Dive into an engaging review of Gary Taubes’ ‘The Case for Keto,’ shedding light on the prevailing misconceptions surrounding ketogenic diets.

This isn’t just a critique of Taubes’ latest book but also a broader discussion about the low-carb and keto movements, offering readers a well-rounded understanding of these dietary trends.

If you’ve been swept up by the keto craze or simply curious about the science behind it, this review promises a rich blend of insights and analyses that might just reshape your dietary outlook.

- The good

- Taubes’ research

- The Title: The Case For KETO

- This book is really about the benefits of a lower carb Atkins style diet (not keto)

- ‘Keto’ has an identity problem!

- What is a ‘ketogenic diet’ anyway?

- Exogenous versus endogenous ketosis – the important differentiation!

- Ketones are transient

- Should ‘keto’ be the end goal?

- What happens to ketone levels on a ‘ketogenic diet’ over the long term?

- Will I get fat if I eat carbs?

- The fat+carb danger zone

- Is it just because the food tastes good?

- The rise of fat+carb combo foods

- Carbs are NOT new to the human diet

- It’s all about satiety!

- Insulin is not the enemy!

- Are you someone who “fattens easily”?

- Bottom line

The good

Firstly, you have to give Taubes credit for doggedly advancing the case for the low-carb diet ever since he wrote The New York Times article What if It’s All Been a Big Fat Lie? back in 2002.

Many people, including my wife Monica, who lives with Type 1 Diabetes, have benefited from the low carb and keto movements who have made a lower-carb diet a more acceptable approach.

In 2011, Taubes wrote Why We Get Fat: And What to Do About It, which has shaped the thinking of the low carb and keto movement immensely.

Then, in 2017, after many people pointed out that there were plenty of populations thriving on a low-fat high-carb diet, Gary wrote The Case Against Sugar, painting sugar as dietary villain #1.

And now, we have The Case For Keto.

Taubes’ research

Taubes, along with Peter Attia, has been instrumental in asking the questions and assembling the funding to, through their Nutritional Science Initiative, ask and investigate some of the most interesting and important questions in nutrition and metabolism. In 2012, they pulled together USD$40,000,000, mainly from the John and Linda Arnold Foundation, to launch the “Manhattan Project for Nutrition”.

However, sadly, it seems that, in spite of the learnings from valuable studies he has instigated, his thinking hasn’t changed much since 2002. Rather than telling you about what they learned after spending $40m+ on research, Taubes seems to have brushed that little episode under the carpet and continues to re-tell the stories of centuries past, his old favourites.

As an aside, NuSI only partially funded the experiments. Their partner institutions (e.g. Standford and the National Institutes of Health) also came to the table with large sums of research money. Since the NuSI days, Dr Kevin Hall has continued a barrage of expensive metabolic ward experiments in humans, apparently worth more than $100m, trying to kill Tabues’ pet Carbohydrate Insulin Model of obesity. That’s a lot of research funds trying to win a glorified Twitter war that could be spent on more valuable research, feeding malnourished children, providing cheaper insulin to people with Type 1 Diabetes who are dying without it, or any number of more valuable pursuits.

Taubes is an investigative journalist who tells meticulously detailed and engaging stories that cast doubt on mainstream dietary recommendations. If you are a low carb or keto proponent who wants your current beliefs reaffirmed with more of what you have loved from Gary in the past, you will love this book.

But, unfortunately, it doesn’t do much to progress the science of nutrition. To quote Taubes in the introduction,

“This book is a work of journalism masquerading as a self-help book.”

The Title: The Case For KETO

The first problem I have with “The Case for Keto” is the title.

To be fair though, it’s not Gary’s fault.

Taubes has admitted that the title was the publisher’s idea to jump on the keto trend.

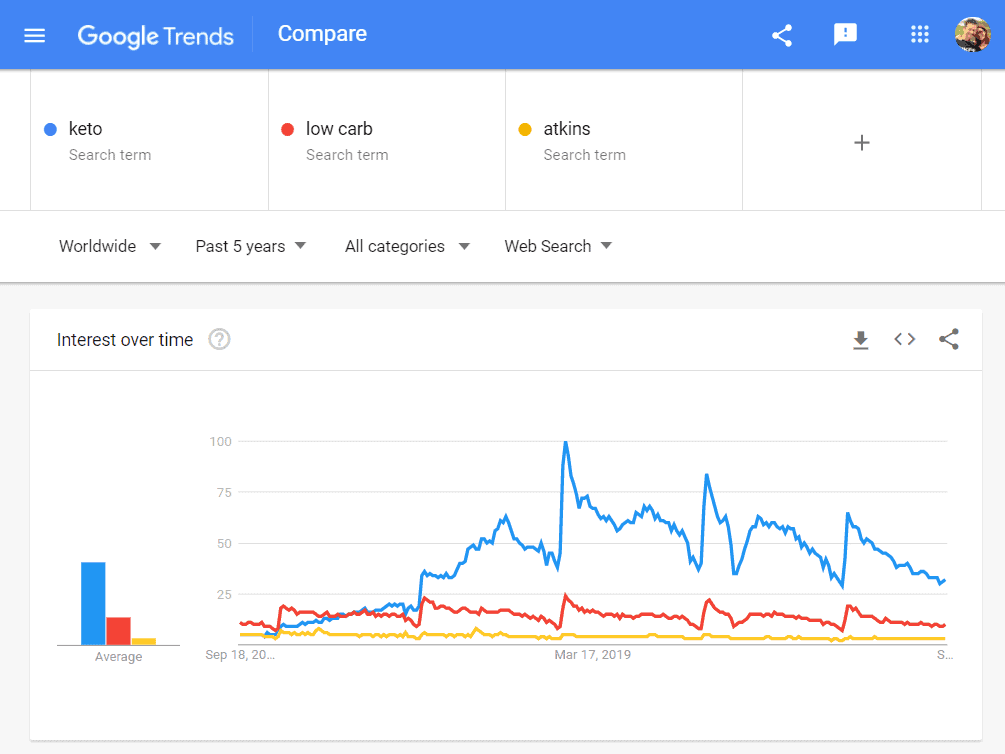

Although the popularity of ‘keto’ has been in decline for the past two years, it still far outstrips low carb, Atkins and many other popular diet trends/fads.

So ‘The Case for Keto’ makes sense, from a marketing perspective. He is preaching to the choir, the true believers who are still holding onto the life rafts of the sinking keto movement.

Meanwhile, the smartest people in the keto scene are trying to move on from the ‘keto’ label, including Diet Doctor CEO Andreas Eenfeldt…

and Craig and Mariah Emmerich.

Ironically, Taubes mentioned in his Diet Doctor interview that he originally wanted to call the book ‘In Praise of Fad Diets’ after being interviewed on why fad diet books were so popular. He had the epiphany that fad diet books are popular because people are always in search of an alternative to conventional advice.

This book is written targetted to the sceptics who would like to believe that they ‘fatten easily’ and they are fat and/or diabetic because the mainstream nutritional advice is wrong. It preys on people with a victim mentality who want to outsource the blame for their woes.

Later, the working title for the book became ‘How to Think About How to Eat’. When the publisher suggested The Case For Keto Gary said it ‘gave him the willies’. But it seems to have stuck regardless.

Taubes obviously doesn’t think there is much of a difference between low carb and keto. He said,

‘I don’t know when it became keto. It used to be Atkins, but you couldn’t write another book on Atkins’ because it had already been done.’

This lack of understanding and nuance is frankly disturbing.

This book is really about the benefits of a lower carb Atkins style diet (not keto)

Taubes doesn’t seem to differentiate between low carb, Atkins, nutritional keto and therapeutic keto, The Case for Keto is primarily the story of low carb and Atkins (with some fear of insulin and protein thrown in).

As a journalist, Taubes tells the history of the previous successful versions of lower-carb diets (not keto) including Atkins, Jean Anthemele Brillat-Savarin’s 1825 The Physiology of Taste and William Banting’s Letter on Corpulence. While you are reading a book titled The Case for Keto, these previous historical success stories are not really ‘keto’.

Although he does not say it (or perhaps even realise it), the book is arguing the case for a diet with less refined carbohydrates and a focus on protein.

‘Keto’ has an identity problem!

One of the problems that I have with ‘keto’ the word means so many things to so many people.

The term has become polarising and effectively meaningless.

While this is great for selling (fad?) diet books to a broad audience, the lack of precision often lead to confusion, stalled progress, and sadly, worsening metabolic health.

What is a ‘ketogenic diet’ anyway?

The most commonly accepted definition of a ‘ketogenic diet’ is one that generates ketones greater than 0.5 mmol/L.

Many people believe that ‘optimal’ (i.e. better?) ketosis occurs at higher levels. This often referenced chart from Phinney and Volek’s Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living shows that the ‘optimal ketone zone’ is between 1.5 and 3.0 mmol/L.

The classical or therapeutic ketogenic diet was developed early last century to treat kids with epilepsy. Extended fasting was found to control epileptic symptoms, but rather than long-term starvation, a more viable and sustainable solution was to increase the fat (while keeping carbs and protein very low) in the diet to the point that blood ketones became elevated.

In order to keep ketones elevated, a classical ketogenic diet typically consists of 80-90% fat. A ketogenic diet also tends to help people manage symptoms of Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and dementia.

This is wonderful for people who require a ketogenic diet. However, the vast majority of people who come to keto are not doing it for Parkinson’s, epilepsy, dementia or Alzheimer’s control – they want weight loss, diabetes reversal and improved metabolic health.

Exogenous versus endogenous ketosis – the important differentiation!

The confusion comes when we observe that the body also can produce ketones from our body fat, particularly in the initial phases of weight loss.

We can produce ketones endogenously (from the stored body fat that we want to lose) or exogenously (from extra dietary fat or exogenous ketone supplements).

Sadly, the differentiation between exogenous and endogenous ketosis is rarely made. People assume elevated ketones are magical, regardless of where they are coming from.

If you follow this logic, then:

- Ketones are good.

- More is better.

- Keto is the end goal.

What seems to be missed is that the appropriate dietary prescription for endogenous ketosis versus exogenous ketones is radically different.

This distinction is critical, particularly if you want to lose fat from your body and improve your metabolic health.

Ketones are transient

Back in the day, followers of the Atkins diet used urine ketone test strips during the induction phase to confirm that they were doing the diet right and they were ‘in ketosis’. However, it was acknowledged that this initial ketosis period was transient. After a while, your body would adapt and no longer spill ketones into the urine.

With widely available (although still outrageously expensive) blood ketone testing (created for people with Type 1 Diabetes to check for diabetic ketoacidosis), testing ketones has become more popular. They were deemed the ‘gold standard for measuring ketosis‘.

I had the privilege of having Professor Steve Phinney (pictured below in our kitchen) stay at our place when he spoke at a Low Carb Down Under event in Brisbane in 2016.

While I had him as a captive at my place for a couple of days, I quizzed him about the basis of his ‘optimal ketosis’ chart.

Steve said the chart was based on the blood ketone levels of participants in two studies done in the 1980s. The first was with cyclists who had adapted to ketosis over a period of 6 weeks. The second was a weight loss study where people were put on a ketogenic diet.

The critical thing to note is that, in both cases, ‘optimal ketone levels’ (i.e. between 1.5 and 3.0 mmol/L) were observed in people who had recently transitioned to a lower-carb or ketogenic diet.

However, as more people have ‘gone keto’, many people find that their blood ketone levels continue to decrease after a few weeks or months (even though they are still following a ‘ketogenic diet’).

We now know that, over time, ketone levels in our blood decrease as we become more metabolically healthy (i.e. lower blood sugars, lower body fat, lower waist:height ratio).

Most people move beyond the ‘keto-adaptation phase’ as their bodies learn to use fat more efficiently in the citric acid cycle rather than ketosis (which you can think of as a backup pathway in times of starvation).

As they reduce body fat levels, they are able to store excess energy from their diet in their adipose tissue, and their ketone levels reduce even further. They move back below their Personal Fat Threshold, and they no longer need to spill excess energy into their bloodstream (in the form of glucose, free fatty acids or ketones).

Interestingly, the Inuit, who are often touted as an example of people who thrive on a very low-carb diet, have a genetic adaptation, so they see even lower levels of ketones on a high-fat diet. Perhaps our bodies don’t like to be perpetually ‘in ketosis’ because ketosis is less efficient in oxidising fat than the default citric acid cycle when there is adequate oxaloacetate from protein and carbs.

This leaves many, if they want to keep their ketones in the ‘optimal’ range, people faced with the decision to either:

- continue to add more refined fat (e.g. butter, MCT oil, exogenous ketones etc.) to maintain ‘optimal ketosis’, or

- reduce dietary fat to allow fat from their body to be used, thus improving their metabolic health, reversing their diabetes and reducing or obliterating obesity.

Should ‘keto’ be the end goal?

The chart below shows the sum of the blood sugar and ketones (i.e. total energy) from nearly 3,000 data points from a broad range of people who say they are following a low-carb or ketogenic diet. Blood ketones are shown in blue (on the bottom), while glucose is shown in orange (on the top).

On the right-hand side of the chart, we have a high-energy state where both glucose and ketones are elevated at the same time. While some people have high ketones and low blood glucose (likely endogenous ketosis, with ketones coming from supplements, not body fat), some people with high glucose and high ketones together (likely exogenous ketosis, from high levels of dietary fat).

This high-energy situation is similar to someone with untreated Type 1 Diabetes with high glucose and high ketone levels due to inadequate insulin – their stored energy flows into their bloodstream, and they see elevated levels of glucose, ketones and free fatty acids.

Meanwhile, on the left-hand side of the chart, we see people with a lower total energy in their bloodstream. Because they store and use fuel efficiently, metabolically healthy people don’t need to have large amounts of glucose or ketones circulating in their bloodstream.

What happens to ketone levels on a ‘ketogenic diet’ over the long term?

It’s interesting to see how my crowd-sourced ketone data aligns with data from the Virta study one-year results (Phinney et al., 2017).

The distribution of BHB levels after 10 weeks of the Virta trial are shown in the chart below. Towards the right, we see that there were a few people with higher ketone values, many people also had values of less than 0.5 mmol/L, even during the initial adaptation phase.

It’s important to note here that, despite consuming a ‘ketogenic diet’ under the supervision of the Virta Team, most of the study participants did not achieve ketone levels that qualified as ‘nutritional ketosis’ (i.e. BHB > 0.5 mmol/L).

The next chart shows the average ketone levels of people participating in the Virta study over the first year (from Effectiveness and Safety of a Novel Care Model for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes at 1 Year: An Open-Label, Non-Randomized, Controlled Study).

We see that blood ketone levels initially rose from 0.18 mmol/L at baseline to 0.6 mmol/L in the first few weeks. But from there, blood ketone values decreased to 0.27 mmol/L after a year. This is well below the minimum threshold for nutritional ketosis (i.e. BHB > 0.5 mmol/L), let alone the ‘optimal ketone zone’ (BHB > 1.5 mmol/L).

As shown in the chart using data from Virta’s study 2-year results (Long-Term Effects of a Novel Continuous Remote Care Intervention Including Nutritional Ketosis for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes: A 2-Year Non-randomized Clinical Trial), blood ketone levels remained at 0.27 mmol/L after 2 years of a ‘ketogenic diet’ as people continued to lose weight and improve their diabetes. I am looking forward to seeing the three-year results from the Virta trial. I imagine that ketone values will remain stable, or even decrease.

We have seen a similar trend with ketones in our Nutrient Optimiser Masterclass. Blood ketones tend to rise for a couple of weeks when people focus on high-satiety nutrient-dense meals. However after a few weeks, blood ketone levels decreased as people continued to lose weight and lowered their blood sugars.

If you are on a ketogenic diet, relatively metabolically healthy and lean, and not overdoing the refined dietary fats, you may see BHB ketone values between 0.3 and 1.5 mmol/L. Ketones will be higher if you are fasting, restricting calories, exercising or consuming more dietary fat. But remember that blood ketones will likely decrease over time as your metabolic health improves. Many people conclude that being concerned about blood ketones is not worth the expense, pain and hassle.

OK. That’s enough pedantic ranting about ‘keto’. Obviously, I think it’s an important and much-maligned topic.

I fear that a book called ‘The Case for Keto’ will inspire another surge of people chasing elevated blood ketones and then drinking butter and MCT oil to keep them high over the longer term (which is where I was five years ago when the photo on the left was taken).

I’ll move on to some of the other elements of ‘The Case for Keto’ that frustrated me.

Will I get fat if I eat carbs?

Taubes firmly believes that carbs (which raise insulin more in the short term) are the dietary devil. He says:

The culprits, specifically, are sugars, grains and starchy vegetables. For those who fatten easily, these carbohydrates are the reason they do.

I’m not going to make the case for nutrient-poor refined carbohydrates, but it’s worth highlighting that, at least since 1999 when the FDA approved artificial sweeteners, obesity has NOT tracked with carbohydrate intake.

When sugar intake started to decline in 1999 and was replaced by synthetic sweeteners, obesity continued to climb. This divergence in the data should cast some doubt on carbs and/or sugars as being the primary or only culprit in our growing waistlines and worsening metabolic health. Nutrient-poor refined sugar is not a healthy food and does convert to fat in the liver, but it is not the only piece to the obesity puzzle.

Taubes should know that a high-carb diet doesn’t necessarily make people fat. The partially NuSI-funded year-long DIETFITS study with more than 609 participants (Effect of Low-Fat vs Low-Carbohydrate Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss in Overweight Adults and the Association With Genotype Pattern or Insulin Secretion: The DIETFITS Randomized Clinical Trial) found that (regardless of genetics, insulin levels or blood sugars), participants following either the low-fat or low-carb diet achieved similar weight loss and improvements in metabolic health.

The researchers initially encouraged participants to pursue a diet as low in carbs or fat as they could achieve and then back off to a level that they thought was sustainable for the long term. As you can see from the comparison charts below, both the low-fat and the low-carb arm lost a similar amount of weight.

The key observations from the DIETFITS study were as follows.

- Following either a low-carb or low-fat diet can help to reduce the hyperpalatable, highly processed junk food in our diets that typically causes us to eat more than we need to.

- Over time, most people gravitate back to hyperpalatable junk food (which is typically a combination of nutrient-poor fats and carbs).

- It was the people who changed their DIET QUALITY who had the most significant long-term success. These people experienced increased satiety and no longer felt like slaves to their appetites.

In a recent interview, lead researcher Professor Chris Gardner stated that, rather than pursuing a magic macronutrient ratio, defining diet quality in a way that leads to satiety is the next exciting frontier of nutritional science.

The fat+carb danger zone

Speaking of satiety, the chart below is from our analysis of 587,187 days of food logging. The vertical axis shows the reported daily calorie intake in MyFitnessPal divided by the users’ target calorie intake. A value toward the bottom means that they consumed less than their goal (and vice versa). We divided the data up based on their carbohydrate intake (shown on the horizontal axis).

As indicated by the green line, we tend to eat a greater quantity of food when that food contains a combination of fat and carbs (e.g. doughnuts and croissants). Reducing the carbohydrates in your diet tends to help you eat less, but only up to a point. To the right, it is tough to over-consume foods with a very high carbohydrate content and very low fat (e.g. broccoli, plain rice and plain potato).

If you want to experiment, try eating nothing but plain rice or potato for a week (with no added oil). In the absence of fat, carbs alone are incredibly hard to overeat!

This data suggests that pushing carbs even lower (i.e. to ketogenic levels) appears to align with a greater calorie intake. The best satiety outcome tends to occur when carbohydrates make up about 25% of total calories (i.e. lower carb by not very low carb).

Is it just because the food tastes good?

In their last-ditch effort to revive the Carbohydrate Insulin Model after being declared dead by many, Taubes and friends noted that many studies show that mice do not necessarily eat more of a diet that is flavoured to be tastier but still have the same macronutrient profile. Humans and mice don’t eat more just because the food tastes good unless it enables us to fill both our fat and carb stores simultaneously.

The rise of fat+carb combo foods

This next chart shows the change in energy from each of the macronutrients in the food system over the last century. While carbs (red line) have increased (then decreased) over the past 50 years, the amount of fat (blue line) has been steadily on the increase over the past century! The amount of fat in our diet has risen by around 600 calories per person per day!!! If dietary fat was not fattening and keto was the holy grail, we should not be seeing such an ominous rise in obesity!

Since we worked out how to extract refined fat from soybeans, corn and rapeseed in 1908, the amount of fat in our diet has risen steadily.

Combined with the large-scale farming practices and agricultural subsidies implemented in the 1960s, the availability of calories per person (mainly from fat and carbohydrates, not protein) has skyrocketed.

If we zoom in and look at the past 50 years, we see that an increase in both fat and carbs has contributed to our increasing calorie intake (which has tracked closely with obesity). Protein (green line) has only increased marginally while both fat (blue line) and carbs (red line) have increased a LOT. Overall, since the lows of the 1960s, energy availability has increased by around 1000 calories per day per person in the US, with similar trends occurring across the globe.

But before we say that all fat is bad, we need to look at where that extra fat has come from. When we look at the growth in extra calories by food group, we see that the increase in ‘salad and cooking oils’ (purple line at the top of the chart) tracks closely with obesity.

The increase in easily accessible energy from both refined grains and refined fats from large-scale agriculture is the smoking gun or the ‘elephant in the room’ of the obesity epidemic.

Carbs are NOT new to the human diet

Taubes says:

The very simple assumption underlying the LCHF/ketogenic diet is that it’s the carbohydrate-rich foods we eat that make us unhealthy: both fat and sick. These are relatively new additions to human diets, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that removing them can improve our health.

Before widespread industrial agriculture, people closer to the equator lived on more of a carbohydrate-rich diet, while people towards the poles in colder climates lived on lower-carb fat-rich diets.

Our macronutrient content continually varied throughout the year, with more fat in winter (when animals were fat) and more carbs in summer when crops were ready for harvesting.

Autumn was the only time when foods that are a combination of fat and carbohydrates together were available. This unique combo signalled to our body that we needed to eat more to fatten up to survive the winter. In spring, the lean protein and new fibrous plants let us lose the winter blubber.

This still occurs in nature for animals in their natural habitat (this is the same bear – Beadnose – in spring and autumn).

What is new is the continual availability of fat and carbohydrates at the same time in the same place.

Both fat and carbs have risen over the past 50 years. Fat from refined vegetable oils has become much more prevalent in our diet over the past century. This is great for food manufacturers who can produce high-profit margin foods from refined fat combined with refined grains and sugars, but not so great for our metabolic health.

When we look at our macro intake in percentage terms over the past century, we see that obesity started to skyrocket when our intake of carbs and fat approached similar levels.

It’s all about satiety!

In a number of instances in The Case for Keto, Taubes mentions that the reason a low-carb diet works is that we are able to control our appetite. For example:

And no matter how fat we might be, this way of eating does not advise us to consciously eat less or control our portions or count our calories or attention to how much is too much… It advises us to eat when we are hungry and then eat to satiety, with the expectation that eating to satiety will be relatively easy to accomplish.

This is where he gets close to the money but then drops the ball and attributes the satiety to the high-fat diet.

It’s true that a lower-carb diet does help us to eat less. This is where the magic of a reduced carbohydrate diet occurs – when we avoid all the ‘bad carbs’ like cookies, doughnuts, and croissants.

But we also struggle to overeat a very low-fat, high-carb diet (e.g. potato, rice, veggies etc.) with no added fat. People who are able to stick to a whole foods plant-based diet are rare, but they are typically not obese due to the carbs.

Proponents of the plant-based diet like to point to the Blue Zones, where people ate a high-carb diet (e.g. Kitavans and Okinawans) and tend to have the longest-lived populations (they neglect to mention that food is generally hard to get and is also minimally processed).

However, in our modern food environment, where Big Food likes to sell us what we love to eat, most people gravitate to the hyper-palatable danger zone of fat+carbs that enables us to overeat.

High-fat foods are actually much less satiating than low-fat foods on a calorie-for-calorie basis.

The magic really happens when we reduce carbs and we tend to increase the protein in our diet. As per the Protein Leverage Hypothesis, our bodies require protein. If our diets are low in protein, we continue to chew through calories until we get the protein (and other essential nutrients) needed.

When we compare all the macros, we see that both fat and carbs have a negative impact on satiety. Fibre has a small positive impact, but the protein has the biggest positive impact on satiety by far!

The data from our analysis of 1800 recipes for Nutrient Optimiser shows that reducing carbs tends to increase our protein intake.

Sadly, when their only goal is ‘keto’, many people end up avoiding protein for fear of losing their ketones or raising their insulin levels after they eat (as recommended in The Case for Keto).

I see a lot of confusion and controversy in the low-carb and keto scene around finding the right balance between dietary fat, dietary protein and body fat. In the chart below, I have shown some notional divisions between:

- Therapeutic keto (for managing epilepsy, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, dementia etc.).

- Nutritional keto (for the active lean person who enjoys a low-carb diet with some extra fat).

- Low carb (for people who are at their goal weight but not as active)

- Low carb and fat loss (to allow fat to come from your body rather than your diet), and

- Protein Sparing Modified Fast (very high protein for maximum satiety and rapid fat loss).

Basically, if you want to use more fat from your body, you need less fat in your diet. You will also get more nutrients per calorie, so you can thrive on fewer calories. But sadly, due to lazy book titles sold into the keto craziness, many people are still chasing a therapeutic ketogenic high fat diet that will drive lower satiety and excess energy intake.

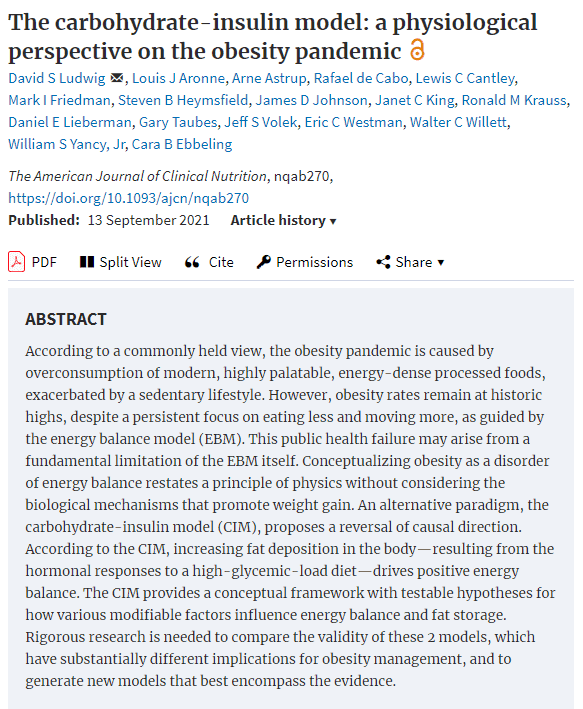

Insulin is not the enemy!

Over the years, Taubes has been a major proponent of the Carbohydrate-Insulin Hypothesis. And despite all the NuSI-funded research that he instigated, he has not changed his view. He says:

Specifically, carbohydrate-rich foods create a hormonal milieu in the human body that works to trap calories as fat rather than fuel. At the very least, if we want to avoid being fat or return to being relatively lean, we have to avoid these foods. They are quite literally fattening.

All diets that result in weight loss do so on one basis and one basis only: they reduce circulating levels of insulin.

Basically, the Carbohydrate-Insulin Hypothesis simplistically assumes:

- carbs -> insulin -> fat storage

This theory is partially true. but again, the ‘experts’, who should know better, continue to conflate exogenous insulin (from outside the body) with endogenous insulin (produced by your pancreas, inside your body).

If someone injects excessive amounts of exogenous insulin, their liver will hold their stored energy back, the energy in their blood will decrease, and they will get extremely hungry and be compelled to eat more food, thus gaining fat.

However, this ‘fun fact’ is completely irrelevant for the 99.95% of the population that has a working pancreas. It would be illegal for someone to go around jabbing you with a needle to inject you with insulin throughout the day. They would be deemed a dangerous public nuisance and locked up!

Our bodies have evolved to be super-efficient. It does not produce more of anything than it absolutely needs to. Your pancreas will not release any more insulin than is required to keep your stored energy in storage while food is coming in via your mouth.

The chart below shows that total insulin demand across the day positively correlates with your body mass index (BMI). Your insulin requirement across the day is driven by the amount of energy your body holds in storage.

People with Type 1 Diabetes know they need to use basal insulin (to keep their blood sugars stable when they don’t eat) and bolus insulin (for their food).

For people on a standard high-carb diet, basal insulin makes up around 50% of their total daily insulin, while the rest is injected to manage their meals. However, for people on a low-carb or keto diet, basal insulin can make up as much as 90% of their daily insulin requirements.

So, unless you are able to switch off your insulin pump or choose not to take your injections and let your blood sugars run high (also known as diabulimia, a dangerous eating disorder practised by some people with Type 1 Diabetes), the only way to reduce the insulin produced by your pancreas is to focus on eating higher satiety foods that will enable you to consume less energy more easily.

So rather than:

eat more carbohydrates -> make more insulin -> get fatter

what appears actually to be driving obesity is:

low satiety nutrient-poor foods -> increased cravings and appetite -> increased energy intake -> fat storage -> increased daily insulin

Reducing the processed carbs in your diet will help stabilise your blood sugars (i.e. symptom management). But if you want to lower your insulin requirements, reverse Type 2 Diabetes and address energy toxicity (the root cause of most of our metabolic diseases), you should prioritise nutrient-dense, high-satiety foods and meals that will enable you to reduce your insulin levels throughout the day.

Thus, the real solution to managing Type 2 Diabetes, blood sugar, insulin levels, obesity and avoiding the myriad complications of metabolic syndrome is:

high-satiety nutrient-dense foods and meals -> decreased cravings and appetite -> decreased energy intake -> fat loss -> optimised insulin levels

Are you someone who “fattens easily”?

Gary appeals to the victim mentality of people who would like to believe they “fatten easily”.

Fat people are not lean people who eat too much.

Those who fatten easily are fundamentally, physiologically and metabolically different from those who don’t.

Fat people are not lean people who eat too much…We have to eat differently because we are different.

People with obesity… [are] people whose bodies are trying to accumulate fat even when they’re half-starved. The drive to accumulate fat is the problem, and it’s the difference between the fat and the lean.

No one wants failure to be their fault. They want to blame something or someone else.

And, while the fact that obesity has grown so rapidly over the past half-century (wherever processed hyperpalatable processed foods are sold) can make us feel like helpless victims, it’s important to place the blame at the feet of the correct perpetrator so we can reverse the situation.

Everyone wants to feel like a unique snowflake and that there is something about THEM that makes them fatten more easily. However, I am not aware of any research that demonstrates that certain people fatten more easily with carbs due to their genetics.

However, there are definitely differences in how we fatten. Professor Roy Taylor’s work on the Personal Fat Threshold has elucidated this beautifully. Some people are ‘blessed’ with the ability to store heaps of fat in their subcutaneous adipose tissue (e.g. bum and belly) before it gets stored around their vital organs (visceral fat).

Others, sometimes known as TOFI (thin on the outside, fat on the inside), may look lean, but meanwhile, their organs are surrounded by fat, and the excess energy they eat spills over into their bloodstream as glucose, ketones and fatty acids.

If your blood sugars are elevated above the healthy range after meals (i.e. they rise by more than 1.6 mmol/L or 30 mg/dL), then it absolutely makes sense to dial back the refined carbs in your diet to achieve healthy, stable blood sugars. But similarly, if you have more body fat than you want, it makes sense to dial back the dietary fat to allow your body fat to be used as energy. This is not magic; it’s just how our physiology works.

While we all want to feel like a unique snowflake, I believe we are more similar than different. The vast majority of people exposed to the hyperpalatable autumnal combination of refined fat and refined carbs (with low protein) tend to fatten quickly.

Your body has evolved to LOVE these foods because you get a double dopamine hit from the easily digested energy from fat and carbs at the same time. Gary believes that carbs lead to increased insulin which “traps fat” and makes you feel like you are half-starved. A more useful way to view this phenomenon of appetite dysregulation is the fact that we are getting a double dopamine hit from these foods that leads to an uncontrollable binge because your body believes it needs to prepare for winter (like Beadnose the bear).

While I agree with Gary that simply trying to manage calories in vs. calories out is overly simplistic for most people living in the real world. Managing hunger and satiety is critical to achieving energy balance for anyone living outside a metabolic ward where all the food is weighed and measured.

But it’s not just the carbs.

It’s the nutrient-poor, low-satiety carb+fat combo that leads to a dysregulated appetite which leads to excess fat accumulation. Once we have accumulated excess body fat stores, your pancreas needs to secrete more insulin to store that energy.

Increased insulin is the result of obesity, not the cause.

‘Going keto’ by targeting more fat and perhaps less protein is not the cure. In fact, it will likely make things worse.

Bottom line

- I’m frustrated that low-carb thinking has not progressed much over the past 18 years.

- The Case for Keto will only serve to perpetuate and further entrench the dogma.

- Science has evolved to enable us to harness the power of a reduced carbohydrate diet to maximise satiety (as well as nutrient density) and improve our health.

- We can tailor this to suit our context and goals rather than rigidly subscribing to a one-size-fits-all approach that all too often, and unnecessarily, leads to a dead end.

Big Fat Keto Lies

If you’ve found this interesting, you may enjoy the following samples of the chapters from Big Fat Keto Lies.

- Big Fat Keto Lies: Introduction

- A brief history of low-carb and keto movement

- Keto Lie #1: ‘Optimal ketosis’ is a goal. More ketones are better. The lie that started the keto movement.

- Keto Lie #2: You have to be ‘in ketosis’ to burn fat

- Keto Lie #3: You should eat more fat to burn more body fat

- Keto Lie #4: Protein should be avoided due to gluconeogenesis

- Keto Lie #5: Fat is a ‘free food’ because it doesn’t elicit an insulin response

- Keto Lie #6: Food quality is not important. It’s all about reducing insulin and avoiding carbs

- Keto Lie #7: Fasting for longer is better

- Keto Lie #8: Insulin toxicity is enemy #1

- Keto Lie #9: Calories don’t count

- Keto Lie #10: Stable blood sugars will lead to fat loss

- Keto Lie #11: You should ‘eat fat to satiety’ to lose body fat

- Keto Lie #12: If in doubt, keep calm and keto on

Marty, great review!! Having followed and read the books, both Taubes and others over the last 15 years, your program makes the most sense practically and scientifically!

Excellent article Marty!

Thanks for continuing to publish real-world helpful analyses, insights and recommendations

Cheers!

thanks Bob for your enthusiastic support and friendship! so great to have you as part of the community.

I wish you had written this article independently of a critique on Gary Taubes. I found it very interesting. I question your intentions though to use Gary Taubes as your hook to sell your book and your perspective. Why not write this article as a counter to keto popularity without jumping off Gary’s popularity? I actually found your book a couple of days ago because of links from ‘The Case for Keto’ but didn’t buy it because it was not readily available on Amazon. I think very highly of Stephen Phinney, his studies, work and writings. Do you show him in your kitchen to bolster your credibility? Your article was very intriguing and I will study it more but the above two points leave a distaste in my mouth.

thanks for checking out the article CC. I have been writing tons of stuff on this blog for the past five years unpacking my journey navigating nutritional fact, beliefs and dogma. this article was my response to Gary’s book. you will find plenty of other reviews congratulating him for another great book, but this was my honest response. I too have much respect for Steve Phinney and his contributions to nutritional science, however, I believe the concept of ‘optimal ketosis’ and continually chasing ketone as the end goal is leading many to a dead end in their nutritional journey. I have discussed this with many of the low carb leaders over the years, but nothing has changed. I think it’s important and will be the fatal flaw that kills keto and rob many people from getting the full benefits that they could from a nutrient-dense lower carb approach. science (including nutrition) needs to be about good data analysis to move beyond personalities and communities who believe the same thing. no one is infallible. I look forward to your thoughts as you ponder the data further. let me know if you see anything that needs to be updated or corrected.

Thank you for this interesting analysis. Your point of ketosis as a transient feature and not as a goal by itself, is refreshing. Even though “Increased insulin is the result of obesity, not the cause” sounds plausible, how about some transiency in there as well?

Enter Kraft test with ever increasing insulin peaks and lenghtening excretion durations, AUC of insulin multiplying by factors. Add to this the 4-5 fold faster metabolic rate of visceral fat cells, and we get TOFI or growing waist/hip ratio. The “bolus” takes gradually over the “basal”, with prevalent storage mode and subsequent hunger (need for snacks?). This “energy poisoning” (your word!?) is complete when fat cells become over-full and start leaking into blood. We had some discussion on Dietfits finding on fat cell size… the fill up sooner with lower-fat diet.

So, it is not the insulin per se, it is the transformation to chronic imbalance of insulin excretion. The way back is extreme carb or extreme fat avoidance, both with stabilizing effect on insulin. The sooner the start, the less modulation is needed. From you we have learned that protein is good to be prioritized. In the end, eat to satiaty, naturally not-so-frequently and moderate amount. Follow the hunger and satiety.

Well, this is my educated impression and hypothesis, I am open to refine it. As I have already done in your pages.

JR

thank you. good synopsis JR. my only point of contention is that basal continues to rise with obesity/IR. based on T1Ds basal makes up 50-90% of total insulin daily dose. and I don’t think most people do well with ‘extreme’ anything, but rather gradual changes (e.g. less refined carbs and added fats and a focus on nutirent density). use the minimum effective dose to get the results you need and keep titrating up as required to see continued results.