diet more accurately. Type 1 Diabetes guru Dr Richard K Bernstein calls this the law of small numbers and is key to achieving healthy, stable blood sugars and getting off the rollercoaster that can be brutal!

So, reducing carbohydrates until you achieve healthy, stable blood sugars (i.e. a rise of less than 1.6 mmol/L or 30 mg/dL after eating) is extremely helpful in managing hunger and appetite. But it’s only the first step to reversing insulin resistance.

Can You Turn Off Your Pancreas?

Although not a recommended weight-loss method, some people with Type-1 Diabetes employ a dangerous practice known as diabulimia, where they intentionally underdose insulin to lose weight. Yes, they lose weight, but they also see incredibly high glucose, ketones and free fatty acids in their blood. This is effectively a self-induced Diabetic Ketoacidosis.

While this may sound like a silly thing to do to yourself, this is effectively what many people without Type-1 Diabetes believe they’re doing when they reduce their dietary carbs to ‘switch off’ insulin production.

You can’t turn off your pancreas, no matter what you eat. And trust me, you don’t want to!

The Fatal Flaw in the Carbohydrate–Insulin Hypothesis

The central tenant of the Carbohydrate-Insulin Hypothesis of Obesity is that we can control our insulin by simply reducing our carbohydrate intake as if that’s the only thing that affects insulin.

Although many of us think we would like to turn off our insulin to lose weight, it doesn’t work that way if you’re part of the 99.5% of the population with a working pancreas and not injecting insulin.

In the absence of exogenous injected insulin, your pancreas produces just enough insulin to keep your energy locked away while new energy is coming in through your mouth.

Your Pancreas Does Not Produce More Insulin Than You Require

Like most things in nature, your pancreas is highly efficient and never produces more insulin than it absolutely needs to.

When you consume less energy, your insulin levels decrease, so stored energy can be released into circulation. As we will see, the key is to find a way to reliably eat less, so your body will use your stored energy for fuel.

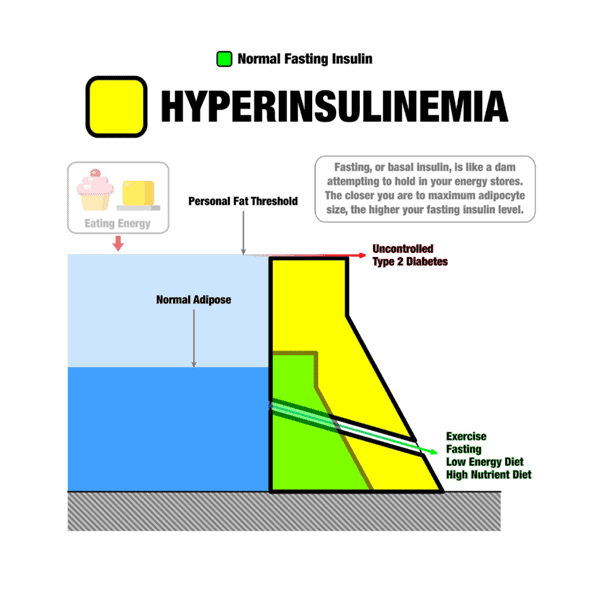

Optimising Nutrition advisor Dr Ted Naiman created his insulinographic below to show how insulin works like a dam wall to hold back stored energy (see this post for more details).

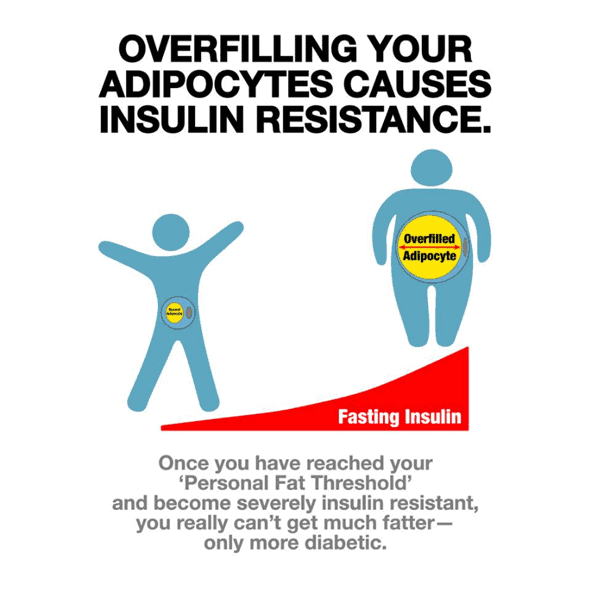

Once your fat cells fill up and exceed Your Personal Fat Threshold, any excess energy from your diet will overflow into your bloodstream as elevated blood glucose, ketones, and free fatty acids.

When you stop eating, your pancreas dials back its insulin secretion, and glucagon kicks in to release stored energy into your bloodstream.

Unless you have an insulinoma, a rare condition that causes the pancreas to oversecrete insulin, your pancreas will not produce more insulin than required to balance your stored body fat and dietary energy.

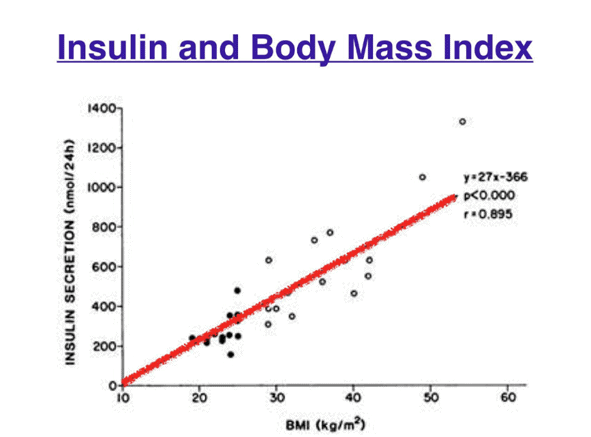

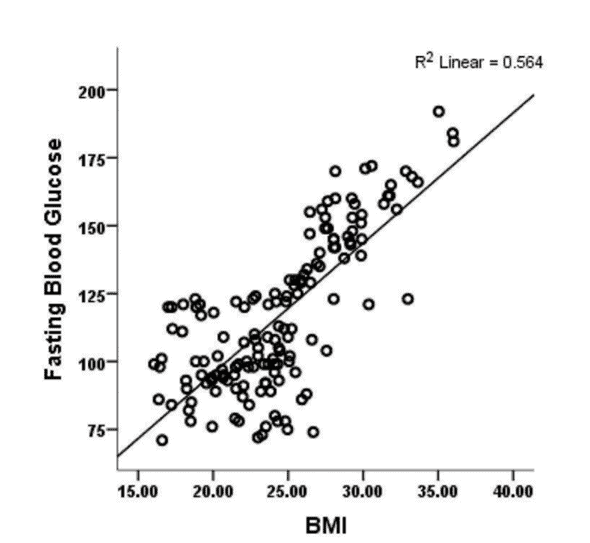

The chart below shows that your insulin levels throughout the day are highly correlated with your BMI, not your carbohydrate intake!

Reducing carbohydrates in your diet is helpful to stabilise insulin and blood glucose. However, simply switching carbs for fat is more or less symptom management.

Your total insulin levels and fasting insulin across the day will be elevated if you still have excess body fat. Whether you prefer a low-carb or high-carb diet, these markers will remain high until you offload the extra energy you have on board.

How the Food You Eat Affects Your Insulin Levels

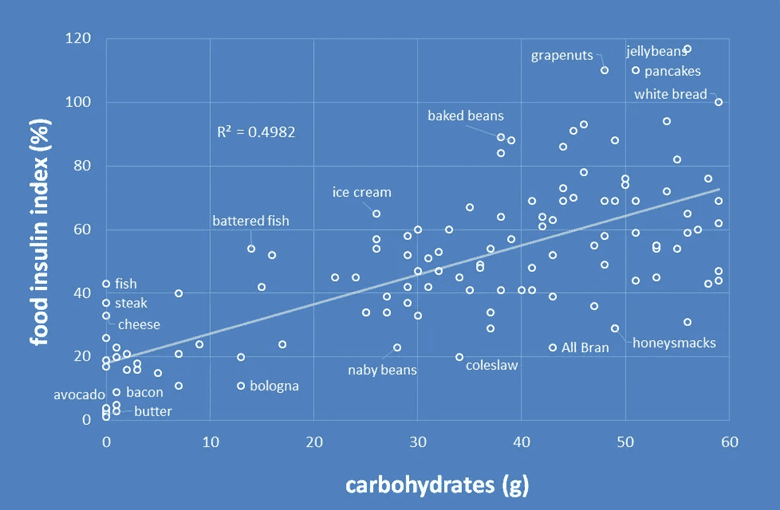

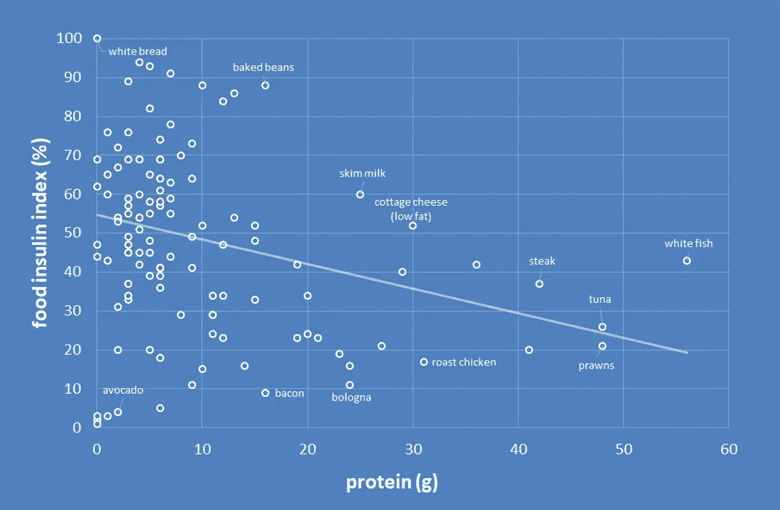

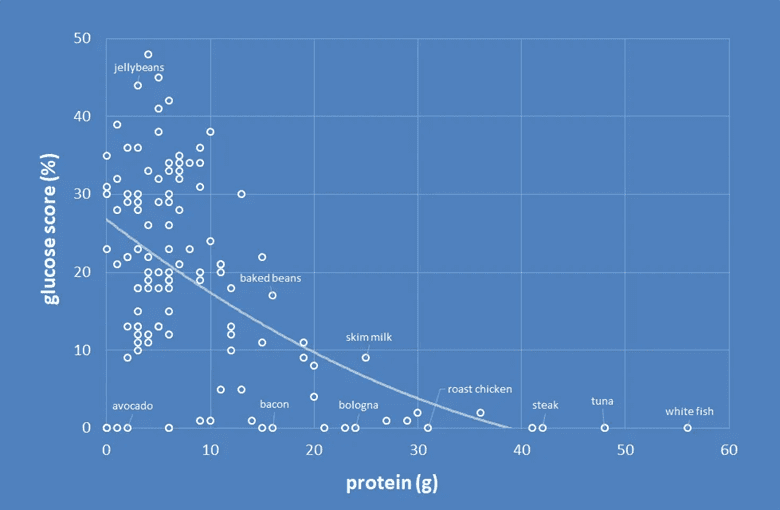

While it has its limitations, the food insulin index is an excellent tool for understanding your body’s short-term insulin response to food. As shown in the chart below, your insulin response in the short term is directly proportional to your carbohydrate intake.

However, we must remember that the food insulin index only looks at your response in the first two hours after a meal.

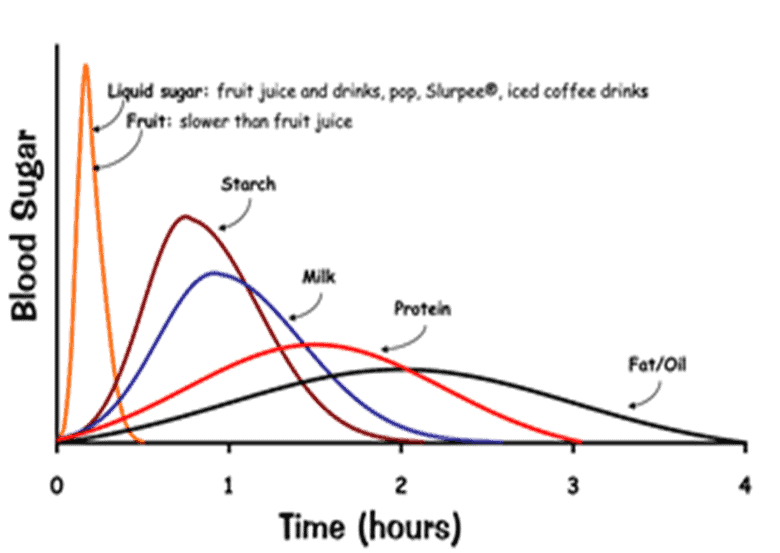

The chart below shows the change in insulin levels in the two hours immediately after eating different foods. While understanding the short-term insulin response is valuable for stabilising insulin and blood sugar and calculating short-term insulin dosages, we don’t understand much about how different foods affect our long-term insulin levels or those beyond the 120-minute mark.

While the insulin response to glucose rises and falls quickly, it’s worth noting in this chart that the insulin response to milk—a food that combines fat and carbs—continues beyond the two-hour mark.

Anecdotally, I’ve also learned a lot from watching the glucose response in my wife, my son and myself over the years. It’s been a fascinating learning journey to see which meals require more and less insulin! The highlights include:

- Glucose or pure carbs raise blood sugars quickly, but it doesn’t take long for some insulin to bring it back down.

- A low-carb meal with fat and protein takes eight to 12 hours to normalise blood sugars.

- Meanwhile, the occasional fat-and-carb combo meal can take more than a day to clear.

The key takeaway is that higher-fat foods definitely have an insulin response but over a longer time. Meals with protein and fat make it much easier to achieve healthy, stable blood sugar. However, ’it’s the carb+fat combo foods (with low protein) that have the largest response over the longest time, with the biggest area under the curve in terms of insulin and glucose—your body is in storage mode for much longer!

What Carbs Are Good for Insulin Resistance?

My analysis of the Food Insulin Index data shows that foods containing more of their carbohydrate as fibre tend to have a smaller glucose and insulin response.

High-glycemic, processed carbs raise our blood sugar and insulin levels quickly. Our bodies have a limited storage capacity for carbohydrates, so your pancreas responds by quickly shutting down its release of stored energy so you can use up the carbs you’re eating. But not long afterwards, your blood sugars drop back down.

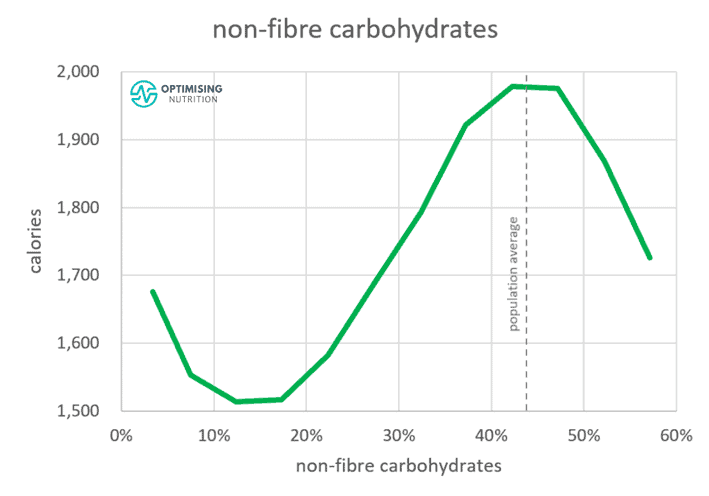

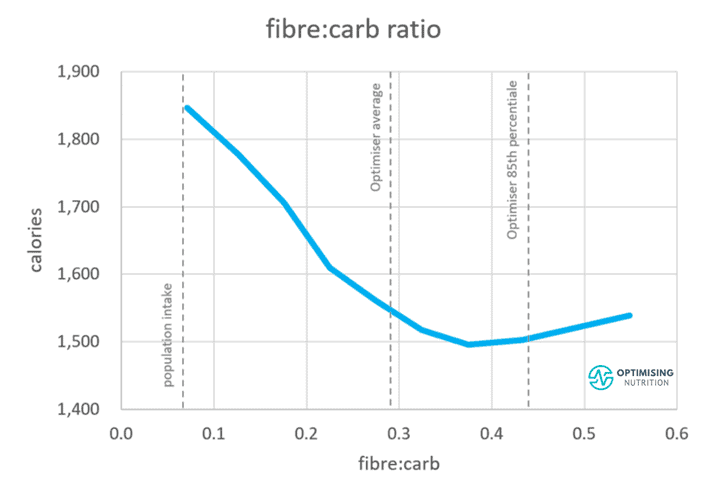

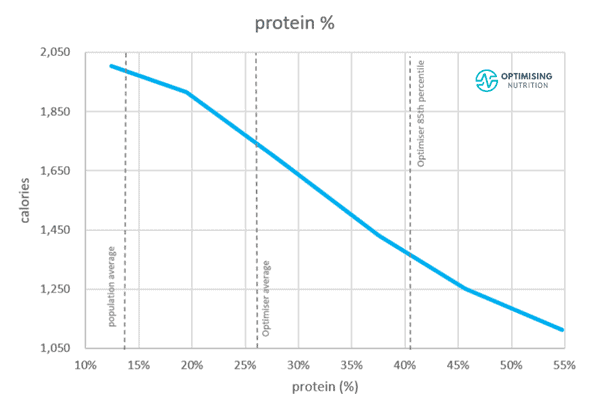

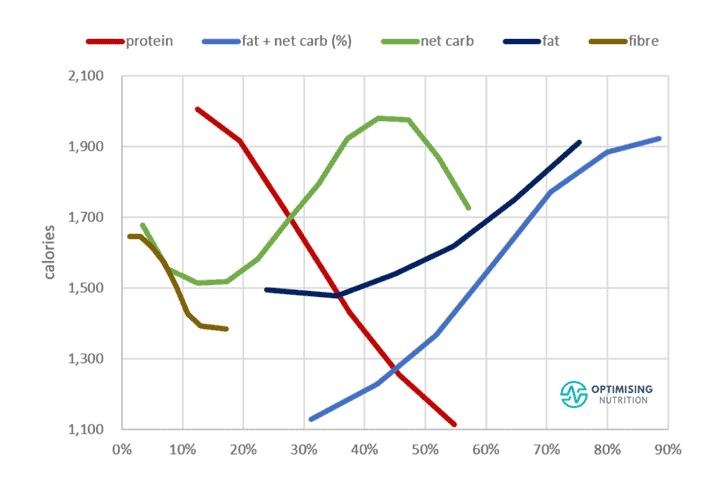

Our satiety analysis also shows that dialling back non-fibre carbohydrates to between 10-20% of calories aligns with the lowest energy intake. We eat the most when our diet consists of 40-50% non-fibre carbohydrates, with the rest of the energy coming from fat. Reducing your processed carbs intake will help stabilise blood sugars to healthy levels and help you feel fuller for longer with fewer calories.

But it may not be wise to jump from one extreme to another. Even if you’re trying to lose weight, you need to get some energy from your diet. So, in our Macros Masterclass, we guide Optimisers to progressively reduce their carbohydrate target until their blood sugars stabilise to healthy levels, with a rise of less than 1.6 mmol/L or 30 mg/dL after eating.

However, there is no additional benefit from reducing your carbohydrates below 10%. Fibrous non-starchy vegetables keep us feeling fuller than eating fat to satiety with zero carbs. Once your blood glucose levels are stable, you can progress to prioritising protein and dialling back your dietary fat.

Our satiety analysis also shows that we tend to eat a lot less when our carbohydrates contain more fibre. Thus, you will eat less if your carbohydrates are less processed and more fibrous — think non-starchy green veggies vs refined sugars and grains.

Does Protein Cause Insulin Resistance?

The relationship between protein and insulin resistance is less straightforward.

In the first few hours after eating, dietary protein requires about half as much insulin as carbohydrates. So, if you’re injecting insulin, it’s critical to understand that protein requires insulin over five hours or so.

When she has a steak for lunch, my wife will set an extended bolus over five hours to slowly drip out some insulin to keep her blood sugars stable. But, if you’re not injecting insulin, the fact that protein requires insulin and can convert to glucose is largely irrelevant. To read on how to account for protein in your insulin dose, check out Insulin Dosage Calculator for Type-1 Diabetes (Including Protein and Fibre).

However, while protein does require insulin, higher-protein foods tend to decrease our insulin response because they push out higher-carb foods from our diet.

The fact that protein elicits an insulin response is not necessarily a bad thing. As mentioned earlier, you need insulin to build and repair your muscles and vital organs. In addition, if you are eating fewer carbohydrates, your body can convert protein to glucose to meet its needs in a process known as gluconeogenesis.

Foods and meals with more protein tend to decrease blood glucose levels. Many people in our Data-Driven Fasting challenges use a high-protein snack as a hack to bring their blood sugars down when they feel hungry.

As shown in the chart below, higher protein food tends to raise blood glucose much less. For more on how protein affects insulin, check out Our Blood Glucose, Glucagon, and Insulin Response to Protein vs Carbs and Does Protein Raise Blood Sugar?

On another note, protein is the most satiating macronutrient, which can help you feel full and lose weight. In addition, as we will discuss later, offloading excess body weight tends to reduce your overall insulin requirements.

Finally, protein is the most thermogenic macronutrient. In other words, we burn the most energy (calories), converting it into usable fuel (ATP). This leaves us with fewer calories to store as fat.

Eventually, as we lose body fat and have less energy to hold in storage, our basal insulin requirements will fall.

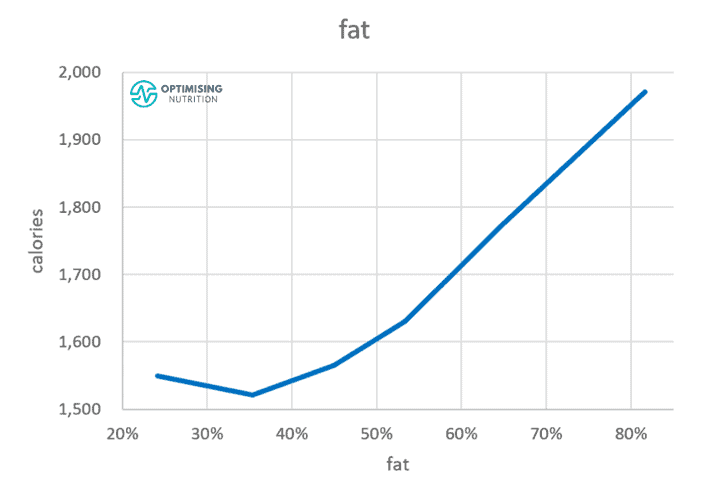

How Does Fat Affect Insulin?

Fat requires insulin, too. However, the insulin response to fat occurs over a more extended period.

Per oxidative priority, fat is last in line to be used for energy. Hence, your body doesn’t need to release insulin so abruptly in response to fat to halt the release of stored energy from your liver. We don’t have any good data on our long-term insulin response to fat. But it’s likely lower than carbs and protein because it is easily stored on your body.

To learn more about oxidative priority and how your body burns different fuels, check out Oxidative Priority, The Key to Unlocking Your Body Fat Stores.

The key thing to keep in mind with fat is that, similar to carbs, a higher percentage of energy from fat tends to align with a greater energy intake. So, if you want to lose fat from your body, you may need to reduce the fat in your diet.

Once your blood sugars are within the normal, healthy range, it doesn’t matter if you reduce your intake of fat or carbs, as both have a similar impact on satiety.

Basal vs Bolus Insulin

When thinking about insulin, most people unfortunately only consider their short-term response to the food they eat or their ‘bolus’ insulin. They fail to consider the basal insulin, which is required to keep their fat in storage over the longer term when food isn’t present.

To read more about the bolus and basal insulin, visit What Does Insulin Do In Your Body?

For someone eating a high-carb diet with Type-1 Diabetes, their basal insulin makes up around 30% of their daily insulin requirement. Nearly 70% of their insulin is bolus insulin, or insulin injected in response to their food.

For someone on a lower-carb diet, this ratio is typically reversed; their basal insulin makes up most of their insulin requirements.

The majority of the insulin produced by your pancreas is simply required to keep your fat in storage. While stabilising your blood sugars is important, the next step is NOT to flat-line them by simply eating fat and avoiding carbs and protein.

Instead, you need to decrease the amount of body fat you have stored to reduce your basal insulin levels. It’s important to remember that flat-line blood sugars does not equal metabolic health. Less variable blood sugars come from a healthy metabolism!

For more on this, see How to use a continuous glucose monitor for weight loss (and why your CGM could be making you fat).

The Root Cause of Insulin Resistance Is Exceeding Your Personal Fat Threshold

Because carbs raise insulin and blood glucose more over the short term, many people see diabetes as a disease of carbohydrate intolerance and insulin toxicity. But more recently, we’ve begun to view diabetes as being the result of energy toxicity and exceeding Your Personal Fat Threshold.

Once your fat stores become overfull and can no longer absorb extra energy, you exceed Your Personal Fat Threshold. At this point, ‘energy toxicity’ kicks in, and excess energy from your diet backs up in your system with nowhere to go. This registers as elevated blood glucose, ketones, and free fatty acids in your blood.

If you continue eating more than you need and past Your Personal Fat Threshold, your body stores the excess energy around vital organs like your liver, pancreas, heart and brain. This can result in conditions like pancreatitis, fatty pancreas, Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD), neurodegeneration, and heart disease.

Can Insulin Resistance Be Completely Reversed?

Rather than simply managing the symptom of high glucose by swapping carbs for fat, the real solution to reversing Type-2 Diabetes is to drain your glucose and fat stores.

By draining your glucose and fat stores, you will unload the extra energy you’ve stored on your body above Your Personal Fat Threshold. Over time, your body will begin regulating its energy usage once again, and your insulin sensitivity will return. Your insulin demands will fall, and your blood glucose response will be more controlled.

Studies by Professor Roy Taylor show that beta-cell function can be completely restored in many people once they lose a significant amount of weight. However, if someone has been suffering from Type 2 Diabetes for a very long time, they are less likely to be able to achieve complete restoration of full pancreatic function. Over time, the beta cells in the pancreas can become burnt out and are less likely to be restored.

In Data-Driven Fasting challenges, we focus on draining our fat and glucose reservoirs by using our blood glucose to guide when we need to eat.

How Can I Reverse Insulin Resistance Quickly?

To summarise, if you have diabetes and are investigating how to reverse insulin resistance and lose weight, your first logical step should be to reduce processed dietary carbs to the point where your blood glucose levels normalise to healthy levels.

The only practical way to reduce your basal insulin and reverse diabetes, insulin resistance, and all the diseases associated with metabolic syndrome is to find a way to create a sustained energy deficit while still getting the nutrients you need from food. This is more effective than the ‘keep calm and keto on’ and ‘eat fat to satiety’ mantras based on the mistaken belief that fat does not trigger an insulin response.

To do this, it’s critical to dial back your intake of carbs and fat while dialling up your protein and fibre. Protein is the most satiating macronutrient because it contains a lot of essential micronutrients like amino acids, vitamins, minerals, and essential fatty acids. It’s also the most thermogenic macronutrient, or the macronutrient we burn the most calories turning into usable fuel. Low-energy-dense fibrous carbs provide some of the harder-to-find micronutrients that animal foods lack.

By scaling back on carbs and fat and increasing your protein intake, you will be able to improve satiety and eat less without having to exert so much self-control.

However, while a very high protein % diet will be the most effective way to lose fat and reverse your insulin resistance rapidly, the process also needs to be sustainable. For more details on the downsides of rapid weight loss, check out the article Secrets of the Nutrient-Dense Protein Sparing Modified Fast.

How Long Does It Take to Completely Reverse Insulin Resistance?

Depending on your starting weight, Your Personal Fat Threshold, and how aggressive you are, the time it will take you to get from start to finish will also vary. However, many participants in our Macros Masterclass and Data-Driven Fasting challenges see significant changes in their weight, body fat percentage, and waking blood glucose in just the four-week duration of the programs. Consistency and diligence are key!

What Should Macros Be for Insulin Resistance?

Contrary to what trendy insulin resistance nutritionists might tell you, there is no universal macro ratio for insulin resistance.

While eating more protein and fibre with fewer carbs and fat is essential, everyone has different demands based on their activity level, metabolic rate, muscle mass, and a long list of other factors. Thus, there is no perfect ‘insulin resistance macros ratio’ or ratio breakdown of macronutrients that’s universal for everyone with insulin resistance. Besides, jumping from a diet of X amount of protein directly to Y amount can be a shock to the system (and the mind) and push someone to tap out quickly.

The chart below shows a comparison of each macronutrient vs calorie intake from the analysis of our data from Optimisers. Progressively dialling back both fat and refined carbohydrates while prioritising protein and fibre leads to greater satiety and more rapid weight loss. However, the ideal macros for you will depend on where you’re starting from.

In our four-week Macros Masterclass, we walk our Optimisers through the process of tracking their current diet and slowly moving towards one with an improved protein percentage until they find the minimum effective dose or the most minimal amount of change that still moves them towards their goals.

Is A Low-Carb Diet Good for Insulin Resistance?

A low-carb diet can improve blood sugar control. However, it’s critical to distinguish between high-fat and low-carb when investigating a diet’s nutrient density and how it will affect satiety and the energy you have onboard.

At nine calories per gram, fat is the most energy-dense macronutrient. In comparison, carbs and protein come in at four calories per gram. Most fats, in their oil form, contain little in terms of micronutrients or vitamins and minerals. Thus, they are not as satiating and can be easier to over-eat.

If you continue overeating energy from fat, you can still worsen insulin resistance despite eating a ‘low-carb’ diet. Thus, it’s important to prioritise protein so you are more satiated.

Reduction in Insulin Requirements on a High-Satiety, Nutrient-Dense Diet

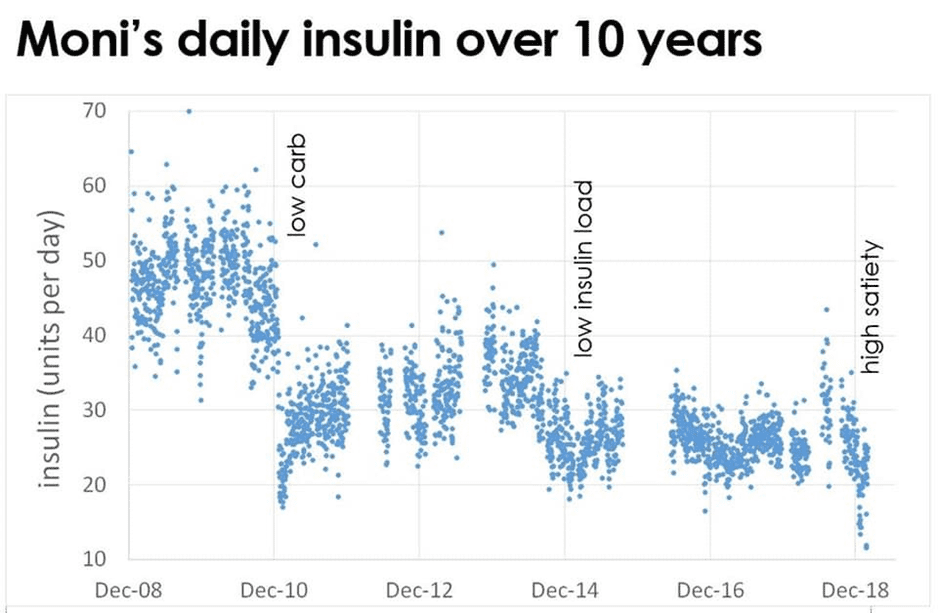

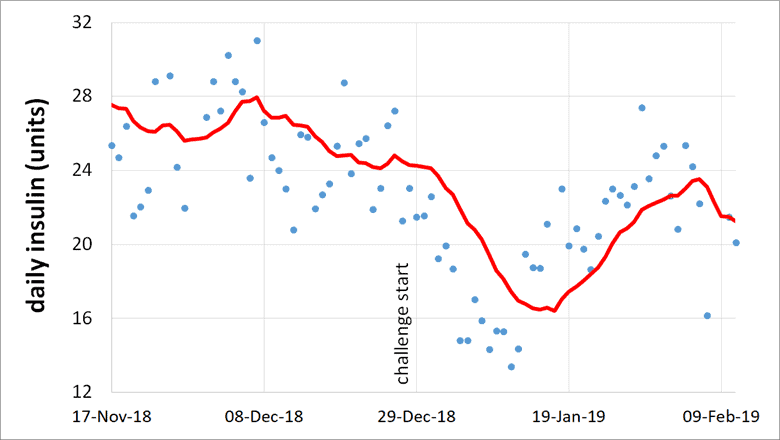

To demonstrate how this works in practice, the chart below shows my wife Monica’s total daily insulin doses (i.e., bolus and basal insulin) over the last ten years since she’s had her insulin pump.

For reference, this is a photo of us around the time she got her pump.

From the start of 2011, you can see the step-change in her insulin requirements when we switched to a low-carb paleo-style diet. This was a game-changer for controlling her blood sugar and insulin dosing, and it enabled her to lose a significant amount of weight.

Processed, hyper-palatable foods not only make accurate insulin dosing tricky, but they also make it hard not to overeat. Before we made the switch, she was constantly overcorrecting with insulin, making her eat more to get out of lows.

Towards the end of 2014, I started unpacking the insulin load concept and developed some of our early optimised food lists to stabilise her insulin requirements. With these introductions, we saw further improvements.

Fast forward to the start of 2019, when we had the Nutrient Optimiser Challenge, a prototype of the Macros Masterclass. Here, Moni focused on high-satiety, nutrient-dense meals and her daily insulin requirements were the lowest they’d been since being diagnosed with Type-1 Diabetes three decades ago! Her daily insulin requirements had dropped from around sixty units per day to 15 units per day while she was rapidly losing weight.

Monica was the only person in the challenge with Type-1 Diabetes. However, other people with Type-2 Diabetes saw an average reduction in their blood sugars from 7.4 mmol/L to 6.1 mmol/L (134 mg/dL to 110 mg/dL) as they focused on prioritising nutrient-dense foods and meals that were designed to optimise satiety.

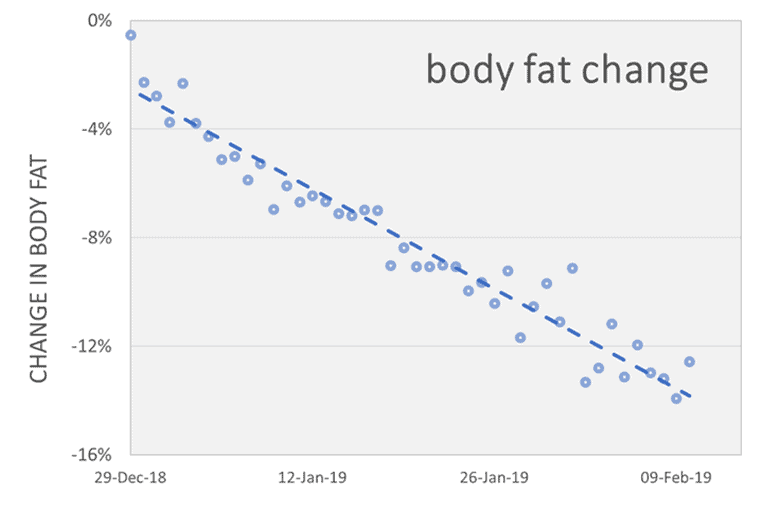

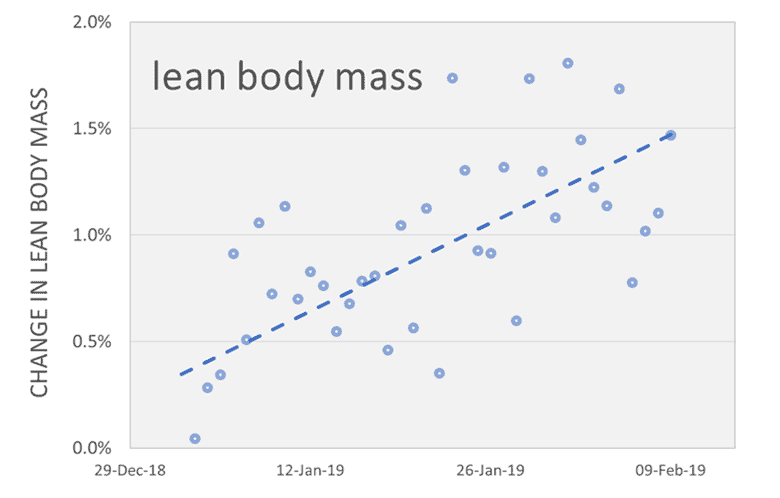

Regardless of whether other participants thought they were insulin-resistant or sensitive, a significant amount of weight was lost across the board.

Participants also gained lean muscle mass while losing fat.

Insulin Change in Response to Weight Loss

Hopefully, you can see that we need to focus more on total daily insulin requirements than short-term changes in insulin after meals. Measuring insulin in someone with Type-1 Diabetes is really the only way to see how this works in practice.

The chart below shows Monica’s insulin dose in the period leading up to and during the challenge. As soon as she started eating protein-rich, high-satiety meals, her insulin requirements plummeted to the lowest they’ve been in 30 years!

During those six weeks of the challenge, Monica lost 7.5 kg or 10.7% of her starting body weight. The photos below show Monica and me before and after the six weeks.

Monica’s insulin demand dropped by nearly 50% once she focused on our nutrient-dense, high-satiety meal plans. The main difference between her previous approach and when she was enrolled in the challenge was a significant reduction in her intake of nuts, cheese, and cream. While these are low-carb and keto staples that many people use to help maintain stable blood sugars, they are relatively high in calories.

Although a high-fat diet can stabilise insulin demands, high-fat foods still affect insulin requirements, especially when eaten to excess!

While low-carb foods like nuts, cheese, and cream can be a good way for people with diabetes to get energy, they still trigger a long-term insulin response. They also don’t provide as many micronutrients or amino acids, vitamins, and minerals, to optimise satiety. Focusing on more nutrient-dense foods improves satiety and reduces overall demand throughout the day—not just in response to one meal!

While you can count calories to try and eat less, most people don’t find long-term calorie restriction sustainable. In addition, it’s challenging to manage diet quantity until you modify your diet quality.

Our extensive satiety analysis has shown that decreasing how much you eat becomes more manageable when you prioritise foods and meals that maximise nutrient density and improve satiety. Giving your body the raw ingredients it needs empowers you to feel fuller and minimise cravings. Aside from macronutrients like protein, our analysis shows that micronutrients also play a crucial role in satiety.

Nutrient-Dense, High-Satiety Recipes

There is no one-size-fits-all insulin resistance meal plan to fit everyone’s goals and preferences. While improving nutrient density and diet quality sounds great, how do you start?

Many people have asked for more detail about the recipes our Optimisers use in our Macros and Micros Masterclasses to lose weight. This made us realise that our recipes are really the ideal place for people to start on their journey towards Nutritional Optimisation.

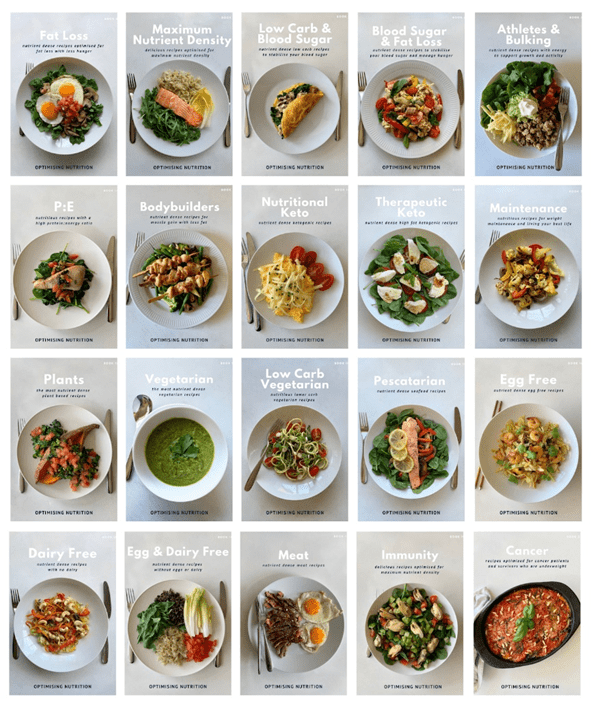

If we’re going to encourage people to eat healthier meals, we have to give them the tools to do so. In order to accomplish this, we spent six months working to refine our recipes for different goals, and we ended up creating 28 NutriBooster recipe books!

Summary

- High insulin and insulin resistance are associated with numerous health conditions and complications.

- While insulin is usually thought of as an anabolic hormone, we understand it better if we view it as an anti-catabolic hormone that stops the flow of stored energy from the liver.

- Carbs are not the only factor influencing our insulin levels and blood glucose control. Whether or not you are ‘energy toxic’ and have exceeded Your Personal Fat Threshold influences your insulin response the most.

- While carbs spike blood sugar and stimulate insulin the most in the short term, all food provokes an insulin response in the fullness of time.

- Although carbs and protein elicit an insulin response, it does not mean we should avoid them entirely. Instead, we must dial up our protein and fibre while dialling back on our carbs and fat as we do in our Macros Masterclass. This will improve our nutrient density and allow us to feel satiated so we can restrict calories and reduce the energy we have onboard.

- A low-carb diet can help control blood glucose and manage insulin resistance. However, if this drives us to eat more fat than we need, we contribute to the root cause of insulin resistance (energy toxicity).

The nutrient-dense, high-satiety recipes in our 22 recipe books are a great way to start changing your diet, managing your insulin and blood sugar levels, and moving towards Nutritional Optimisation.

Reducing processed carbohydrates will help to lower your blood glucose and insulin levels over the short term. But if you want to reduce your basal insulin and avoid the complications of hyperinsulinemia and metabolic syndrome, you need to focus on optimising your body composition. This entails losing body fat and (or) gaining muscle.

So, it’s not:

carbs -> insulin -> fat storage

But rather:

low-satiety, nutrient-poor foods -> erratic blood sugars -> increased cravings -> increased energy intake -> fat storage -> increased daily insulin

So, the solution is:

high-satiety, nutrient-dense foods and meals -> decreased cravings and appetite -> decreased energy intake -> fat loss -> healthy insulin levels

More

- What Is Insulin Resistance (and How to Reverse It)?

- Does Protein Spike Insulin (and Does It Matter)?

- Waking Up with High Blood Sugar? It Might Be the Dawn Phenomenon.

- Making Sense of the Food Insulin Index

- Personal Fat Threshold Model of Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, and Obesity

- Does Insulin Resistance Cause Weight Gain?

- How to Reverse Type-2 Diabetes and Optimise Your Blood Sugar

- Which NutriBooster Recipe Book Is Right for Me?

- Data-Driven Fasting: How to Lose Weight and Reverse Type-2 Diabetes Without Tracking Food

Hey Marty

The blood sugar thing is still a mystery thing for me. A friend of mine is taking Diabex, to supposedly make insulin use the glucose more efficiently. I’m thinking she is really Type 2 but won’t admit it. Any thoughts?

Diabex appeards to be metformin which is a popular drug for people with diabetes. Generally seems to have positive benefits (with some minor draw backs). Fundamentally, as detailed in this article, diabetes is a condition of energy toxicity (too much food, too much body fat) that tends to come back into line if you can focus on less processed high satiety nutrient dense foods.

Hey Marty,

My case is the perfect example to back up everything you and Ted Naiman are putting out there. I have a physiological change because of childhood radiation therapy simulating an acquired lipodystrophy in my subcutaneous adipocytes. I’ve been part of studies where I allowed harvesting of these cells for analysis at Rockefeller University in NY. (Search for total body radiation and metabolic syndrome /adipocytes/ adipokines in pubmed for more info). I am very lean (on the surface and simply cannot gain subcutaneous fat, BUT, I can easily store visceral fat. This has led to fasting triglycerides of 300 at age 12, and anywhere from 600 to 1000 during my 30’s. It also has caused the associated hyperinsulinemia, multiple cancers, gout, an early heart attack and Pre-diabetic glucose levels for over 20 years. There is a perfect linear relationship between my total fat load (measured by dexa) and my insulin levels, glucose levels. My LDL P is also affected by the triglycerides as any excess leads to overproduction of oversized VLDL, subsequent small dense remnants, despite very low LDL -direct readings.

The bottom line is that both keto and low carb approaches have not corrected any of the hyperinsulinemia, hyperhomocystemia, hyper triglyceride levels, and a few other side effects.

Thanks for sharing Rob!

question about some of the nutrient levels…specifically vit d, B1 and Zinc. None of these plans reach this, even with 2000 calories which is too much for someone of my size. What is the recommendation on this? Supplement?

These charts are based on the % of the Optimal Nutrient Ontak Levels (note DRIs). So they are much more conservative. Check out this post for more details. https://optimisingnutrition.com/the-optimal-nutrient-intake-oni/

We try to get the nutrients they need from food. Most people can easily reach the DRI without supps. Check out our 7 Day Free Food Discovery Challenge if you want to find out what nutrients your diet is missing and what foods will fill them in (see https://app.nutrientoptimiser.com/optin1587482063307). .

Type 1 diabetic loves weight training here. I’d like to know what your son was eating and doing to hai 13kg of muscle in 3 months. Amazing A1c as well!!

Before we realised he was T1D he had a lot of carb cravings – presumably because he wasn’t able to use the glucose – and eating a LOT. Interestingly, his appetite settled down once we got him on insulin. After we got him on insulin he managed to lock into a lower-carb protein focussed diet (lots of fatty beef patties, steak, protein powder etc). Snacks are often low carb/keto to get energy in. There’s definitely still some carby snacks to try to control the BGs – he’s still learning to fuel for events. Now fueling with a fatty protein shake tends to work best with a little bit of glucose from somewhere if he’s going low. I can’t want to get him on a closed loop pump system to really dial in his control! The insulin basically enabled him to put back on the weight that he would have had on if it wasn’t for the insulin insufficiency. Hoep that helps.

I have higher than optimal fasting glucose (100 to 120) in the morning, but my A1C is 4.7% (low). I’m quite thin at a BMI of 25 and I’m 46 year old male. Why is my glucose always high in the morning? I’ve heard of the dawn effect but it seems like I should be working on getting this lower. I’m on a plant based whole food diet now with a bit of fish.

Your low A1C sounds like the BGs the rest of the day are pretty healthy! I wouldn’t stress too much if your body fat % and waist to height are also dialled into healthy levels. IF not, a little bit more weight loss might help the waking glucose. We tend to see a trend with low carbers having higher waking glucose and lower during the day and vice versa for people on a lower-fat diet. In the DDF Challenges we generally recommend people focus on protein in the AM when hungry if their BGs are elevated – this helps with satiety and dropping blood glucose sooner.

Wow, a lot of work went into that (thanks very much), and I haven’t followed the hyperlinks.

Minimize carbs, prioritize protein, and be mindful of adding fat (it will be stored).

Correct?

I eat mostly beef and eggs, but I do snack on strawberries. Cucumbers are also good.

thanks. that’s pretty much it. I would say prioritise protein and nutrients within your energy budget. and yes, any energy from fat not used will be stored. strawberries and cucumbers probably aren’t going to blow your energy budget. zero carb is not necessarily better than lower carb – you need some energy from somewhere.

Thanks for the very detailed explanation!

I think I’ll need to read it several times to understand it all fully.

Thanks! I hope you find it helpful!