Trends and fads come and go. Ideas rise in popularity when someone discovers something that works. A few people apply this initial idea and got great results.

In time, entrepreneurial people realise there is money to be made and scramble to sell things to make it ‘easier’ and ‘more enjoyable’. Often, these marketers play fast and lose with the facts or don’t even understand them to start with.

Later, once the benefits of the original insights become diluted or more people move beyond the initial stage where the idea magically works, the trend begins to die. Before long, something fresh rises to take its place as people search for a new, quick, and easy fix.

Over the years, there have been several iterations of low-carb and keto, each with its unique emphasis, whether it be ketones, insulin, protein, fat, or something of the like.

Before we dive into dissecting the dogma and conflicting theories in nutrition, I thought it would be helpful to give you a quick tour of the different versions that have come and gone.

See if you can spot the common themes of successful lower-carb diets and the different emphases over the years.

Banting

One of the earliest versions of low-carb was the ‘Banting Diet‘, prescribed to English undertaker William Banting by Dr Harvey in 1862. Dr Harvey recommended a lower-carb, protein-focused, whole food diet that became super popular. Harvey had learned about the benefits of a low-carb diet to manage diabetes after attending lectures in Paris led by French physiologist Claude Bernard.

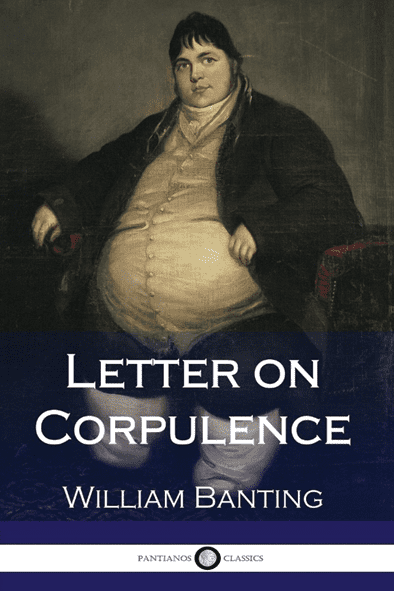

In 1864, Banting wrote a short booklet called Letter on Corpulence, Addressed to the Public as a testimonial of his success on Dr Harvey’s advice. His daily diet consisted of four meals consisting of meat, greens, fruits, and dry wine. Banting’s ‘before and after’ images are shown on the cover of two versions of his booklet, perhaps the first low-carb diet book in history.

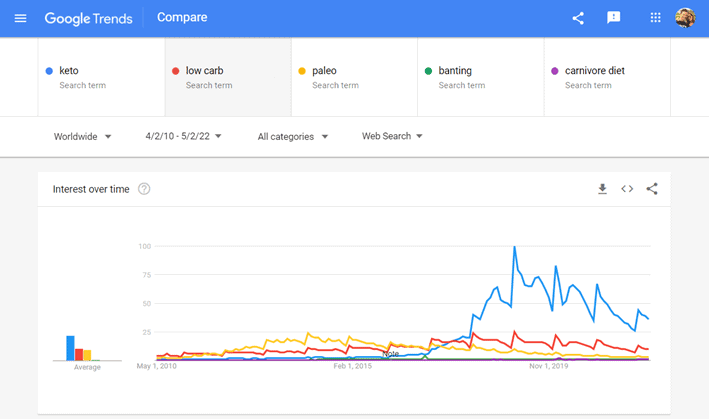

The term ‘Banting’ made a comeback in 2014 (as shown in the chart from Google Trends below), where it was spearheaded by South African Professor Tim Noakes. Noakes advocated a low-carb, high-fat version of the Banting diet and was careful not to overemphasise protein so that insulin remained low.

Dr Richard Bernstein

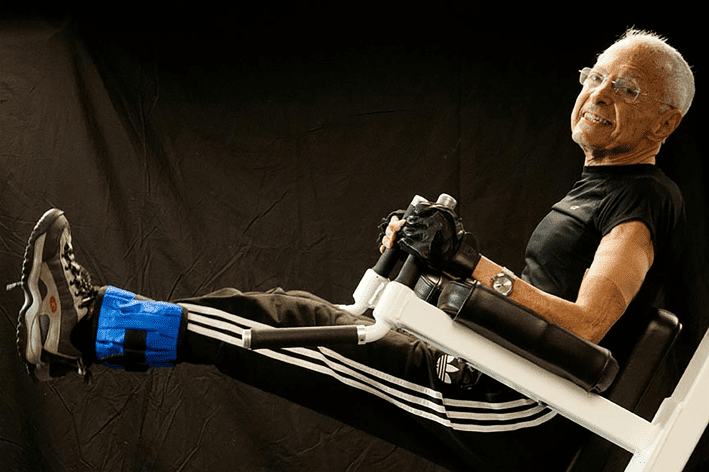

My family owes a massive debt of gratitude to the work of Dr Richard Bernstein and his followers. Dr Bernstein, who is thriving with Type-1 Diabetes at the age of 87, is an excellent example of how powerful carb reduction can be for people who are injecting insulin. Dr B (as his followers affectionally know him) also walks the talk in terms of maintaining strength to maximise insulin sensitivity and resilience.

Bernstein, who has had Type-1 Diabetes since he was 12, was initially trained as an engineer. Through his wife, who was a doctor, he was able to obtain one of the first glucose meters in 1969 (pictured below).

Bernstein, an avid self-experimenter, measured his blood sugars six times a day. Over time, he understood how much a certain amount of carbohydrate raised his blood glucose levels and how much insulin was required to lower them.

By reducing the carbohydrates in his diet, he stabilised his blood sugars and insulin doses. Bernstein’s early learnings formed the basis of the basal/bolus insulin dosing calculations built into modern insulin pumps that many people with type-1 diabetes use today.

Bernstein initially published The Glucograf Method for Normalising Blood Sugar in 1981. At 45 years of age, he went to medical school and became a doctor to have his methods recognised. He later published:

- Dr Bernstein’s Diabetes Low Carbohydrate Solution in 2005, and

- Dr Bernstein’s Diabetes Solution: The Complete Guide to Achieving Normal Blood Sugars in 2011.

Bernstein’s recommended diet is centred around protein to promote the growth of lean muscle mass. It also includes plenty of non-starchy veggies to ensure you get adequate micronutrients.

While many fear and try to minimise insulin, Dr Bernstein emphasises injecting sufficient insulin to maintain stable blood sugars after eating protein (protein requires about half as much insulin relative to carbohydrates over the first three hours).

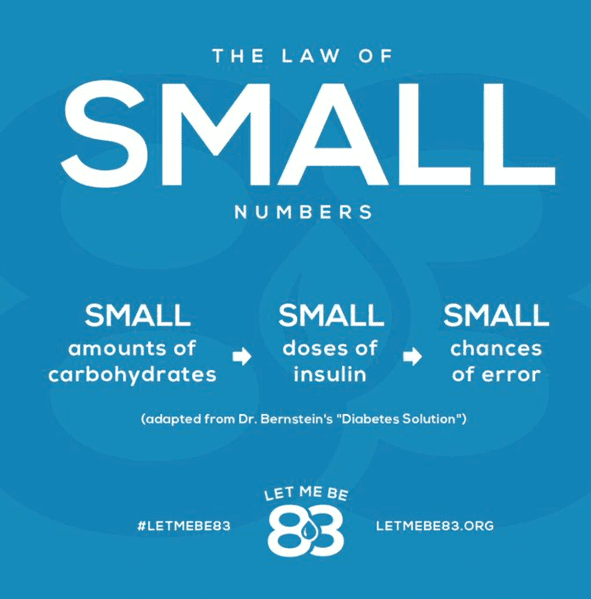

Bernstein’s approach to managing insulin and blood sugars revolves around ‘The Law of Small Numbers’. That is, large inputs of refined carbohydrates require large doses of insulin.

Due to the numerous variables involved, it is incredibly hard, if not impossible, to precisely calculate the insulin dosage needed for large amounts of carbohydrates. As a result, large inputs of carbohydrates and insulin lead to large errors and the constant need for correction.

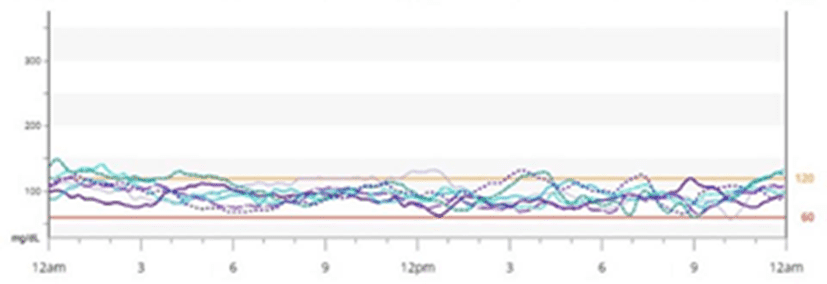

To illustrate what this looks like in practice, the chart below shows the blood sugars of someone with Type-1 Diabetes on a typical high-carb diet. Reducing the inputs of nutrient-poor processed carbohydrates reduces wild blood sugar swings and errors in insulin dosing.

The next chart shows the blood sugar control that can be achieved once the inputs of processed carbohydrates are reduced. Once we minimise blood sugar variability, we can bring down the overall average blood sugar without the fear of low blood sugars (hypoglycaemia).

Monica and I were fortunate enough to be introduced to the Type One Grit Facebook Group in 2015. We became believers after seeing the fantastic results that could be achieved for people living with Type-1 Diabetes.

As we have applied these principles, the improvements in Moni’s blood sugars, mood, energy, and weight have been life-changing. We are immensely grateful!

Bernstein’s low-carbohydrate diet was initially opposed by the American Diabetes Association, which recommended a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet for diabetics. In 2019, the American Diabetes Association changed its position to allow a low-carbohydrate diet as an acceptable option for diabetics. The UK NHS has also introduced a low-carbohydrate plan for diabetics and pre-diabetics.

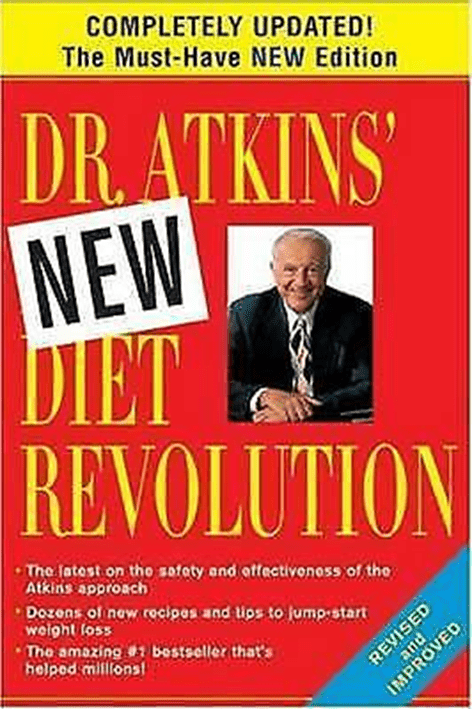

Dr Robert Atkins

Interest in ‘low-carb diets’ peaked in popularity thanks to the work of Dr Robert Atkins, who published his carbohydrate-restricted diet for weight loss in 1972.

Dr Atkins’ plan was focused on protein. While the definition of ‘low-carb’ can range from 20 to 150 grams of carbohydrates per day, Atkins recommended an initial low-carb induction phase where less than 20 grams of carbs were consumed without emphasising extra dietary fat. This initial phase was followed by introducing some carbs from nuts and non-starchy vegetables, so long as the desired progress continued.

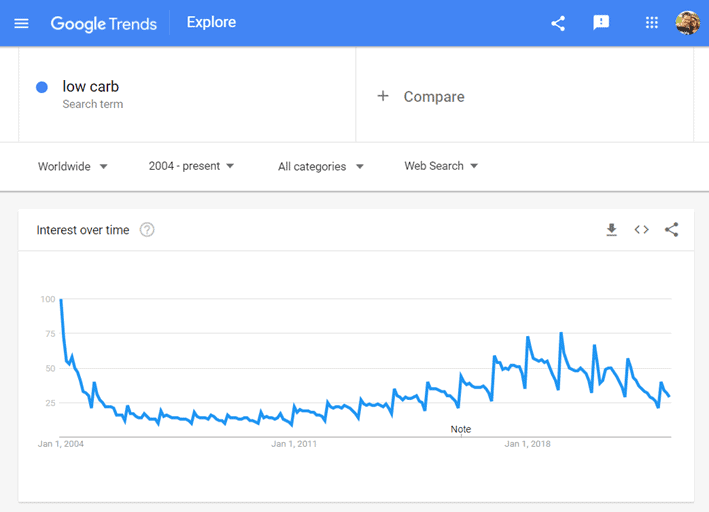

After Atkins died, interest in low-carb slumped to a low in 2008. Since then, low-carb has steadily grown in popularity—at least until January 2019—with each new wave of New Year’s resolutions bringing a fresh surge of interest in how to shed the Christmas pounds.

Good Calories, Bad Calories

Investigative journalist Gary Taubes‘ 640-page tome Good Calories, Bad Calories (2007) created a comprehensive story about why carbs and insulin (rather than fat) could be behind the obesity epidemic.

Taubes highlighted the way hormones trigger appetite during growth spurts and pregnancy. He also showed the correlation between the introduction of sugar and refined grains to the native American diet (i.e. Pima Indians) and the subsequent growth in obesity.

After realising plenty of populations had been doing fine on a high-carb, low-fat diet, Taubes published The Case Against Sugar (2016), painting sugar as the primary perpetrator of our metabolic woes.

These books have played important roles in cementing fears of insulin and carbohydrates into the psyche of low-carb and keto followers. Taubes’ expansive narrative makes sense if you want to characterise one macronutrient as good vs bad. Good vs evil is imperative to any compelling story.

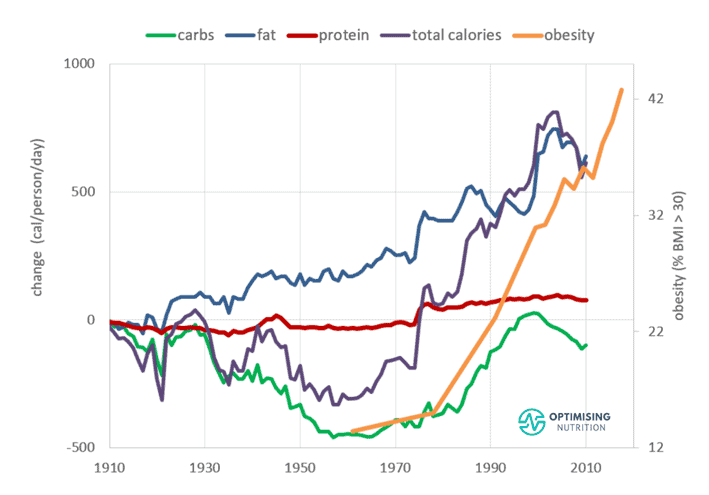

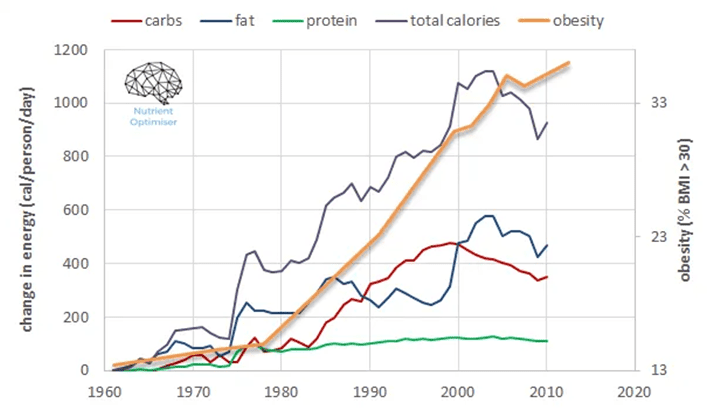

When you look at the increased carbohydrate intake between the 1960s and 2000, we can see that it correlates with the growth in obesity (at least up until 1999).

However, this ‘single macronutrient’ ‘good vs bad’ viewpoint neglects the fact that dietary fat, particularly from refined oils, has been on the rise in our food system for over a century.

When we look at the change in energy from all three macronutrients, we can see the increase in obesity aligns with a change in total calories, mainly from fat and carbs (data for charts from US Department of Agriculture Economic Research ServiceUnited States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service and the Centres for Disease ControlCentres for Disease Control).

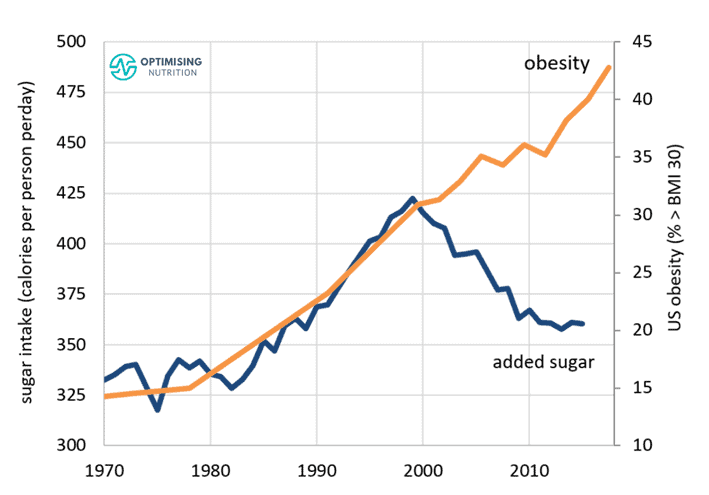

It’s also worth noting that our sugar consumption has significantly decreased since artificial sweeteners replaced high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in 1999. Although a constant supply of glucose and fructose (converted to fat in the liver) from sugar is far from optimal, this lack of correlation weakens the case against carbohydrates (and sugar) as the only culprit behind the diabesity epidemic.

Taubes, along with Dr Peter Attia, formed the Nutritional Science Initiative (NuSI) to bring clarity to the fat vs carbs debate. Funded mainly by the Arnold Foundation, which provided $40 million to fund the research, NuSi instigated several studies to test the validity of the Carbohydrate-Insulin Hypothesis of Obesity.

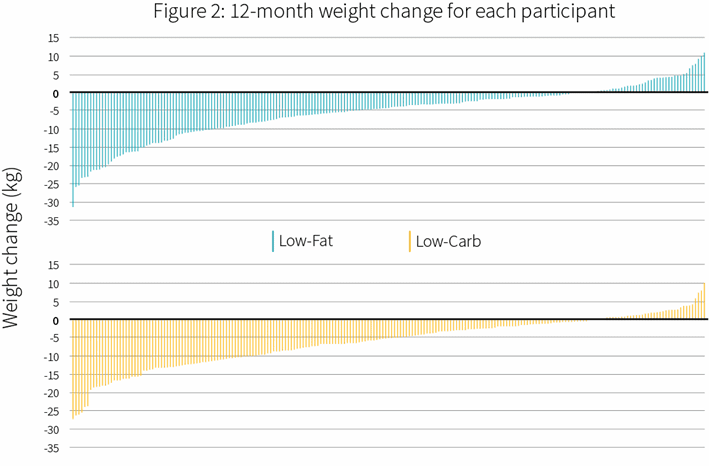

Admirably, NuSI chose lead researchers that weren’t necessarily already proponents of the hypotheses it was trying to prove to avoid confirmation bias. One of these studies that we will be discussing later was the DIETFITs Study led by Professor Christopher Gardener at Stanford, which inconveniently showed a similar weight loss with either low carb or low fat.

Another was the Energy expenditure and body composition changes after an isocaloric ketogenic diet in overweight and obese men led by Kevin Hall of the National Institutes of Health.

There has been plenty of debate around the interpretation of the study results, especially between Taubes and Hall. Since undertaking the NuSI study, Hall has led several studies that have cost in the order of $100 m to test the Carbohydrate-Insulin Model of Obesity and “to better understand how changes in fat vs carbs influence metabolic physiology, appetite regulation, and the role of insulin”.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t appear that many of the learnings from the studies that Taubes designed, arranged to fund for, and instigated have influenced his original narrative, which he reiterated in his recent book The Case for Keto.

Why Your Metabolism is Like the Stock Market

Before the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, I was fascinated by the art, science, and psychology of trading and spent a few years learning everything I could about the topic.

Before long, I realised there was no way I could know everything about the markets. Any news in the major press had already been factored into the price. Large investment funds have massive resources to understand market fundamentals that predict where the price will go in the future. Despite this, they often still get it wrong. While smaller traders can’t match this firepower, they can jump on emerging trends. I spent a couple of years designing and testing my trading systems on all the data I could get my hands on.

Similarly, human metabolism is incredibly complex. We cannot understand all the moving parts and how they interact exactly. So whenever we try to apply an overly simplistic theory, we fail. But we can stand back and look at inputs like macronutrients and micronutrients to understand how they influence the outcomes like energy intake.

We don’t have to understand how it works or reduce it to one overly simplistic mechanism. Although it’s always helpful to understand what we can about basic science, it’s often more helpful to use the most powerful levers that make the most difference and follow in the footsteps of other people who have already attained the results we are looking for.

In retrospect, my experience, alongside my engineering background, gave me the best foundation and training to approach quantified nutrition. It gave me the perspective to identify the levers that we can use to make the most significant difference to our health while discarding less useful theories that create noise.

While it’s great to do the research and try to understand how things work on a hormonal and biochemical level, you need to verify your theories with as much data as you can get your hands on to see if they help you achieve your goal in the real world.

Paleo

The Paleo Diet gained popularity in 2009, spearheaded by research biochemist Robb Wolf‘s book The Paleo Solution (2010). Interest in paleo peaked in January 2013, and paleo sadly never really escaped the wealthy, white, CrossFit scene to penetrate the mainstream.

While not definitively low-carb, paleo tends to be lower in carbohydrates because it eliminates refined grains. The work of Dr Bernstein also influenced Wolf, and he also thrives on a lower-carb diet.

Wolf’s second book, Wired To Eat (2017), included a 7-Day Carb Test where people are encouraged to check their blood sugar after meals to understand if they need to reduce their carbohydrates to achieve healthy blood sugar levels.

Paleo seemed to flourish so long as people saw it as foods ‘Grok the caveman’ or your grandma would have recognised. However, once paleo comfort foods and products emerged, the diet lost its efficacy and quickly declined in popularity.

As proponents of the program soon discovered, if your goal is weight loss, it’s not optimal to drown your sweet potato in butter or substitute processed foods with hyper-palatable, high-calorie concoctions of ‘paleo approved’ dates, honey, and coconut oil.

Carnivore

If low-carb is good, then cero-carb must be better, right?

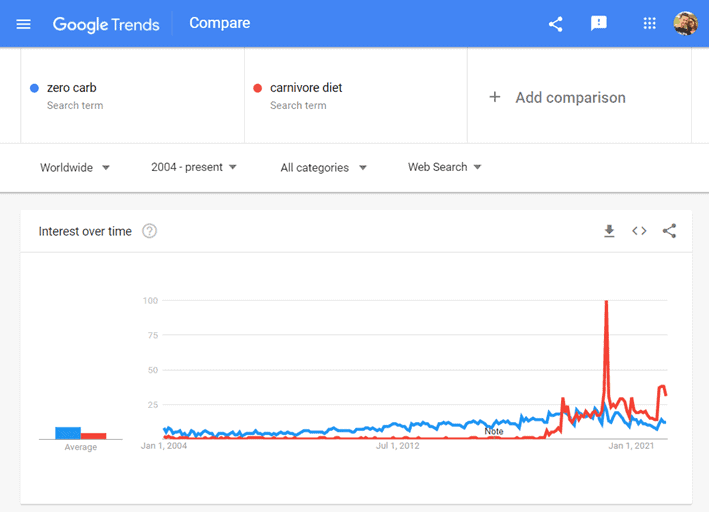

There has been an underground interest in Zero Carb for a while, but the ‘carnivore diet’ has overtaken Zero Carb over the past few years. While some people incorporate seafood and dairy, many simply advocate for ‘eat meat, drink water’.

L. Amber O’Hearn was one of the early carnivore advocates to manage her depression and bipolar and in an effort to manage her weight after low-carb. More recently, others have joined the carnivore tribe, like Dr Shawn Baker, author of The Carnivore Diet Mikhaila Peterson, Dr Paul Saladino, and the alternative health clinic Paleo Medicina that claims to use a paleo-carnivore diet to reverse chronic illness.

Many people with autoimmune issues have benefitted from eliminating plant foods in the short term and have seen great results. The carnivore diet provides plenty of bioavailable protein while eliminating the foods that people are most sensitive to. However, there are still plenty of arguments in carnivore circles over the appropriate balance between protein and fat from cross-pollinating the keto and carnivore communities.

Some proponents of the carnivore diet advocate a ‘nose-to-tail’ approach that emphasises organ meats to maximise nutrient density and compensate for some of the micronutrients that are harder to get without plant-based foods. However, many others abide religiously by the simple mantra of ‘eat meat, drink water’.

While most people tend to thrive with more bioavailable protein (hence the success for so many), there may be limitations in obtaining optimal levels of some micronutrients on a diet comprised of just red meat.

For more discussion on carnivore, see:

- The Carnivore Diet: Pros and Cons

- Optimising Dr Shawn Baker’s Carnivore Diet From First Principles

- Optimising Dr Paul Saladino’s Carnivore Diet

- Manifesto for Agnostic Nutrition

Keto

The high-fat ketogenic diet initially began as a successful treatment for children with epilepsy in the 1920s. However, after the development of drugs to treat this terrible condition, the keto diet’s popularity declined. However, keto outstripped low-carb, paleo, carnivore, and Banting combined.

Google Trends indicates that searches for ‘keto’ peaked in January 2019 and have been trending downward since then. Only time will tell if it will power on or fade out because:

- too many people encounter the limitations of ‘keto’,

- people have a limited understanding of why it works, or

- followers don’t understand how to tweak it to ensure their progress continues.

‘Keto’ means a lot of different things to the different people who have passionately embraced it and used it to describe their way of eating.

- For some, ‘keto’ means 5 per cent of total calories from carbs or less than 20 grams of carbohydrates.

- Others define ‘keto’ as any diet that produces a blood ketone level (i.e. beta-hydroxybutyrate) greater than 0.5 mmol/L.

- Still, others use keto to embrace fat as a ‘free food’ because it doesn’t elicit a significant insulin response.

This lack of clear definition means that many people identify as ‘keto’ or ‘keto-curious’ despite their fundamental beliefs about what it is and how to do it differing significantly.

When we look at the history of various iterations of lower-carb diets that have worked well for people, the things that set keto apart from others are:

- a fear of ‘excess protein’, and

- a focus on achieving higher ketone levels and flat-line blood sugars.

As you will hopefully see, these differentiations may also be the fatal flaws for the keto movement.

My Journey Through Low-Carb and Keto Land

Before keto was all the rage in 2013, I was an avid fan of Jimmy Moore’s. I followed his Livin’ La Vida Low-Carb Blog and his year-long keto weight-loss experiment. In addition, I listened to more than 1000 podcasts as he shared his journey and interviewed thought leaders of the keto universe.

I enthusiastically devoured Keto Clarity when it finally came out in August 2014 and started adding butter, cream, cheese, and MCT oil to everything in pursuit of higher ketones.

I drank Dave Asprey’s Bulletproof Coffee, believing it was the ultimate elixir of health. I even had a brief interlude with exogenous ketones.

Much of the early keto movement was built on The Art and Science of Low-Carbohydrate Living (2011) and The Art and Science of Low-Carb Performance (2012) by Dr Stephen Phinney and Dr Jeff Volek. Both Phinney and Volek contributed to the New Atkins New You(2010) with Cholesterol Clarity and Keto Clarity co-author Dr Eric Westman.

Why Keto Has Exploded (And Created So Much Division)

‘Keto’ first flourished as an underground movement rather than any government or official nutritional advice.

People following a keto diet saw themselves as rebels whose diet broke conventional rules. Now, there are seemingly endless ‘keto’ groups that each hold slightly different beliefs. This doesn’t even begin to mention the numerous books, podcasts, and conferences with differing perspectives on the subject.

Keto thrived as an alternative to processed, ‘healthy’, grain-based nutrition dogma that is not working well for us. Sadly, the spiralling healthcare costs and decreased productivity from the diabesity epidemic threaten to bankrupt us in the foreseeable future.

Keto Has Its Limits

The ‘keto’ movement would not have exploded the way it has if it didn’t prove to be beneficial for so many. There is no argument that countless people have greater satiety and better control over their blood sugars from ‘keto’ and low-carb diets.

There are plenty of critical keto reviews from ‘outsiders’ who have not lived and breathed either the diet or the community themselves. I don’t want to add to that noise.

Keto has also had its fair share of detractors from mainstream dietary circles as well as the low-fat and plant-based camps. However, this debate has likely only fuelled the growth of the keto movement because controversy gets clicks.

My aim here is not to argue the value of low-carb and keto but rather to share the insights from my journey and data analysis. I hope we can continue to evolve our understanding of how it works to adapt and evolve to help more people who desperately need it!

Any healthy, robust community needs to reflect and adapt as new insights come to light. But any group that refuses to change and becomes entrenched in dogma will not grow. Eventually, they will fade away and eventually die without refinement and adaptation.

While there are plenty of valuable insights that have been uncovered by biohackers, N=1 self-experimenters, and gurus in the low-carb and keto communities, there are also plenty of half-truths that have flourished.

While harmless in small doses, much of the keto dogma can become dangerous if taken to the extreme—especially if you follow the ‘keep calm and keto on’ mantra while ignoring the sometimes-detrimental effects.

Hopefully, this book will add some nuance to these beliefs and help you get what you need long-term.

Get your copy of Big Fat Keto Lies

I hope you’ve enjoyed this excerpt from Big Fat Keto Lies. You can get your copy of the full book here.

What the experts are saying

More

- Big Fat Keto Lies: Now On Kindle

- Big Fat Keto Lies: Introduction

- A brief history of low-carb and keto movement

- Keto Lie #1: ‘Optimal ketosis’ is a goal. More ketones are better. The lie that started the keto movement.

- Keto Lie #2: You have to be ‘in ketosis’ to burn fat

- Keto Lie #3: You should eat more fat to burn more body fat

- Keto Lie #4: Protein should be avoided due to gluconeogenesis

- Keto Lie #5: Fat is a ‘free food’ because it doesn’t elicit an insulin response

- Keto Lie #6: Food quality is not important. It’s all about reducing insulin and avoiding carbs

- Keto Lie #7: Fasting for longer is better

- Keto Lie #8: Insulin toxicity is enemy #1

- Keto Lie #9: Calories don’t count

- Keto Lie #10: Stable blood sugars will lead to fat loss

- Keto Lie #11: You should ‘eat fat to satiety’ to lose body fat

- Keto Lie #12: If in doubt, keep calm and keto on

Once again you manage to make the complex relatively simple and explanations make sense. Good reading – the book is amazing.

For me, keto seemed to only work once–I initially lost 60 lbs. (while in menopause), but then it just slowly came creeping back, even though I remained eating keto. I still eat keto to this day, but have not experienced another “miracle” like I did the first time.